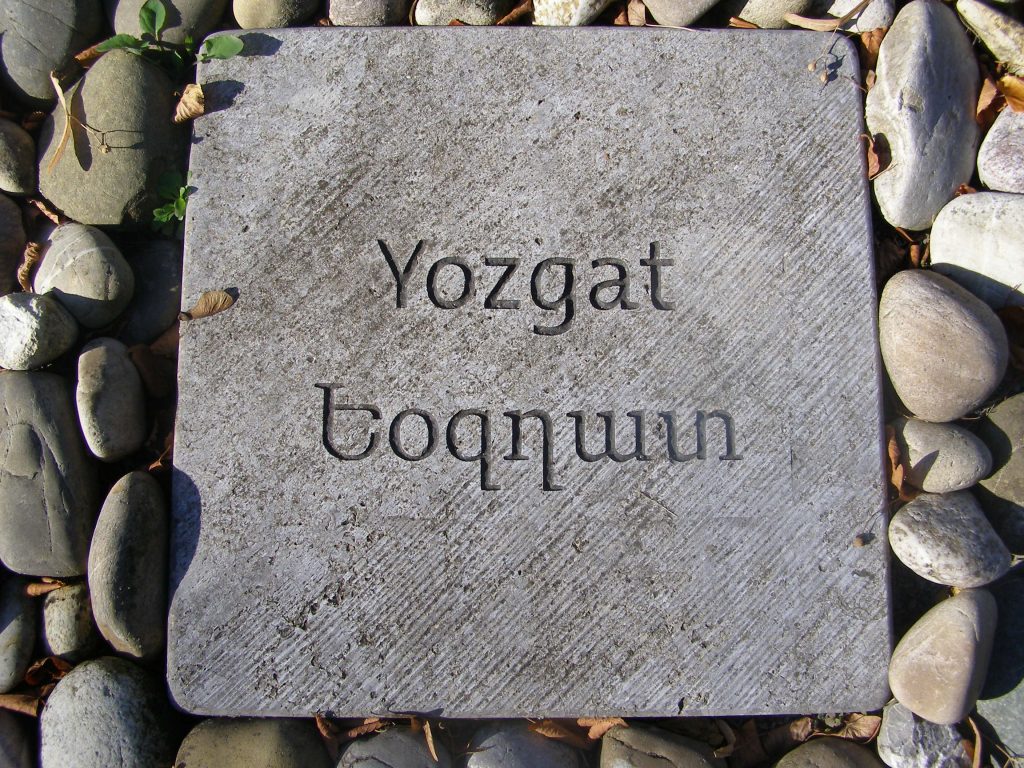

Armenian Population

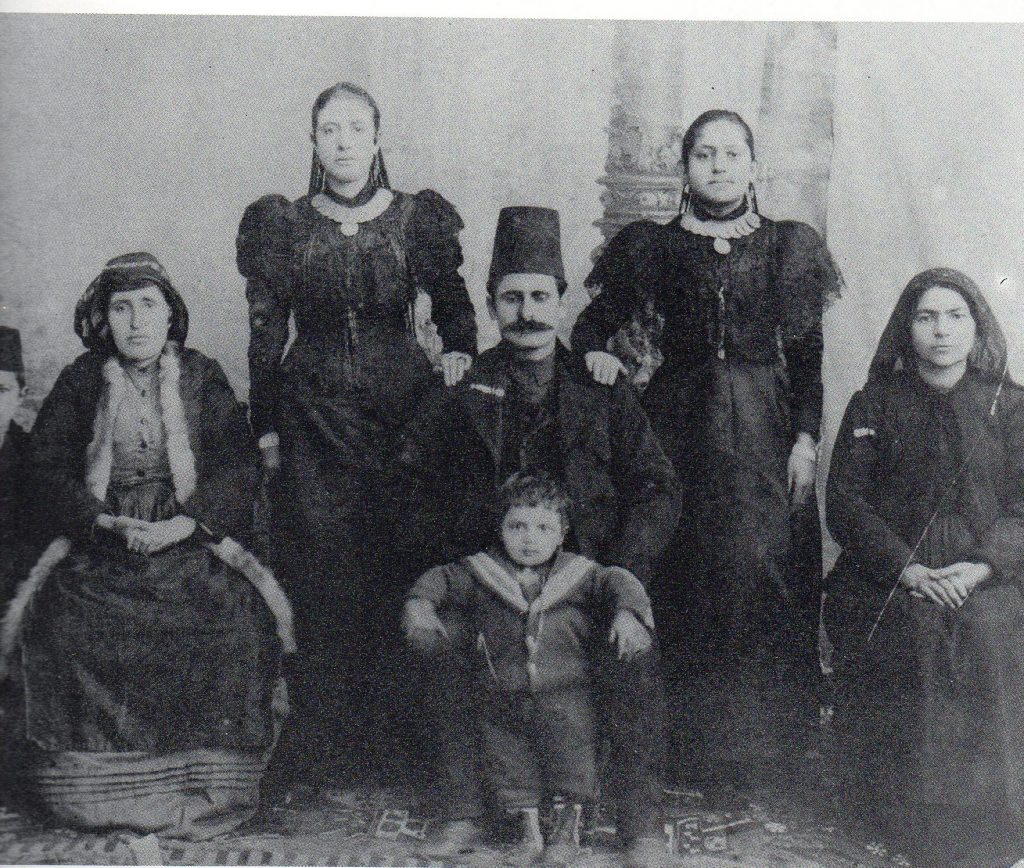

In 1914, 13,696 Armenians lived in four localities of the district of Yozgat, which at that time belonged to the province of Ankara. They maintained five churches and six schools with an enrolment of 3,300 pupils.[1]

Destruction

On 8 August 1915, four hundred seventy-one Armenian notables from Yozgat were arrested and deported. Soon afterwards, a second group made up of 300 men was sent to Dere Mumlu, a spot some four hours from the town, and liquidated.[2]

Almost all Armenians of the sancak of Yozgat were massacred or deported. The genocide in this sancak was the subject of the so-called Yozgat trial, a court-martial, in early 1919 (cf. below).

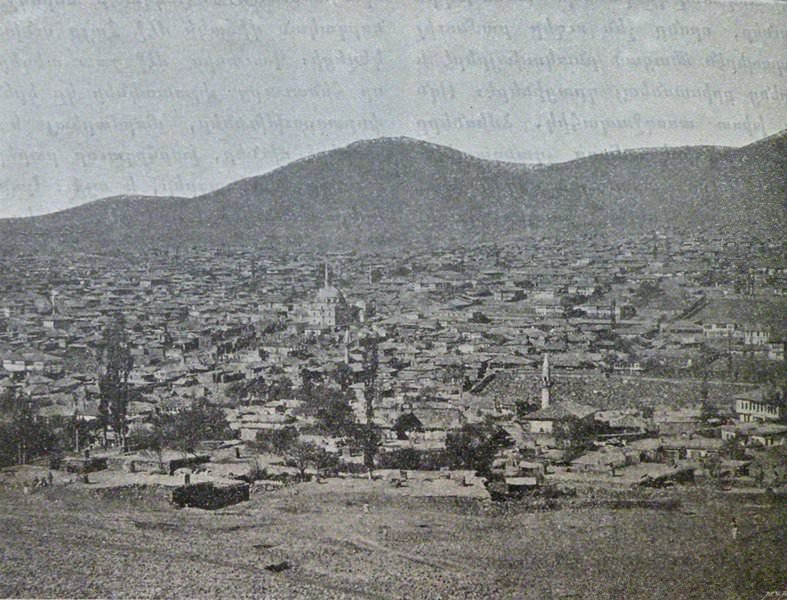

Town of Yozgat

The town of Yozgat was founded in the first decades of the 18th century by Armenian artisans.[3]

Population

“In 1914, the 9,520 Armenians residing in the town represented 40 per cent of the population. Near Yozgat, there were three Armenian villages: Incirli (pop. 1,000), Daneşman (pop. 250), and Köhne (pop. 2,000). There were also a few small Armenian communities scattered throughout the kaza.”[4]

There were Greek villages in the vicinity of Yozgat town.[5]

