Balu (Trk., Western Armenian pronounciation: Palu) is located in the northwest of Diyarbekir province, between the lower reaches of the Eastern Euphrates (Grk.: Ἀρσανίας – Arsanias, Arm.: Aradzan; Trk.: Murat) and the mouth of its right tributary. The Ottoman kaza Balu almost corresponded to the historical canton of Balahovit with the village groups (nahiye) Garachor, Bulanık, Mazermat, Gökdere, Ochu, Hun, Charabeken, Sadadjur and Ashmushat. The Armenian villages were mainly located in Mazermat.

Balu is surrounded by hills and has fertile soils, a favorable climate and rich water sources. Here, wheat (65% of the cereal crops), barley (13%), millet, corn and cotton were grown. Horticulture and viticulture were also widespread.

Toponym

Balu (Grk.: Romanopolis; today: Palu; also: Bala, Balues, Paluis, Boulou, Pala, Palu, Polis) was the center of the ancient Armenian canton of Balahovit (also: Balahovit, Baliobit, Balovit, Baluhovit).[1] Some identify Balu with the Shebeter (or Pullerias, Puterias) mentioned in Urartian sources.

According to the legend, it was called Balu because of the large cherry forest on the spot. There are mentions that very large and tall trees were preserved in the vicinity of Balu in the middle of the last century.

History

The history of Balu goes back to the time of the New Assyrian Empire. King Šulma-nu-ašared III called the area the land of Išua. He passed through Palu in the middle of the 9th century BC against the northern tribes and empires like Urartu. A little later, the Urartian king Menua I reached the area and left a stele in Eski Palu (Old-Palu).

After the Urartians, the Macedonians, the Parthians, the Sasanid Empire, the Armenians, the Romans, the Byzantine Empire, the Arabs, the Kurds, the Dulkadir, the Ak Koyunlu and the Ottomans, among others, ruled here. Since the Ottomans’ victory over the Safavids in the 16th century, several autonomous Kurdish principalities, including Palu, have been established in eastern Anatolia.

