Toponym

The ancient name of the region, which includes the kazas of Gümüşhane and Torul, is Chaldia (Arm.: Xağdik [Xaltik], Խաղտիք); Byzantium’s Chaldia province (theme) emerged in the 9th century. The Greek name is widely used until the beginning of the 20th century; it is sometimes heard in Turkish. The name of the people who gave the country its name and has been famous for mining from a long time ago is called Khalyb- with the Georgian + ib plural in Homer and Xenophon, and Khaldi with the plural adjective suffix in Armenian + di in later writers.[1]

The name Argyro(u)poli(s) stems from two Greek words (Argyro = silver, and Polis = city). Other names used to describe the town were Gimiskhana (Γκιμισχανά), and Kiumushana (Κιουμουσχανά). The place name Gümüşhane is documented since 1665, replacing the briefer ‘Gümiş’ (‘Silver’), documented since the year 1333. During the Ottoman period, the Greek-speaking population was also using the name Gümüşhane (Γκιμισχανά and Κιουμουσχανά) but, in the first decades of 19th century, the hellenized form Argyró(u)polis was established.

History

The Ottoman sancak in which Argyroupolis was situated, comprised 37 mines of argentiferous lead and 6 copper mines. There is no evidence that these mines were in use during Byzantine times.

Around 840 A.D., the area was included in the new Roman (Byzantine) province of Chaldia (Χαλδία). It was later ruled by the Byzantine Empire of Trebizond.

During Ottoman years, the sancak of Gümüşhane fell under the administration successively of the Rum Province, Erzurum Province and Trebizond Province, and was divided into the four kazas Gümüşhane, Torul (capital city Ardasa), Şiran (Grk.: Cheriana), and Kelkit (Grk.: Keltik).

Hundreds of Pontian families who were forced out of their homes after the Russo-Turkish War (1829/30) from the wealthy mining communities of Argyroupolis (Gümüşhane). Fifty years of temporary dwelling in the areas of Mesudiye, Semen, Fatsa, Kotyora, and Akdağmadeni were to pass before they found a permanent home in 1880 in the areas of Onoriada (Bithynia) and particularly the regions of Karasu, Adapazarı, and Nikomedia (Izmit), which are approximately 75 to 100 kilometres from Constantinople.(2)

Population

The local residents of Gümüşhane region were Laz people, also called Chan (Tzan; by Georgians), i.e. Chald (Halt; by themselves). This reflects in the Greek toponym Tzánika.[3] Sultan Murad ΙΙΙ (1574–1595) appears to have granted extra privileges to the chief miners, thus attracting Greek Orthodox Christians. The town prospered and soon became a center of Hellenism. At the time, it had 60,000 residents. Its trade was increasing and the whole province of Chaldia was on the rise.

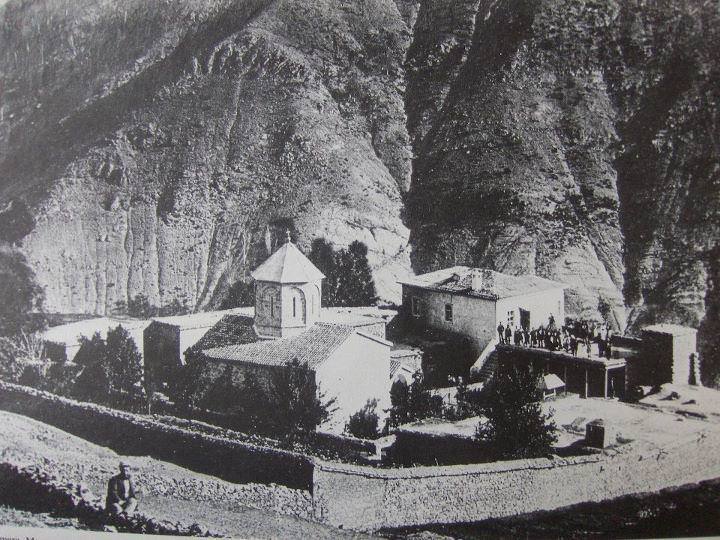

Ecclestically, the sancak belonged to the Greek-Orthodox Diocese of Chaldia, comprising 77,845 inhabitants in 145 communities.