Destruction

“In Yozgat the Armenians were ordered to leave the city within two hours. On the way, the men were segregated. The soldiers tied five each with willow rods, laid their heads on felled tree trunks and beat them to death with clubs.“[6]

On 22 August 1915, the first convoy from Yozgat, comprising some 2,000 women and children, left the town toward the south. On 27 August they were surrounded at Karahacıli by Turkish and Circassian villagers and exterminated, with the exception of some young women and children, who are abducted to be sold.[7]

The Kemalists occupied Yozgat on the 9 July 1920, “pillaged the houses of Greeks, and killed 60 Greeks and 20 Armenians.”[8]

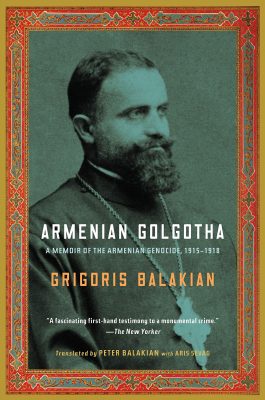

Grigoris Balakian: The Confessions of a Slayer Captain

The Armenian cleric Grigoris Palagian (Balakian) was one of the Armenian intellectuals arrested in Constantinople at the end of April 1915 and initially deported to Çankırı. From there he was further deported. In his memoirs, he describes in detail his conversation with Şükri, who as captain of the Yozgat gendarmerie was responsible for the massacre of Armenian deportees in the sancak of Yozgat. Şükri speaks freely about these crimes, as he firmly believes that Palagian and his convoy will also be massacred.

