Armenian Population

“In the plain of Mush, the Armenians are in a large majority, the official figures for the caza allowing them a total of 35,300, as against 21,250 Mussulmans. Some 2,500 of their number are Catholics, and about 500 Protestants.”[1]

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople there lived 75,623 Armenians in 103 localities of the kaza Mush, maintaining 113 churches, 74 monasteries, and 87 schools for 3,057 students.[2]

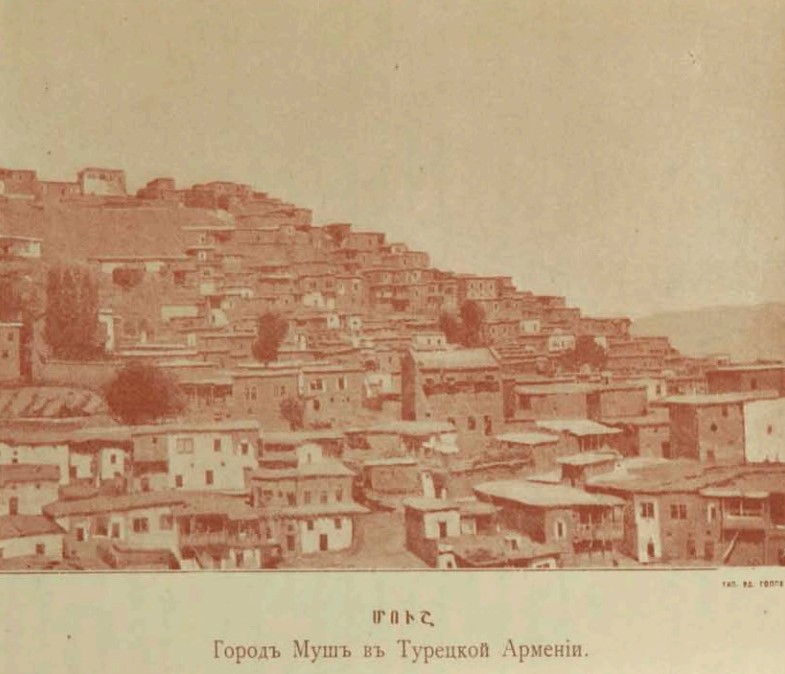

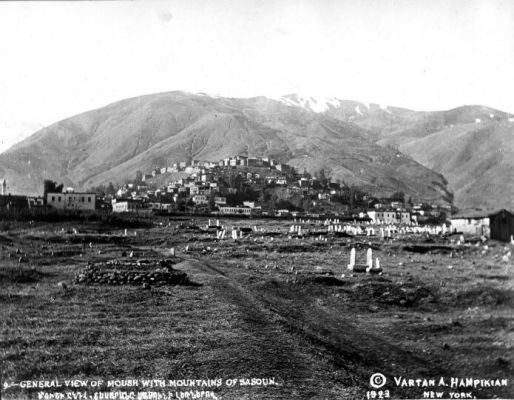

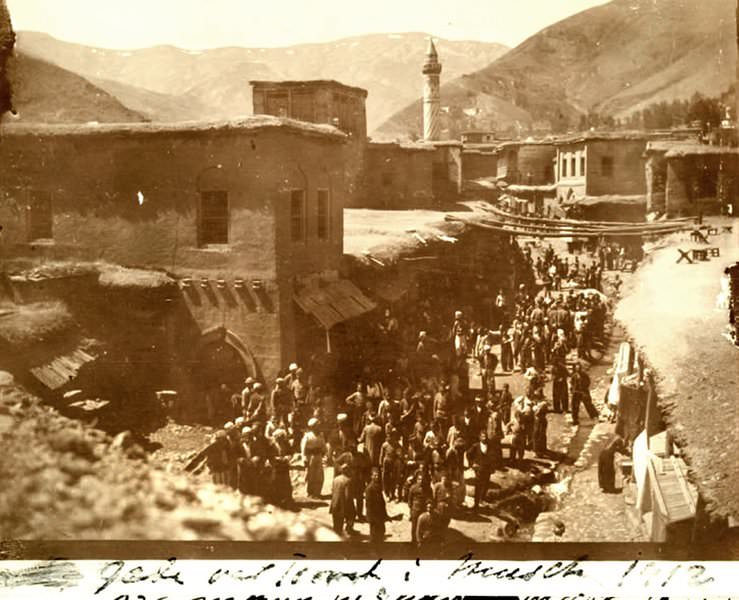

City of Muş / Մուշ – Mush

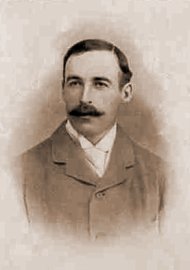

Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch: “…the most Mis-Governed Town in the Ottoman Empire”

Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch: “…the most Mis-Governed Town in the Ottoman Empire”

“Mush is the most mis-governed town in the Ottoman Empire. Ever since the inauguration of closer relations between Europe and these countries, the testimony of the few Europeans who have realized and noted such facts bears out this judgment almost to the letter. It is less easy to assign any definite cause. The disease has become chronic; and its symptoms are so familiar that the inhabitants have grown callous to their condition. (…)

The Mussulman majority are probably almost all of Kurdish origin; and since the enrolment of the Hamidiyeh irregular cavalry they openly profess the name of Kurd. The slopes of the hills around Mush are covered with vineyards and gardens; and in each garden there is a small, two-storeyed house, resembling from a distance a scattering of bathing-machines. The Mussulman retire to these gardens during summer, and superintend their cultivation. The whole winter through they sit idle in Mush. There they consume a great quantity of tobacco; and all this tobacco is contraband. It is their custom to buy wives, the best-looking and best-born women sometimes fetching not less than a hundred pounds. All are obstinate in their belief that it was the Prussians who enabled the Russians to conquer Turkey in the last war. Their hope is that this assistance will not be forthcoming in the future, and that they are therefore confident of success in the conflict they foresee. And they pit their Hamidiyeh against the Cossacks.

The Armenian minority are artisans, smiths, makers of everything that is manufactured in Mush. They are carpenters, plasterers, builders. All the keepers of booths which we passed in the bazar plainly belonged to that race.(…)

At present day [Mush] contains two considerable mosques with minarets, four churches of the Gregorian Armenians and one of the Catholics. The Gregorian churches are named Surb Marineh, Surb Kirakos, Surb Avetaranotz, and Surb Stepanos. None are of any size or of much interest.”

Excerpted from: Lynch, H.F.B.: Armenia: Travels and Studies. Vol. Two: The Turkish Provinces. (Reprint). Beirut: Khayats, Third edition, 1990, p. 172 f.

