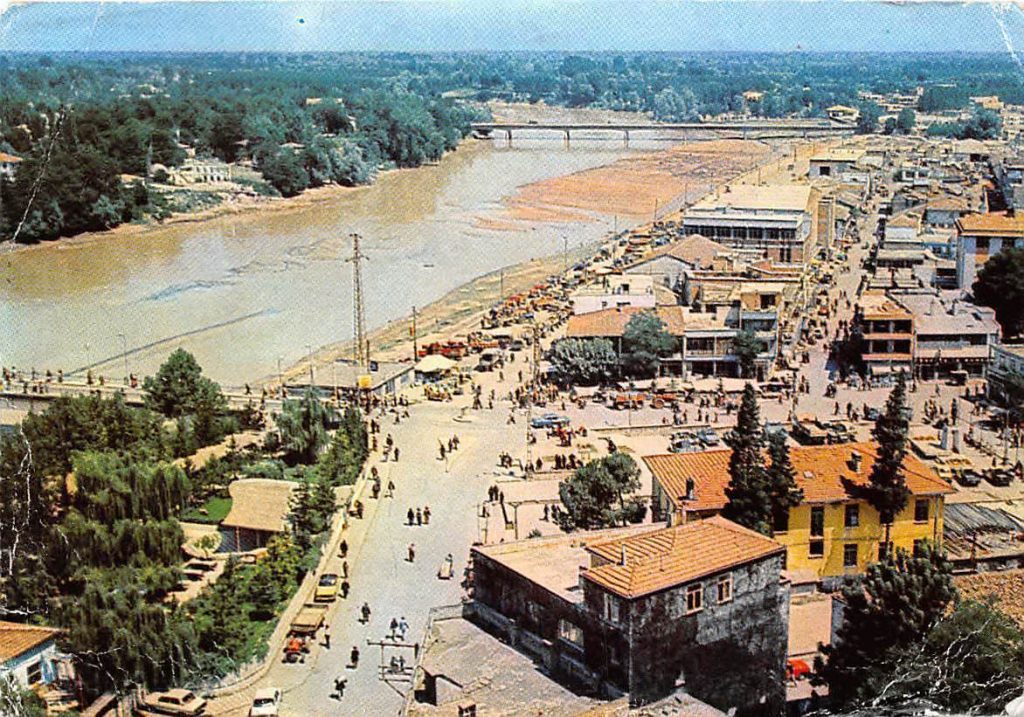

Çarşamba (Trk.: ‘Wednesday’; Grk.: Tsarsambas or Tsartsambas) is a town built on the banks of the Yeşilırmak River (Grk.: Iris river), located approximately 35km south east of Samsun, 30 km west of Terme and 45 km W-SW of Ünye.

History

Around 4,000 B.C., the area of today’s Çarşamba was first settled and at times dominated by the Hittites. In 670 B.C. the city came under the rule of the Milesians and became part of the Greek colony of Amisos (Samsun). In the 6th century B.C. the Persians occupied it and in 63 B.C. it was incorporated into the Roman Empire. In the 11th century the Turkic Seljuk conquered Çarşamba. In 1185 the Seljuk Sultan divided his empire for his eleven sons into eleven territories, whereby Rüknettin Süleyman Şah got the region in which Çarşamba is also located.

After the end of the Seljuk empire, Çarşamba became the centre of the Turkish Canik principality, which was ruled by five princes, of which Taceddinoğulları (sons of Taceddin) ruled Çarşamba and its surroundings. In 1428 it was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire. In the 17th century there was a Christian quarter west of the river. According to R. Kévorkian, the region was colonized since 1710 by Armenian peasants from the Hamshen region (Trk.: Hemşin).

Administration and Population

Around 1847 the area around Samsun was removed from the province of Sivas and incorporated into the province of Trebizond. In 1870 Çarşamba was elevated to the centre of a kaza. At that time, the city had 32,153 men or 9,200 house families (one house or apartment per family) and 119 villages.