By 1900, there was a total population of 119,968 in the sancak; of these, only 1.4% were Armenians (1,379 in the central kaza of Gümüşhane, 109 Armenians in the kaza of Kelkit, and 224 in the kaza Şiran.[4] According to Raymond Kévorkian, the sancak of Gümüşhane “had been largely emptied of its Armenian population after the Russo-Turkish War of 1828. In 1914, 1,817 Armenians were still living in the town of Gümüşhane. There were another 450 in Şeyran [Şiran], the seat of the kaza of same name, and 482 in Kelkit, the southernmost district in the sancak.”[5] The survey of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople gave the total Armenian population in the sancak with 2,749 in three localities, maintaining three churches and three (?) schools.[6]

In 1915, the mutessarif of the sancak of Gümüşhane, Abdülkadir Bey, who held his post from June 1915 to 16 January 1917, played a decisive role in the liquidation of the Armenians of his own district.[7]

Chaldia (Khaldia) / Χαλδία

Toponym and Geography

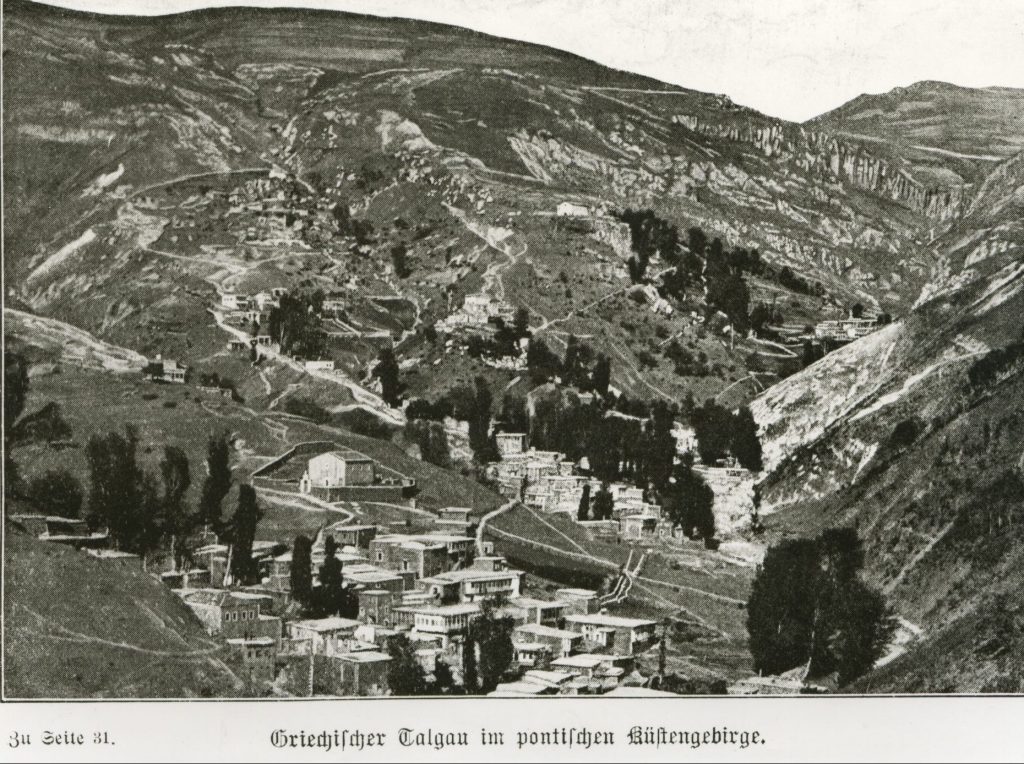

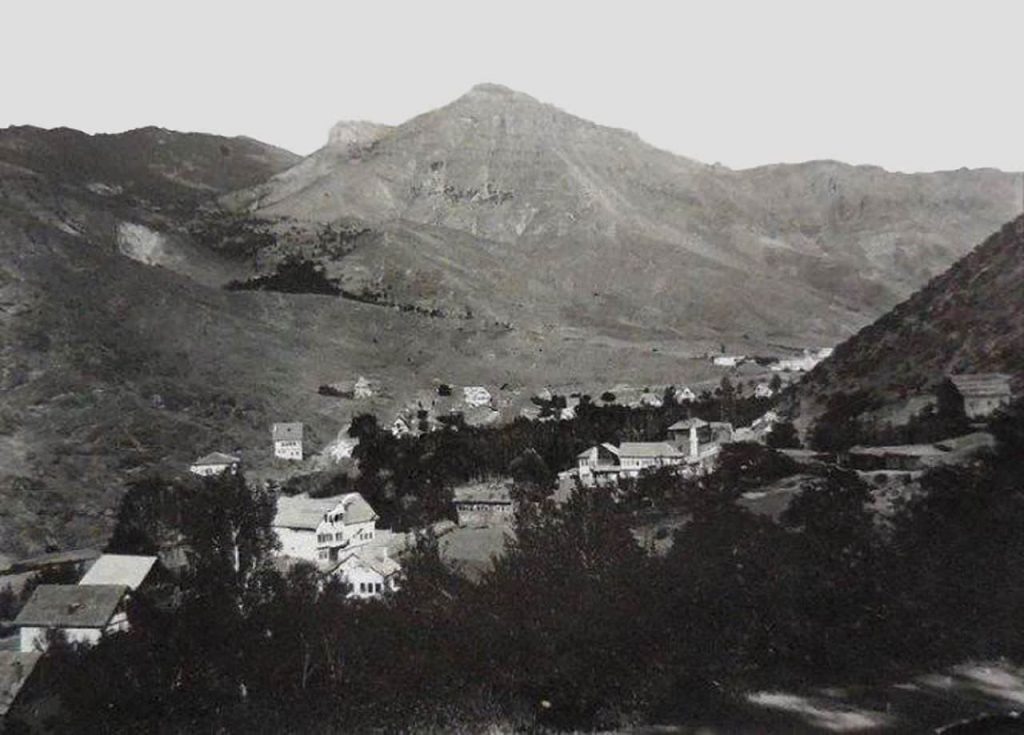

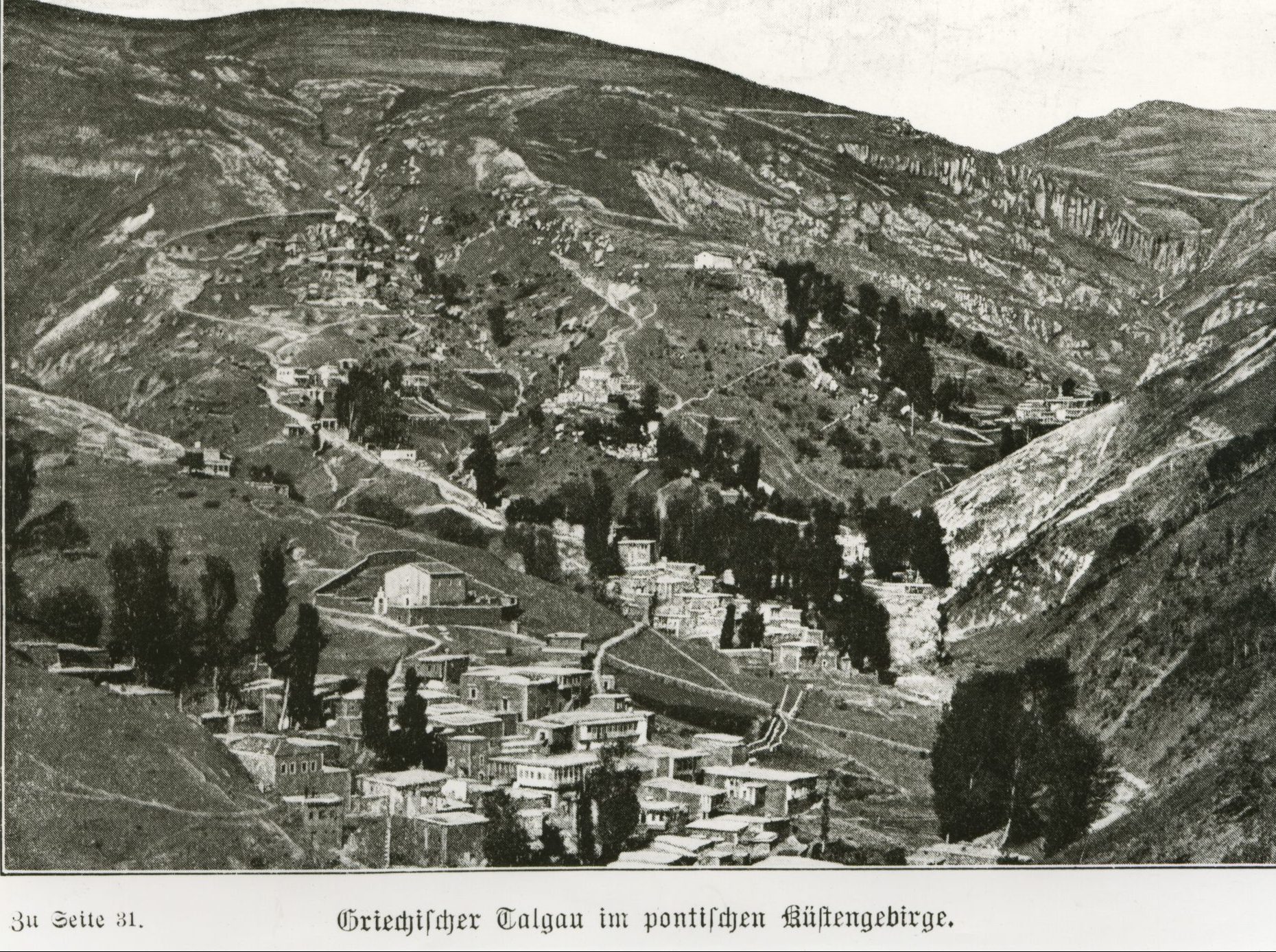

Initially, the name Chaldia was consigned to the highland around Argyroupolis (Gümüşhane), in northeast Anatolia, but in the middle Byzantine period, the name was extended to include the coastal areas, and thus the entire province around Trapezus (Trebizond, modern Trabzon). Forming the easternmost area of the Pontic Alps, Chaldia was bounded to the north by the Black Sea, to the east by Lazica, the westernmost part of Caucasian Iberia, to the south by Erzincan, Erzurum and what the Romans and Byzantines called Armenia Minor, and to the west by the western half of Pontus. Its main cities were the two ancient Greek colonies, Kerasus (Giresun) and Trapezus, situated in the coastal lowlands. The mountainous interior to the south, known as Mesochaldia (“Middle Chaldia”), was more sparsely inhabited and described by the 6th-century historian Procopius of Caesarea as “inaccessible”, but rich in mineral deposits, especially lead, but also silver and gold. The mines of the region gave the name Argyropolis (‘silver town’, modern Gümüşhane) to the principal settlement.

The British historian and scholar of Byzantine studies, Anthony Bryer (1937-2016) traces the origin of the toponym not to the Mesopotamian region Chaldea, but to the Urartian sun god Ḫaldi. Bryer notes at the time of his writing that a number of villages in the Of district were still known as ‘Halt’. Other scholars, however, reject this explanation, believing that the toponym derives from the ethnonym Chaldoi (or Chalybes). The Greek tribal name Χάλυψ (Chalyps) means ‘tempered iron, steel‘, a term that passed into Latin as chalybs, ‘steel’. More than an identifiable people or tribe, ‘Chalybes’ was a generic Greek term for ‘peoples of the Black Sea coast who trade in iron’.