Population

H.F.B. Lynch wrote that he was “unable to supply any reliable statistics for the town itself; but my impression was that the population was certainly less than 20,000 souls. In the cloister of Surb Karapet it was believed that Mush contained nearly 7000 houses, of which 5000 were occupied by Mussulmans and 1800 by Armenian families. Although this estimate is certainly too high, it would appear that the population has been increasing. In 1838 Consul Brant speaks of 700 Mussulman families and 500 Armenians, which would give a total of not more than some 6000 or 7000 souls. Thirty years later, Consul Taylor, who visited the place, computed the inhabitants of Mush and the vicinity, not including the plain, as numbering 13,000 souls, 6000 Armenians and the rest Mussulmans.”[3]

“On the eve of World War I, there were about 20,000 inhabitants in the town of Mush, divided into distinct Armenian and Muslim quarters with a mixed central business district having some 800 Armenian shops and workplaces. The Armenian craftsmen were particularly noted as shoemakers, tailors, painters, smiths, jewelers, and pottery makers. The town had five active Armenian churches and parochial schools, aside from the noted Izmirlian School for girls and the highly-regarded academy sponsored by the United Association of Constantinople.”[4]

The Swedish missionary Alma Johansson estimated the Armenian population of Mush at 25,000 in 1915.

Two Scandinavian witnesses in Mush

Norwegian sister Bodil Katharine Biørn (1871-1960) and the Swedish missionary Alma Johansson (1880-1974) were the only Western eyewitnesses to the massacres in the town of Mush and its surroundings.

Biørn (‘Mother Katharine’) came from a wealthy family and was one of eleven siblings. After leaving school, she wanted to become a concert singer, but at the age of 25 increasingly turned to religion instead, and for this reason wanted to help suffering people. She trained as a nurse in Norway and Germany. The organization Kvinnelige Misjonsarbeidere (KMA) sent her as a missionary to the east of the Ottoman Empire in 1905, after she had attended a mission school in Copenhagen in 1904. Initially, she worked in Mezereh (now Elazığ).

In Muş, she ran a hospital and a children’s home for Armenians from 1907. She received between 50 and 70 patients there daily. During the genocide, patients and staff at the hospital were murdered or expelled. After the genocide, she returned to Norway in 1917. In 1921, she moved to Armenia and opened a children’s home in Alexandropol (now Gyumri) with Norwegian donations. After Armenia’s annexation to the Soviet Union, she had to leave the country in 1924.

She went to Aleppo in Syria and worked with Armenian refugees there. In 1934, she traveled back to Norway. Until her death, she dedicated herself to the fate of Armenian genocide survivors and refugees with fundraising, lectures, and articles.

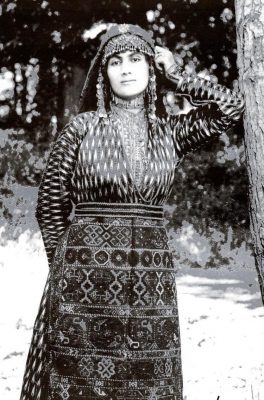

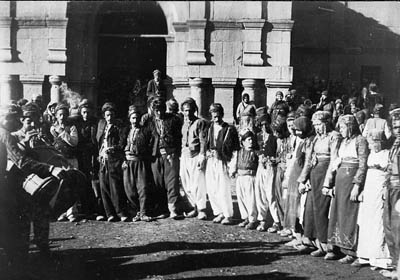

Bodil Biørn’s photograph collection

(…) “Biørn and her KMA colleagues recorded their work with the use of photography and texts capturing moments of this period, from the early 1900s to the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide. (…)

The KMA work in the Ottoman Empire began in 1901 when missionaries travelled to take care of the orphan children left from the large-scale massacres of Armenians in 1894–96. (…)

Documentation before 1915

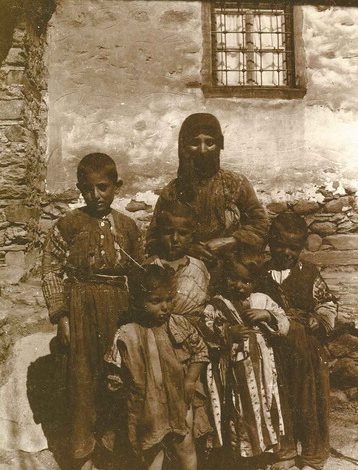

With the aid of her personal camera, Biørn documented her work with the local community, the places she visited, the people she met, and her life in general. Biørn’s photographs are initially compiled in photographic diaries, where she writes the name of the people she is photographing, the places, the date and in many cases the context. The photographs cover a spectrum of images that fall into categories: landscapes, buildings, groups of people she meets on the road, families working for the mission stations or attached to one of the KMA units of care (orphanage, school or health centre), the orphans, the widows, the starvation. Most of the photographs are of people, both adults and children. These images can be classified as portraits, as they mostly depict the people posing for the photographs. A small number portray starving children lying on the streets of Mush or standing looking at the camera.

Biørn’s photographs served the purpose of raising funds abroad, similar to the contemporary use of photographs in charities and non-governmental organizations. Biørn would take portraits of the children in extreme poverty which would then be printed on pamphlets describing the destitution, the work that was needed and the work that was being done. Biørn would then capture the improvements made with the funds raised. Alongside the photographs, the missionaries wrote letters about their daily lives which were published in the organization’s international newsletter Kvartalshilsen.

The nature of all these documents, photos and correspondence, changed during Biørn’s stay in Mush. Whilst at first they were for recording destitution, raising funds, and disseminating the results of the Mission’s work, in 1915 they became a way to record the victims of genocide and inform the outside world.

The Genocide

(…) In 1915, Biørn was running Deutsche Hülfsbund’s policlinic in Mush, which was an orphanage for boys and a day-school for girls. All foreigners were told to leave the area before the killings began. Yet Biørn and her colleague Alma Johansson stayed, as Biørn had caught typhoid fever and was bedridden. Biørn witnessed the arrests, deportation and massacring of Armenians at the hands of the Turkish authorities.

Biørn attempted to corroborate the atrocities by using her photographs as a medium through which to show who the victims were. The pictures taken during her years working and living in Mush were copied (presumably by Biørn herself), and a new text was added with the names of the people, dates and their eventual deaths. Whilst an entry in her diary before 1915 described the people in the photograph as ‘The widow Heghin with her 5 sons’, an unpasted copy of the same photograph was later amended to add ‘Heghin with her 5 sons, two were received in our orphanage. They were burnt in their house during the murders in Mush in 1915. She helped us in the orphanage with her son. She was a good woman of faith.’

(…) The entire collection has been digitalized and can be found both on the Riksarkivet website and Wikimedia Norge which have published the photographs along with the text. The texts at the back of the photographs or written on the pages of the albums or diaries are short and descriptive, never claiming to speak for the victims, yet humanizing them by informing us of their identity and calling attention to an atrocity. The photographs depict the extermination of people through starvation and deprivation, as well as the faces of future victims ‘returning the gaze’, in their daily routines or posing for a picture. (…)

After Biørn’s death in 1960, the use of these records ended as they became buried in the KMA archive. When the KMA dissolved in 1983, their archive was offered as a gift to Riksarkivet. It included 1379 photographs, many taken by Biørn, Biørn’s personal photo album and diary, the correspondence of missionaries from around the world to the organization’s newsletter, loose photographs, slides, the fundraising pamphlets and the organization’s account book. It is difficult to know how ‘complete’ the collection is, how many photographs were kept privately by Biørn or how many were damaged or destroyed.

