Around Lake Iznik (Askania Limne)

„Lying in the northern part of the sancak of Bursa, around Lake Iznik, the six Armenian villages in the kaza of Bazarköy constituted the biggest demographic concentration in the region. In 1910, a total of 22,209 Armenians lived here; their ancestors, who came from Agri, Arapkir, Palu, Harput, and Erzurum, settled in the area between 1592 and 1607.

To the northeast of Lake Iznik, Keramet had 1,215 inhabitants. Two hours further west lay Medz Norkiugh – Cedik Kariye for the Ottoman administration – with its 2,937 Armenians, almost all of whom earned their living either from the cultivation of grapes and olives or as craftsmen. Three kilometers further west, Michakiugh/Ortaköy had a population of 3,000. Çengiler, also in the immediate vicinity, was a large village of 5,000 inhabitants known for its silk workshops, which employed several hundred workers, and its 500 to 600 steam-driven wheels in the workshops of the village. Around 1914, the village exported more than 2,000 kilograms of raw silk annually to Marseille, Lyons, Milan, and London by way of a cooperative that local craftsmen had founded to secure supplies and promote sales. The 1,000 inhabitants of the village of Benli/Gürle, on the southwest shore of the lake, lived mainly from fishing. Finally, the village of Sölöz, two hours further south, boasted a population of 4,000.”[1]

“The entire region is extremely water rich. There were at one time thirty-eight hot springs near Keramet that emptied into Lake Iznik. The town of Yalova, near Keramet, had many hot springs, and so did the town of Kaplaga. (…)

Before 1915, there were a number of Armenian villages near the lake: Çengiler, Ortaköy, Yeniköy, Norkek, and Keramet on one side of the lake, and on the opposite side Bayni [Benli], Karsak, Gurla [Gürle], and Sölöz. Some distance away was the large city of Adabazar [Adapazarı] that had an Armenian population of twenty thousand, while the smaller towns of Orhangazi and Gemlik had large communities also. There were well over one hundred Armenian villages in the province of Bursa.”

Source: Ellen Sarkisian Chesnut: Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried; A Daughter Confronts the Armenian Genocide and Tells Her Father’s Story. Minneapolis: Two Harbors Press, 2014, p. 26