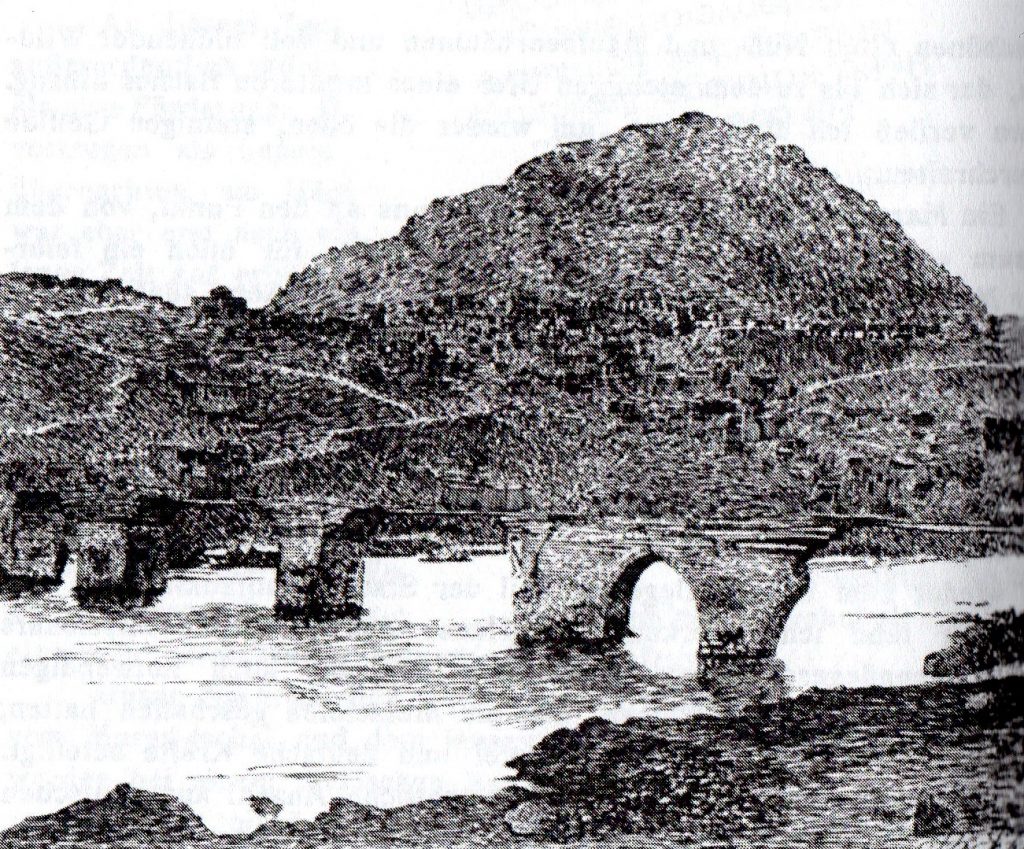

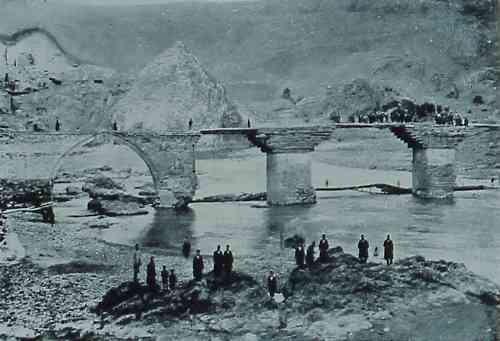

The town of Palu was fortified and until the 6th century it was the administrative center of the Balahovit canton of Armenia Maior. The fortress is located on a high cliff above the Eastern Euphrates (Grk.: Ἀρσανίας – Arsanias, Arm.: Aradzan; Trk.: Murat), where the stele of the Urartian ruler Menua I was found. Mesrop Mashtots, the founder of the Armenian alphabet, is said to have stayed here for seven weeks and to have developed the Armenian script. By the middle of the 19th century, the fortress was already in ruins and abandoned.

Population

At the beginning of the 19th century, the kaza Balu had a population of 100,000, of which 60-70,000 were Armenians, the rest Kurds and Turks. By the beginning of the 20th century, the number of Armenians had fallen to less than 25,000.

According to the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, 15,753 Armenians lived in 37 localities of the kaza before 1914, maintaining 38 churches, two monasteries and 26 schools with 2,050 students.[2]

The town of Balu had a mixed population of Armenians, Turks, Kurds, Syriacs, Greeks, totalling about 6,000 in 1830-1850 and 10,000 in 1914, “5,250 of whom were Armenians.”[3]. Half of the population has always been Armenians, who lived in four districts of the city, engaged in the cultivation of grain, cotton, flax, hemp, fruits, viticulture, silkworm breeding, beekeeping and animal husbandry. Balu’s grain and fine wine were well-known and sold in neighboring areas. The Armenians of Balu were skilled craftsmen, engaged in linen weaving, shoemaking, as well as trade.

The Armenian inhabitants of the town maintained five churches (Kaghtsrahayats Surb Astvatsatsin, sometimes referred to as a monastery, Surb Grigor Lusavorich, Surb Sahak Parkev, Surb Kirakos, and Surb Nargis) and four co-educative schools for 250 students (girls and boys). They owned 14 stores and workshops as well as some mills. In the surroundings there were coal and copper mines.

Densely populated by Armenians, the town of Palu was also a center of commerce and crafts. [Rev. Boghos / Poġos / Poghos] “Nathanian, having visited Palu in 1878-9, attests the following concerning the activity of Armenians there:

‘Merchandise for twelve thousand pounds per annum is imported into Palu. Most of the importers and exporters of the articles are Armenians. There is a market of medium size where there are about three hundred shops, two caravanserais built of brick and stone, and four bakeries. Most of the craftsmen and traders of this market are Armenians.’”[4]

According to the 1970 census, the city of Balu had a population of 403,800, including forcibly Turkishized Armenians, barely 600-700.

