Toponym

The Greek placename Belokoma (Βηλοκώμα) appeared in the 1308 enactment of Georgios Pachymeris (1242-c. 1310), a Byzantine-Greek historian and philosopher, born in Nikaia. The place-name goes presumably back to one of the Serbian settlements established by Byzantine rulers in this region in the late 12th century (‘belo’ meaning ‘white’). The Greek version of the placename should have taken the form of Vilegüme (Tr: Veligöme). The Turkish version Bilecük goes back to the year 1484.[1] The Thrakian toponym was Agrilion.

Population

While most of the Armenian population was concentrated in the kaza’s capital town Bilecik, a small number of Armenians lived in the northern part of the Bilecik kaza: in Mekece, on the right bank of the Sakarya (Gr: Sanagarios), in Levke (Lefke; Osmaneli today), ten kilometer further south, and in Gölbazar (Golpazari) or Nor Kyugh (‘New Village’; pop. 500); further to the southwest lay the Armenian villages of Göldağ (pop. 2,200) and Decir Hanlar (pop. 2,500). Ten kilometers to the east, the village of Turkmen was exclusively Armenian (pop. 2,630), despite its name.

“In August 1915, these 13,110 people found themselves deported in the space of a few days.”[2]

Notes of General Thilo Julius Bernhard Wilhelm von Westernhagen (1853-1920), member of the Prussian General Staff

Correspondence

Constantinople, 2 October 1915

Haidar-Pascha – Biledjik [Bilecik]

Almost all of the Armenians from this area have disappeared. Entire villages are uninhabited. Some of the houses have been sealed, but they are completely empty. Furniture and similar objects were stored in depots, but seem to disappear from there.

The Armenian quarter in Ismid was burned down.

In individual villages only children, particularly girls, were left behind.

Adapazar is almost completely deserted; almost all the stores are closed. Craftsmen, shoemakers, tailors, etc., are missing.

Almost all the towns must do without doctors, pharmacists, etc.

The silk industry, particularly in the area around Geive [Geyve; TH], has been completely suspended; the spinning mills are closed; only a few Greeks are still working, but they are also being treated badly.

Farming was also mainly in the hands of the Armenians. The difference between Armenians and Turkish fields is unmistakable, i.e. almost nothing grows on the latter.

Biledjik [Bilecik] is a clean, small town with large houses; now, it is inhabited by only a few Turks.

I saw no acts of violence, but it is obvious that the people are given nothing to eat on the journey. The Armenians are sent by train to Konia and from there on foot, “in order,” as a Kaymakam said, “to establish a kingdom for themselves in the desert”.

The Turks themselves differ greatly in their judgement of this matter. The population is hardly involved. Some people say that only a few revolvers and hunting rifles (30-60) were found and the Armenians had had no revolutionary ambitions whatsoever, and the opportunity was merely used to get rid of them now that no other power can become involved.

Apart from the Russians, the greatest blame is placed on the Americans, because they incite the Armenians and also support them financially. The hatred against the Americans appeared to me to be greater than against any one of the warring countries. Robert College [Nahiye Bardizag] is described as being the centre of the entire movement.

I actually saw some Americans on the train who were coming from Anatolia.

The inner circle around the Grand Vizier is extremely chauvinistic; every non-Muslim is described as a “sales gens” [“filthy person”]; it was admitted to me that the Armenians needed to be exterminated to the last child, but it appears as if they wish the same for all other Christians.

“Turkey for the Turks” is a slogan: the Turks should do everything now. People complained that Turkish was not the language of business at the Anatolian Railway Company and that no Turks were employed.

The Caucasus, with a somewhat imprecise definition of its borders, and Egypt are to become Turkish. The military successes seem to have gone to people’s heads: they think they are doing everything and that they are Germany’s saviours. Even the ammunition is supposedly manufactured by the Turks.

However, a great many people frankly admit that the deportation of the Armenians is, and in particular will be, a tremendous disadvantage for the country, because all the work is carried out by the Armenians: silk, tobacco, fishing, all of the trades, hotels, restaurants, etc.; even Turkish officers asked me to do something to enable them to keep their Armenian soldiers, because the Turks do not work.

The Turk seems to be absolutely incapable of continuing to work where the Armenian has stopped. All of the fields lie uncultivated, hardly a store has been opened again, almost all of the villages appear to be dead.

Admiration for Germany is very great among the population. The people come together in the evenings and a Hodja reads from the newspaper; all of the German army leaders are well-known. I spoke a great deal with the people and also visited schools and hospitals and distributed books and illustrated magazines. It seems to me to be very important that Germans, especially officers, go everywhere and try to make friends with the population; the people are grateful for every word.

Would it not be possible to set up cinemas and show pictures of the war? Every village has a large hall. It would be a great success.

Economically, a great deal can be done with this country. Grain, tobacco, sheep farming, fruit as far as Ismid, from there onwards a great deal of silk.

Excellent forests near Adapazar and Boli, often also coal, e.g. near Boli.

The Geive basin is very fertile; for this reason, there is also a great deal of silkworm breeding there. There are rich ore deposits in the surrounding mountains: I have seen stones that contained a great deal of ore. Coal is also found there.

The Sakaria River can be used for shipping, transporting wood, etc., especially for mills. There is only one in Vesir-Han.