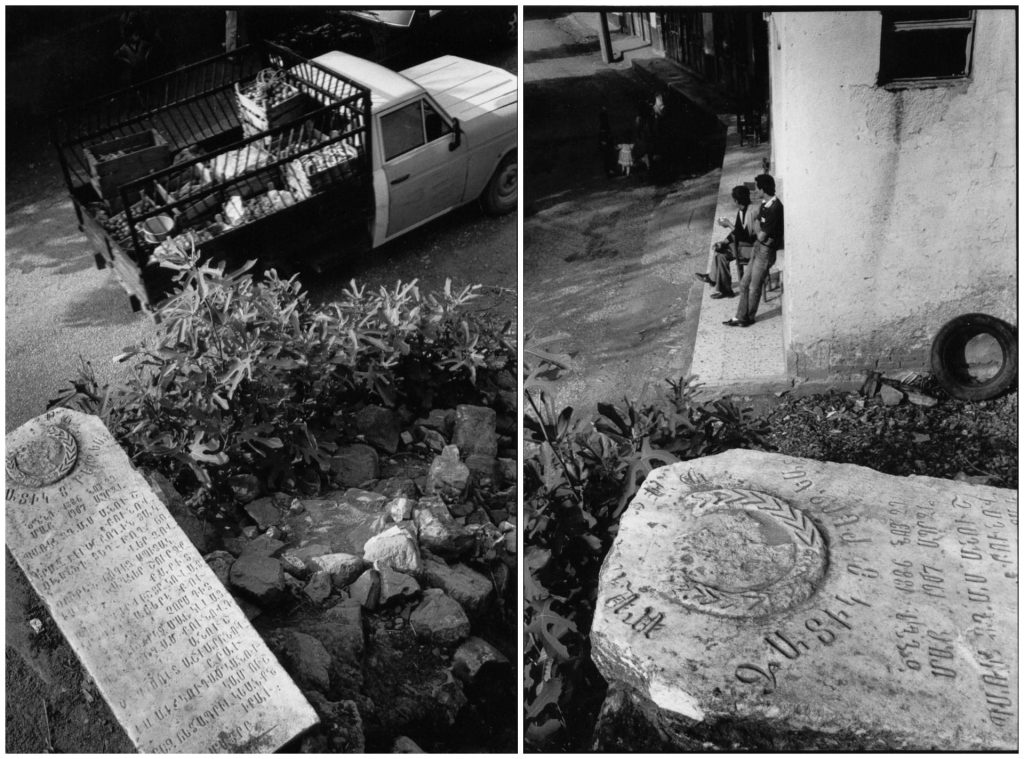

Keramet (Kaza Bazarköy): An Armenian village

Situated at the northern shore of the sweet-water Lake Ascania (Turkish: Iznik Gölü), the village was inhabited by approx. 1,500 Armenians and five Turkish families, who spoke fluent Armenian in the early 20th century. Keramet lies in a fertile plain, bounded by a range of hills. Besides olives, cultivated in and around Keramet, the villagers grew grapes, wheat, barley, oats, millet, bitter vetch, maize, sesame, flax, hemp, cotton, tobacco, kidney beans, broad beans, chickpeas, lentils, melon, watermelon, and chestnuts. Rose oil was extracted from the flower. The village had a winery and an olive oil processing facility.

In the village school all grade levels were taught. Resident Sarkis Mesrobian (1905-1995) recalled: “The girls were separated from the boys, even though we shared the same building. All of our teachers were men. We read and wrote in Ottoman Turkish (with Arabic letters). We learned to read and write in Armenian, too, but were not taught Armenian history. We also learned arithmetic. We had no doctors in the village; children came down with chicken pox and measles. We used herbs for treating all kinds of ailments. My father treated people who had bad burns with herbs.”[2]

In 1915, weeks before the Armenian deportations began, the Greeks of the Yalova Peninsula were warned by their Turkish neighbours that the “situation was tense” before a messenger from Constantinople officially announced the deportation order for the Armenians. The inhabitants of Keramet were deported in cattle wagons from the Mekece railway station (kaza Bilecik) to Adana; from there they walked under guard via Maskana (Meskeneh), Rakka, Dayr-az-Zor, Ras-ul-Ayn to Mossul. The then ten-year-old Sarkis remembered:

“I had trouble breathing, as the boxcar was very hot and stank. We were crammed in so tight behind the slatted bars of the boxcar. No water to drink! Two piles of straw: one at one end of our boxcar for the women and at the other end, a pile for the men to relieve themselves. Every couple of hours, when the train stopped, we’d pushed back the side doors of the cattle car and rush out into the fields, using them for toilets.

After about four days of traveling in this way, the train stopped abruptly. The guards opened the slatted doors of and en masse we were pushed forward by those back of us desperate to get off. We jumped into the unknown.”[3]

In the further course of the deportation, Sarkis lost almost his entire family; they had to leave his exhausted father behind on the route between Dayr-az-Zor and Ras-ul-Ayn, his mother starved to death in Mosul.

Failed Return

After the end of the war, in May 1919, the Armenian General Benevolent Union (AGBU) financed the return of surviving deportees to their homes. Sarkis also ventured back to Keramet. But out of once 1500 inhabitants, only 45 returned – too few to make a new start.

“I was back in my beloved Keramet, but I didn’t feel safe there at all. Everything was so different now, and for good reason: bandits, thieves, and murderers controlled all roads.. Boys like myself were particularly at risk of being stolen, tortured, raped and brutally murdered. We have already recorded three unfortunate deaths. Lawlessness was the order of the day.”[4]

This insecurity, particularly marked in the Yalova region, is explained by the collapse of the Ottoman administration, civil war-like conditions in a disintegrating state, the intervention of Turkish nationalist associations under Mustafa Kemal and the resulting interreligious and interethnic conflicts; the Yalova massacres of 1920 and 1921 were mainly perpetrated against Greeks. At the local level, the fate of the returnees to Keramet was decided by an act of retaliation on the part of Armenians from other places.

