The Toponym

The oldest recorded name of the town is Polemonion (Ancient Grk.: Πολεμώνιον, Latinized as Polemonium), after Polemon I of Pontos, the Roman client king appointed by Mark Antony. A derivative of Polemonion, i.e. Bolaman, is the modern name of the river passing through Fatsa (the ancient Sidenus). The present name, Fatsa, has been influenced by modern Greek Φάτσα or Φάτσα Πόντου (φἀτσα is derived from Italian faccia), which translates as ‘face or housefront on the sea’, but has in fact mutated from Fanizan, the name of the daughter of King Pharnaces II of Pontos, through Fanise, Phadisana (Grk.: Φαδισανή), Phadsane, Phatisanê, Vadisani (Grk.: Βαδισανή), Phabda, Pytane, Facha, Fatsah into today’s Fatsa. Apart from Polemonion, another Greek name of the town was Side, after the ancient name of the river Sidenus. It is possible that Fatsa was mentioned by Strabo in the 1st century A.D. in the form of Phábda. In Byzantine times it was called Phádissa.

History

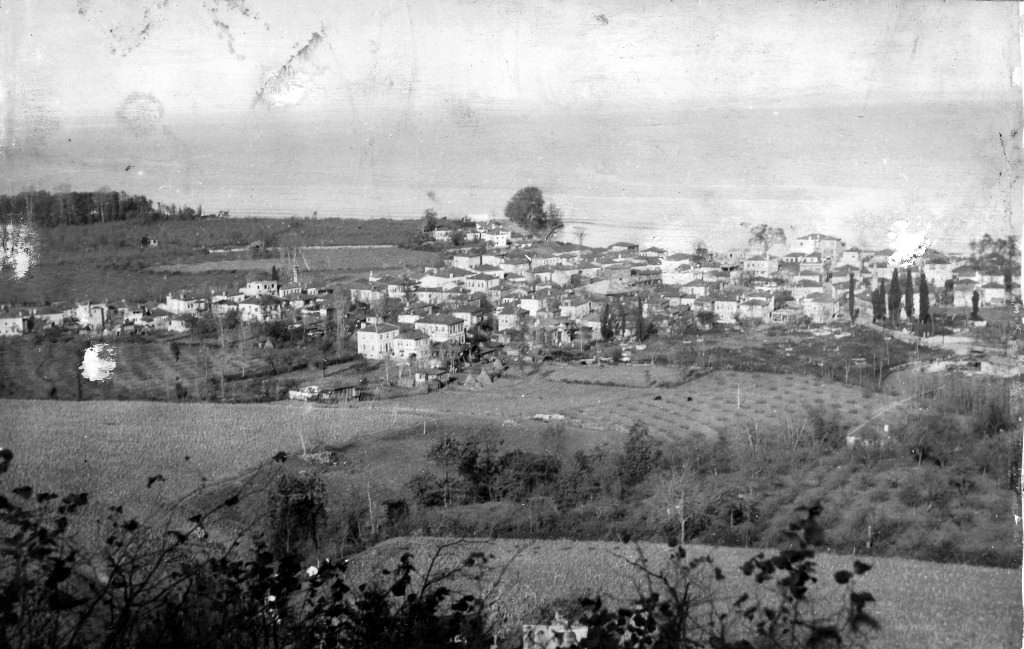

The history of Fatsa goes back to antiquity, when the coast was settled by Cimmerians, and Pontic Greeks in the centuries B.C. The ruins on Mount Çıngırt (ancient rock tombs and vaults) are from this period.

Roman and Byzantine periods

Under Nero, the kingdom became a Roman province in A.D. 62. In about 295, Diocletian (r. 284–305) divided the province into three smaller provinces, one of which was Pontus Polemoniacus, called after the Roman client-king Polemonium I, which was its administrative capital.

As the Roman Empire developed into the Byzantine Empire, the city lost some of its regional importance. Neocaesarea became the capital of the province, and the Diocese of Polemonion was a suffragan of the metropolitan see of Neocaesarea. Due to partition of the Byzantine Empire as a result of the Fourth Crusade, Fatsa became a part of the Empire of Trebizond in 1204.

