Toponym

The toponym originates from the Assyrian placename Marqas. Maraş (Armenian: Մարաշ – Marash; since 1973: Kahramanmaraş) was historically known as Germanicea (Grk.: Γερμανίκεια) Caesarea in the time of the Roman and Byzantine empires, probably after Germanicus Julius Caesar. The Turkish toponym attained the prefix ‘kahraman’ (meaning ‘hero’, ‘brave’) to commemorate the Battle of Marash.

Armenian Population

According to the census of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 32,844 Armenians in 23 localities of the kaza of Maraş. They maintained 20 churches, two monasteries and 23 schools for 1,629 pupils.[1]

City of Maraş

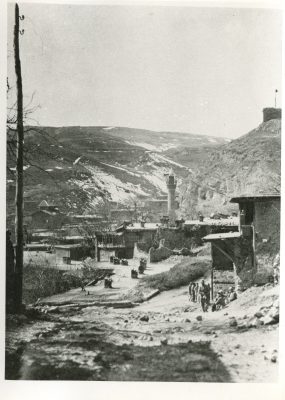

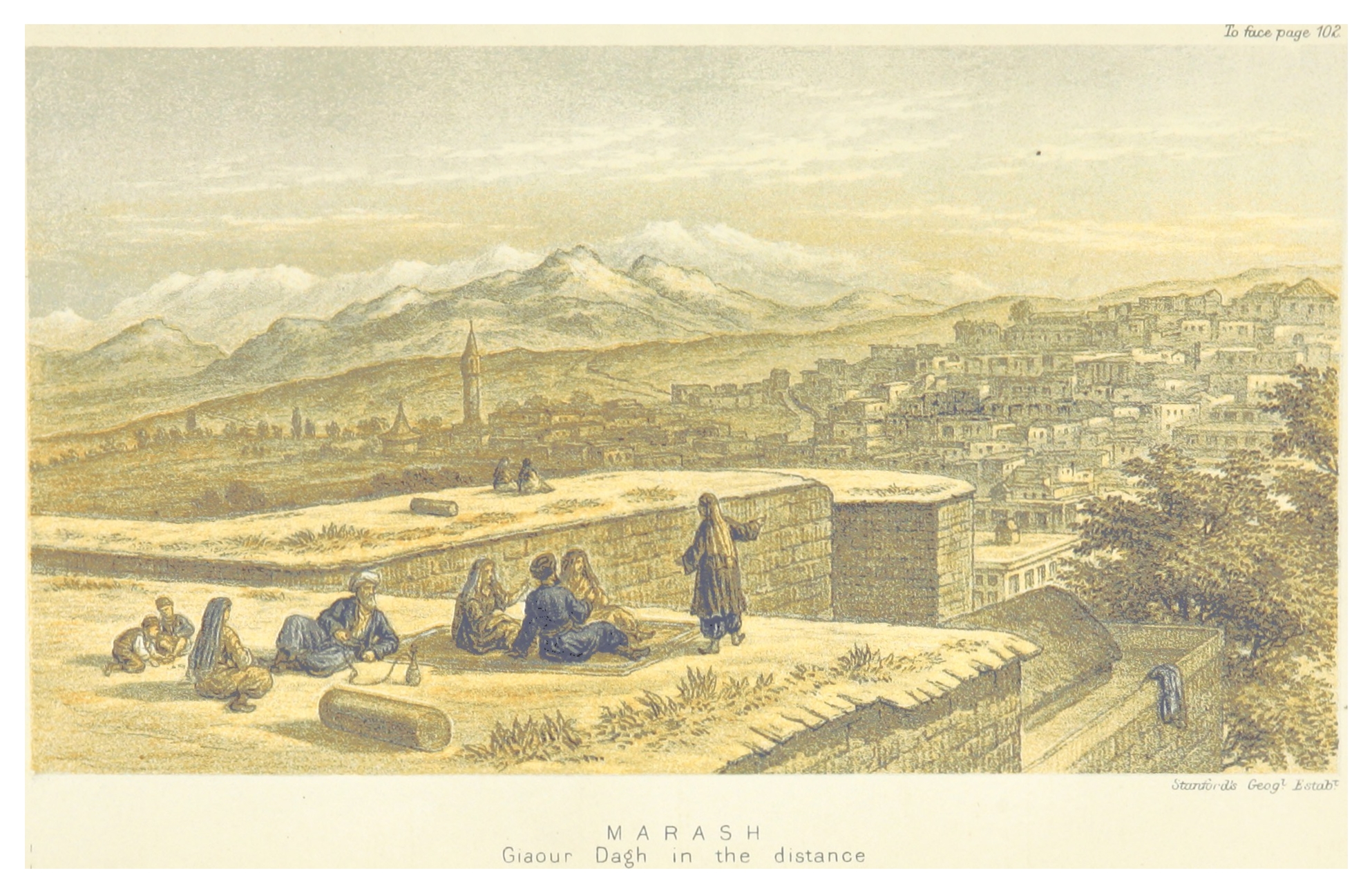

The city lies on a plain at the foot of the Ahir Dağı (Ahir Mountain).The region is best known for its distinctive ice cream, and its production of salep, a powder made from dried orchid tubers.

Population

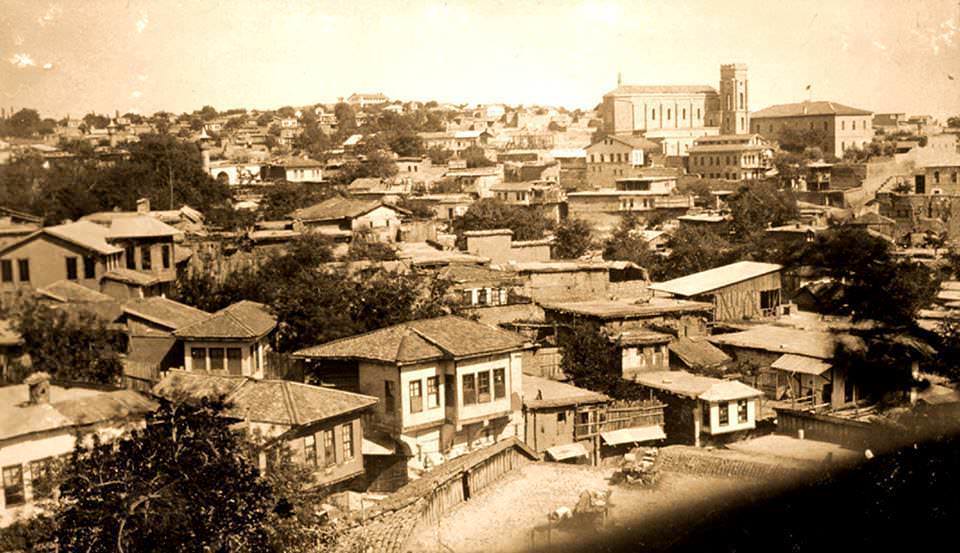

In the early days of Ottoman rule (1525–6) there were 1,557 adult males (total population 7,500); at this time all the inhabitants were Muslims,[2] but later a substantial number of non-Muslims migrated to the city, mainly in the 19th century.[3] In 1914, the 22,500 Armenian residents of the city of Maraş represented half of the overall population.