Riksarkivet

Between 1983 and 2005 Riksarkivet arranged and catalogued this material, yet the result of this cataloguing meant ‘no one knew what the fonds contained’. The archival description had not mentioned the Armenian Genocide, concentrating instead on the institutional creator, the KMA. The little knowledge at Riksarkivet about what lay behind this material meant little to no use of them before 2005.

In early 2000s, a senior archivist at Riksarkivet received a telephone call from Biørn’s grandson inquiring whether the archive had documents pertaining to his grandmother. The query led the archivist to the KMA archive. Sometime later, the same archivist heard a radio interview where a man described his grandmother’s work as a nurse in the Ottoman Empire during the first decades of 1900. There, his grandmother adopted an Armenian orphan boy who was to become the father of the man being interviewed. The impression the interview left on the archivist prompted him to investigate further. It was at this point Biørn’s photographs were ‘discovered’.

This led to a more detailed arrangement and cataloguing of the records and an online exhibition a year later in 2005 called ‘Norwegian Women Document Genocide’. The exhibition, published in both English and Norwegian, consisted of photographs taken by Biørn and other anonymous sources, of the places and people affected by the Armenian Genocide. It included a photograph of an Armenian refugee camp in Aleppo, Syria, a photograph of the founders of the KMA, photos of the missionaries at work, including Biørn, but mainly the photographs were of the Armenian population in Mush with the text that Biørn wrote after the Genocide. (…)

The exhibition was put together through a process of selection, to tell a story. Due to the nature of the documents the archive had, it was the story of the missionaries, not the victims. The story of the missionaries however led to the larger story of the Armenian Genocide and the possibility of acknowledging the victims. This was significant because the Norwegian government at that time (and to this day) has not acknowledged the 1915 events as genocide. (…)

Excerpted from: Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup (2020): Documenting the Armenian Genocide in Norway: the role of a National Archive in the social life of a collection, Archives and Records, DOI: 10.1080/23257962.2020.1813094

Alma Johansson: “I can never forget the sight. And nothing could you do for them!”

In 1901, the Missionary Society of Swedish Women sent Johansson to Mush (Western Armenia), where she stayed until December, 1915. She worked at a German orphanage for Armenian children, which was under the direction of the German relief organization Hilfsbund für Christliches Liebeswerk im Orient. She wrote about her experiences in a book called Ett folk i landsflykt: Ett år ur armeniernas historia (“A People in Exile: One Year in the Life of the Armenians”, Stockholm: Kvinnliga missions arbetare, 1930), both of which were translated into Armenian and French.

She also made testimonies to German and American diplomats who published them later. Alma told about how women took poison so they wouldn’t be captured by the Turks, and how the soldiers transported bloody, wounded women and children through the city while other soldiers fired at them just to frighten. When the wounded fell to the ground, the soldiers would hit them with the butt ends of their rifles.

She gave information about how the kids at the orphanage were handed over to a Turkish officer, and then taken to a building outside the city where they all were murdered.

In 1923 Johansson moved to Salonika, and established a factory for more than 200 Armenian refugee women. She also founded an Armenian kindergarten and primary school in Charilaos (Greece).

Alma Johansson’s Report on the Mush Massacres, July 1915

On 22 November 1915, the head of the German charity NGO Hilfsbund für Christliches Liebeswerk im Orient, Friedrich Schuchardt, sent Alma Johansson’s report on her experiences in Mush to the German Foreign Office and the German ambassador at Constantinople:

From the director of the German Christian Charity-Organisation for the Orient Friedrich Schuchardt to Rosenberg, Legation Councillor in the Foreign Office

Privat Correspondence

Constantinople, 22 November 1915

Dear Privy Legation Councillor,

I have filed a copy of the enclosed reports sent by the Imperial Embassy to Consul General Mordtmann.

Yours sincerely,

Respectfully,

F. Schuchardt

Enclosure 1

The Massacres in Armenia 1915

Those outsiders who hear of the terrible atrocities carried out against the Armenians during the past few months cannot believe the reports at first. Then, the question arises, “How did this ever happen?”

Those of us in the country’s interior saw the situation develop step by step. (Naturally, I can only speak for the provinces in the interior, where we saw everything happen.)

The systematic robbing of the Armenians already started when the mobilization began. Not only those items were taken which might be needed for the war, but everything which was of any value at all. Any Turk could enter a shop or a house and take whatever he wanted.

Now, it is true that the fundamental attitude of the Armenians was quite the opposite of being pro-German, but they were not pro-Russian, either, nor did they hope for anything from the British. With a satanic sort of cleverness, the Turks knew how to stir up this opinion of the Armenians against Germany, naturally in order to be able to deliver proof afterwards. For example, the most unbelievable stories were spread among the Armenians about us two sisters to make them thoroughly hate us.

Since the war began then, everyone among the Armenians who was of an age to serve was called up, whether sick, blind or a cripple, with the exception of those who had been exempted. And yet, until the very end, the strongest people among the Turks escaped this fate either through friendship or bribery.

Then the food needed had to be brought to the Russian border, but who was to do this? There were only the Armenians, and since the government had taken away their animals for other purposes, they had to carry the loads on their backs. Now, the winters in the Mush-Erzurum region are very long and harsh, and the people often needed 2 – 3 weeks to reach their place of destination. The people were not dressed for this, as they had no money to do so, and anyone with anything on them had it taken away from the gendarmes accompanying them. Masses of these bearers, made up of children, old people and those who had been extempted, died along the way due to the cold and deprivation. Whenever anyone fell down from weakness, he was beaten by the gendarmes riding with them until he either attempted to walk again or fell down dead. Another freezing comrade then took the few clothes off the dead man in order to protect himself somewhat from the cold. It was a good thing if a third or even a quarter of each crowd which left Mush returned alive. Although Kurds were also used as bearers, they always ran away. And it can hardly be considered a great sin if the Armenians, at least those who could, gradually attempted to escape.

Then there were the stories of the gendarmes in the villages. Bad people who were unemployed allowed themselves to be signed up as gendarmes in the town and the surrounding area; these people were given unlimited rights to rob, for the government had said, woe to anyone who refused the gendarmes or soldiers. Taken on its own, all the things that happened there became a long, dark history of violence and inhumanity. The Armenians only defended themselves a few times in order to protect the women from the violence of the Turks, as a result of which a village would be burned down in part or entirely. Because the “Holy War” had been proclaimed, we knew what this would lead to. Rousing speeches were made that, “because we are fighting a war against the Christians, we must first annihilate the Christians in our country”. And they all counted on the Russians coming at least as far as Mush, but it was said that before this happened, they would first slaughter the Armenians, and then the Russians could come. In November 1914, it was officially admitted that they were only waiting for a reason for a massacre and as soon as they found one, they would not leave even one Armenian alive.

The winter passed in this manner, and every day we thought that the misery could get no worse. In March we heard of unrest in Van, but we hoped that the rumors were exaggerated. But gradually both Armenian as well as Turkish reports came through, and strangely they backed one another up, except that the Turkish reports went even further. Officers and public officials proudly told us that the Armenians in Van were now annihilated, “everything hacked, hacked up into little bits”. (The Russians only arrived a few weeks later in Van.)

