Armenian Population of the kaza of Ankara

On the eve of the First World War, there lived 11,319 Armenians in two localities of the kaza of Angora, maintaining 72 churches and 15 schools with an enrolment of 2,000 pupils.[1]

History: Galatian republic, Roman province

“Its ancient name of Galatia came from the Gauls who passed through Asia in the year 278 BC, and founded a republic there. Defeated later by the Romans, they preserved at first a kind of independence, and were governed according to their own laws under an appearance of republican form. After the defeat of Mithridate, Galatia, which had been conquered by the king of Pontus, returned under the Roman domination; but then its government changed form; a Galatian prince, Déjotare, was named king. His secretary Amyntas having succeeded him, reigned twelve years; then Galatia was reduced by Augustus in Roman province, in the year 25 before the Christian era.

During several centuries Galatia, counted among the richest provinces of the empire, saw its prosperity grow in peace, but soon, it suffered again all the evils of the war, conquered all in turn by Persians, by the Arabs, by the Turkish Seljuk Sultans, and finally by the Latins, who remained eighteen years in possession of the city of Angora, where they built several churches and repaired the castle.”[2]

Angora Goats

“These skins, either simply washed or dyed in the country itself with solid and vivid colors, are used to make elegant and soft foot mats for bedspreads and warm and comfortable saddle blankets. The wool of the fleeces is used to make magnificent fabrics, as well as the shiny hair of Angora goats, which is often mixed for this purpose; the fabrics obtained with the help of such a mixture combine the shine and fineness of goat hair fabrics with the thickness and suppleness of cloth.“[3]