[4] “Almost all of them were concentrated in a neighborhood west of the citadel that extended to an area below the monastery of Saint James, on the outskirts of the city. Within this perimeter were no fewer than five churches, several Armenian schools, an American College, and a German hospital and orphanage.”[5]

Notable Christians from Maraş

- Leo III – Byzantine Emperor (717 – June 18, 741)

Missionary Dr. George Edward White (1861-1946), president of Anatolia College in Merzifon (1913-1917, 1919-1921) - Nestorius – 5th century religious leader

- Mor Dionysius Bar Salibi (died 1171); Syriac Orthodox bishop

- George Edward White (14 October 1861, Maraş – 27 April 1946, Claremont/CA): American Congregationalist missionary and eye-witness of the genocide against the Armenians

- Ben Bagdikian (30 January 1920, Maraş – 11 March 2016, Berkeley) – Armenian-American journalist, news media critic and commentator

History

Early history

In the early Iron Age (late 11th century B.C. to ca. 711 B.C.), Maraş was the capital city of the Syro-Hittite state Gurgum (Hieroglyphic Luwian Kurkuma). It was known as ‘the Kurkumaean city’ to its Luwian inhabitants and as Marqas to the Assyrians. In 711 B.C, the land of Gurgum was annexed as an Assyrian province and renamed Marqas after its capital.