In the 13th and 14th centuries Genoese traders established trading posts on the Black Sea coast. Fatsa became one of the most important of these ports. There is a stone warehouse on the shore built in this period.

Ottoman period

Following the conquest of the Empire of Trebizond by the Ottomans in 1461, Fatsa become a part of Rûm Eyalet (‘The Roman Province’) and later a part of Trebizond Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire and remained within the sancak of Canik until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in 1921.

Population, Migration, Expulsion

During the Byzantine period, as early as the 9th century, an Orthodox diocese was located in Fatsa (Diocese of Polemonion). Fatsa’s Christian population during the Ottoman era was made up by Pontic Greeks and Armenians, who thrived as craftsmen and bureaucrats.

The development and composition of the population of the city and region of Fatsa bears witness to intensive migratory flows during the Ottoman rule.

Following the Turkish conquest of Anatolia by the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum and later by the Ottomans, Muslims settler arrived at Fatsa in the middle of the 14th Century. The early Muslim Turkish settlers included Turkomens, whose descendants make up the majority of Fatsa’s current Alevi Muslim community.

In the second half of the 19th century, Fatsa’s Sunni population increased significantly, as some of Chveneburi (Sunni Muslim Georgians) from Batumi and Kobuleti (Turkish: Çürüksu), who fought in the Ottoman army against the Russian forces in Russo-Turkish War (1877–78) under Ali Pasha of Çürüksu and some of the Abazins and Circassians, who were forced to leave their ancestral land in North Caucasus after the end of the Caucasian War in 1864, were settled in Fatsa and in the surrounding villages. The Circassian immigrants had an immediate impact on the local economy by introducing silk production to the area. In 1868, 3 million piastres worth of silk was sold in Fatsa.

The majority of the Muslims living in Fatsa were from Sürmene, Rize and Georgia while the Greeks of Fatsa moved there from Argyroupolis [Trk.: Gümüşhane], Ünye, Ordu and Sürmene.[1]

In the early 20th century, Fatsa town had a population of 3,000 of which approximately 1,000 were Turks and the remainder were Greeks, both Orthodox and Evangelists.[2] The last Ottoman census (1914) deviated from it by stating a total population of 40,339 for the whole kaza, of which 12 percent are said to have been Christians. According to a 1911 statistical survey on ‘Greek villages in Pontos’, however, there lived 7,200 Greek Orthodox Christians in the kaza Fatsa, in 18 communities, maintaining 18 schools, and 9 ‘private churches’. 18 further churches were Catholic.[3]

In 1919, in Fatsa town there were 8 churches (Greek Orthodox, Greek Evangelical and Armenian Apostolic) served by 9 priests.[4] After the departure of the last Christian community in 1923, the churches were closed and later demolished.[5] The last remaining church in Fatsa was in town’s Kurtuluş District and was demolished in the late 1980s.

The Greeks of Fatsa belonged to the Diocese of Neocaesarea and Ineos while the Evangelists belonged to the Diocese of Merzifon. The Greeks resided in the two Greek precincts: Rum Machlesi and Yiali Yeni Rum Machlesi in the south-west part of the town. The Greeks of Rum Machlesi supported the operation of an 8-grade boys’ and girls’ school and a 6-grade school for the Evangelical community. The majority of the Greeks of Fatsa were involved with merchant trades and shipping.[6]

“The 3,330 Armenians of the kaza of Fatsa lived in the principal town of the kaza, Fatsa, and in the villages of Çubukluk and Kaya Ardi. It seems that part of the population agreed to convert to Islam in order to avoid being deported, but that these people were finally deported to the south somewhat alter, with the exception of a miller. As in the kazas of Bafra, Çarşamba, and Ünye, so here, too, between 100 and 200 people took to the maquis under the command of Yaghjian, Minasian, and Hamalian. The handful of survivors discovered after the war came from this group.”[7]