City of Ancyra/Ankara

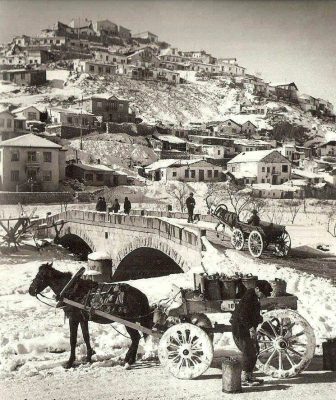

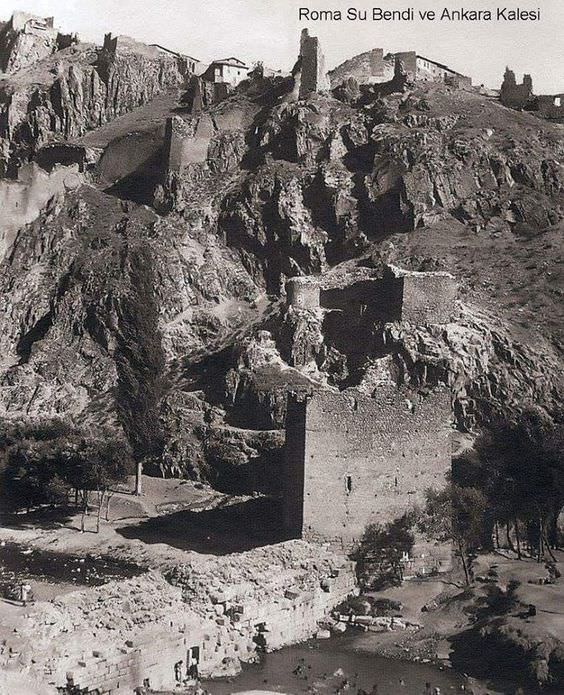

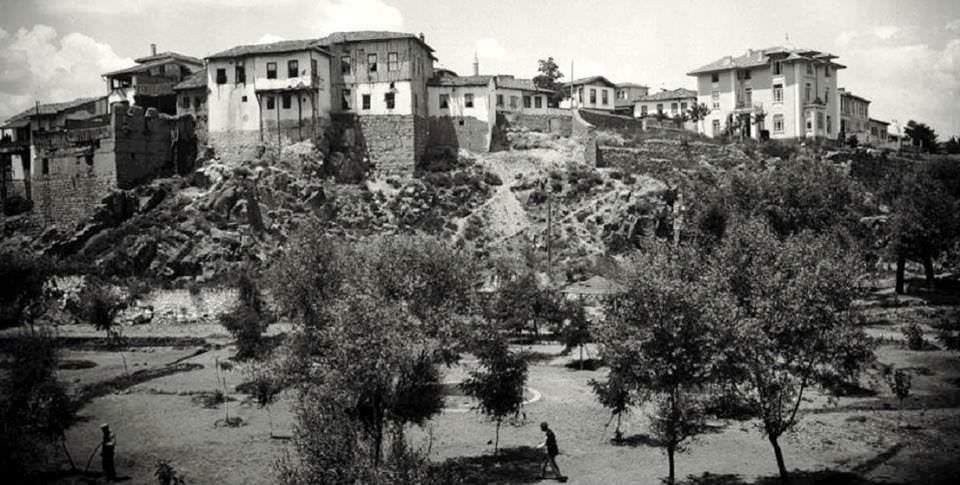

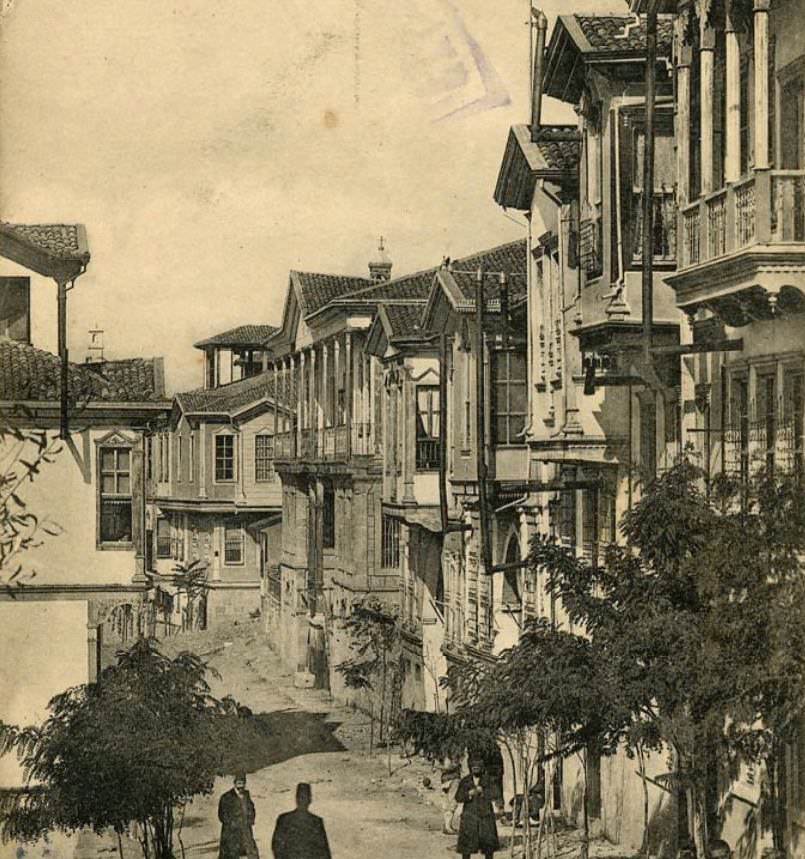

“Angora, the ancient Ancyre, once the capital of the Gallic kings, is built on a plateau situated at a thousand meters above sea level. Its surroundings are fertile in cereals; but deprived of trees. The city is dominated by a fortified castle which is falling into ruins, and whose walls contain several ancient sculptures. A great number of historically important inscriptions have been discovered in this city, among them the famous testament of Augustus.”[4]

After Ankara became the capital of the newly founded Republic of Turkey, new development divided the city into an old section, called Ulus, and a new one, called Yenişehir. Ancient buildings reflecting Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman history and narrow winding streets mark the old section.

Population

“The population of Angora is composed of Muslims, Greeks, Armenians and a small number of Catholics belonging mostly to the latter nation [Trk.: Katolik millet].”[5] Prior to World War I, the town had a British consulate and a population of around 28,000, roughly 1⁄3 of whom were Christians.[6]

Destruction

“Towards the end of 1892, Armenian massacres began on a large scale. With these, Sultan Abdul Hamid responded each time to the insistence of the [six] Powers for the final introduction of reforms. In January 1893 there were massacres in Kayseri and Mersiwan [Marsovan], in June a so-called ‘treason trial‘ in Angora [Ankara] with the execution of five convicts.” [7]

“The fight against Christianity, however, was mainly served by the forced conversions to Islam and the forced circumcisions of Christian boys (in Ankara, for example, a hundred mostly Catholic Christian boys were forcibly circumcised on the sultan’s birthday). Of course, there can never be any question of ‘voluntariness’ in the conversions, since even the crowds of Armenians who declared themselves ready to accept the ‘true faith’ only did so in order to possibly spare their wives and children the worst, and in the hope of being able to return to Christianity later.”[8]

In his memoirs, written close to the event, the former U.S. ambassador to Constantinople, Henry Morgenthau, wrote: “At Angora all Armenian men from fifteen to seventy were arrested, bound together in groups of four, and sent on the road on the direction of Caesarea. When they had travelled five or six hours and had reached a secluded valley, a mob of Turkish peasants fell upon them with clubs, hammers, axes, scythes, spades, and saws. Such instruments not only caused more agonizing deaths than guns and pistols, but, as the Turks themselves boasted, they were more economical, since they did not involve the waste of powder and shell. In this way they exterminated the whole male population of Angora, including all its men of wealth and breeding, and their bodies, horribly mutilated, were left in the valley, where they were devoured by wild beasts. After completing this destruction, the peasants and gendarmes gathered in the local tavern, comparing nots and boasting of the number of ‘giaours’ that each had slain.”(9)