Armenian Wedding Song “The City of Balu is Under Construction” – «Բալու քաղաք շինվեր է»

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rBs7ZR5MqAk

A list of the villages in the kaza Balu inhabited by Armenians can be found on this website: https://etnikhalklar.wordpress.com/2019/03/22/genocide-in-the-district-of-palu-prior-to-the-genocide/

Destruction: 1895

The kaza Balu was particularly affected by the anti-Armenian massacres and riots of 1895. “Armenian villagers were assaulted, and gendarmes and Kurds were committing ‘all kinds of exactions and outrages,’(…)”.[5] “In one Palu-area village, Turks tore down a church ‘and it is [now] used as a privy.’”[6]

“Palu, home to an estimated 15,000 Armenians, saw 900 deaths. Six villages were razed and seven ‘half-burned.’ [The British vice-consul in Van, Cecil] Hallward counted 195 women and girls abducted and ‘a large majority’ of the Christian females aged 12–40 ‘violated.’ In one village, Yeniköy, Christians took refuge ‘with a certain Shukri Bey who, with his servants, [then] violated all the young women and girls.’ The ‘worst man’ in Palu district, according to Hallward, was the mufti, who ‘was very active in the massacre and killed the principal Protestant, Manoog Aga, with his own hand.’”[7]

Three thousand were forced to convert in Balu kaza.[8]

“Much as rape and abduction preceded the massacres, they continued afterward. In Harput, the killings and arson occurred in November 1895, but [Caleb F.] Gates, [president of the missionary-run Euphrates College,] complained in January 1896 that ‘the Palu Turks still continue to carry off girls and women, keeping them a few days and then returning them with their lives blasted.’”[9]

“Until spring 1915, the only problem we know of was the violence of the military requisitions and toward the end of February [1915], the enrollment of new Armenian draftees in the amele taburis. In the same period, the only two Armenian gendarmes in Palu were dismissed, for no apparent reason. (…) The first alarm came in April 1915, when the town’s leading personality, the pharmacist Karekin Kiurejian, was arrested and sent to Dyarbekir. He was soon followed by two Hntchak activists, the brothers Hampartsum and Mgrdich Kozigian. The order to search peoples’ homes for arms was issued by the kaymakam, Kadri Bey, very shortly thereafter. (…) The biggest Armenian village, Havav, which had, 1,648 inhabitants, was the first to be searched. It was surrounded by 150 armed men led by the mayor of Palu; 70 notables were arrested – among them Thomas Jelalian, Vahan Der Asdurian, Manug Navoyian, and Sisag Mkhitar Baghdzengian – and jailed in Palu. They were subsequently taken to Palu Bridge in a convoy of 200 men and slain in the nearby gorge of Kornak Dere, after which çetes commanded by Teyfeş Beg çetes threw their bodies into the river.

The other Armenian villages of the kaza were cut off from each other and then, in the first half of June, were attacked by çetes under the command of Ibrahim, Tuşdi, and Teyfeş Beg. All the men were stripped and shot on the banks of the Euphrates; their corpses were thrown into the river. In the village of Til (…) only one miller was spared, so that he could continue to provide the town with flour.

On 1 June, 800 men of the amele taburi stationed in Khoshmat, north of Palu, all of them from Eğin or Arapkir, as well as 400 worker-soldiers based in Nirkhi, where they had been working for seven months, were tied together and killed with knives by the ‘butchers of men’.

Palu’s prison rapidly filled with schoolteachers and merchants who had been arrested in the administrative seat of the kaza. The pivotal point of the genocidal system set up in the kaza, however, was the famous medieval bridge with eight arches that spanned the eastern Euphrates near the exit from the town. Squadrons of çetesoperated there in three killing fields under the immediate command of the kaymakam Kadri Bey (…). All the men of Palu were slain here. In the first half of June 1915, Palu Bridge was also a point of passage or massacre for some 10,000 deportees from the vilayet Erzurum, especially for the kaza of Kiği. (…)

The women and children from the rural zones were first transferred to Palu and confined in the courtyard of the Church of St. Gregory the Illuminator for two weeks. The male population came to pick out young women, who were raped and then returned after a day or two. The turn of the families from Palu came next: Their houses were systematically plundered, with the exception of a few that had been earmarked for Turkish notables. Very young children were then separated from their mothers, packed into barrels, and thrown into the Euphrates. A few young men and a few families succeeded in fleeing to the mountains, where they survived by living in caves before reaching Dersim at the beginning of winter 1915. In early July, several hundred women, old men, and children from the area were finally sent away in a convoy that passed by way of Maden, Severek, Urfa, and Bilecik. Bishop Kalpakjian and Father Mushegh Gadarigian were not arrested until late June. They were killed near Palu, in the vicinity of Sınam, by a certain Reşid.”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 370f.

