Փոքր Հայք – Pok’r Hayk’: Lesser Armenia

Lesser Armenia (Armenia Minor; Armenian: Pok’r Hayk’) was the portion of historic Armenia and the Armenian Highlands lying west and northwest of the river Euphrates. It received its name to distinguish it from the much larger eastern portion of historic Armenia—Great(er) Armenia (or Armenia Maior).

During the 2nd and 3rd centuries B.C. Armenia Minor continued to exist side by side with Armenia Maior and developed at the same pace. Later Armenia Minor was conquered by Tigran II (the Great) and his Pontic Greek father-in-law, Mithridates VI Eupator who divided the region between them, so that the southern part of this area (the Harput region) would be annexed to Armenia Maior.

Lesser Armenia has been an Armenian-populated country since ancient times, until World War I, when the majority of the population west of the Euphrates was Armenian. Lesser Armenia played an important role in social, political and cultural terms in Armenian history. It had dozens of cities. Two of them are especially known, Malatya and Sebastia (Trk.: Sivas), that have played a significant role in economic, cultural and administrative terms.

Population

The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople states the pre-war Armenian population of the kaza Malatya as 17,017 people in five localities, maintaining seven churches, two monasteries and eight schools for 1,370 pupils.[1]

Armenian Settlements in the kaza Malatya

Malatya (administrative seat), Atafi (Atabey, Lower Banazi, Barghzi, Tesjede /Tejde), Old Malatya (Eskişehir, Lower town), Dzermekhti (Zirmigt), Kilayik, Kyustibek (Kyundibek), Otuzi (Hyortez)

Malatya City

Population

Until the 12th and 13th centuries Malatya was almost a homogeneous Armenian city, with a certain number of Greeks. Later, Turks gradually settled in.

According to the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1913, the city of Malatya was at that time populated by 30,000 people, with a clear Turkish majority and an Armenian population of 3,000, of whom 800 were Catholics. The U.S. consul to Harput, Leslie A. Davis, also gives a population of “about 30000” in the city of Malatya for 1917.[2] In contrast, the Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia in 1981 stated that Malatya’s population was about 40,000, half of whom (20,000) belonged to Armenian parishes. [3] Of the five churches in the city, three belonged to Armenians. Armenians were leaders in trade, silkworm breeding, silk trade and agriculture.

Raymond Kévorkian describes Malatya as the “biggest city in the vilayet of Mamuret ul-Aziz, with a total population of 35,000 to 40,000 and an Armenian population of 15,000. Although Armenians were a minority, the region, famous for its textiles, dyes, rugs, and gild jewelry, depended mainly on them for its economic development, which was reinforced by the remittances sent back to Malatia by Armenian emigrants to the Unites States. These ceased when the war broke out. Near Malatia, 1,400 Amenians still lived in Melitene – or at least what remained of the ancient city – and also in the villages of Kogh Lur (pop. 150), Orduz (pop. 400), and Chermekh (pop. 67).”[4]

As of 2021 and according to Armenian sources, there exists a tiny Armenian community of 60 people in Malatya. However, there are also several Armenians and Islamized Armenians who live in the city using Turkish names whose numbers are not clear.

Notables of Armenian, Greek, and Syriac descent

- St. Euthymios of Melitene (the Great; 377–473), Christian ascetic and saint

- Apolytikion of Euthymios the Great

Fourth Tone

Be glad, O barren one, that hast not given birth; be of good cheer, thou that hast not travailed; for a man of desires hath multiplied thy children of the Spirit, having planted them in piety and reared them in continence to the perfection of the virtues. By his prayers, O Christ our God, make our life peaceful.

- Tagavor (Stepani, i.e. „Son of Stepan“), Armenian builder of Malatya’s medresa

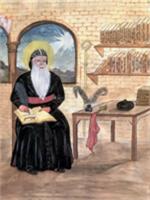

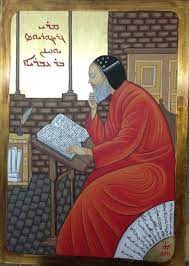

- Michael the Syrian (Syriac: ܡܺܝܟ݂ܳܐܝܶܠ ܪܰܒ݁ܳܐ, Michael the Great; Michael Syrus, or Michael the Elder, born 1126): Syrian Patriarch, author of an universal Chronicle

- Dionysios (Yaqob) Bar Salibi († 1171), Syriac-Orthodox theologician and bishop (of Amida)

- Gregorios Bar-Hebraeus (‘son of the Hebrew’; also: Bar Ebraya, Bar Ebroyo; born in the village of ʿEbra (Izoli, Trk.: Kuşsarayı) near Malatya, Sultanate of Rûm (1226–1286), a universal scholar and Maphrian of the East of the Syrian Orthodox Church.