An excerpt from Hagop Nigogossian’s memoirs from 1958 describes the incident:

“At the end of September 1919, a group of thirty Armenians came to our village. These were young men who were seeking retaliation against the Turks for the deportations and atrocities committed during the war and who had nothing to lose because they had already lost everything. They arrived at night and needed a place to rest until the next day, when they planned to go to the very wealthy Turkish village of Boyaleja (now Boyalica). This Turkish village was approximately one-and-a-half hours away from Keramet. Their plan was to destroy that village.”

Memoirs of Hagop Nigogossian, written in 1958, quoted from: Ellen Sarkisian Chesnut: Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried; A Daughter Confronts the Armenian Genocide and Tells Her Father’s Story. Minneapolis: Two Harbors Press, 2014, p. 77

During the evening prayer, the avengers captured over 30 Turks in the mosque of Boyalica, 16 of whom they shot. As the perpetrators had previously stayed overnight in Keramet, but could not be found by the police, the male Armenians of Keramet paid the penance on behalf of the guilty: twelve Armenian residents of Kerament were arrested in early October 1919, half of them sentenced to life imprisonment. H. Nigogossian served more than ten years in an Istanbul prison and reports about the worst torture including rape.

For the Armenian returnees and the Greek population of the Yalova Peninsula, the genocide did not end in 1917 but in 1923. The surviving inhabitants of Keramet fled first to Gemlik, then via Thessaloniki and Rodosto (Tekırdağ) to Bulgaria.

A prominent Kerametsi: Archbishop Khoren Ashekian – Խորէն Աշըգեան (1842-1899; Armenian Patriarch at Constantinople, 1888-1894)

Khoren Ashekian was ordained priest in 1863 and made bishop in Holy Etchmiadzin in 1871 at the age of 32. He became the dean of the Armash Monastery the following year.

The accession of Khoren Ashekian to the patriarchate (as Khoren I, 1888-1894) immediately afterwards enabled the damage to be repaired rapidly, though. Because the Armash monastery had been directly attached to the patriarchate since 1866, Patriarch Khoren was able to fulfill his ambition to make it a major intellectual center, a “Venice of the Armenians in Turkey”, referring to the role this town had played since the 16th century in the development of Armenian printing and letters in Europe.

Khoren Ashekian was an educator who edited the periodical Huys (‘Hope’), author of the textbook ‘The Essence of Logic” and translator of a number of books into Armenian. He opened a boarding school in Armash in 1872, naming it Ghevordiants, and created the special curriculum. While in Armash, the bishop was able to order and bring printing equipment to Armash for the first time from Europe, thus expanding its publishing capabilities. The Ghevondiants school existed for 19 years.

The archbishop was elected patriarch of Constantinople in 1888, and the next year, upon the recommendation of Bishop Maghakia Ormanian, he endorsed the opening of the famous Seminary of Armash in 1889, giving his special Encyclical of the Establishment. The seminary lasted twenty-five years and offered the Armenian Church most worthy priests until its brutal closure by the Ottoman authorities during WWI.

In spring of 1894, two assassination attempts targeted the Armenian patriarch Khoren Ashekian, and the chairperson of the Armenian Political Assembly Maksudzade Simon Bey, respectively. In both cases, the assailants were partisans of the Hntchak Party, a socialist Armenian revolutionary organization established in 1887. Ashekian resigned from the office of the patriarch in 1894.

Sources: Ellen Sarkisian Chesnut: Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried; A Daughter Confronts the Armenian Genocide and Tells Her Father’s Story. Minneapolis: Two Harbors Press, 2014, p. 185; Union Internationale des Organisations Terre et Culture, https://www.collectif2015.org/en/100Monuments/Le-monastere-d-Armache-ou-de-la-Sainte-Mere-de-Dieu-Destructrice-du-Mal/