Toponym

Niksar has been identified with the ancient town Cabira or Kabeira (Grk.: τὰ Κάβειρα) of Pontos. It was also called Diospolis, Sebaste, and Neocaesaea (Neokaisareia) during the Roman period.

History

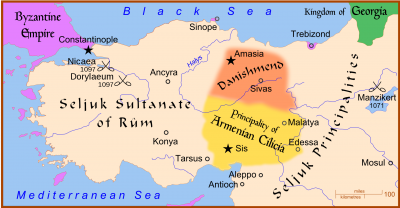

Niksar has been ruled by the Hittite, Persian, Greek, Pontic, Roman, Byzantine, Danishmend, Seljuk and Ottoman Empires.

It was known as Cabira in the Hellenistic period (Κάβειρα in Greek), being one of the favorite residences of Mithridates VI (the Great), who built a palace there, and later of King Polemon I and his successors.

In 72 or 71 B.C., the Battle of Cabira during the Third Mithridatic War took place at Cabira, and the town passed to the Romans. Pompey made it a city and gave it the name of Diopolis, while Pythodoris, widow of Polemon, made it her capital and called it Sebaste. It is not known precisely when it assumed the name of Neocaesarea, mentioned for the first time in Pliny, “Hist. Nat.”, VI, III, 1, but judging from its coins, one might suppose that it was during the reign of Tiberius. The city was completely destroyed by heavy earthquakes of 344-499, and then rebuilt. Neocaesarea became part of the Eastern Roman Empire when the Roman Empire divided into two parts in A.D. 395. It then was part of the Kingdom of Pontos, and until the 6th century was the center of Pontos Polemoniakos (64 B.C.-4th century A.D.). Under the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (527-528) it entered the province Armenia Prima.

During the Middle Ages, the Muslims and Christians disputed the possession of Neocaesarea, and in 1068 a Seljuk general, Melik-Ghazi, whose tomb is still visible, captured and pillaged it. When the Seljuks raided Anatolia in 1067, Neocaesarea was conquered by Afşın Bey, one of the commanders of Alp Arslan. The Byzantines retook the area in 1068. Conquered by Artuk Bey after the Battle of Man(t)zikert, Neocæsarea once again returned to Byzantium in 1073. Melik Gümüştekin Ahmet Gazi (better known as Danishmend Gazi), founder of the Danishmend, was the real conqueror of Neocaesarea. After the conquest the Gazi made it his capital city, and, under the name Niksar, became a center of science and culture.

By 1175, during the reign of Kılıç Arslan II, Niksar was dependent on the Seljuks of Rum. After the Mongol invasion of the 13th century, Niksar was governed by the Eretnids and then the Beylik of Tacettin, and became the center of the latter principality. After Kadı Burhanettin (who conquered Niksar in 1387) was killed in battle, the people of Niksar sought aid from the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I. The Sultan’s son, Süleyman Çelebi, took Niksar for the Ottomans. Fatih Mehmet launched a raid on Trabzon from Niksar, and Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent raided the east from there. The town was predominantly Muslim in the mid-17th century.

Ecclesiastical history

Neocaesarea was an episcopal see in the late Roman province of Pontus Polemoniacus. At first called Cabira, it became the civil and religious metropolis of Pontus. In around 315, the Synod of Neo-Caesarea was held there. It is now one of the bishoprics listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees and is referred to as Neocaesarea in Pontos to distinguish it from Neocaesarea in Syria.

Christian Population

In the beginning of the 20th ntury, the kaza’s overall population was 28,576, consisting of Muslims (Turks), Armenians, and Greeks.[1] The population cultivated grains (wheat, barley, rice, oats), olives. fig and grapes and were engaged in cattle breeding, also exploiting the copper ore mines in the Niksar area. Armenians were engaged in agriculture, handicrafts and trade. The city mainly sold wheat, barley, tobacco, hashish and other handicrafts.

The city of Niksar had an Armenian church (Surb Astvatsatsin) and the Greek Orthodox church of Holy Nicholas.[2]

“Of the 3,560 Armenians in the kaza of Niksar, 2,830 lived in the principal town, also called Niksar. Known in antiquity as Neocaesarea, Niksar lay 53 kilometers northwest of Tokat in the fertile plain of the Kelkit Çay [(Armenian: Գայլ գետ ‘wolf river’; Grk.: Λύκος – Lykos, ‘wolf]. Almost all Armenians here were Turkish-speaking and, with a few exceptions, earned a living as craftsmen, businessmen, or farmers. The 8 June 1896 massacres ruined the community, whose property was systematically pillaged; thereafter, the Armenians failed to recover the prosperity that they had enjoyed in the past.