- Malatyalı (Ermeni) Süleyman Pasha (1607–1687), Ottoman Grand Vizier (1655-1666) of Armenian descent

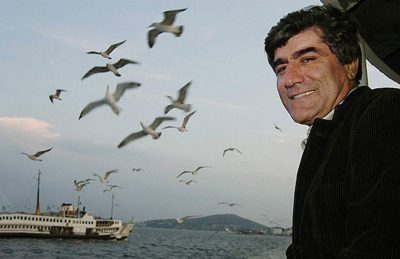

- Hrant Dink (1954–2007), Armenian journalist, editor of the newspaper Agos and victim of an right-wing extremist murder

Yetvart Danzikyan, editor-in-chief of the Agos weekly newspaper, thinks it would be better if the Armenian Patriarchate in Istanbul had done the renovation but said it was financially impossible. (source: https://turkishminute.com/2021/09/02/nian-church-in-malatya-hosts-first-religious-service-since-1915-as-a-culture-center/)

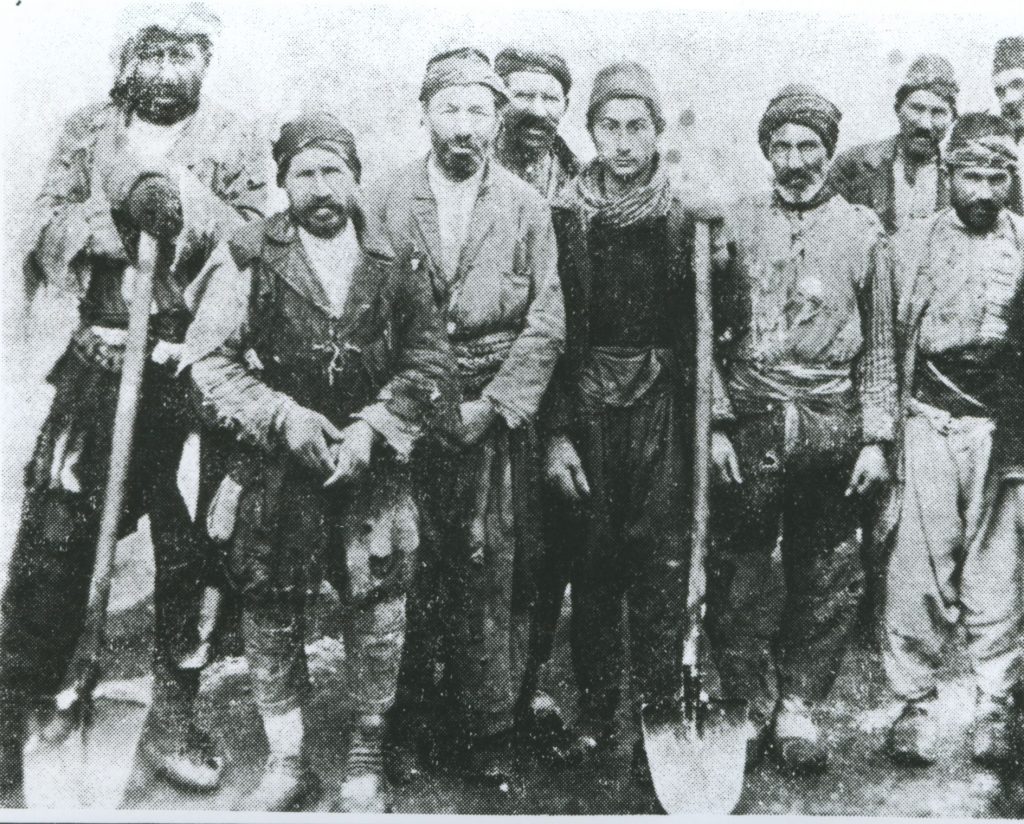

Destruction

During the Hamidian massacres of 1895-1896, 7,500 Armenian civilians were killed by fanatical Muslims and Kurdish irregular units in Malatya alone. Subsequently, a Red Cross rescue team sent to Malatya and led by Julian B. Hubbell, found that 1,500 Armenian homes had been looted and 375 completely burned.

In the spring of 1915, the town’s Armenians were arrested by Ottoman authorities and deported to the Syrian Desert. The survivors of the Ottoman genocide settled in various countries. Armenians who fled to Armenia founded the Malatia-Sebastia neighborhood in Yerevan.