In 645, Germanicia was taken from the Byzantines by the Muslim Arabs, to whom the city was known as Marʿash (Arabic: مرعش [ˈmarʕaʃ], which is also the Syriac ܡܪܥܫ). Marash was an important Syriac Orthodox diocese; Mor Dionysius Bar Salibi (died 1171) was its bishop. Over the next three centuries, Marash belonged to the fortified Arab-Byzantine frontier zone (Thughur) and was used as a base for incursions into Byzantine-held Asia Minor by the Arabs. It was destroyed several times during the Arab-Byzantine Wars. It was rebuilt by the Umayyad caliph Muawiya I and was expanded ca. 800 by the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid. The city was also controlled by the Tulunids, Ikhshidids and Hamdanids before the Byzantines, under Nikephoros Phokas, recovered it in 962.

After the defeat of Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Philaretos Brachamios (Grk.: Φιλάρετος Βραχάμιος; Armenian: Փիլարտոս Վարաժնունի – Pilartos Varajnuni), a former Byzantine general of Armenian origin, founded a principality centred on the city, which stretched from Antioch to Edessa.

Germanikeia was captured by Baldwin I of Jerusalem in 1098, during the First Crusade, and made part of the County of Edessa, becoming an important center during Crusader rule. According to the Chronicle of Matthew of Edessa, it was destroyed by an earthquake and 10,000 people were killed, which is probably an exaggeration. In 1100, it was captured by the Danishmends, followed by the Seljuks in 1103. In 1107, Crusaders led by Tancred retook it with aid from Toros I of Armenia Minor. In 1135, the Danishmends besieged Germanikeia unsuccessfully, but captured it the next year. However, the Crusaders retook it in 1137. Baldwin of Germanikeia died in a war in 1146, while trying to recover Edessa from Nur ad-Din Zangi, which had taken the side of Joscelin II of Edessa. His successor Reynald of Germanikeia also died in the Battle of Inab against the Zengids. Sultan Mesud I of the Sultanate of Rum took the city in 1149.

Maraş was captured by the Zengids in 1151, but was recaptured by the Seljuks in 1152. Maraş was recaptured by the Zengids in 1173 and was left to Mleh. The city then passed to the Seljuks in 1174 and to the Ayyubids in 1182.

Kaykhusraw I, Sultan of Rum captured Maraş in 1208. Seljuk rule lasted to 1258, when Maraş was captured by the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, following the war with the Ilkhanate. Served by an Armenian Apostolic Church Archbishop, it became for a very short period of time, the seat of the Catholicossate of the Great House of Cilicia. Maraş was captured by Al-Ashraf Khalil, Mamluk Sultan, in 1292. It was recaptured by Hethum II, King of Cilician Armenia, in 1299. Marash was finally taken by the Mamluks in 1304.

Marash was ruled by Dulkadirs as vassals of the Mamluks from 1337–1515 before being annexed to the Ottoman Empire.

Modern period

During Ottoman rule, the city was initially the administrative center of Eyalet of Dulkadir (also called Eyalet of Zûlkâdiriyye) and then an administrative seat of a sancak in the Vilayet of Aleppo.