History

As a historical region, located in mountainous interior of the eastern Black Sea, the toponym Chaldia was used throughout the Byzantine period and was established as a formal theme, known as the Theme of Chaldia (Greek: θέμα Χαλδίας, Thema Chaldias), by 840.

During the late Middle Ages, it formed the heartland of the empire of Trapezunt until its fall in 1461.

Until the territorial expansions in the 10th century in its eastern part, Chaldia marked the northeastern border of the Byzantine Empire. In the period 1091/1095-1098 and 1126-1140 the area was virtually independent of Constantinople. In the first of these periods the Seljuks separated Chaldia from the rest of the Byzantine territory; in the period 1091/95-1098, the region was reigned quasi-autonomously by Theodoros Gabras, who recaptured Trebizond from the Seljuks during the 1080s, and in the period 1126-1140 by his son, the dux Konstantinos Gabras. In 1140, Emperor John II Komnenos (r. 1118–1143) moved into Chaldia with the main Byzantine army in order to campaign against the Danishmend Turks. This display of force was enough to overawe Konstantinos Gabras, and the region came under direct imperial control once more.

After the dissolution of the Byzantine Empire during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Theme of Chaldia became part of the new Empire of Trebizond. This empire was, however, already in the 14th century practically reduced to its heartland of Chaldia. Thanks to its mountainous location, a small but powerful army and well thought-out diplomacy, the empire managed to survive longer than the Byzantine Empire before falling to the hands of the Ottoman Empire in 1461.

Destruction

Even before the First World War, the settlement of Muslim refugees (muhacirler) led to the flight of numerous Pontic Greeks from the hinterland to the coastal towns, especially to Trebizond: “Ethnic Greeks arriving daily from the interior of the Trapezounta prefecture inform us that, having severed their bonds with humanity altogether, the Young Turks have spread their lethal practices to the kazas [townships] of Argyroupolis [Gümüşhane] and Torul. The unfortunate ethnic Greeks who happen to live in those distant places have been overwhelmed by desperation; those who can leave their homeland in order to preserve the life and honor of their families, have done so”.[8]

The anti-Greek boycotts deprived the Christians of all they possessed and reduced them to absolute poverty. The organizer of the boycott was Cemal Azmi, Vali of Trebizond, under whose orders was the Governor (mutessarif) of Argyroupolis. General conscription was also among the causes conducive to the ruin of the Greek speaking communities, for the conscripts who supported their families were taken away from their homes. The Ottoman officers treated the Greek speaking population in a brutal way, making many Greek Orthodox Christians to desert.

In the region of Argyroupolis, the situation was particularly difficult because, as the teacher and eyewitness Dimitrios Apostolidis writes, uncontrolled requisition stripped Greeks of everything they owned: “The Christian shops have become like cellars from which the authorities help themselves to all kinds of goods, even luxurious and fashionable wares. At the same time, there was a law ordering the requisitioning of 25% of essential goods”.[9]

Ioakeimides, director of the Argyroupolis school in 1914-1915, filed a complaint that the government authorities had managed to turn the buildings requisitioned from the Chaldia ecclesiastical district, supposedly for use as hospitals, into extermination chambers for Pontian Greeks:

“I myself witnessed such a sad incident. Having been informed that the Girls’ School, which had been requisitioned as an infirmary, was full of sick people, I deemed it my Christian duty to pay a visit. All the rooms were packed to bursting; the air was foul, making it impossible to breathe. Ill and healthy were placed side by side. Although both categories were in need of fresh air, those who were not ill were shouting for the windows to be opened, while the sick complained of the cold. Confusion and upheaval ensued; it was a pathetic sight. There was no medical service to confront this great evil which had befallen the soldiers of the work battalions. In the condition they were in, those lodgings could only be compared to concentration camps for prisoners condemned to forced labour. They meant hell and death to the most productive age group of Greek Ottomans.”[10]

Ottoman and Russian Retreats, Massive Flight and Expulsions During World War One

The Russian advance gave rise to a fresh outburst of fanaticism against the Greek Orthodox population. Turkish villagers plundered their Christian neighbors. During the Ottoman retreat in 1916, the Turks again pillaged many Grecophone villages of the region. The inhabitants took to the mountains and their property was plundered. After the retreat of the Russians in 1918, the Turks returned and the few inhabitants that remained in these villages, were deprived of all resources and left to die of hunger.