By the end of the 19th century, there were 1,200 families living there of which 200 were Greek, 600 Muslims and 400 Armenian. The Greek population numbered 1,300, and they spoke the Pontic dialect. They supported the functioning of a 6-grade boys school, a 4-grade girls school and a church. The monastery of the Prophet Ilias was also located in the region. The town was had an important trade hub which was controlled by the Greeks and Armenians. Many of the Greeks were accomplished builders, carpenters and copper-smiths.[1]

Raymond Kévorkian summarizes the situation of the Armenian community in the town and kaza of Çarşamba: “Located four hours from the Black Sea on the banks of the Yeşil Irmak, Çarşamba had in 1914 an Armenian population of 1,800 which was settled in the western part of the town. But this district also boasted 20 Armenian villages, also founded by people from Hamşin, with a total population of 13,316 and 21 churches and 33 schools. Gurşunlu (pop. 2,800), Khapak, Ortaoymak, Erinçak, Kıyıkli, Martel, Tekvari, Takhtalik, Odiybel, Konaklik, Kapalak, Ağlac, Kabacniz, Eytidere, Olunpar, Kökceköy, Ağcagöne, Çeşmesu, Daşcığıç, and Kıstani Kırış.”[2]

Settlements inhabited by Greeks

Τμήμα Τσαρτσαμπά – Section Tsartsamba / Çarşamba

Τσαρτσαμπά – Tsartsamba (Çarşamba)

Αγατζάκινιν – Agatsakinin

Ασμάν – Asman

Γιαϊλίκερις – Yiaylikeris

Γιαγπασάν – Yiagbasan

Καμισλί κιολ – Kamislikiol

Κερπισλί – Kerpisli

Ορτούμπασι – Ortoumbasi

Πέιγενιτζε – Peiyenitse

Σαρίγιουρτ – Sariyiourt

Σιτέλ – Sitel

Τογκελούγιαταχ – Tongkelouyiatak

Τσάμαλαν – Tsamalan

Τμήμα Καζαντζιλί – Section Kazantzili

Καζαντζιλί – Kazantzili

Γιαπάνπουατζι – Yiapanpouatzi

Γοπούκ – Gopouk

Καμσί – Kamsi

Καράμπεκιρ – Karambekir

Κουζούλαγατς-κετσεγιού – Kouzoulagats-ketseyiou

Κουζουλτζάκερις – Kouzoultzakeris

Κουϊτζάκ – Kouitzak

Τανασλάρ – Tanaslar

Τενίς-τσουκουρού – Tenis-tsoukourou

Τερζέντων – Terzenton

Τσάρτσουρι – Tsartsouri

Τσινάρ – Tsinar

Χαϊντάρ – Haintar

Χιζιρλί – Hizirli[3]

The Destruction 1915-1922

As in the other kazas of the sancak Samsun, the Christian population of the region and of the kaza Çarşamba has been subjected to deportations, massacres, the annihilation of their elites and expulsion from their villages since 1915. The extermination began in 1915 with the complete deportation of the Armenians from the kaza „with the exception of a few hundred people who took refuge in the mountains under the lead of Father Kalenjian, Khachig Tulumjian, Abraham Khachadurian, and Hagopos Kehiayan.”[4]

The deportation of the Greek population followed since the end of 1916, according to a report by the Hellenic Embassy in Constantinople on 17 January 1917:

“Twenty-eight other villages [in the Samsun sancak]were burned to the ground within the week starting January 15; the villages burned in December are not included in the data. In rain and snow, women and children were marched to the Sivas and Ankara vilayets. Toddlers, little girls, women that had just given birth and women in pregnancy, as well as the sick and the elderly, are being moved from one place to another and spend the night crowded by their thousands in inns, without bread or any other food….Many children who have lost their parents are lost in the mountains or Turkish villages. The displaced die on the way due to starvation, the freezing cold, and hardship; the dead are either buried in the wilderness or left for wild animals to devour…. According to a rough estimate, the number of dead exceeds 20,000 and increases daily…. The entire male population of Bafra was moved to Boyabat…. Eight villages of Bafra, which produced the best tobacco in Turkey, were burned to ashes and their inhabitants marched to the vilavet of Ankara. Right now, smoke and fire may be seen on the mountains….The entire population of the Kerasus province have been taken to the interior regions of Anatolia….The same has happened in the provinces of Neokesaria, Fatsa and Çarşamba …. (…) One quarter of the total number of deportees have already succumbed to death.”[5]