“One of the worst places…”: Malatya 1915 To 1918 As Witnessed By German Missionaries

Introduction

On 5 March 1989, Marlene Petersen sent a copy of her father’s diary to Tessa Hofmann. From the summer of 1914 until 11 August 1915, Hans Bauernfeind († 1941) had been the deputy director of the mission of his brother-in-law, the German missionary Ernst Jacob Christoffel (4 Sept 1876 – 23 April 1955; today Christoffel-Blindenmission im Orient – Christoffel Mission for the Blind in the Orient). After his return from Turkey, Bauernfeind worked as a pastor in a tiny village in Thuringia. The diary he kept from 22 March to 30 August 1915 comprises 130 typewritten pages.

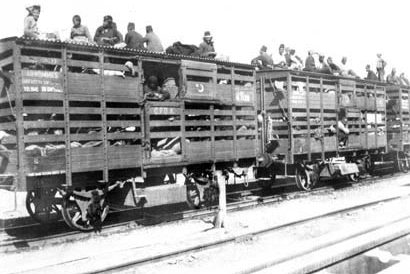

Bauernfeind’s chronicle concerns the individual stages of the Armenian extermination in the city of Malatya as well as on his return journey to Constantinople: weapons seizures, the arrest, torture and extermination of over two thousand Armenians of Malatya, the passage of at least 20000 deportees from the city and province of Sivas as well as 5600 from Mezre, labor battalions.

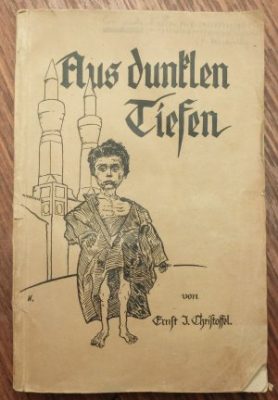

The diary is complemented by the book publications of the mission founder and leader Ernst Christoffel, who became an eyewitness to the effects or the final stage of the genocide from 1916 to 1918. Of his five publications describing events in the Ottoman Empire and in Malatya[5], two are of particular importance for the history of this city and Christoffel’s missionary institution Bethesda: Aus dunklen Tiefen (From Dark Depths; Berlin 1921) contains Christoffel’s most comprehensive account of his relief work from April 1916 to February 1919 and was written under the impression of those years. “Zwischen Saat und Ernte” (Between seed and harvest; Berlin 1933) offers an overview of mission history and, from a greater temporal distance, adds further details to the Bethesda stage. Thus, on the basis of these texts, it is possible to gain an almost complete overview of the history of the Mission for the Blind and its Bethesda station in Malatya, which until now was considered the most unknown of the German mission stations in the Ottoman Empire.

The significance of Bauernfeind’s and Christoffel’s testimonies stems from the importance of Malatya in the course of the genocide program: located on the major caravan route leading from Samsun on the Black Sea coast to Baghdad, Malatya became an important transit station and gathering point for Armenian deportees from the northern and northeastern Vilayets. “Malatya,” Christoffel wrote in retrospect, “was one of the worst places. (…) The fanaticism of the cliqué that held sway in our city was greater and more bloodthirsty than in other places. Even when bread distribution and soup kitchens were later set up in other towns by missionaries, I should not have dared to do so outside the institution” (Tiefen, p. 29)

The History of the Christian Mission for the Blind in the Orient

The Beginnings: 1906 to 1909

Ernst Christoffel, a craftsman’s son from Rheydt in the Rhineland, and his sister Hedwig (d. 1959) first arrived in the Ottoman Empire in 1904, where they ran an orphanage for victims of the massacres of 1894-96 in Sivas on behalf of Swiss friends of the Armenians until the winter of 1906. At that time, Christoffel maintained good contacts with the representatives of the German Aid Society for Christian Charity in the Orient (Hilfsbund für Christliches Liebeswerk im Orient), so that after the expiration of his contract in Sivas, the Hilfsbund initially wanted to give him a teaching position at the newly founded teachers’ seminary of the Aid Society in Mezre. The Hilfsbund board did not keep its contractual obligations, and the post intended for Christoffel was filled by the Methodist Sommer, allegedly because Christoffel was suspected of free-church tendencies and he had not gotten along with the authoritarian board member Ernst Lohmann.[6] Christoffel, who wanted to continue his work in Turkey despite these difficulties, had only the option of becoming a “free missionary.” An experience with a blind man in 1906 moved him and his sister to put their future work entirely at the service of these handicapped people: “They saw how Islam, devoid of love, has no organ to understand the plight of these people. They saw how a petrified oriental Christianity passed by indifferently the blind brother, the blind sister.”[7] His disappointing experiences with the Hilfsbund obviously made Christoffel look for his own niche in the mission business and explain his efforts to work in places where there was no competition from American or other German missions (Hilfsbund, Orientmission).