The Armenian community in the Fatsa kaza maintained three churches and three schools.[8]

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Fatsa’s Christian population diminished. The last Pontic Greek community left Fatsa in 1923 as a part of the forcible Population exchange between Greece and Turkey, when 770 Muslim families from Thessaloniki, Greece were settled in Fatsa and the indigenous Pontic Greek population of Fatsa was settled in Katerini and in the village of Trilofos Himachal, both in the Pieria region of Greece. Two members of Fatsa’s Pontic Greek community, after the population exchange in 1923, became politicians in Greece: Alexander Deligiannidis, born in Fatsa in 1914 served in the Greek Parliament as a member of National Radical Union Party (1956 – 1964) and Takis Terzopoulos, born in Fatsa in 1920 served as the mayor of Katerini (1964 – 1967).

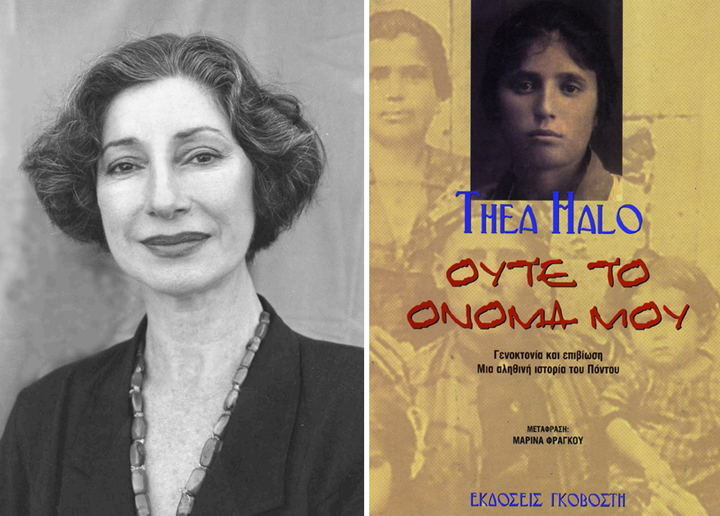

Thea Halo: Death March from Fatsa (Spring 1920)

In her book, the author describes the fate of her Pontic Greek mother Themia. She, her younger siblings and her parents were deported south from the mountain town of Fatsa in the spring of 1920 on Mustafa Kemal’s orders. The mother’s experiences, told in the first person, include an account of the death of a child:

“Was it on that day that little Maria died? I don’t remember. I only remember her little body tied to Cristodoula’s back like a papoose, her little hand bobbing back and forth, and the realization that something was wrong crept up on my hot body with a cold, clampy panic.

‘Mama’, I said as calmly as I could, hoping my calmness would make everything all right. ‘Maria looks funny.’

Mother looked up and burst into tears. Maria’s face had turned ashes. Her eyes stared out at nothing like little doll eyes that were broken in an open position, and her head rolled back and forth with each step.

‘What’s wrong?’ Cristodoula demanded in a panic. ‘What is it?’

We stopped in the road like a pile of stones in a river; the weary exiles ruptured out around us and continued their march. Mother took Maria from Cristodoula’s back and cradled her in her arms as her tears washed Maria’s lifeless face.

‘My baby’, Mother said.

She held out Maria for the soldier to see, as if her shock and grief would also be his.

‘Throw it away if it is dead!’ he shouted. ‘Move!’

‘Let me bury her’, Mother pleaded, sobbing.

‘Throw it away!’ He shouted again, raising his whip. ‘Throw it away!’

Mother clutched Maria’s body to her breast as we stood staring up at him. Her was grippled with a torment I had never seen before. Father reached for Maria, to put her down I suppose, but Mother snatched her even more tightly. Then she walked over to the high stone wall that separated the road from the town and lifted Maria up to lay her on the wall’s top as if on an altar before the Almighty.”

Excerpted from: Halo, Thea: Not Even My Name: From a death march in Turkey to a new home in America; a young girl’s true story of genocide and survival. New York: Picador USA, 2000, p. 134f.