Administration

Between the kaza Van and the Iranian-Ottoman border lay the kaza Mahmudiye in the far east of the province of Van. It got its name from the ruling tribal leaders of the Kurdish Mahmud clan (Kurdish: Mehmûdî), whose seat in the village of same name (Mahmudiye) was elevated to the center of the kaza in 1869.

The Mahmudiye / Hoşap / Güzelsu kaza was later integrated into the Hakkari sancak. In 1928, during republican times, the village of Mahmudiye (also Hoşap / Xoshap) was renamed Saray (‘Palace’). In 1946, the district center moved to the town of Özalp, but in 1990, Saray became the district again.

History

Even after Sultan Mahmud II (ruled 1808-1839) tried to limit the power of the Kurdish feudal lords (dere-beys, literally ‘valley princes’) in 1826, the Kurds continued to enjoy relative permissiveness in the Van region during the 19th century. In 1876, a German report on the journey of the French illustrator and painter Théophile-Louis Deyrolle to Western Armenia still correspondingly emphasised:

“The Kurds are the true masters of the country, whose Christian inhabitants (Armenians) suffer terribly from them. So it was in the year 1836, when Khan Mahmud seized the city and fortress Van, fought off all the attacks of the Turkish soldiers and then suddenly gave up his possession good-willingly. And the same conditions still prevail today, and not only in Armenia, but as far as the scourge of the Osmanli reaches at all.“[1]

Destruction

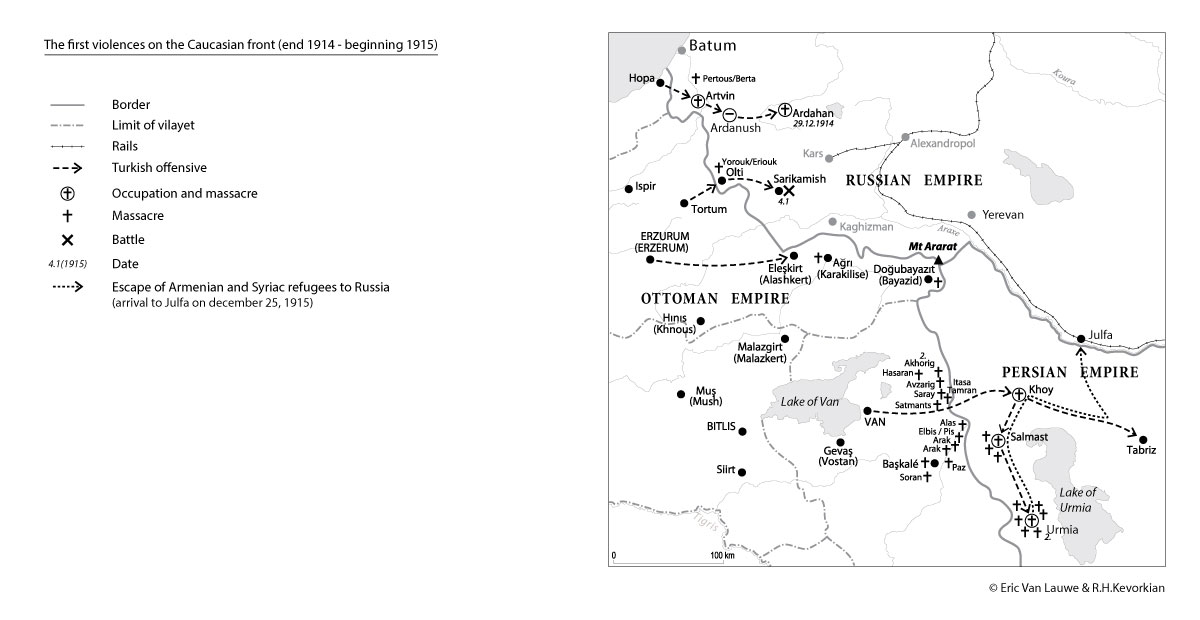

At the end of 1914 Christians in the eastern kazas Mahmudiye and Başkale were the first to suffer massacres by the irregulars of the Special Organization (Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa); among the afflicted Armenian villages whose inhabitants had been massacred in December 1914, were Akhorig, Hasan Tamran, Kharabsorek and Daşoğlu.[2] At the same time, the Ottoman Empire disposed of foreign witnesses if they were citizens of states at war with the Ottoman Empire.