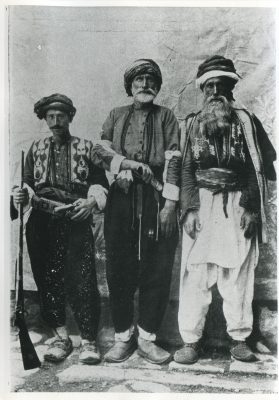

Small groups of friends in Holland, Switzerland and Germany – mostly single, elderly and educated women – provided the funds to feed ten blind people for a year. On 8 January 1909, Ernst and Hedwig Christoffel arrived in Malatya, ancient Melitene on the upper reaches of the Euphrates River. At that time, the long garden city, situated in a fertile plain, had about 60000 inhabitants, one third of them Armenians.[8] The surrounding area was and is predominantly populated by Kurds, which is why the founder of the mission always referred to this part of historic Lesser Armenia as Kurdistan.

The year 1909: The foundation of the mission station in Malatya

When the siblings arrived, there was a famine. It affected mainly the Armenians, who had not yet recovered from the massacres of 13 years before. Three-quarters of Malatya’s Armenian homes lay in ruins (Saat, p. 138). Contrary to their original mission, the mission for the blind, the Christoffels immediately set about relief work among the suffering Armenians, helping them through the difficult winter.

At that time, two missionary works already existed in Malatya: French Capuchin monks maintained a branch with a school. They left their station in 1914 at the outbreak of war.[9] The Dane Jensine Ørtz (Jensine Oerts Peters [‘Majrik’ – little mother]; b. 1880, d. in the 1960s) had been w[orking as a sister in Malatya since 1906, where there existed at that time already a small Armenian Protestant congregation under pastor Patveli Trdat Tamrazian. The authorities had forbidden Mrs. Ørtz Peters to proselytize (she nevertheless secretly distributed Bibles, among others to the mayor Mustafa Ağa), but she was allowed to open a kindergarten, which she ran with two teachers and an Armenian catechist, Sara Baci (“Sister”).

At the end of April 1909, when the population of Malatya was expecting Armenian massacres, Ernst Christoffel and Jensine Ørtz Peters made a considerable contribution to easing tensions by regularly appearing together in public (Saat, p. 65 f.). At the time, the Danish woman and the two German siblings were third and fourth, respectively, on a death list of those whom the organizers of the massacre in Malatya intended to liquidate with the help of Kurdish gangs. A telegraphic call for help from Christoffel to the German embassy in Constantinople, which he asked for ‘Reich protection’, remained fruitless. It was not until half a year later that the consulate in Aleppo inquired whether German imperial interests were endangered in Christoffel’s mission (ibid.). Christoffel later mentioned this incident on several occasions as a vivid example of German bureaucracy and lack of commitment to German missionaries. However, the courageous intervention of a Turkish infantry captain saved Malatya from another massacre in 1909 (Saat, p. 70).

Jensine Ørtz Peters left Turkey in 1914 due to shattered nerves, but resumed her Armenian work in Tekirdağ (Rodosto) in eastern Thrace on 12 March 1922. She opened a lace-making school there, which provided a livelihood for young Armenian women freed from Muslim households. After the Armistice of Mudanya, she, along with 4000 Armenians, had to leave Tekirdağ. Against the initial resistance of the municipal authorities, she helped the exiles to land in Thessaloniki and, not least because of this act, went down in the history of the Armenian people as a savior of deportees and survivors of the genocide.

Bethesda

In 1921 Christoffel wrote retrospectively: “It was the only institution of its kind in European and Asian Turkey, apart from the home for the blind connected with the Syrian orphanage in Jerusalem. (…) The home was to be a refuge for all those for whom the program of the other missionary societies did not offer room, without distinction of race or creed. First and foremost, the blind were considered. However, since no person seeking help could be turned away from Bethesda’s gates, we also came to cripples, the insane, and to a number of normal orphans, who, however, were nobody’s children in the fullest sense of the word (…). The Bethesda family presented a colorful picture. All ages were represented, from the infant to the world-weary old man; blind, crippled and stupid, healthy and sick, Armenians, Turks, Kurds and Syriacs called Bethesda their home” (Tiefen, p. 6).

In contrast to the Hilfsbund and the Orientmission (later: Dr. Lepsius-Orientmission), at least programmatically, Armenian aid was not the focus of the work of the Blind Mission.

A Turkish widow had sold the house to the missionary brothers and sisters, and the large plot of land was made available by Pastor Trdat Tamrazian. It enabled the ‘Bethesda family’ to do their own farming. “Our institution was located a good ten minutes from the outskirts of the city, completely alone. (…) But the traffic between the city and us was generally a very brisk one” (Saat, p. 152).