The Kemalist Nationalists continued the deportation policy. They “(…) initiated a countrywide push to expel the last of the Armenians (alongside the Greeks), but without explicitly enunciating the policy. In October 1922 some 350 Armenians, mainly from Malatya but some from Harput and Palu, were effectively deported to Aleppo.”[10]

“In dribs and drabs, the Armenians streamed southward from across Anatolia, though there was a brief let-up after the Lausanne Treaty was signed. Letters from émigrés describing poor conditions in Aleppo may also, for a time, have stalled new departures from Anatolia to northern Syria. Nonetheless 800 reached Aleppo in August 1923, mainly from Malatya, Arapgir, and Harput. Another 600 arrived in November, mainly from Malatya, Harput, Arapgir, Eğin, and Palu. Hundreds more arrived in January 1924, 160 of them from Garmouj, near Urfa.”[11]

The Testimony of Katherine Magarian (born Chakoian)

Katherine (Chakoian) Magarian (1906-2000) was a notable Armenian Genocide survivor, born in the village Baghin of the kaza Balu. Her personal testimony was first published in The Boston Globe article ‘Voices of New England’ (19 April 1998). In the years following, her testimony has been published in several books, including Hate Crimes by Laurie Willis; used as historical reference for genocidal literature. Most most recently a children’s book based on Katherine’s testimony, entitled The Crochet Angel.

“I saw my father killed when I was nine years old. We lived in Palou, in the mountains. My father was a businessman. He would go into the countryside, selling pots and pans, butter and dairy products. The Turks, they rode in one day and got all the men together, bringing them to a church. Every man came back outside, their hands tied behind them. Then they slaughtered them all, like sheep, with long knives.

They all died, 25 people in my family died. You can’t walk, they kill you. You walk, they kill you. They did not care who they killed. My husband, who was a boy in my village but I did not know him then, saw his mother’s head cut off. The Turks, they would see a pregnant woman and cut the baby out of her and hold it up on their knife to show those around.

My mother and I, we started running. They got one of my sisters and then one of my other sisters, she was four, but she ran away. My mother was hit by the Turks, she was bleeding as we went. We walked and walked, and I was saying ‘Ma, wait, I want to look for my little sister,’ but my mother slapped me, saying “‘o! Too dangerous, we keep walking.’ It got darker and darker, but we walked. Still, I did not know where. The Turks had taken over our city.

Two, three days we walked, with little to eat. Finally, we found my sister who had run away. Then we walked to Harput and I see the Turks and I want to run, but they are friendly Turks, my mother told me. She said, ‘You go live with them now, you’ll be safe,’ and I was. I worked there, waiting on them, cleaning, but I was alive and safe. But I did not see my mother for five years. She was taken to the mountains to live, and she saw hundreds of dead Armenians, hundreds of them, who had been killed by the Turks, the bodies were all over.

Years later, my mother said to the Turks, ‘I want to see my child,’ and they let her come back. She came to the house at night. She did not know me, but I knew it was her. Her voice was the same as I remembered it. I told her who I was, and she said, ‘You are my daughter!’ and we kissed, hugged, and cried and cried.

My mother later heard of an orphanage in Beirut for Armenians, and we went there after the Turks kicked us out of our country. I spent four years there, and again, I didn’t see my mother until a priest got us together. In 1924, she came to this country to meet family who left before the genocide. Three times now, I have lost my mother.

Sometimes, near the anniversary of the slaughter, my mind goes back there. You know, when I was 14, maybe 15, I have a dream, Jesus comes to me and says ‘Give me your hand,’ and I want to get up and go with him but I cannot get up. Then I am in the mountains, where all the dead were that my mother would later tell me about, and I see flowers, every kind of flowers, no bodies, and it is beautiful. Then I see the ocean and a boat, the boat that would take me to Cuba years later. I think this was God saying to me that I would be fine. I was lucky to live, I guess. God made me lucky.”

Quoted from: http://www.aina.org/news/20071113113103.htm