In December 1978, the Maraş Massacre of leftist Alevis took place in the city. A Turkish nationalist group, the Grey Wolves, incited the violence that left more than 100 dead. The incident was important in the Turkish government’s decision to declare martial law, and the eventual military coup in 1980.[6]

Destruction

1915

“On the heels of Zeytun, and still in advance of the May general deportation order, a string of nearby areas was cleared of Armenians. In mid-April the authorities called up the adult males of Maraş at large; after Armenian men registered and were taken away, their families were rounded up and marched away. The inhabitants of the villages of Furnuz and Gehen had sworn allegiance to the government and resisted demands to join the rebels. They were nonetheless deported. On April 20 Constantinople inquired as to whether their lands were fertile enough to maintain Balkan muhacirs. In May U.S. Consul Jackson summarized the Zeytun and Maraş deportations:

‘Between 4,300 and 4,500 families, about 26,000 persons, are being removed by order of the government from the districts of Zeytun and Marash to distant places where they are unknown, and in distinctly non- Christian communities. Thousands have already been sent to the northwest into the provinces of Konia, Caesarea, Castamouni, etc., while others have been taken southeasterly as far as Der-el-Zor, and reports say to the vicinity of Baghdad. The misery these people are suffering is terrible to imagine. . . . Rich and poor alike, Protestant, Gregorian, Orthodox, and Catholic, are all subject to the same order. . . . The sick drop by the wayside, women in critical condition giving birth to children that, according to reports, many mothers strangle or drown because of lack of means to care for. Fathers exiled in one direction, mothers in another, and young girls and small children in still another. According to reports from reliable sources the accompanying gendarmes are told they may do as they wish with the women and girls.’”[7]

“In Marash, whose Muslim inhabitants had a reputation for being very conservative, the German consul in Aleppo, Walter Rössler, who visited the city on 31 March 1915, observed the tension that had been reigning there since the events that had occurred in the neighboring town of Zeitun. A state of siege had been declared in the city and a court-martial had been formed. According to two American doctors, Marash’s Muslim leaders took advantage of the situation to pressure the mutesarif into imposing harsh treatment on the Armenian population. A military committee had been sent to the town around 7 April and proceeded to conduct searches in Armenian institutions and the homes of certain notables, looking for evidence indicating that a rebellion was being organized. The committee gave the population three days, from 9 to 11 April, to turn its arms over to the authorities. On 8 April, Hagop Horlakhian (Kherlakian), a notable who even had access to the imperial palace, was summoned to appear before this committee, which demanded that he see to it that the Armenian population comply with the government’s orders. There is every reason to believe that the military commission began to cooperate closely with local Young Turk leaders. Dr. C. F. Hamilton and Dr. C. F. Ranney report that on 13 April the Armenians of Marash learned that ‘a black list of 300 to 600 names’ was circulating in the city. Some Armenian notables nevertheless downplayed the significance of a document of this sort, making a game of trying to guess who was on the list.

Arrests in Marash took diverse forms. One of the methods most often employed was to invite all the men of draftable age, including those who had paid the bedel, to register for the draft. In fact, the registration campaign, which took place on 15, 16, and 17 July 1915, allowed the authorities to isolate these men, the better to liquidate them. Among the first to be arrested were 11 notables, including the auxiliary primate, Father Ghevont Nahabedian, the Protestant minister Aharon Shirajian, Garabed Nalchayan, Armenag and Nazareth Bilezigji, and Konstan and Hovnan Varzhabedian, all of whom were sent to Aleppo. In the course of a 21 April conversation with the vali of Aleppo, Celal Bey, the Protestant minister John Merril learned, moreover, that there was a plan to deport the ‘refugees’ from Zeitun, but that the government’s policy was above all, ‘to prevent such public and unordered violence.’ The American missionary’s long experience taught him how to translate this remark: ‘This is a plan for the breaking down of the Christian population without bloodshed and with the color of legality.’ He had already observed that ‘false’ reports about the Armenians had been transmitted to Istanbul ‘to be the basis for the orders now being carried out.’ Finally, he noted that the first to be deported were the best educated men, especially those who were close to American missionary circles.

In the neighboring localities, where the villagers were deported at the same time as the Armenians of Marash, the only unusual occurrence was the resistance put up at Fındıkcak.

It was quickly crushed by the army, which massacred part of the population on the spot and deported the women and children.