Two problems hampered the work of the small station from the beginning: chronic lack of money as well as isolation. The next German mission was located a day’s journey to the northeast, in Mezre. It was a station run by Pastor Ehmann for the German Hilfsbund für Christliches Liebeswerk im Orient (Aid Society for Christian Charity in the Orient), the largest German mission in the Ottoman Empire until the end of the war (Saat, p. 178). The provincial capital, Sivas, with its Swiss orphanage for girls, also considered a German institution, was four days’ journey to the northwest.

During the World War, the lack of a German field post station in Malatya had a particularly disastrous effect. The mission’s telegraphic or epistolary communications with the embassy in Constantinople or mission friends back home now depended entirely on Ottoman postal officials being willing to carry mail or on German military personnel who happened to be passing through carrying mail to Germany or Constantinople (Tiefen, p. 70).

Nevertheless, the Christoffel Mission for the Blind in Malatya made such progress that as early as 1913 there was thought of establishing a branch. “In addition, there was a second reason: from the beginning our work was aimed at Mohammedans” (Saat, p. 96). Christoffel set his sights on the provincial capital of Diyarbekir, which apparently presented an even greater challenge to the missionary than Malatya precisely because of the difficulties present there: “The Mohammedan population there was considered particularly fanatical, and the Armenian-Gregorian population particularly intolerant of the mission’s efforts. There was a small Armenian Protestant community dependent on the American Board. But in spite of various attempts on the part of the Germans and the Americans, no actual missionary state was founded. As far as I could find out, the biggest obstacle was the Armenian bishop. In 1898, Dr. J[ohannes] Lepsius had collected 100 massacre orphans here. The house was closed by the Turkish government at the end of the same year. In April 1900, Pastor von Bergmann had come to Diarbekir on behalf of Dr. Lepsius, possibly to establish a base for the Lepsius Mission here. Bergmann died of typhoid fever in the same year. (…) The absence of any other missionary society also strongly determined our decisions. (…) The then Vali of Diarbekir, a finely educated Turk, was fully sympathetic to our intentions” (Saat, p. 97).

A first reconnaissance trip in 1913 was followed by a second one in July 1914, which was less encouraging: Diyarbekir was now governed by the notorious Reşid Bey, who “proceeded with sadistic cruelty in the Armenian atrocities of the following year (…)” (Saat, p. 98). Despite a humiliating confrontation with Reşid, Christoffel optimistically stuck to his Diyarbekir plans: “The Valis came and went” (Saat, p. 99). Via Aleppo, where Christoffel attended the German girls’ school run by the Kaiserswerth Sisters, the journey continued by train to Beirut, from where Christoffel planned to disembark for Trieste and on to Germany. There he hoped to find financial and organizational support for the Diyarbekir branch. But already in Aleppo, news of the outbreak of the world war reached him. Christoffel nevertheless continued his journey home to serve in the German army: First in the medical service, then as a hospital chaplain in Ahrweiler.

Since Ernst Christoffel’s departure on 3 July 1914, Bethesda remained under the deputy leadership of Hans Bauernfeind, who had married Hedwig Christoffel in 1913. Besides them, another German mission worker lived in Bethesda, the blind teacher Betty (also: Betti) Warth. The ‘institutional family’ (Anstaltsfamilie) at that time consisted of 85 persons, most of them apparently of Armenian ethnicity. In August 1914, due to Bethesda’s inflationary financial crisis, Bauernfeind sent home 60 ‘housemates’ who had relatives – a measure for which, according to his diary, he was apparently reprimanded by Christoffel: “At the time, I was reproached for this radicalism” (p. 100).

The Year 1915

Looking back on the extermination of the Armenians, Christoffel wrote in 1933: “How should the German missionary behave? The Armenians to a large extent are objects of our missionary activity. The Turks our political allies. Injustice on both sides. The Armenian people was the weaker, the one exposed to annihilation, and in addition not revolutionary in its mass. Whoever helped them was in opposition to the government’s policy. Fully aware of this opposition, I took care of the persecuted Armenians until the end of the war. I would have done the same with the Turks if they had been the persecuted ones” (Saat, p. 278).

As fate would have it, ‘Hayrik’ (Father), as the Armenians called Christoffel, was absent in 1915. At that time, in the midst of the crisis, his deputy frequently confused victim and perpetrator. In the dilemma between political loyalty to the alliance and Christian or even general humanity, he often opted for the first principle. Anti-Armenian prejudices clouded his judgment, German obedience to authority and lack of civil courage paralyzed his ability to act. As the reflections in his diary show, he was the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time. Coming from an old pastor’s family, Bauernfeind had belonged to the circle of supporters of the Mission for the Blind before he married Hedwig Christoffel. He lacked the training and, for long stretches, the clarity of vision and experience to lead an isolated Oriental mission, especially under wartime conditions and difficult political circumstances. Bauernfeind wrote and spoke French, as well as some Turkish and apparently better Armenian. When communicating with Turkish officials, he usually used Armenian interpreters.