During December 1916, the Young Turks deported Greek notables from Samsun, Bafra, Ordu, Tirebolu, Amasya, and Çarşamba and apparently hanged 200 Greeks on charges of desertion.[6]

“A postwar investigation by an American consul suggests that about 5,000 Greeks and a similar number of Armenians were eliminated from Samsun by massacre, expulsion, and flight to the hills. Samsun Turks also endured heavy losses during the war, in combat and from disease. There were also Greek deportations from the Fatsa, Nikassar, and Çarşamba areas.”[7]

In 1921 the final and main phase of the extermination of the Greek population and the remaining Armenians began: “(…) the largescale massacres and deportations began already in the spring [1921], with the rural Greek communities. In the villages of the Black Sea’s Düzce (Kurtsuyu) kaza, ‘many old men and women [were] burnt alive.’ The Turks also attacked swaths of villages around Alaçam, Bafra, and Çarşamba and in the interior as far as Havza and Vizirköpru. The Turks took pains to make sure that there were no American witnesses. Missionaries were not allowed out of Samsun, the regional missionary center. But survivors reached the town and told their stories. American naval officers reported that the campaign was ‘under strict control of the military,’ ‘directed by high authority—probably Angora,’ and carried out, at least in part, by soldiers’.”[8]

Sexualized violence, arbitrariness against and humiliation of Christian women preceded the deportation and accompanied the massacres:

“At nearby Çarşamba, the ‘good-looking women’ were ‘rounded up at night with no clothes . . . and were being held for the pleasure of the troops under Osman Ağa.’ The other women were ‘marched off’ into the interior. According to a Greek observer, Osman gathered the women and children next to the Tersakan River and slaughtered them. ‘Eighteen brides and girls selected for their beauty . . . were distributed among the chiefs of the bandits who after indulging in their beastly lust for several days shut them up in a house in [the nearby town of ] Kavza and burned them alive.’”[9]

The subsequent deportation of all Greek women and children from Çarşamba was confirmed on 30 July 1921 by an Italian resident of Samsun, Count Stanislas Schmecchia, to the commander of the US warship Overton: “He [Count Schmecchia] said that he had information from Tcharshamba [Çarşamba], that all the Greek women and children had been deported from that place and that he had further information that there was constant communication [between] certain elements in Tcharshamba and Samsoun in regard to the most favorable opportunity for an uprising and general pillage of Samsoun.”[10]

The deportation of the Greek population was supplemented by the deliberate burning of Greek villages, as observed from aboard the US warship Overton on 1 August 1921:

“Returned to ship about noon. In the afternoon, fires were noticed in the hills, and through the glasses, four or five villages were seen to be on fire. There is a report current in Samsoun, that quite [a few] of Osman Agha’s men deserted on the [way] to the front and returned to the Tcharshamba plains. The fires may be the work of this band.“[11]

The eliticide against the Pontos Greek population continued in 1921 with the death sentences by the ‘Independence Courts’. The war diary of the US warship Overton recorded the following communication received from Samsun on 18 October 1921:

“In accordance with sentence of Amassia court-martial, Commaglou Aleko, Greek of Bafra, was shot to death before the troops, having been found guilty of desertion.

‘The following Greeks of Charshamba [Çarşamba], who were members of the Pontus Committee, and who later joined the Greek bandit party in the ‘Vampire’ mountains, were captured and tried by court-martial and condemned to death:

- Baba Yirom Oglou from Kerim

- Papas Oglou from Cosma,

- Lazare Oglou from Yordan,

- Yani Oglou from Anastas,

- Sapor Oglou from Djenjek,

- Yarika Oglou from Djenjek,

- Sari Yani Oglou from Kosti.

‘The above named men, after having joined the Greek bandits in the Vampire Mountains, attacked the village of Tunkel, plundered the whole village and killed Ahmed and Mustapha. They were found guilty not only by the testimony of bona fide witnesses, but by their own confession’.”[12]