“‘Now it’s not a secret anymore; about 86,000 Armenians were massacred. We too were surprised, because the government didn’t know that there was such a great Armenian population in the province of Ankara. However this includes a few thousand other Armenians from surrounding provinces who were deported on these roads. They were put on this road so that we could cleanse them.’ (…)

‘Upon whose orders were the massacres of Armenians committed?’

‘The orders came from the Ittihad Central Committee and the Interior Ministry in Constantinople. This order was carried out most severely by [Mehmet] Kemal, kaymakam of Boghazliyan [Boğazlıyan] and vice-governor of Yozgat. When Kemal, a native of Van, heard that the Armenians had massacred all his family members at the time of the Van revolt, he sought revenge and massacred the women and children, together with the men.’ (…)

I asked Shukri Bey how the women and girls of Yozgat were massacred. (…)

‘There’s no reason to hide it… it was eight months ago, after all, and these stories are getting around… the news has even reached Europe. The German embassy was so upset that they rebuked our government, and orders then came from Constantinople telling us to cease the massacres. Nevertheless, after we had massacred all the males of the city of Yozgat – about eight thousand to nine thousand of them[9] in the valleys near these sites, it was the women’s turn.’ (…)

‘The caravans were always assigned to me because I was the police soldiers’ commander and familiar with this region. When this large caravan with about eighty police soldiers reached the three mills, in this valley four to five hours from town, I gave the order to the police-soldier officers to rest at this spot. I then ordered all the carriage and cart drivers to leave the families there and return to their villages. Then I had twenty-five to thirty midwives come in from town to begin a rigorous inspection. Every woman, girl, and boy was searched down to their underwear. We collected all the gold, silver, diamond jewelry, and other valuables, as well as the gold pieces sewn into the hems of their clothes. All these women, duped into thinking that they were going to join their husbands in Aleppo, had taken with them all their valuable and moveable possession, including their valuable rugs and carpets. The government’s pretense had worked beautifully. (…)

During the time we were searching the women, the government officials of Yozgat sent police soldiers to all the surrounding Turkish villages and in the name of holy jihad invited the Muslim population to participate in this sacred religious obligation.

Thus, when we arrived at the designated site, this mass of people was waiting. The government order was clear: all were to be massacred, and nobody was to be spared. Therefore, in order to prevent any escape attempt, and to thwart any secret attempts of sympathizers intent on freeing them, I had the eighty police soldiers encircle the hill, and I stationed guards at every probable site of escape or hiding.

Then I had the police soldiers announce to the people that whoever wished to select a virgin girl or young bride could do so immediately, on the condition of taking them as wives and not with the intention of rescuing them. Making a selection during the massacre was forbidden. Thus about two hundred-fifty girls and young brides were selected by the people and the police soldiers. (…)

It’s wartime, and bullets are expensive. So people grabbed whatever they could from their villages – axes, hatchets, scythes, sickles, clubs, hoes, pickaxes, shovels – and they did the killing accordingly.’(…)

The plunder of the clothes of these thousands of older and younger female martyrs (who were consecrated with eternal divinity) lasted four to five days. Then it was the turn of the dogs, wolves, and jackals, which picked up the scent of blood and came from all directions to complete the job started by the Turks. Left in the open air, the bodies then began to swell, rot, and decompose. When the Interior Minister Talaat himself suddenly arrived in Ankara (on the pretext of transporting cereals and legumes stored there to Constantinople, no less), he secretly visited Yozgat. Wishing to inspect the site to see how well his orders had been carried out, then to remove the traces of the crime, he had large ditches dug, and had the scattered, by now partially skeletonized remains of the wretched female martyrs collected and buried, imaging he could hereby also bury the black and bloody story of this great tragedy.

Not long afterward, when Talaat visited Berlin, the German Kaiser Wilhelm honored him with the black eagle insignia, an honor very rarely given to non-Germans. With this decoration, Talaat was elevated to the ranks of German nobility, as the Gambetta, Cavour, or Bismarck of the Ottoman Empire.”

Excerpted from: Balakian, Grigoris: Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1918. Translated by Peter Balakian with Aris Sevag. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, pp. 139-149