Terrified by the news of re-occupation by the Turks, the Greek population in the provinces and cities alike abandoned their property and homes, and followed in the wake of the undisciplined, anarchic and often excessively violent Russian army. Teacher G. Chrimatopoulos, who personally witnessed those difficult days, describes the stance of the Argyroupolis (Gümüşhane) Greeks as follows:

“As soon as news of the Russian retreat circulated, many Greeks, who did not want to live under the heavy Turkish yoke, bade their beloved relatives and friends goodbye and fled to Russia. During those days, many hearts and souls were overwhelmed by intense patriotic emotions; people’s chests heaved with love and passion for their homeland. The streets were full of people weeping and sighing. Those who were leaving would kiss the ground of their beloved homeland, which they would never see again, with pain in their hearts.

‘Nothing is more beloved than one’s homeland; he who lives in happiness in his own homeland is truly blissful’. (Euripides)

The inns of Ardasa were filled with refugees from the villages around Ardasa and Argyroupolis, who would set off to Trapezounta, with Batum in Russia as their final destination.

Trapezounta became a kind of Babylon, with the multitude of refugees from the province and the departing Russian army units. However, since the boats in the port were reserved exclusively for the transport of soldiers, the unfortunate refugees were marooned in Trapezounta for over a month. How odd and fickle human nature is! The Turks, who only a little while ago appeared to be meek and peaceful; the Turks who proclaimed their respect and love for Christians, and used to address them—rather hypocritically—with the extolling word ‘efendim’ [‘Mylord’]; the Turks who wore European clothes and had enjoyed donations and benefactions on the part of their neighbours, the Greeks—it was as if by the touch of some magic wand, these same Turks suddenly turned into ferocious tigers (…).”[11]

Before Trebizond was ceded to the Turks, almost 30,000 Greeks from the surrounding villages fled there to seek refuge in Russia, where the situation was also bleak, because of civil war.[12] From 15 January to 1 March 45,000 Greeks from the Diocese of Chaldia, 4,862 from the Diocese of Rhodopolis, and 26,000 from the Diocese of Trebizond were displaced by the Turks and sent to Russia. An estimated total of 85,000 Greeks fled to Georgia and other areas of the previous Russian Empire.[13]

On 20 May 1919, Archimandrite Panaretos and Dr. K.A. Fotiadis, commissioned by the Central Pontian Union of Greeks of Ekaterinodar and a special recommendation from the Ecumenical Patriarch, visited the ecclesiastical regions of Pontos and recorded the situation in detail. The completion of their statistical record coincided with the arrival of Mustafa Kemal in Samsun. This document, which was conveyed to the Hellenic High Commissioner as well as to the chief of the Hellenic military mission in Constantinople, Colonel Katechakis, contains the following information about the deportations and expulsions that took place in the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Chaldia during WW1:

“(…) Prior to the war, the province [Diocese] of Chaldia-Kerasun [Giresun], which includes eighteen administrative sections boasted two cities, 14 towns, 266 villages, and a total Greek population of 167,450. Around 45,000 of these people, mostly from Argyroupolis [Gümüşhane], Kelkit and Cherianna [Şiran] were forced to seek refuge in Russia during the reoccupation, while more than 90,000 were relocated to the depths of Asia Minor, particularly those living on the coast after 1915. More than 80% of those exiled died of hunger during the expulsions, sufferings and beatings. Of these 10 were hanged, 85 shot by governmental agencies, and over 600 murdered by Turkish refugees. From the 72 Greek villages of the region none were saved; three quarters of the houses in the Greek villages around Argyroupolis, Kelkit and Cherianna are ruined.”[14]