His submissive spirit and prejudice against Armenians worked into the hands of the local enforcers of the C.U.P.’s extermination plans several times and psychologically limited his willingness to rescue. For example, he refused to admit children who had managed to escape from deportation convoys to Bethesda and even sent former members of the ‘Bethesda family’ back on the deportation route. Anyway, only a few deportees or Armenian residents of Malatya managed to penetrate the mission, which was guarded by a gendarme (‘zaptiye’). The Bauernfeind couple was quite happy about this isolation, as it shielded them from the petitioners, whom they believed they could not help anyway, either materially or by intervening with the authorities.

Bauernfeind did, however, intercede with the authorities on behalf of arrested Protestant Armenians from Malatya, albeit ultimately unsuccessfully. On 9 June 1915, he protested, also ineffectively, against the torture and murder of Armenian prisoners in a letter written in French to the kaymakam of Arha (also Arrha or Arga; Akcadağ), Vasfi Bey, who at the time held the office of mutesarrıf by proxy. Ten days later, he received the first evidence that Armenians who had been killed were buried nightly on the mission grounds. These experiences and the increasingly obvious fact that the Armenian prison inmates as well as members of the workers’ battalions ‘disappeared’ determined Bauernfeind’s diary entries in the first half of July 1915, in which he clearly speaks several times of a “masterfully organized, long since prepared mass judicial murder” (Diary, p. 61), for which the Ottoman government was responsible. However, the influence of Ottoman officials, especially the Mutesarrıf, soon pushed this temporary clear-sightedness back into the background. He also took the report of an American missionary employee, Mary L. Graffam, who had voluntarily accompanied the deportees from Sivas, as a welcome relief for the government: On this section of the deportation route – Miss Graffam was not allowed to accompany the deportees until Urfa – there had been no dramatic incidents, at least in her convoy.

Bauernfeind and his wife longed to leave Malatya and their responsibilities early on. On 7 July he noted: “For apart from the financial plight, which hardly permits another winter here, we are here firstly always endangered as eyewitnesses, secondly inwardly impossible. And finally: after we have experienced this, our task here is done; now our duty lies in Germany – to be witnesses of the truth” (Diary, p. 54). Fear of the “Russian danger” formed another motive.

The main obstacle to a quick departure, however, was the remaining ‘Bethesda family’. After the first massacres in Malatya, Bauernfeind made a plan in early July 1915 to evacuate his charges to Mezre to the ward of Pastor Ehmann. When he learned of the imminent deportation of Malatya’s Armenians to Urfa, he had offered the Mutesarrıf of Malatya to himself transfer the Bethesda Armenians to Urfa. It only gradually dawned on Bauernfeind that Urfa would not be the last station of the deportation.

But the Ottoman authorities did not tolerate any European travelers on the southern sections of the deportation routes at that time, and the Hilfsbund missions in Mezre and Maraş refused by telegraph to accept the Bethesda remnant family: they were in trouble themselves and had to fear being closed down. At the end of July, the leadership of the Christian Mission for the Blind in Germany apparently repeated its demand that the ‘Bethesda Family’ be dissolved. Resignedly, Bauernfeind noted on 29 July: “If it should not be possible for us to travel via Mezre, Urfa, or for us to accommodate our house in Mezre, we should go to Constantinople as quickly as possible in order to take the necessary steps with the embassy there. That seems to be the most important task for us now. After all, one does not know there how it looks like here inside. But what is to become of our blind and gouty people? It is easy to say, as Dr. Schroeter wrote to us today, that we should send them all away. To strike them all dead would be much more merciful. If we cannot place them safely in Mezre or elsewhere, we must not leave at all. And yet we must, for money is not to come again, and indeed we can hardly stand it here: in the midst of all this horror we have to keep silent and watch idly, while outside one knows nothing of everything” (p. 96).

On 31 July 1915, Bauernfeind received Christoffel’s renewed telegraphic order: “Release all housemates immediately!” (Diary p. 100). Bethesda still had 22 blind and orphans at this time (Diary p. 98). Those sent by Bauernfeind to their relatives in 1914 met the general fate of Armenian deportees. Only six of the sixty inhabitants released in 1914 survived the genocide, as Christoffel noted in 1916: “They were slain, starved, lost. Of the six (survivors), 3 found their way to Bethesda. As for the rest, I have received news of only a few of them. The crippled Mariam Baci died of starvation, the little blind Levon also. (…) The blind Khattun is said to have been drowned in the Gölcük [today: Hazar Gölü]. The Gölcük is a mountain lake near Mezereh where thousands of Armenians were drowned” (Tiefen, p. 16).