At the beginning of May we heard of massacres in Bitlis, and everything had been prepared for a massacre in Mush. Then the Russians arrived in Lies [Lice?] (16 hours from Mush) and that is what saved Mush this time, for now all of the attention was there, but things became more frightening every day. Any Armenian who held any sort of position with the government was removed from office and quietly eliminated. From now on, all of the bearers were also killed every time they arrived at the front with the provisions, although certainly one or several almost always managed to escape. During that time, the entire stretch behind the front from Erzurum to Lake Van was destroyed by the soldiers; here and there, women who had escaped arrived in Mush with their children, but I cannot describe the state they were in and the stories they told.

In the middle of June, Servet Bey, the Mutessarif and an intimate friend of Enver Pasha, had both of us sisters called to him and said that we had to travel to Mamuret-ul-Aziz in a few days’ time. The German and Turkish governments in Constantinople had decided that all foreigners were to be sent there. We requested that he leave us where we were, but he became very outraged and screamed at us that, if we did not go willingly, he would send us by force, “I have the right to do so.” He also said we could take our employees with us, but he answered our question as to whether there was no danger for them, “Nothing will happen to you; only when they see an Armenian do they cut off his head.”

We were told in a friendly way from other sides that we should not go; bad things had been planned for us along the way. In June, many military convoys passed through Mush and all of them, both officers and soldiers, spoke very heatedly in the marketplace about the fact that Armenians were still alive in Mush.

Fierce shooting began on the evening of 10 July and lasted for a few hours. The next morning, the whole town was in arms. Naturally, no Armenian dared to leave his home. I then went to the Mutessarif and requested that he ensure the safety of our homes. He was very angry and said it served us right; why hadn’t we left? Now there was nothing he could do for us. The entire town had been besieged for weeks; 11 canons had been set up around it. Apart from those soldiers already there, 20,000 extra soldiers came to Mush.

The Mutessarif advised us to move to a Turkish quarter (for our houses were in the centre of town). But how could we move when Sister Bodil was very ill with typhoid fever? I asked for a few men to help us and an ox cart for the sick sister, but he could not give us that. And so we had to remain where we were. The Mutessarif had had a visit at noon from the richest Armenians and told them that the entire population would have to leave Mush in 3 days’ time. They were allowed to leave their families there if they wished, but whether or not they took them along or left them: everything they owned belonged to the government. Now, those rich people who still had some money went along with this; they thought that in this way they would at least escape with their lives. But the other Armenians (not many men were still alive) said that such conditions only meant certain death and so they decided they would rather die together in their houses, and only if the soldiers attempted to enter with force would they sell their lives as dearly as possible. As I have mentioned, they had been given 3 days, but after a few hours the soldiers began to enter the houses around us by force. From our house we could see and hear many things. Several women with their children as well as some of our married girls fled to our house.

Early the following morning, 12 July, we heard some rifle shots and then the canons immediately started to fire. Now, I am sure I do not need to describe the bombardment of a town. Apart from the soldiers, all of the Turks from Mush had weapons, and they distributed themselves among the soldiers, because they knew where game was to be caught. Here and there, firing was returned from the houses as a last defence. Fires soon broke out on every corner. The first crowd of women and children who had been collected marched past our house on the second morning. I am not yet able to describe the images, bloody, crying … The outer gate of the orphanage was already smashed on the first day. They demanded that I open the gate as they were searching for refugees. Some of our village teachers, who had come to us on the previous day and could not leave because of the sudden shooting in the morning, were taken away. During these proceedings, some girls and a woman who were standing next to me were shot dead.

On the third day, several officers and a troop of soldiers came again with a written order from the Mutessarif that everyone who was in our houses had to be handed over, and the entire people would be sent to Urfa. Together with the male servants, only three girls were allowed to stay with us as servants. Despite the heavy shooting, I then climbed up to the Mutessarif. He was standing next to a canon as the supreme commander. All my begging and pleading was of no use; the houses were emptied. Asraf Bey [Mordtmann in document 1915-11-06-DE-012 called him ‘Assat Bey’], a doctor, acted particularly dreadfully. He almost shot me in the house, and I had to ask the captain several times to look after the doctor, as otherwise he would already have shot people in the garden. But if I had known that the children and women were only led away to die, I believe I would have chanced all of us being killed together in the house. But I was given a word of honour and assured that they would be taken safely to Urfa. We received the first piece of terrible news on the evening of the same day. A few bakers, who were needed by the government, heard everything, for it was reported loudly in the market.

After everyone had left our houses, two gendarmes were assigned to protect us. They told us all the same shocking stories. The men who were caught alive (but there were only a few) were immediately shot just outside the town. The women were taken with the children to the next villages, locked by the hundreds into houses and burned. Others were thrown into the river. Yes, even higher officers always came to visit us now and they proudly told the same stories. This much is true: except for a small number of women who the Kurds or the Turks took for themselves, almost everything in the entire Mush region which could call itself Armenian has been exterminated, and no one got beyond the district.

The shooting lasted for an entire week, the canons only for three days. And it was particularly bad at night: all around us, the neighbours could shoot through the windows into our houses. The walls were also pierced with bullets. Often we did not know where to hide. We could barely stand the smell from the corpses, but also from the many bodies lying burned in the houses. Here and there, the dogs tugged and pulled at the corpses. There had been about 25,000 Armenians in Mush; in addition, Mush has 300 villages, most of which had been Armenian. When we left Mush after three weeks, everything was burned down. Everywhere along the road where we met Kurds we were told the same stories. And the many corpses along the road! But those were only individuals; the female corpses were all naked.

Then we arrived in Mamuret-ul-Aziz. All of the orphanages there were full, including several teachers, but that was all we found. (…)

I left Mezeré at the beginning of October. The piles of corpses along the way! I could hardly bear it. We also met several crowds of women and children; they were a miserable sight. The gendarmes riding with them spoke openly of what they did to the poor people along the way. When asked, “Where are they going?” they answered, “If no one else will take them and they don’t die, then we’ll just have to kill them.”

A great many women and girls were taken by the Turks and Kurds, especially in Harput and Mezeré; the husbands of many of these women are in the United States.

One can say that, as a people, the Armenians are finished; several thousand should still be alive. Should they also perish?

Alma Johansson

Source: http://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs/1915-11-22-DE-001

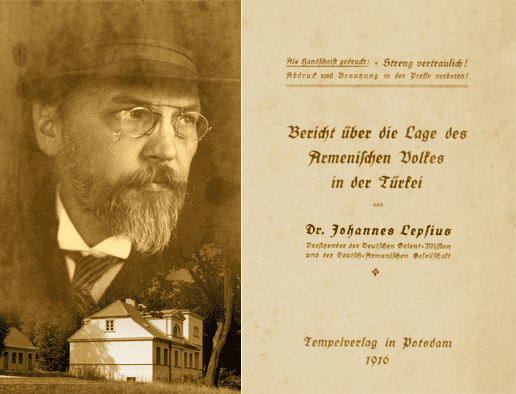

Johannes Lepsius: The Massacre in Mush

On the morning of 3 July, the slaughter in Mush began. The cannons were directed against the upper part of the town, so that the houses there collapsed and a conflagration broke out. The Armenians left the houses and fled to another part of the town, some of them being massacred in the streets. The upper part of the town was completely destroyed. Now the attack was directed against the ‘Brut’ district. The Armenians were crowded there and saw their female relatives violated and their brothers killed. After the destruction of this district as well, the attacks turned to the ‘Smareni’ district. There, unspeakable atrocities were committed. Since there was no rescue, the Armenians tried to kill themselves. Thus, Tigran Zinoian gathered all the members of his family in Mush, 70 people, and handed poison to all of them. After they succumbed to the poison, he set fire to the house and shot himself.