There were also two Armenian villages in the kaza: Kapuağzi (with an Armenian-speaking population of 650) and Karameşe (pop. 80).”[3]

Until the 1930s there lived up to 300 Armenians in Niksar.[4]

Based on a 1911 survey Greek villages in Pontos, Ioannis Sianloglou gave in 1923 the number of Greek in the Niksar kaza with 24,100, residing in 57 localities with 50 schools, and 55 churches.[5]

List of Greek settlements in the kaza Niksar / Neocaesarea

Νεοκαισάρεια – Neocaesarea (Niksar)

Αργοσλού – Argoslou

Ασάρ – Asar

Ασαρτζούχ – Asartsoukh

Γένιτζε – Yenitze

Έντιρεκ – Entirek

Έργιαπα – Eryiapa

Ερέστιζι – Erestizi

Ιραβάν – Iravan

Καράογλαν – Karaoglan

Καράσουλεϊμαν – Karasouleyman

Κετενλίκ – Ketenlik

Κιλαβούζ – Kilavouz

Κιλίγερις – Kiliyeris

Ιλεγέν – Ileyen

Σορχούν – Sorkhoun

Σουλούγκιόλ – Soulougkiol (Sulugkyöl)

Σουλτούκ – Soultouk

Ταχταλί – Takhtali

Τεπέ – Tepe

Φελ – Fel

Χάνγιερι – Hanyieri

Χασάνκιοϊ – Hasankioy (Hasanköy)

Χατζαμπετίνογλουτσιφλίκ – Hatzambetinogloutsiflik (Hacambetinoğluçiftlik)[6]

Destruction

Armenians

In the kaza of Niksar the execution of men and the deportation of the remaining population—some 3,500 people—take place at the end of June 1915 under the direction of the kaymakam, Rahmi Bey[7], “who held his post from 4 May 1914 to 8 August 1915.”[8]

Greeks

“In October 1916, a brigade was sent against the Inoi/Ünye area, supposedly to capture guerrillas. Ioakeim Saltsis notes that in the course of those events, after the Ottoman brigadier had the notables of eleven Greek villages arrested as hostages, he moved on to the area of Keris. One of those villages belonged to the estate of Nikolaos Yeleklidis, a merchant and land-owner of Inoi/Ünye and a notable of the community. Due to the lie of the land, the guerrillas decided to make a stand there. The ensuing battle which lasted 24 hours, the brigade, trained their artillery on the guerrillas. When the guerrillas ran out of ammunition, they managed to escape. N. Yeleklidis and his son Yiorgos were brought before a court-marshal, but were found innocent. Nonetheless, they were executed on the demand of the Turkish landlords and military commanders of Inoi. Another 520 villagers in the area who had also been taken as hostages were massacred along with them. As a conclusion to these events, all eleven villages were burned to the ground and the women, children and elderly of Neokesaria (Niksar), Tokat and Amasya were displaced, meaning that they were subjected to ‘white slaughter.’”[9]

The Black Book (1919) of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople quantifies the number of Greek Orthodox Christians deported from the “Neocaesarea region” during WW1 at 27,216.[10]

On 20 May 1919, Archimandrite Panaretos and Dr. K.A. Fotiadis, commissioned by the Central Pontian Union of Greeks of Ekaterinodar and a special recommendation from the Patriarch, visited the ecclesiastical regions of Pontos and recorded the picture in detail, including the ‘province of Neokesaria’ (Niksar), “which includes ten administrative regions of the Prefecture of Trebizond, the independent administration of Samsun, the Prefecture of Sivas and the Prefecture of Kastamoni, had [before the?] war 14 cities, 166 villages, one high school, 18 middle- schools, 173 schools and a total of 97,450 residents of Greek extraction. 25,000 were relocated or exiled—especially those along the coast—to the hinterland of Asia Minor. In August 1917 alone, 2,700 of the residents of Ordu were abducted by the Russian Army and taken to Russia. Of the 25,000 exiles, from the villages on the one hand, only 6% of those from villages were saved from the catastrophe dealt by the satanic Turkish savagery, along with only 35% from the towns. Twenty priests from the province were shot, hanged, burnt or buried alive. Ordu presented an image of unimagined destruction; 9/10 of Greek homes have been razed to the ground, while the plots are used by the Turks to plant cabbages.”[11]

Persecutions, massacres and deportations were continued by the Kemalist regime since May 1919.

“Apart from the district of Kerasus [Giresun], the districts that suffered the most from Osman’s irregulars were those of Neokesaria (Niksar) and Samsun. He personally saw to ‘the total devastation of 37 Greek villages in this territory, including the extermination of women and children. In most of the villages, women and children were subjected to a literal holocaust; they were herded into schools or churches and barricaded with dry grass, which was then set on fire. Of the villages that had been burned to the ground, the most noteworthy are: Ahancık, Inere, Kayacık, Kayatepe, Tepeköy, Gusova, Haydar, and Idala.

In the exclusively Greek village of Peyala and under the pretext of a survey concerning the population of women and children, as the men had already been sent into exile, he gathered all the children and toddlers in the school and nearby church, placed dry grass on the roofs and all around, and set them on fire.

It is said that the smell of burning flesh, the heartrending cries and the agony of the victims touched a few of the culprits, who turned away and left the horrible scene, though Osman Ağa continued to roar in satisfaction at this unsurpassable pleasure.’”[12]

According to the data of the ecclesiastical districts and Greek Orthodox communities, by 1 December 1922, the number of victims in in the Metropolitan Ecclestical district of Neokaisarea (Niksar) – not to be confused with the kaza of Niksar – were 27,216 in 95 communities that had been completely destroyed, including 135 looted and burnt churches and 106 schools.[13]

In May 1922 slaughters in the western part of Pontos continued, including Niksar.[14]