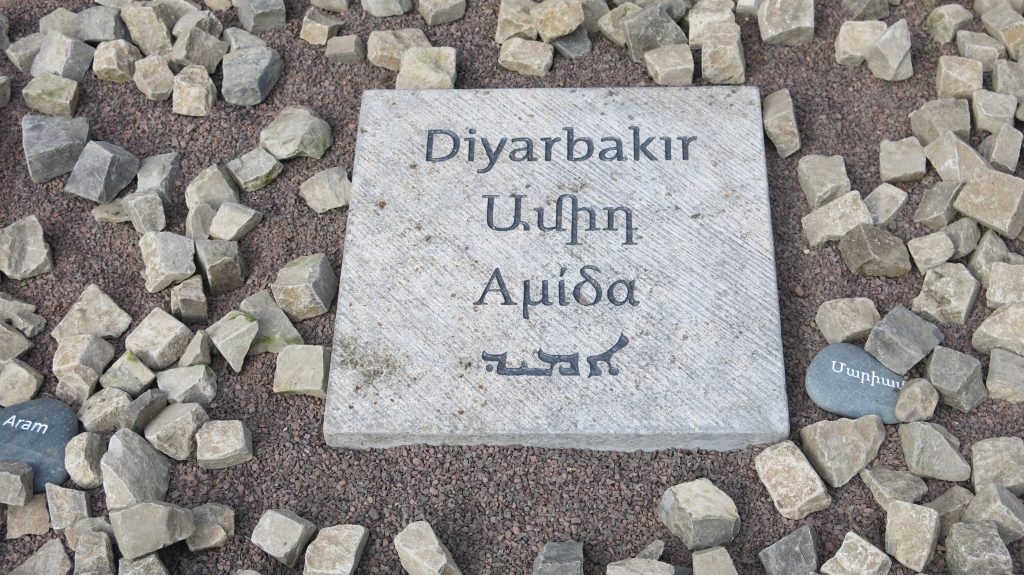

Comprising the six kazas Diyarbekir, Siverek, Derik (Aramean: Dêrike ܖܪܝܟܐ), Silvan (Aramean: ܡܝܦܪܩܝܛ Mîyafariqîn), Beşiri (Arm.: Chernik – Չերնիկ) and Lice, the sancak Diyarbekir was the central administrative unit of the province of same name.

Massacres and Deportations – ‘much more efficient and sophisticated’ than in other provinces

“In the first two weeks of June, Armenian men in the sancakof Diyarbekir were systematically rounded up and taken daily in groups of 100 and 150 to the Mardin gate or the road to Gözle (today’s Gözalan), where their throats were slit. A group of 1,000 men assigned to do maintenance work or administer military requisitions was also liquidated in similar condition.

Once the systematic elimination of the men had been completed, Dr. [Mehmet] Reşid worked out a method of liquidating the remaining population that proved much more sophisticated and efficient than those utilized by some of his counterparts in other provinces. Armenian witnesses noted that, every morning in the latter half of June, the colonel of the ‘militia’, Yasinzade Şevkı, accompanied by two other men, surrounded around 100 Christian homes in Dyarbekir and subjected them to methodical ‘house searches’. Guards prevented the occupants from leaving their homes until nightfall; at a predetermined hour, the vehicles used for military requisitions arrived at the designated houses and the 100 families living in them were loaded up and led from Dyarbekir in remarkably orderly fashion. This system had the advantage of forestalling disturbances in the city and leaving members of the other Christian confessions with the hope that they themselves would be spared. (…)

The first group, deported by way of the road to Mardin, comprised the women and children of the leading families of Dyarbekir, the Kazanians, the Trpanjians, the Yegenians, and the Handanians; they were promised that they would be reunited with the male heads of their households. Members of the richest families were separated from the rest of the convoy and detained in a village, Alipunar, south of the city. They were not allowed to leave until they had revealed where they had hidden their valuables. They were then taken to a place nearby, where their throats were cut. The other members of the caravan, 510 women and children were killed and thrown into the underground cisterns of Dara – vestiges of the Byzantine period located on the road to Cezire.

The next convoys were sent in one of two directions – southwest, toward Karabahçe, Severek and Urfa, or due south, toward Mardin, Dara, Ras-ul-Ayn, Nisibin, and Der-Zor. It seems that Kozandere, a place located one hour’s distance south of Dyarbekir next the village of Çarakılı, was the principal slaughterhouse on the second of these two trajectories. Kurds from the region and squadrons of çetes of the Special Organization were permanently stationed near the killing field, which went into operation with the second convoy of deportees from Dyarbekir. The massacre of these Armenians was bound up with a propaganda campaign orchestrated by Reşid, but no doubt ordered by Istanbul. Kozandere served as the stage for a macabre spectacle: the corpses of the Armenians tortured and killed there were dressed in Muslim costume, capped with turbans, and photographed. The pictures were then reproduced and widely distributed, first in Dyarbekir, later in Istanbul, and even Germany. They were supposed to show victims of atrocities committed by the Armenian ‘insurgents’, ‘in order to incite the population against the Armenians.’ (…)

Another killing field was located at the east, in the Bigutlan gorge, between the villages of Şeytan Deresi and Kaynağ. This spot, controlled by members of the Kurdish Tirkan tribe, is supposed to have seen the massacre of 80,000 deportees. We do not know, however, whether the victims were Armenians from other vilayets or Christians from kazas north of Dyarbekir. The second hypothesis seems more likely.

The majority of deportees were massacred well before they reached the place to which they were officially being deported. (…) Those who reached Ras ul-Ayn were dispatched by the Circassians of this small town, who plaited a rope 25 yards with the hair of young women whom they had killed. They sent it as a present to their commander from the Caucasus, the parliamentary deputy Pirincizade [Pirinççioğlu] Feyzi.

A few hundred Syriacs, both Orthodox and Catholic, were also deported from Dyarbekir, together with all the clergymen of these two communities. According to Father Jacques Rhétoré, more than 300 Armenian families in the city converted to Islam, together with a few Catholic Syriac households. (…)

Around 400 children between the ages of one and three were rounded up and initially placed in various institutions, notably the former Protestant school. It seems, however, that such measures, which were supposed to make it possible to educate these children in conformity with the Ittihad’s canons, remained in effect for only a short time. In the fall [of 1915] these children were deported in two convoys. Those in the first were thrown off the old bridge spanning the Tigris near the exit from Dyarbekir. Those in the second were sent to Karabaş, one hour from the city, where they were sliced down the middle and fed to dogs in the vicinity.”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, pp. 363-365

“In the massacres at Diyarbakir, Urfa, Kharput, Mardin and Midyat, the population faces a ‘literal deluge of blood’ and the villages were totally destroyed. Joel E. Warda lays the prime responsibility with the regular Turkish troops who slaughtered the Assyrians. Eighty-six Syriac Orthodox churches and fourteen monasteries were razed to the ground and 186 priests were killed.”[1]