History

Located on the eastern edge of the Cilician (Çukurova) plain in the foothills of the Amanos (Tr. Nur) Mountains, the gateway between Anatolia and the Middle East, Osmaniye is on the Silk Road, a place of strategic importance and has been a settlement for various civilizations including the Hittites, Persians, Eastern Romans and Armenians.

The Islamic presence in the area was first established by the Abbasid Caliph Harun Rashid, auxiliaries in his army being the first Turks to fight in Anatolia. They obviously took a shine to the place and following the Turkish victory over the Byzantines at Malazgirt in 1071 waves of Turkish conquest began. The Amanos Mountains were settled by the Ulaşlı tribe of the Turkmens.

The Ulaşlı remained the local power through into the period of the Ottoman Empire and were even involved in the Celali uprisings, during a period of uncertain Ottoman rule in the 17th century. Eventually, in 1865 the Ottoman general Derviş Paşa was charged with bringing law and order to Cilicia. He established his headquarters in the Osmaniye villages of Dereobası, Fakıuşağı, Akyar and brought the Ulaşlı down from the high mountains to the village of Hacıosmanlı. This eventually became the kaza of Osmaniye.

Destruction

1909

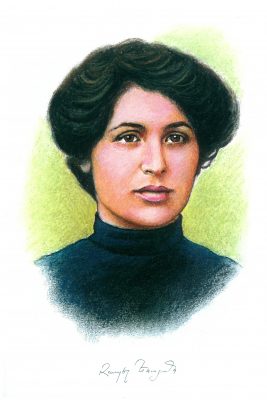

During her factfinding mission after the Adana massacres (April 1909), the writer Zapel (Zabel) Yesaian (Yessayan) also came to Osmaniye.

Zapel Yesaian: ‘There is no God now!’

“We had arrived in Osmaniye. (…) Osmaniye was silent, as if it were uninhabited. We heard nothing but twittering birds and clucking chickens. (…) At last, we reached the church: four charred walls and a floor carpeted with white ash. The unfortunes who had taken refuge there had all been burned alive. The floor was literally covered with small fragments of burned human bones. In the sun, they were a pale mother-of-pearl white; in the shadow of the walls, they took on a purplish tint. The people from Osmaniye told us that, in the dark of the night, a phorescent light sprang from these bits of bone and went fishtailing over the floor.

A cold shudder ran over us. I bent down and scooped up a handful of those holy relics. A handful of remains…charred fragments of a small white bone… What now gutted vitality, what now extinguished passions and enthusiasm do you represent, what longings and unrealized desires — but also what terror, and what terrible death agony.

Our eyes had no more tears to shed.

There were human traces on the walls as well: bloodstains marking a handprint, traces of blood that had spurred onto these walls from burst veins, as if from a fountain. They depicted, more eloquently than any description could, the last struggle of those who had fled to the church. It was atrocious: before dying, people must have trampled each other underfoot and climbed up on top of each other. They must have tried to flee for their lives by heaving themselves up onto piles of the wounded and dying, for we saw the marks many hands located much higher on the wall than a person could reach, and sometimes, in the arabesque painted by burst veins, the trace of a whole arm. And there, on the wall of that church in Osmaniye, we also discovered an inscription recorded in blood. (…) The teacher accompanying us thought that the handwriting was that of another teacher from Hadjin [Hacin], the one refugee in the church who had had a gun. It was probably that same teacher who had emptied the one firearm in Osmaniye from the church window.

The inscription was, precisely, near what was left of the window. Albeit short and inchoate, it was singularly suggestive. (…) The inscription began this way: ‘The events began on April 3.’ At that point, they had still had hope of surviving, hope that the inscription would be continued. But then the enemy advanced as far as the church door: the rifles roared, the smoke became thick enough to asphyxiate them, and death began to settle over them like an endless night. The poor village teacher, who had very little time left in which to express his desire for sunlight and life and brightness, had found the age-old word, the one, collective word of a race betrayed and delivered up the forces of darkness; and he had written, under the first line, ‘Light! Light! Light!’

But the hellish scene was unfolding as he wrote: the walls protecting the throng exploded, split open, and the flames, the flames, the flames of that conflagration, slithered in like snakes, multiplied, fanned out, reared up, and darted in every direction, amid the cries, the screams, the wails, the shouts of pain and fright of terrified human beings (…). It was then that the teacher, turning his eyes from the unpitying Virgin and the impotent Christ on the cross, wrote his third and last sentence: ‘There is no God now!’”

Excerpted from: Yessayan, Zabel: In the Ruins: The 1909 Masscres of Armenians in Adana, Turkey. Boston, MA: Armenian International Women’s Association, 2016, pp. 150-160

1915

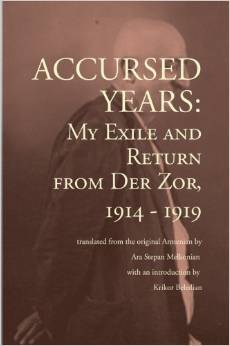

In 1915, the town and kaza Osmaniye were a frequent transit region for Armenian deportees. The journalist and writer Yervand Otian (1869-1926), who was a deportee himself, described their misery in his memoirs:

“We stayed on Osmanieh for about ten days. Then we started our journey by carriage to Islahieh, which was two days away. On this journey we saw the indescribable misery of the caravans of deportees. Thousands of women, girls and children, bent under heavy loads, broken and racked with pain walked along undulating, stony and muddy roads, crying and lamenting. Bodies could be seen here and there, ravaged by birds of prey, dogs and hyenas. Sick people were groaning without help under the trees. Newborn children abandoned, crying with hunger. Bodies so badly buried that arms and legs stuck out of the ground… scenes from hell that Dante could have imagined. Small children, lost or abandoned, would cry ‘Mummy, mummy’, but received no answer. And we could see that unbelievable calamity, that dreadful horror, without being able to help in any way, without being able to offer any comfort.”[1]