Population

The kaza of Derik had in 1914 an Armenian population of 1,782. Of these, 1,250 lived in the administrative seat of the kaza, the others in the town of Bayraklı (Arm.: Bairuk) in half an hour distance from the town of Derik. They maintained two churches, one monastery and one school for 50 children.(1)

Derik Town

Derik was founded between 1390 and 1400 and lies 780 m above sea level. There are many Christian churches in the district.

Agha Petros listed 500 Syriac or Chaldean inhabitants; Father Joseph Tfinkdji stated that the Chaldean congregation numbered 40.[2] “(…) on August 11, 1915, the entire Christian population, which included both Syriacs and Armenians, totaling more than 1,000 persons, was massacred. Armalto stated that before the masscres the town was populated with 250 Armenians, Syriac, and Protestant families.”[3]

Today Kurds and Turks live in Derik.

Town of Viranşehir / Tella

Toponym

In Late Antiquity, the town was known as Constantina or Constantia (Grk.: Κωνσταντίνη) by the Romans and Byzantines, and Tella by the local Syriac population.

History

According to the Byzantine historian John Malalas, the city was built by the Roman Emperor Constantine I on the site of former Maximianopolis, which had been destroyed by a Persian attack and an earthquake. During the next two centuries, it was an important location in the Roman and Byzantine Near East, playing a crucial role in the Roman–Persian Wars of the 6th century as the seat of the dux Mesopotamiae (363–540). It was also a bishopric, suffragan of Edessa. Jacob Baradaeus (Mor Ya’cub Burdono; Baradai) was born near the city and was a monk in a nearby monastery. The city was captured by the Arabs in 639.

The city became the base for the Ottoman statesman of Kurdish origin Ibrahim Pasha, leader of the Kurdish Milan tribe, in the late nineteenth century. Beginning in 1891, Ibrahim Pasha led several regiments of the state-sponsored tribal light cavalries known as the Hamidiye Brigades. He enjoyed the favor of Sultan Abdül Hamid II, and also extended protection to local Christian populations, with some 600 families taking up residence in the district by the early 1900s. The British spy and diplomat Captain Mark Sykes claimed that Ibrahim Pasha had also saved some 10,000 Christians in the midst of the massacres of the 1890s.

Population

1,339 Armenians and “at least as many Syriacs belonging to different denominations”, lived in the town of Viranşehir.[4] “Living in isolation in an essentially Kurdish environment, the Christians of Tella (the Syriac name for the little town) were first and foremost craftsmen and merchants, who were rarely natives of the town.”[5]

Destruction

“The first events of note occurred on 1 and 2 May: the Armenian and Syriac Catholic churches were subjected to police searches. (…) it would seem that they were carried out against the will of the kaymakam, Ibrahim Halil, who had been in office since 29 February 1913. On 2 May 1915, he was replaced by Cemal Bey, very certainly on the instigation of Dr. Reşid. From then on, as elsewhere, one event followed hard on the heels of the last. On 13 May, the Armenian and Catholic Syriac notables were arrested and accused of belonging to a revolutionary committee. On 18 May, a second group of men was apprehended and imprisoned. On 28 May, the first group of notables was executed. On 7 June, ‘Circassians’ (…) proceeded to arrest all males between 12 and 70, a total of 470 people. On 11 June, at dawn, these 470 men were taken under guard to the nearby village of Hafdemari and put to death. The same day, part of the remaining Armenian population was rounded up, taken to the caves of the outlying area and massacred there. On 14 June, the same fate befell a second convoy made up by women. On 16 June, the third and last convoy was set out for Ras ul-Ayn, which a few survivors actually reached. (…) The property of the Catholic and Orthodox Syriacs (…) was systematically looted, but the Syriacs were not affected by the June 1915 massacres. On the testimony of Father Armalto, at least some of them were expelled and sent to Mardin, where ‘men, women and children’ arrived on 25 August. Thus, the treatment reserved for the Syriacs differed somewhat from that inflicted on the Armenians: two months after the Armenians, they were deported as families and assembled in administrative centers such as Mardin. Though stripped of their belongings, they were not methodically liquidated but abandoned to their fate without means of support. Let us note in passing that this ‘soft’ method would be utilized by the Kemalists from 1923 in order to cleanse the region of Diyarbekir of its last Christians and induce to leave for Syria, then under French mandate.”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 366