Other families burned their houses to perish in the flames, many shot their wives and children to save them from defilement and Islamization.

Haci Hagop fell during a raid, but his companions continued to defend the town. In the meantime, all parts of the city except ‘Zor’ were destroyed, and the remaining part of the Armenian population was crowded in this part located at the far end of the town, about 10 to 12,000 people.

The 4th of July came. The bombardment and the attacks of the Kurdish hordes increased to their greatest ferocity. But the few Armenian defenders also doubled their resistance and shot hundreds of Kurds. But what did this mean? The houses of Zor were gradually shot into ruins and all the Armenians who were still alive decided to cross the river bordering Zor the following night and flee to the mountains of Goghu Glukh in the hope of reaching Sasun. At the eleventh hour of the evening, the masses started moving towards the river. But the burning houses illuminated the area at a distance of 8-10 kilometers. They were noticed by their pursuers and fired upon. Many fell victim to bullets, others to the crush, and still others to the waves, and only 5-6,000 reached the other bank and fled into the mountains.

The Kurds then gathered the wounded and any Armenians still hiding in the town and burned them on a monstrous funeral pyre.

Who could still escape from the plain of Mush fled to the mountains of Sasun.”

Excerpted from: Lepsius, Johannes: Der Todesgang des Armenischen Volkes: Bericht über das Schicksal des Armenischen Volkes in der Türkei während des Weltkrieges. Reprint der Ausgabe Potsdam 1930, Heidelberg 1980, p. 117f.

Samuel Zurlinden: Failed Resistance

“Mush is located in a plain on the Upper Euphrates in the Vilayet Bitlis. It had already fought back in the first months of the year, and with success, and then a certain truce had been established with the government. On 1 May, however, three Armenians were hanged and, without cause, the Armenian quarter was surrounded by Turkish military. During the last week a certain Kiazim Bey arrived in Mush with at least 10,000 men and mountain artillery; the latter was commanded by German officers. Immediately strong sentries occupied the hills dominating the town and, in conjunction with Kurdish bands of ‘fedayis’ and policemen, prevented all traffic between the town and the villages of the surrounding area. Then the authorities demanded that arms be handed over from the Armenians in the town and a large sum as ransom. The notables and the local chiefs in the surrounding villages were subjected to outrageous tortures; they had their nails on fingers and toes torn out, as well as teeth. The female relatives of the victims who tried to help were publicly disgraced in front of the mutilated men. On the morning of 3 July, the real butchery began in Mush. The cannons were first directed against the upper part of the town, so that there the houses collapsed and a conflagration broke out. Some of those fleeing were cut down in the streets. The Armenians crowded together in the ‘Brut’ district and saw from there how their female relatives were violated, their brothers killed. Many took their own lives, including Tigran Zinoian with all the members of his family; some shot their wives and children to save them from desecration. A number of Armenians were still fighting and shot a lot of Turks and Kurds, only they could not stand up against the artillery fire under the German command. On the night of 4 July, a few thousand Armenians tried to break through the ranks of the Kurds and flee to the mountains of Sasun. The conflagration illuminated their way for a long distance, they were noticed and fired upon by the Turks, and many still lost their lives. The others managed to escape across the river. In the city, the last Armenian was soon incapacitated, and the soldiers were able to pounce without danger on the women and children, who were rounded up into large camps and stabbed with bayonets or put into barns and burned. Bishop Vardan also suffered flaming death in a barn with 260 captured notables. This is how people are treated in our time. (…) A German in Mush writes: ‘Every officer boasted of the number of people he personally put down as his contribution to the liberation of Turkey from the Armenian tribe.’”

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 2. Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918

“Once flourishing” and “allmighty”: Surb Karapet Monastery / Մշո Սուրբ Կարապետ վանք / Glakavank’ Գլակավանք

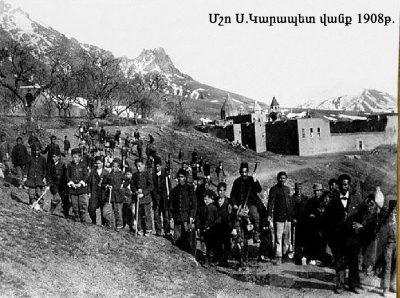

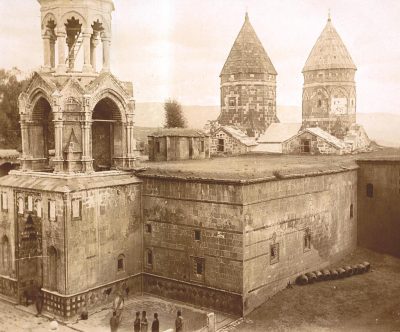

Surb Karapet Monastery was an Armenian Apostolic monastery in the historic province of Taron, about 30 km northwest of the city of Mush (Muş). From the 12th century until its destruction, the monastery was the seat of the diocese of Taron, which had an Armenian population of 90,000 (circa 1911). It was considered the largest and most eminent shrine in Western (Turkish) Armenia. It was the second most important Armenian monastery after Etchmiadzin. It attracted pilgrims and hosted large celebrations on several occasions annually. People from every corner of Armenia made pilgrimages to the monastery. They usually held festivities at the monastery’s yard. It was considered by believers to be ‘almighty’ and was renowned for its perceived ability to heal the physically and mentally ill. It remained a prominent pilgrimage site until the First World War.

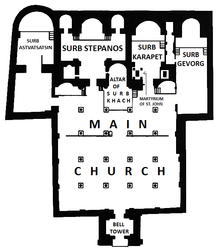

Surb Karapet translates to ‘Holy Precursor‘ and refers to John the Baptist, whose remains are believed to have been stored at the site by Grigor Lusavorich (Gregory the Illuminator) in the early fourth century. The monastery subsequently served as a stronghold of the Mamikonians—the princely house of Taron, who claimed to be the holy warriors of John the Baptist, their patron saint. It was expanded and renovated many times in later centuries. By the 20th century it was a large fort-like enclosure with four chapels. The monastery housed tombs of several Mamikonian princes as it was the dynasty’s sepulchral abbey. According to British traveler H.F.B. Lynch, the tombs of Mushegh, Vahan the Wolf, Smbat and Vahan Kamsarakan could have been found near the southern wall of the monastery.

The monastery was burned and robbed during the Ottoman genocide of 1915 and later abandoned. Its stones have since been used by the local Kurds for building purposes.

Names

The monastery was popularly known as Մշո սուլթան Սուրբ Կարապետ (Msho sultan Surb Karapet), literally translating to “Sultan Surb Karapet of Mush”. The epithet ‘Sultan’ was bestowed as a reference to its high status as the “lord and master” of Taron.