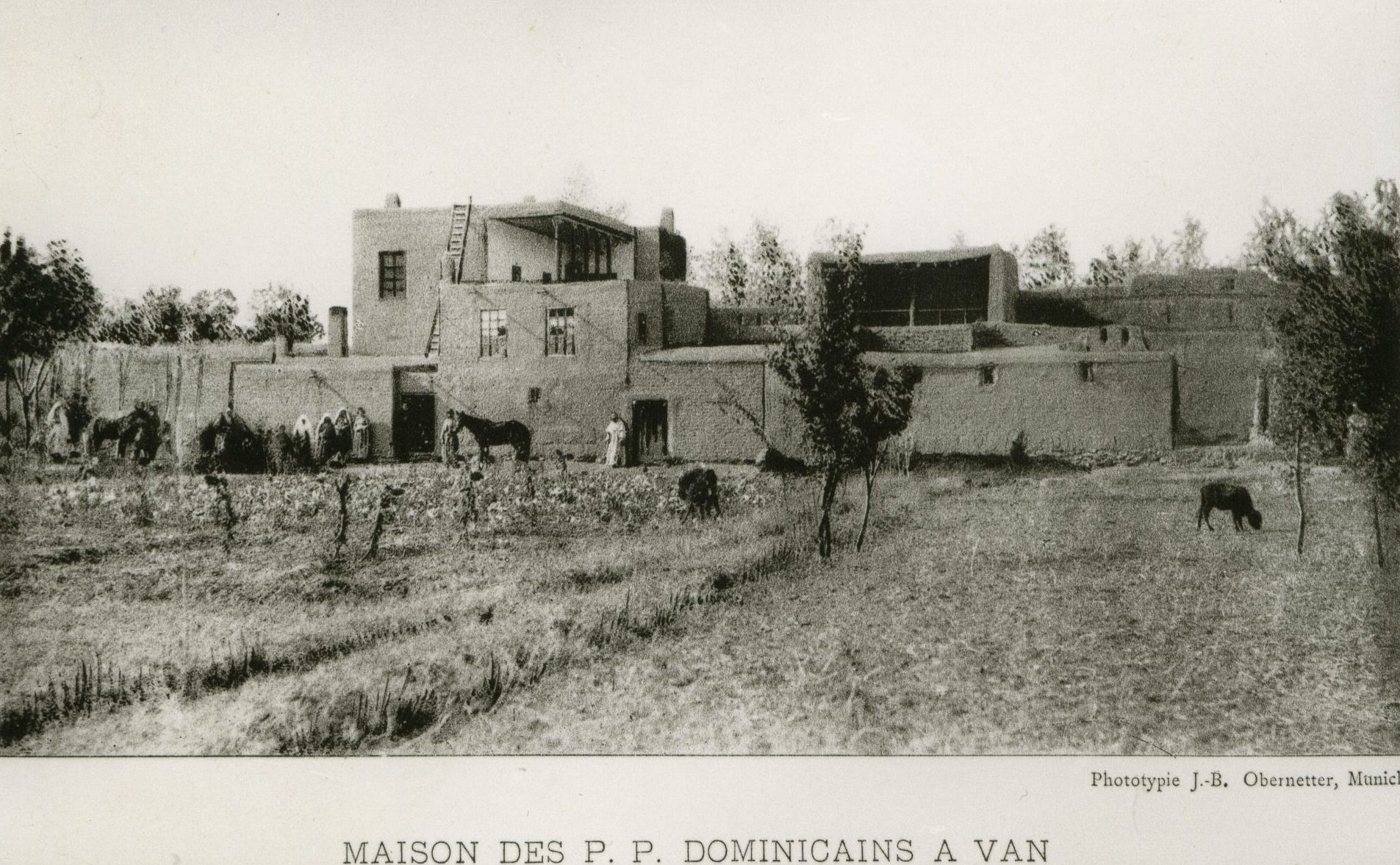

“Turkey’s entry into the war gave rise, among other significant incidents, to the 21 November 1914 expulsion of all the French missionaries from the city [Van]. The American missionaries, however, stayed on. In the same period, the first military operations led to the arrival in the city of refugees, who were fleeing the fighting or had fallen victim of the violence that çetes [irregulars] of the Special Organization had inflicted on the Armenian villages in the eastern kazas of Başkale and Mahmudiye. Those who had offered shelter to the survivors listened with consternation to their detailed descriptions of the atrocities committed by the irregulars of the Special Organization, who, they reported, killed with a ‘refined cruelty without precedent.’”[3]

Hoşap / Hoşab / Güzelsu (Town)

According to diverging etymologies of the ethnic and linguistic groups represented in the region, the toponym of the district center derives from Aramaic Xoshap or Xoşabê (‘Sunday’) or rather from the local river, which has the same Persian word ‘khoshab’ (‘fresh water’). The latter meaning is also found in the Turkish ‘güzelsu’, which has been the official place name since 1946.

The former small town of Hoşap was the headquarters of the rulers of the Kurdish Mahmudi (Mehmûdî) dynasty. In 1643, Süleyman Bey Mahmudi fortified the tribal seat with a castle.