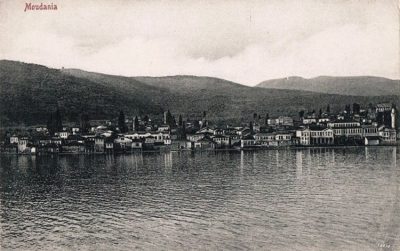

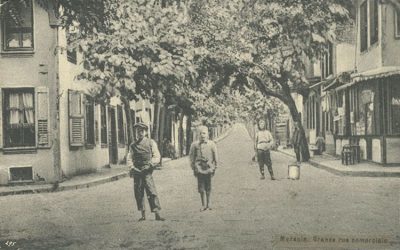

The hilly peninsula of Yalova at the South-Eastern Marmara littoral is situated between the Gulfs of Mudanya and Izmit (Ancient Greek: Ὀλβιανὸς κόλπος, romanized: Olbianos kolpos). It comprises the area between the towns of Gemlik, which was the administrative center between 1919 and 1922, and the town of Yalova (Gr. Pylai or Pylae – Πύλαι; ‚Gates‘), including the hinterland of the Iznik district. The placename Yalakova (‘Lowland of the Yalak’) is first documented in the year 1484. Sevan Nşanyan (Index Anatolicus) assumes that the current settlement Yalova appeared only in the 18th century.

Population

As a result of massive state sponsored Muslim immigration since the 19th century, the ethnic and religious composition of the population of the Yalova Peninsula had become highly diversified[1], but there still remained local urban Christian majorities, while 35 of the overall 40 villages in the kazas of Yalova and Gemlik were classified by an Allied Commission in 1921 as ‘exclusively Turkish’[2]. According to the Turkish demographer Kemal Karpat, the total pre-war population of the four administrative units, or sancaks in question was 1,631,728 residents. Of these, Greek Orthodox Ottomans, or rumlar, with 221,003 formed the largest non-Muslim group, followed by the ermeni millet-ı, or Armenian-Apostolic church-nation, a denomination with 125,342 persons.[3] The Muslim majority population of 1,216,680 comprised mainly ethnic Turks, Albanians and Slavonic refugees from the Balkans, i.e. Pomaks and Bosnians.

More than 30,000 of the Muslim population in this region were Circassian muhacılar, who settled predominantly in the east of the Yalova Peninsula.[4] The fact that Circassians, too, became victims of Kemalist revenge killings during 1920 and 1921 indicates that the Yalova crimes were not merely caused by the traditional religious divide between Muslims and Non-Muslims, but also by the ethnic divide between Turks and Non-Turks, and more so by political affiliations and military alliances.[5] The politically motivated victimization included even ethnic Turks: A report from Bursa of 11 August 1920 mentions as an example the Turkish village of Söyles (Sölöz) that “was burnt by the Nationalists, and five of the inhabitants perished. The survivors fled to the Armenian village of same name and begged for shelter”.[6]

According to the French-Armenian historian Raymond Kévorkian, the kaza of Yalova had a population of 1,640 Armenians, residing in a cluster of villages at the Black Sea coast (Şakşak, Kuruçeşme, and Kılıc). “Five kilometers to the south, on the road to Bursa, were two more Armenian villages – Çukur, home to 420 Kurdish-speaking Armenians from an area south von Van, and Kartsi/Lalıdere, which had 1,264 inhabitants. (…) In Yalova and its environs it was Ruşdi Bey, holding the post of kaymakam from 9 February 1913 to 31 December 1917, who organized the deportation of the Armenians and oversaw the seizure of their property.”[7]

November 1918-1922

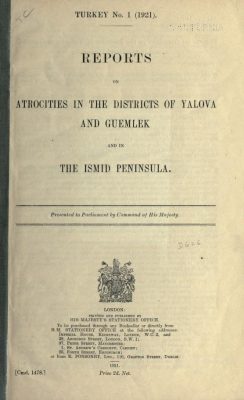

After its capitulation of 30 October 1918, the Ottoman Empire came at least nominally under the military and administrative control of the victorious Entente states. Three of them – Russia, France and Great Britain – had in a joint note of 24 May 1915 urged the Ottoman war regime to end its persecution of the Armenian population, announcing at the same time that after the war they would hold all members of the Ottoman government responsible for their “crime against humanity and civilization”.[7]

After the war, but in the same spirit of punitive justice, the British High Commission at Constantinople appointed at the first meeting of its Armenian-Greek Section the following five work sub-divisions:

- “Turkish offenders

- Relief

- Land and property (repatriation and restitution of property)

- Islamized Christians and Christians in Turkish hands

- Greeks, Armenians etc. in Turkish prisons”.[8]

To say the least, none of these missions could be fully accomplished during the period of 1919 to 1922. The reasons are complex: First of all, at that stage the Ottoman Empire was a failing state, whose civilian authorities were either no longer functional, or “venal and corrupt”, as the mentioned above Allied Yalova Commission found in 1921[9]; if administrative bodies still existed, they were far from being impartial. Most would collaborate with the Kemalists, fighting the Ottoman government in Constantinople, some, however, collaborated with the Hellenic Army.

Immediately after the Armistice, the Ottoman government at Constantinople half-heartedly collaborated with the Allies in the legal prosecution of those, who were considered politically responsible for the extermination of the Ottoman Armenians during the Great War. But when it became obvious after the Treaty of Sèvres (10 August 1920) that the Allies intended the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire instead of preserving its territorial integrity in the pre-war borders of 1914, the Ottoman willingness for collaboration dwindled rapidly.

Second, there existed an open antagonism between the Sultan’s government at Constantinople and the rebellious nationalist government at Ankara that emerged in May 1919 under its charismatic and successful leader Mustafa Kemal, who soon started to openly fight both the ancien régime of the Sultan and the Allied occupiers in the name of liberty and anti-imperialism. In this situation, the Allies failed not only to bring the perpetrators of the First World War to justice for recent crimes against Ottoman Christian subjects, but also to prevent or at least punish subsequent crimes.

Killings, massacres and even deportations were committed under the pretext and in the course of the Kemalist ‘liberation war’, with the clear aim of preventing in the first place the repatriation and resettlement of Armenian and other Christian survivors of previous deportations and to achieve the extermination of the rumlar residents, which was and remained the largest Christian ethnicity in numbers. As in earlier periods, public insecurity was an ardent issue, for likewise politically and criminally motivated highwaymen and bandits continued to threaten, rob and kill primarily the Christian population. The Allied High Commissioner at Istanbul and British Admiral of the Fleet John de Robeck characterized the situation in a report of November 11, 1919:

“(…) the Christians are now bewildered and terrified… Every district has its band of brigands now posing as patriots and even in the vicinity of Constantinople robbery under arms is of daily occurrence, the principal victims being naturally the unprotected Christian villagers. Behind all these elements of disorder stands Mustapha Kemal… The government cannot and will not move a finger to help the Christians.”[10]

Hellenic forces, to which the Allies had entrusted the protection of the indigenous Christians of Asia Minor[11], did not arrive until July 1920[12]. In previous months, during direct Nationalist-British military confrontation, the districts of Bursa and Iznik, and the peninsula and city of Izmit[13] were terrorised by Kemalist paramilitaries, or çeteler, frequently supported by the local Turkish population. Their commanders were regional or local brigand leaders, such as a certain officer Cemal Bey, who was also responsible for the Iznik Massacres of August 14-15, 1920.