One of the common names was Glakavank (Գլակավանք), meaning “Monastery of Glak” after its first father superior, the Syriac Zenob Glak. It is sometimes spelled in English as Glaka vank (classical spelling: Գլակայ վանք; reformed spelling: Գլակա վանք) or Klaga vank (from Western Armenian). Due to its location it was also called Innaknian vank (Իննակնեան վանք in classical spelling, and Իննակնյան վանք in reformed), translating to ‘Monastery of the Nine Springs’.

History

Foundation to the Middle Ages

According to Armenian tradition, the site was founded in the early fourth century by Grigor Lusavorich (Gregory the Illuminator), who went to Taron to spread Christianity, following the conversion of King Trdat (Tiridates) III of Armenia. At the time, there were two pagan temples dedicated to the gods Vahagn and Astghik on the site of the cloister. They were presumably razed to the ground by Grigor Lusavorich, who erected a martyrion to house the remains of Saints Athenogenes and John the Baptist which he had brought from Caesarea. James R. Russell suggests that in Armenia some of the qualities of the pagan god Vahagn were passed down to John the Baptist. Folk belief held that devs (demons) were kept underneath the monastery; they would be released during the Second Coming by John the Baptist (Surb Karapet).

Zenob Glak, a Syriac archbishop, became the first father superior of the monastery. He is sometimes mentioned as the author of History of Taron (Patmutiun Tarono, Պատմութիւն Տարօնոյ), although the work is generally attributed to the otherwise unknown John Mamikonean and “scholars are convinced that the work is an original composition of a later period (post-eighth century), written as a deliberate forgery.” Its main purpose seems to be asserting the monastery’s preeminence. A relatively short ‘historical’ romance, it tells the story of the five members of Taron’s princely house: Mushegh, Vahan, Smbat, his son Vahan Kamsarakan, and the latter’s son Tiran, who were known as the Holy Warriors of John the Baptist, their patron saint. They defended the monastery and other churches in the district.

The 6th century chronicler Atanas Taronatsi (Athanas of Taron), best remembered for collocation of the Armenian calendar, served as its father superior. The monastery’s possessions were expanded in the seventh century, but the building was reduced to ruins by an earthquake in the same century. It was subsequently rebuilt and the chapel of Surb Stepanos (St. Stephen) was founded.

Christina Maranci suggested that the foundation of the monastery is “most probably connected with the rise of the monastic movement” in Bagratuni Armenia in the 940s. In the late ninth century, following the establishment of Bagratid Armenia, a school was founded at the monastery. In the 11th century Grigor Magistros built a palace within the monastery, but it was destroyed by fire in 1058 along with St. Gregory (Surb Grigor) Church which had a wooden roof. Following the death of the Sökmen II Shah Armen in 1185 the monastery was attacked by Muslims. Archbishop Stepanos was killed and the monks abandoned the monastery for a year.

Modern period

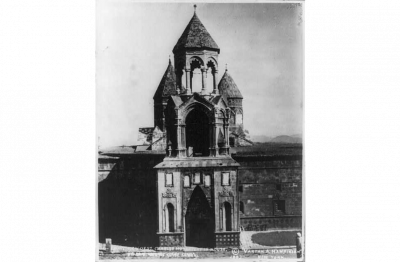

In the mid-16th century, the Surb Karapet chapel was built. According to the 17th-century traveler Evliya Çelebi the leadership of the monastery made large gifts to Turkish pashas in order to secure the monastic properties. From the 16th to the 18th centuries the monastery often sheltered Armenians fleeing the Ottoman–Persian Wars. In the 1750s, the Surb Karapet church was destroyed by Persian troops. In the 18th century, several earthquakes hit the monastery. The one in 1784 being especially devastating, destroyed the main church, the refectory, part of the bell tower and the southern wall. In 1788 the monastic complex underwent complete reconstruction—its gavit (narthex) was enlarged, and renovation was carried out in its belfry, the monks’ cells, scriptorium, ramparts and other sections.

19th century

In 1827 Kurdish gangs seized and looted the monastery, destroying the furniture and manuscripts. However, the monastery prospered at the beginning in 1862 when Mkrtich Khrimian became its father superior and, simultaneously, the prelate of Taron. Khrimian sought to reform the way donations were handled by establishing a council which would finance community projects. Before his reforms, most of the money went to the monks and affluent Armenians of the region who offered fierce opposition to him, including two attempts on his life. In his first year, Mkrtich Khrimian founded a largely secular school at the monastery, called Zharangavorats. Among others, the fedayi Kevork Chavush and Hrayr Dzhoghk, the singer Armenak Shahmuradyan, and the writer Gegham Ter-Karapetian (Msho Gegham) studied there. From 1 April 1863 until 1 June 1865 Khrimian published the journal The Eagle of Taron (Artzvik Tarono, «Արծւիկ Տարօնոյ») at the monastery. It was written in modern Armenian, and hence accessible to the common people. The journal sought to raise the national consciousness of the Armenians. Edited by Garegin Srvandztiants, a total of 43 issues were published. Khrimian left the monastery in 1868 when he became the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople.

According to two French travelers in 1890, the monastery possessed large areas of land and it took several hours to get from one end to another. The estate was covered by forests, arable fields and had three farms with around a thousand goats and sheep, a hundred oxen and cattle, sixty horses, twenty donkeys and four mules, which were taken care of by 156 servants. In 1896 an orphanage was founded next to the monastery. It housed a school for 45 children and a library.

According to H. F. B. Lynch, who visited the monastery in 1893, with the presence of the Kurdish threat and the suspicions of the Turkish government “this once flourishing monastery has been stripped of much of its glamour; indeed the monks are little better than prisoners of State.” The monastery was looted in 1895 during the Hamidian massacres. By the early 20th century, the monastery’s structure was deteriorating. The decline continued until the start of World War I.

Destruction and current state

During the Ottoman genocide of 1915 the monastery housed a large number of Armenians escaping the deportations and massacres. Turkish forces and Kurdish irregulars sieged it, but the Armenians within resisted for more than two months. According to contemporary reports, around five thousand Armenians were massacred “near the wall of the monastery”, while the monastery itself was “sacked and robbed”. According to the American missionaries Clarence Ussher and Grace Knapp, the Turks slaughtered “three thousand men, women, and children” gathered at the courtyard of the monastery on command of a German officer.

In 1916 the Russian troops and Armenian volunteers temporarily took control of the area and transferred around 1,750 manuscripts to Etchmiadzin. Among them is an 18th-century reliquary of the right hand of John the Baptist made of silver repoussé. The area was recaptured by the Turks in 1918 and, subsequently, ceased to exist not only as a spiritual center, but also as an architectural monument. It remained abandoned until the 1960s when Kurdish families settled on the site.

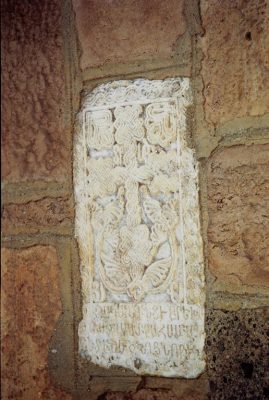

Many buildings in the village include stones from the monastery and khachkarner (cross stones), which are embedded in the walls. The remaining stones are “being systematically carried off by the local Kurds for their own building purposes.” According to historian Robert H. Hewsen, as of 2001, only traces of two chambers of the chapel of Surb Stepanos remain, while the rest of the monastery’s remains consist of “foundations and ruined walls“, which are used as barns.