Source: http://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs-en/1915-10-02-DE-003?OpenDocument

The Greek Deportees from Kydonies (Κυδωνίες; Tr: Ayvali/Ayvalık) arriving in the Bursa Province (April/Mai 1917)

„I will not attempt to depict the pitiful spectacle presented these unfortunate persons. I can only say it was a jumble of large and small skeletons begging for pity. This group has been marching for forty-five days and is to march a good many days to come, inasmuch as it is destined to settle in Yeni-Chehir and Biledjik. They in vain implored to be allowed to stay here [in Bursa], if not permanently, at least for a few days in order to rest, because many of them cannot walk as a result of fatigue and hardships. Their sufferings on the way are truly incredible. Over 180 of them died on the way, their bodies being thrown into ditches; others, half dead, were left in the middle of the road, and women, after giving birth to children, abandoned their babies and followed the other wayfarers. I had the misfortune to follow closely from the beginning all the phases of the accursed persecution, but in no case have I seen a harder attitude on the part of the persecutors who were indeed utterly insensate. The number already here consists of 500 to 600 families, and others are coming every day; according to the information given by the latter, those that are to follow are more numerous than those who have already arrived, consisting of ten to thirteen thousand persons. In the village of Tahtali and Yailahdjik of the district of Broussa, 200 families have already been settled.”

“(…) The place where they are to settle is not known exactly, because the authorities take great care that the displacement of the Greeks be carried out as quietly as possible, but I was informed to-day by a Greek soldier (serving in the Turkish army) that a good many families from Cydonia are encamped in a plain about an hour’s distance from Broussa and that they begged him to notify me that those families which are on their way to Biledjik are dying from hunger and in need of speedy assistance.”

Source: Reports of the Hellenic Legation, April and May 1917, quoted from: Ion, Theodore P.; Brown, Caroll N. (Carroll Neidé): The Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey since the Beginning of the European War. New York: Pub. for the American-Hellenic Society by Oxfort University Press, American Section, 1918, p. 57f.

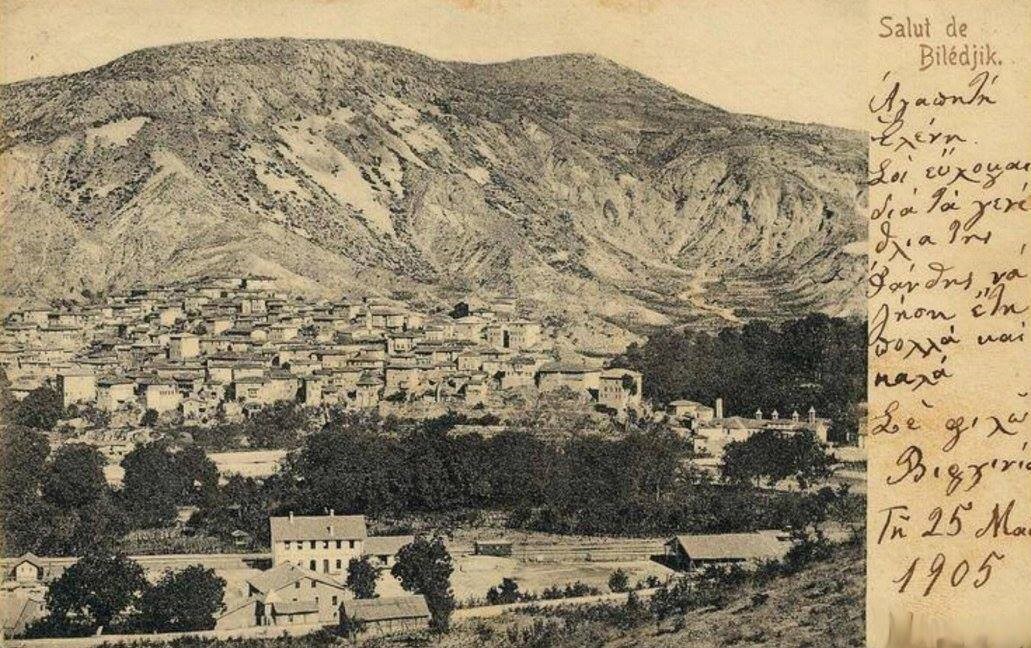

Bilecik Town

Located on a hillside on the left bank of the Karesı (Karası; Karasu) river, Bilecik had somewhat more than 10,000 residents in 1914; 4,080 of them were Armenians who lived in the Balipaşa neighborhood. Most were occupied in raising silkworms and spinning silk in the 17 sill-milks, almost of them Armenian owned.(4)

The Deportation of the Armenians from Bilecik and the Destruction of Its Armenian Quarter – An Eyewitness Testimony

A Mkhitarist monk, Hagop Pozbiyikian, who witnessed the events notes that he was in Bilecik on 16 August 1915, the date on which the notables and the auxiliary primate, Father Simon, were summoned by the mutasarrif Cemal Bey and told that they had to leave in three days. The monk observes that there were very few men in the town, since they had been mobilized; that, for a week, it had been impossible to travel outside the town; and that the Armenians of Bilecik had witnessed the passage of convoys of deportees from the west in a state that gave them some notion of what lay in store for them. Once the deportation order had been made public, the Armenian began to sell their furniture to their neighbors, who had flocked to buy what they could at extremely low prices. Scenes of the pillage of Armenian homes began to multiply from 17 August on, when the villagers from the environs came to take their part of the boot. On the 18 August (…) the Armenian church was full for the last service. The next morning, all the Armenians of Bilecik left the town in a single convoy bound for Eskişehir. The schoolchildren were invited to help demolish the Armenian quarter. (…) The pillage and the sacking of the Armenian quarter went on for ten days. Only the cathedral, which had been converted into a depot, and the homes of the few notables, occupied by government officials, escaped destruction. With the exception of a few Catholic families, Bilecik was emptied of its Armenian population.

Source: Father Y.P., Pilečiki Aġētė, 1915 [The Catastrophe of Bilecik, 1915], “Pazmaveb” 1921, pp. 177-119, quoted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 562f.