On 31 July, coinciding with Christoffel’s dissolution order, the Mutesarrıf held out the prospect of rescuing all Armenian employees to Bauernfeind on the condition that the Bauernfeind couple remain in Malatya (Diary p. 98). When Bauernfeinds refused, the Mutesarrıf insisted on the deportation of all male Armenians living in Bethesda, including the blind. To satisfy him, Bauernfeind was willing to sacrifice to him “the only sighted, slightly taller boy” (Diary p. 105).

Although Bauernfeind possessed sufficient evidence of the perfidy of Ottoman officials, he left Malatya on 11 August 1915, together with his wife as well as Miss Warth, Miss Graffam and their Armenian protégés from Sivas, the old preacher’s wife ‘Pampish’[10] and the 17-year-old teacher Levon: “And it now seems to us the most natural and safest thing to do: To trust the Mutesarrıf and the government here. We have no fear that anything will happen here in time. It is also decidedly best for house and property” ( Diary, p. 103). He had agreed with the Mutesarrıf that Bethesda should be under the direction of Makruhi, the widow of the missionary Karapet, who had been killed in the meantime, and Khoren, a teacher for the blind who was almost blind himself, until the return of ‘the director’ Christoffel.

The small group traveled in two wagons and was probably not coincidentally accompanied by Ottoman officers who also wanted to go to Constantinople. In their luggage, Bauernfeinds had a letter of legitimation from the Mutesarrıf, which assured them safe conduct to Constantinople and the accompaniment of two gendarmes. They had been talked out of their planned route via Maraş : ” (...) the journey to Maraş was now too dangerous. And since there are no reliable Zaptiyes [gendarmes], we finally decided to abandon this travel plan (…). Now, God willing, we want to leave by wagon (…) via Sivas, Caesarea [Kayseri] to the Baghdad Railway.” ( Diary, 6 August 1915)

Personae dramatis – Acting Persons in Malatya of the Years 1915 to 1919

Armenian protagonists

Khoren

Himself almost blind, Khoren worked as a teacher for the blind in Bethesda. He often served as an interpreter for Bauernfeind in his conversations with Turkish officials. After Bauernfeind’s departure in August 1915 until Christoffel’s arrival in April 1916, Khoren and Makruhi ran the mission house together.

Khosrov Efendi Kesheshian

Khosrov Efendi, pharmacist at the site, was among the confidants of the Bethesda missionaries. He belonged to the party leadership of Dashnaktsutiun in Malatya and on 26 May 1915, he was one of the first Armenians of that city to be arrested, allegedly for hiding a rifle. After discharging a specially purchased weapon, he was released. On 29 May, Khosrov Efendi was summoned again. Bauernfeind stood up for the “friend of the house” Khosrov Efendi when he was arrested again, but was soon convinced by the Muhasebeci (Council of Accounts) that Khosrov was a dangerous revolutionary: “Not one to be trusted …” (Diary, 3 June 1915 ).

Under torture, Khosrov Efendi named “ (…) a place in Babukht (…) where weapons are said to be hidden. They took him there yesterday and dug for 4 hours in vain. Moreover, Khosrov Efendi is said to have taken poison (…)” (Diary, 8 June 1915 ). His suicide attempt failed. Hans Bauernfeind, in his letter to the Mutesarrıf of Malatya of 9 June 1915, also interceded for Khosrov Efendi – in vain. He was murdered in June 1915.

Gabriel Efendi

was a lawyer in Malatya and advised the German missionaries in legal disputes. In May 1915 he was thrown into prison. Hans Bauernfeind wrote in his diary on 29 May 1915: “On the way back I met Gabriel Eff(endi), who had also just come out of prison, from where he had been released on condition that he hand in a rifle by today. He now wanted to see about being able to buy or borrow one somewhere, otherwise he felt he would have to die.” Entry of 31 May: “Gabriel Effendi has handed over a rifle belonging to his deceased brother-in-law, since he claims not to have one himself – which we believe him to have – is thereupon released for the time being; but his own is demanded. He has also been beaten, though in the lightest way, with a few weak blows to the head; this seems particularly crude because, as a lawyer, he has devoted his whole life to the government and is regarded by the Armenians as half a Turk.”

On 13 June 1915, Gabriel Efendi was thrown back into prison. He was not to leave it alive.

Garabed (Karapet) Chaderdjian

was the cook and buyer of the Mission for the Blind in Bethesda since about 1910 and lived in the Mission building with his wife Makruhi and his children Willi (Chad, proper Chaderdjian, died in the USA in 1989 ) and Viktoria. Garabed had “(…) by his faithfulness and his agility (…) a great merit in the development of Bethesda” (Tiefen, p. 16 ).