In May 2015 Aziz Dağcı, the President of the NGO Union of Social Solidarity and Culture for Bitlis, Batman, Van, Mush and Sasun Armenians, made a formal appeal to the Turkish Ministries of Culture and Interior requesting the reconstruction of the monastery and the removal of all 48 houses and 6 barns on its former location. Dagcı stated that according to the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne the Turkish government obliged to preserve the religious institutions and structures of ethno-religious minorities, including those of the Armenian community. He added that he first forwarded a letter to government agencies in 2012 who promised to clean the site within six months.

Medieval Center of Learning: Holy Apostles Monastery of Mush / Մշո Սուրբ Առաքելոց վանք – Mšo Surb Arakelots vank’

Arakelots Monastery was an Armenian Apostolic monastery in the historic province of Taron, 11 km south-east of Mush (Muş). According to tradition, Grigor Lusavorich (Gregory the Illuminator) founded the monastery to house relics of several apostles. The monastery was, however, most likely built in the 11th century.

The great monastic complex of the Holy Apostles included several churches and chapels. It survived the destruction wrought by the hordes of Tamerlane and was repeatedly rebuilt and embellished, housing a major scriptorium. Of the several thousand manuscripts copied in Taron, some 1,700 were rescued during the Ottoman genocide and are now preserved in the Institute of Ancient Manuscripts (Matendaran) in Yerevan.[5]

During the 12th-13th centuries the Monastery of Holy Apostles was a major center of learning. It remained one of the prominent monasteries of Turkish (Western) Armenia until the Ottoman genocide of 1915, when it was attacked and subsequently abandoned. It remained standing until the 1960s when it was reportedly blown up. Today, ruins of the monastery are still visible.

Historian Movses Khorenatsi and philosopher David the Invincible are believed to have been buried in the monastery courtyard.

Names

The monastery was most commonly known as Arakelots, however, it was also referred to as Ghazaru vank (Ղազարու վանք; ‘Monastery of Lazarus‘), after its first abbot Yeghiazar (Eleazar). It was also sometimes known as Gladzori vank (Գլաձորի վանք), originating from the nearby gorge called Gayli dzor (Գայլի ձոր, ‘Wolf’s gorge’).

Official Turkish sources refer to it as Arak Manastırı, a Turkified version of its Armenian name. Turkish sources and travel guides generally omit the fact that it was an Armenian monastery.

History

According to Christina Maranci, evidence shows that the monastery was constructed in the latter half of the 11th century during the rule of the Tornikians—a branch of Mamikonians—who ruled Taron between 1054 and 1207. According to an inscription on a khachkar (cross-stone), it was renovated in 1125. In the east side of the monastery there were nine 11th century khachkarner with inscriptions.

In the following centuries it became a prominent educational center. The monastery school was active in 11th-12th centuries under chronicler and teacher Poghos Taronetsi (Paul of Taron), although it is known that translations were being made at the school since the 5th century. It flourished in 1271–81 under Nerses Mshetsi (Nerses of Mush), who later moved to Syunik and established the University of Gladzor in 1280.

Between the 13th and 16th centuries, various Turco-Mongol dynasties ruled Taron. In the 14th century it was destroyed by Tamerlane‘s invasions. The Ottoman Empire annexed the region in the mid-16th century. A defense wall was built around the monastery in 1791.

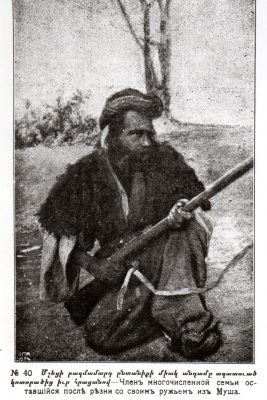

In November 1901 a skirmish between Armenian fedayi (irregulars) and the Ottoman forces took place in and around the monastery.

According to Jean-Michel Thierry, “the main church and chapels were still in a reasonably good state in 1960. Soon thereafter, however, they were reportedly dynamited by an official from Mush.”

Structure

The ensemble consists of a main church with two chapels, a narthex (zhamatun), and a bell tower.

Within monastery walls

The St. Arakelots Church—the monastery’s main church—was built in the 11th century. “It consists of an inscribed quatrefoil masked on the exterior by a massive rectangle. Barrel vaults top each of the four arms of the interior, as well as the corner chapels, which are two-storied at both east and west. A dome on squinches, now collapsed, once rested on an octagonal drum above the structure’s central bay. Interior decoration included wall painting, and in the apse one can still discern human figures, most likely representing apostles.”

It had only one door, on the western side. The church was constructed of brick and mortar. The church was renovated in 1614. Its floor plan was cross-shaped, it had a rectangular shape in the outside. The dome, restored in 1663, was an octagon in the outside. A rectangular gavit (narthex) was built in 1555 by abbot Karapet Baghishetsi (Karapet from Bitlis).

To the west there was a three-storey bell tower with eight columned rotunda built by Ter Ohannes vardapet in 1791. (It has been suggested that a bell tower probably existed earlier than that and was destroyed.) Its lowest floor survives.

On the foundations of a 14th-century church, the St. Stepanos (Stephen) chapel was built south of the main church in 1663. Composed of a single aisle terminating in an apse, it is now half-buried in rubble.

On the northern side, only ruins of the St. Gevorg (George) chapel could have been found.

St. Thaddeus Church

The St. Tadevos (Thaddeus), though not within the monastery walls, was located some 300 meters northeast. Dated to the 13-14th centuries by Jean-Michel Thierry, it was well preserved. On the exterior, it was well-polished tufa; on the inside bricks.