In an estimate presented at the Paris Peace Conference (1919), the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate put the number of massacred Syriac Orthodox Christians in the kaza Derik at 350. This apparently did not refer to the city and its surroundings of Viranşehir, where the Patriarchate estimated that 16 villages had been destroyed and 1,928 Syriac Orthodox Christians massacred.[6]

Mariam Akhoyan (born 1909, Derik): Testimony

„Before the massacre only Armenians lived on the village of Derik, Merdin [Mardin],[7] and they spoke only Armenian. There was a priest, Ter-Petros. The Turks[8] made him go on four feet: they rode him like a donkey; they pierced his back and neck with knives. He cried out: ‘Christ, save us!’

The Turks became furious and said: ‘Call your Christ, let him come and save you!’ Our old family name was Papoghlu (Son of Priest – Turk.). We were very religious. That priest Ter-Petros was from our ancestral house. We were a much respected family, but we suffered much.

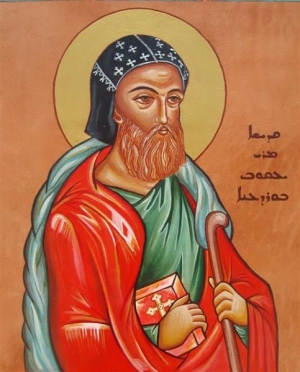

Our village Derik was in Merdin. There were five churches there – Assyrian, Armenian, Armenian Catholic, Protestant and St. George. There were paintings on the walls of St. George, the bells tolled.

When the massacre started, we were in our neighbor’s house. The askyars [Trk: askerler – soldiers] came to take father away; mother fell on him and began to cry. The askyars threw mother aside and took father to the army. And there he died.

They took me to a Turkish village. The elders would speak about the fact that the Turks were slaughtering Armenians and abducting girls. I was small, but I was intelligent enough to understand. I was clever: I used to rub mud on my face; I kept my feet and clothes dirty, so that they would not like me and take me. They said that they put stones on the bellies of pregnant women; then they stood on them, so that the child inside would die.

Later, mother came and found me in the Turkish village. Mother lived till the age of one hundred. She always used to say: ‘If they have had the possibility, they would take out my inner flame and they would hand it to me. That flame had entered our blood and marrow of our children.’ My poor mother, up to the end of her life, wore only black. She used to say: ‘If a Turk comes to your house, wash the steps and the door with soap water. If they give you an apple, make a hole in your pocket and throw it out. If they come, board up your house for they’ll take away either your money or your honor.’ Mother always had that fear in her heart; she feared that the Turks would kidnap her children.

There were three schools in Derik, but mother did not want her granddaughter to go to school. She hard hardly finished her elementary school and had just started the secondary school, when mother took her school-satchel and tore it up. She did that because she was afraid that the Turks would do her harm. At last, we came here [to Istanbul]. My grandson, Gevorg, and his brother are choristers in the churches of Samatia [Hasköy] and Gnali islands. Here they go to school. The Armenian school here won’t accept your child if he isn’t baptized.

Every morning, every evening daily I pray fifty times:

‘Oh, God deliver us completely,

Lest the Armenian Christian

Should fall into the hands of Turks.

Jesus Christ saved us:

He is our faith.’

When we came to Istanbul, we began kissing the walls and the ground of the church. As our village was very religious, we fasted at Lent…

Our Derik St. George Church had six keys: three of them turn this way, three of them turned the other way; the church bell used to ring. Now, not a single Armenian church is left there.”

Quoted from: Savzlian, Verjiné: The Armenian Genocide: Testimonies of the Eyewitness Survivors. Yerevan: “Gitoutyoun” Publishing House of NAS RA, 2011, p. 291f.