The facts of this destruction are confirmed in other accounts: “At the end of July [1915], all male Gregorian [Apostolics] Armenians between the ages of 15 and 70, with the exception of a few old men, were deported from Angora. They were surrounded six to seven hours beyond the town at the village of Beiham Bogazı by the Turkish gangs that had been ordered there and killed with shovels, hammers, axes and sickles after many had their noses and ears cut off and eyes gouged out. The number of victims was 500, and the corpses were left lying around, polluting the whole valley.

After another two weeks, the male Catholic Armenians began to be arrested and were forced to leave the city in two detachments, one after the other. The first squad was 800 strong, among them the clergy, the second numbered 700. They had to march ten to twelve hours a day in the direction of Kayseri and had neither bread nor money. It is not known where they ended up.

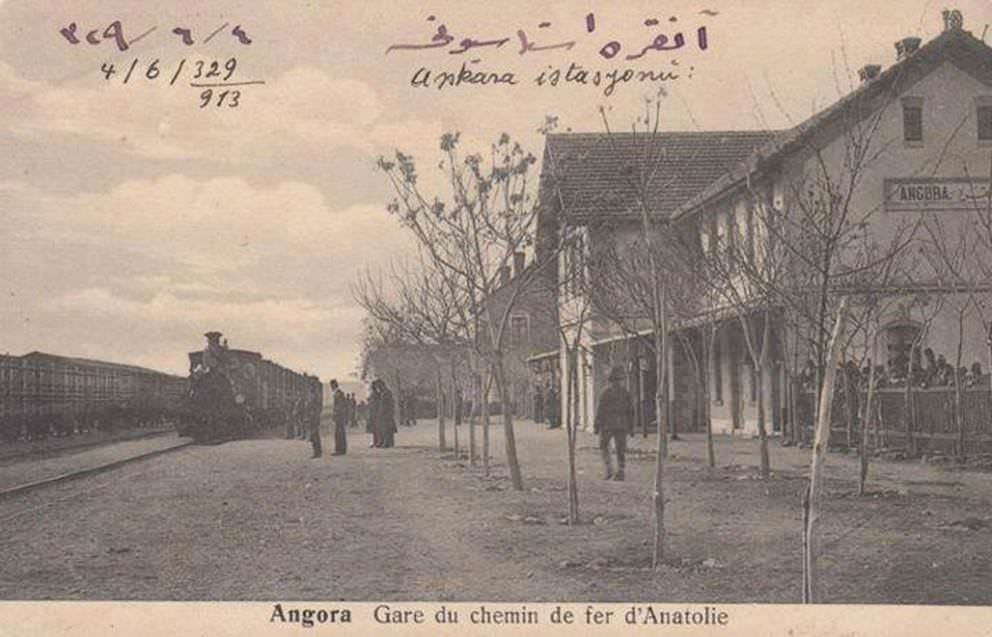

The third caravan consisted of the women and children of the city, to whom the münadi (that is the town crier) announced that they had to be at the station within two hours. In their haste, they could take only a few items of clothing, etc., with them. At the station they were locked up in a granary for four to five days, suffering from hunger and cold, and exposed to the lusts of the gendarmes. When it was thought that they had worn down, it was made known that all who would accept Islam could stay behind. Those who agreed to do so were allowed to return to the city. There were about 100 families. They had to sign a document stating that they had voluntarily converted to Islam and were distributed to Mohammedan families. The rest were taken by train to Eskişehir and from there to Konya. Armenian soldiers working on the railroad were also told to embrace Islam. Many did; those who refused were killed. (…)”[10]

“On September 17 [1915], with a final batch of 550 Armenians awaiting departure in Ankara’s train station, Atif reported his mission accomplished. ‘Angora now is a dead town,’ Stepan Semoukhine—a steward of the Russian Embassy, who had been exiled to Ankara with 129 other Russian Armenians—observed in November. ‘All goods belonging to Armenians are sold at auction. At six o’clock in the evening everything is dreary and mournful and even the Turkish families are grasped by fear.’”(11)

In a letter of the Armenian Catholic Patriarch Tertsian XIII to the German Embassy in Constantinople of 2 September 1915, it says about Ankara and the situation of the Armenian Catholics there:

“From reliable sources it is reported the complete evacuation of Angora, where only women would remain, who would now be forced to marry Muslims. About six thousand men, the priests (about thirty) and prayer sisters (about forty), together with their bishop Mrg. Grégoire Bakaban were shot on their deportation routes.“[12]