Some 30 men organized the squadrons of çetes, with some 20 irregulars in each, which wreaked havoc in the region. These 30 men, who also supervised the massacres and served as the members of the committee responsible for ‘abandoned property,’ were Ali Haydar Pasha, the mutesarifof Marash; Kocabaşizâde Ömer Effendi, the president of the Unionist club of Marash; Şevketzâde Şadir Effendi, parliamentary deputy from Marash; Ğarizâde Haci Effendi, a former parliamentary deputy from Marash; Dayizâde Hoca Baş, ulema; Haci Bey, the mayor of Marash; Eczaci Lutfi, a pharmacist; Sarukâtibzâde Mehmed; Eşbazâde Haci Hüseyin; Bulgarizâde Abdül Hakim; Sarukzâde Halil Ali; Şismanzâde Haci Ahmed; Şismanzâde Nuri; Ap Acuz Haci Effendi; Mazmanzâde Mustafa; Evliyazâde Evliya; Hoddayizâde Tahsin Bey; Hodayizâde Ahmed; Nazifzâde Ahmed; Hocabaşzâde Ahmed; Karaküçükzâde Mehmed; Derviş Effendi, the former mayor; Saatbeyzâde Şükrü; Eviliyazâde Ahmed, an imam; Bayazidzâde Ğadir Pasha; Bayazidzâde İbrahim Bey; Çuşadarzâde Mustafa; and Çuşadarzâde Mehmed.

The principal local leaders of the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa were Vehbizâde Hasip Effendi; Dr. Mustafa; Karaküçükzâde Mustafa; Koçabaşzâde Cemil Bey; Hoddayizâde Okbeş; Mazmanzâde Mustafa; Mazmanzâde Hasan; Haci Niazi Bey, secretary of the Department of Finance; Şakir Effendi; Cevdet Bey, the director of correspondence; Atıf Effendi, from Kilis; Ömer Effendi, an officer in the gendarmerie; Ömer’s two sons; and Fatmaluoğlu Mustafa. Those mainly responsible for perpetrating the exactions were Bayazidzâde Şükri Bey; Bayazidzâde Kasim Bey; Bayazidzâde Kerim Bey; Bayazidzâde Hasan Bey; Buharizâde Abdül Hakim Effendi; Kocabaşzâde Haci İbrahim; Ayntablıoğlu Ahmed, the assistant police chief; Çuşadarzâde Mehmed, a member of the local CUP; Safiyeninoğlu Alay Mustafa Effendi, a regimental secretary; Kusa Kurekzâde Ahmed, a belediye mufettişi (municipal inspector); Cemal Bey, a criminal court judge; and Hayrullah Effendi, a teacher in the Idadi middle school.

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 591f.

1920

After the First World War, Maraş was controlled by British troops between 22 February 1919 and 30 October 1919, then by French troops, after the Armistice of Mudros. It was taken over by the Turkish National Movement after the Battle of Marash on 13 February 1920. Afterward a massacre of Armenian civilians took place.[8] Roving Turkish bands threw kerosene-doused rags on Armenian homes and laid a constant barrage upon the American relief hospital.[9] The Armenians themselves, as in previous times of trouble, sought refuge in their churches and schools.[10] Women and children found momentary shelter in Marash’s six Armenian Apostolic and three Armenian Evangelical churches, and in the city’s sole Catholic cathedral. All the churches, and eventually the entire Armenian districts, were set alight.[11] When the 2,000 Armenians who had taken shelter in the Catholic cathedral attempted to leave, they were shot.[12] Early reports put the number of Armenians dead at no less than 16,000, although this was later revised down to 5,000–12,000.[13]

The Maraş massacre triggered a mass flight among Armenians. “In spring 1920, [U.S. consul to Aleppo, Jesse] Jackson, looking at what had just happened in Maraş, Antep, and Urfa, concluded that the Turks aimed ‘to exterminate the Armenians’. Certainly, from 1920 on, Turkish policy was at least to finally clear the Armenians out of the country. The Franco-Turkish war in southern Turkey and to a lesser extent, the parallel Greco-Turkish war to the north and west (…), acted as a major spur to, and as cover for, Armenian flight. (…)

This exodus more or less paralleled the gradual shrinkage of the French zone of control. Sometimes the Armenians joined withdrawing French columns; sometimes they preceded or followed the French. Occasionally, for a time, the French impeded evacuation. But, more often, they ordered or advised Armenians to evacuate.”[14]