Cultural heritage

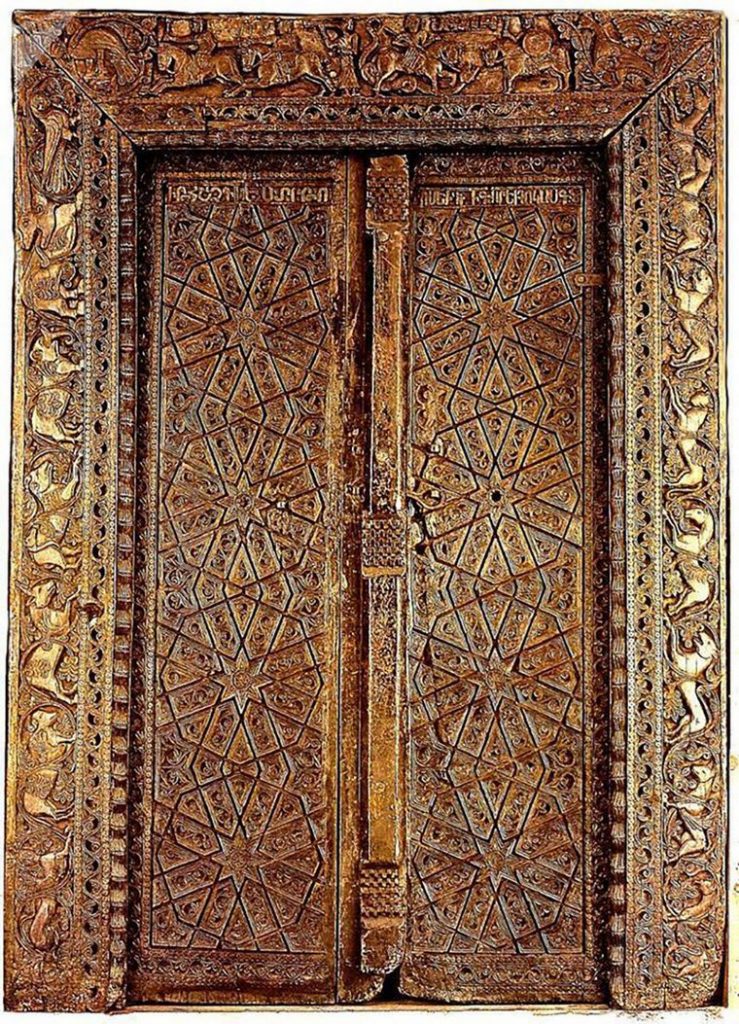

The wooden door

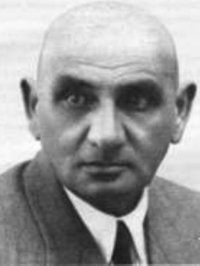

The wooden door of the Arakelots Church is considered a masterpiece and one the finest pieces of medieval Armenian art. It was created in 1134 by Grigor and Ghukas. It depicts non-religious, historic scenes. The front side probably shows a prince as he has a scepter on his right hand. During World War I, German archaeologists reportedly transferred it to Bitlis in hope to later move it to Berlin. However, in 1916 when Russian troops took control of the region, historian and archaeologist Smbat Ter-Avetisian (1875-1943) found the door in Bitlis, in a booty abandoned by the retreating Turks, and with a group of migrants brought the door to the Museum of the Armenian Ethnographic Association in Tbilisi. In the winter of 1921–22 Ashkharbek Kalantar moved it to Yerevan’s newly founded History Museum of Armenia.

Manuscripts

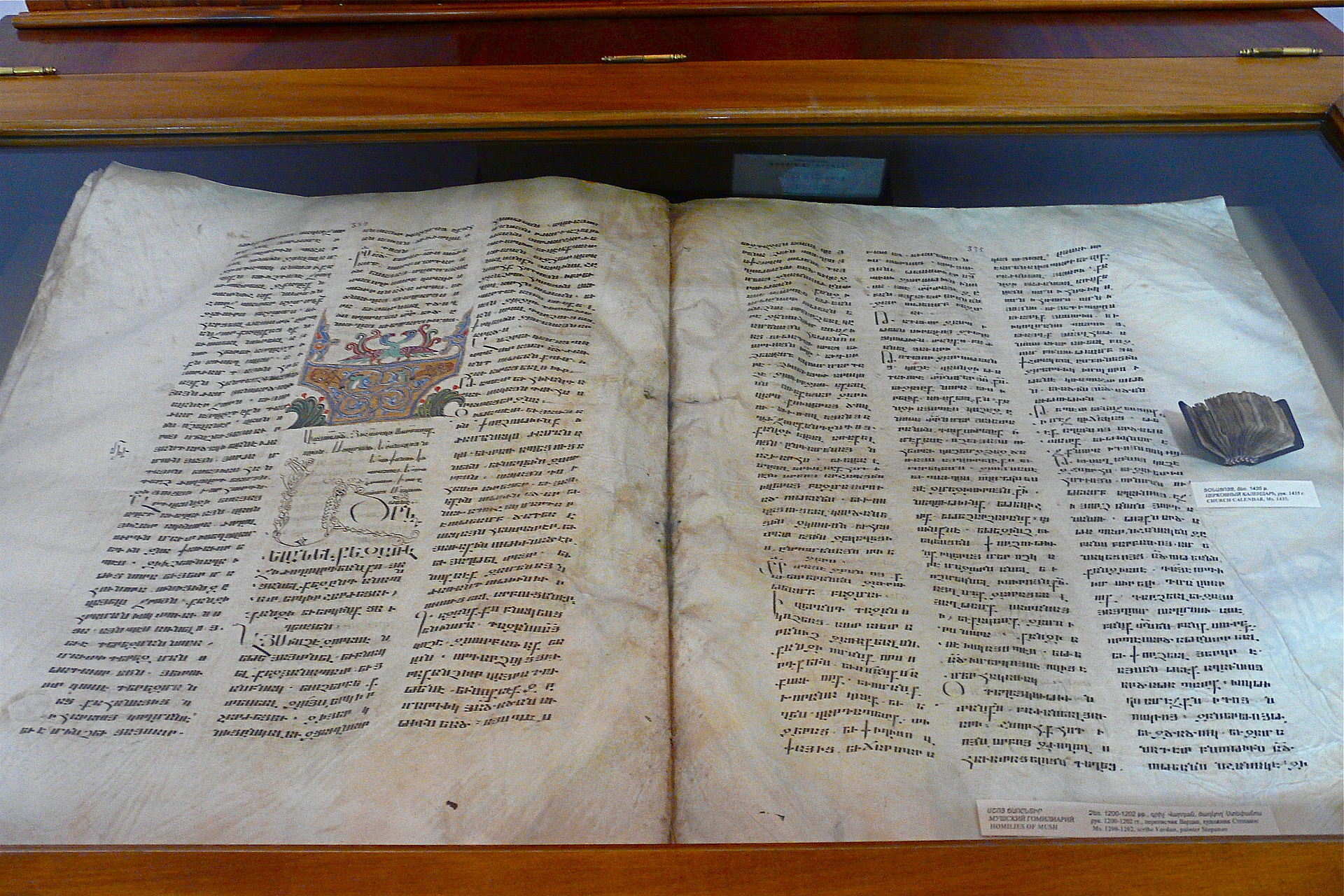

The Mush Homiliarium

Many manuscripts were preserved in the monastery. Notably, a manuscript named Homiliarium (Ms. 7729, commonly known as the ‘Mush Homiliarium’, «Մշո ճառընտիր» Mšo Č̣aṙəntir), the largest known Armenian manuscript. It was not created in the Arakelots Monastery, but rather in the Avag Monastery near Yerznka (Erzincan) between 1200 and 1202; written by the scribe Vardan Karnetsi, and illuminated by Stepanos. Written on vellum, it now has 601 pages and weighs 28 kilograms. It originally had 660 pages, 17 of which are now in Venice and one in Vienna. Two pages were transferred to Yerevan from the Moscow Lenin Library in 1977 which were separated in 1918. In 1202 it was robbed by a non-Armenian judge who sold it to the Arakelots Monastery in 1204 for four thousand silver coins collected by locals. It was kept there from its acquisition in 1205 until 1915. During the genocide it was taken to Tbilisi in two separate parts and later transferred to Yerevan. It is now preserved at the Matenadaran.