On 6 April 1915 he was arrested and disarmed (he exercised gendarme function), but was released for the time being. In June 1915, Garabed, like the other Armenian men of Malatya, was killed. Bauernfeind’s clumsiness and faith in authority possibly prevented his rescue (Diary, 19 April 1915).

Heinz, Otto and Liesel

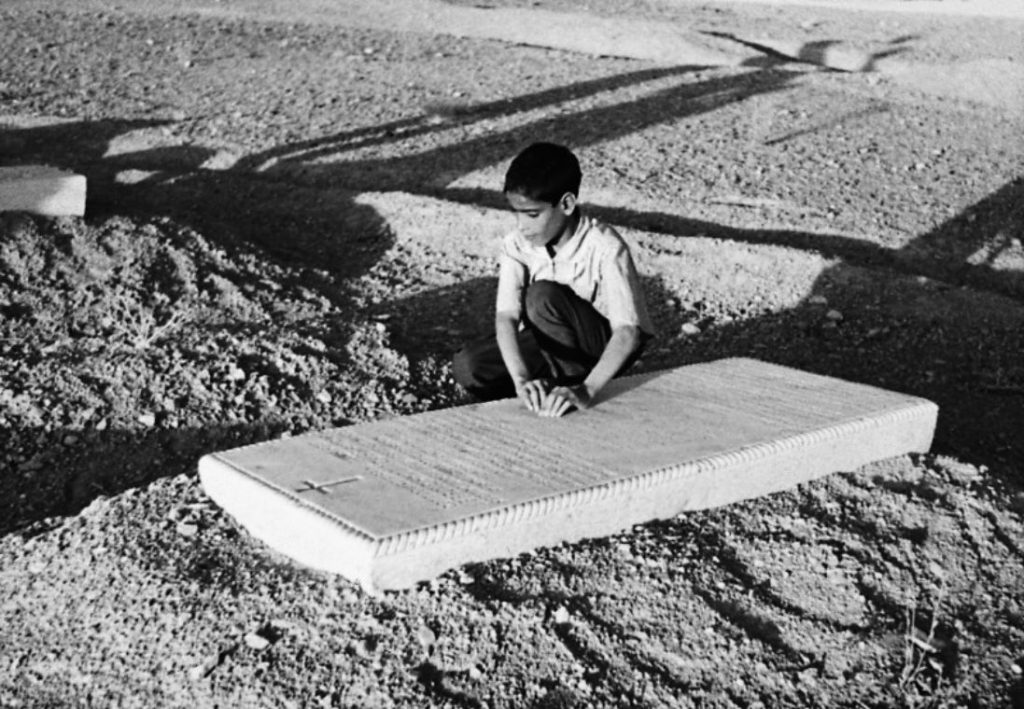

are the three “adopted children” of Ernst Christoffel, whom he had taken in at Bethesda after his return in 1916. Heinz, about 9 years old in 1919, was a brother of the murdered Bethesda employee Krikor (Grigor). “From a numerous family he and a sister, who found themselves after our departure, were left. When I returned to Malatya in the spring of 1916, I heard that he was tending sheep for a Kurdish farmer. I had taken him out of this slave relationship” (Tiefen, p. 77f. ).

Otto, an Armenian seven years old at the time, had been brought to Bethesda in 1916 by a Turkish woman who had picked him up on the street and taken care of him. “He had completely forgotten his Armenian language and believed himself to be a Turk” (Tiefen, p. 78).

When Christoffel wanted to bring his “adopted children” to Germany in 1919, Otto’s stepbrother, Baron (Paron – “Mister”) David, took Otto to live with him. Heinz was also taken from Christoffel at the instigation of the British Embassy and the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, which Christoffel felt was unjust. As Bauernfeind’s daughter informed in a letter dated 1 January 1990, Otto did later reach Germany and was adopted by Christoffel’s sister Maria, which was denied to Christoffel because of the German adoption laws. Under the name Otto Christoffel, the young Armenian became a teacher for the deaf and dumb and lived as a pensioner in Neuwied in 1990.

Liesel, a Kurdish girl about six years old in 1919, had already come to Bethesda as an infant. Christoffel was able to bring her to Germany in 1919 as the only one of his “adopted children”.

Krikor (Grigor)

Ernst Christoffel described him as follows: “Krikor was actually the stable boy, but had gradually become the boy for everything through his attitude. Stable, garden, yard, vineyard, that was all his domain. In addition, he still found time to keep my private room in order and to look after me. He had hot, boiling blood, and he did not know how to be irascible; besides, he was easy to guide like a child, was as faithful as gold and had a deep, infinitely sensitive mind” (Tiefen, p. 16f. ).

In 1915 Krikor might have been about 18 years old. On 27 May 1915 he was “soldiered” (Diary, 27 May 1915), on 4 June he was arrested and locked up in the barracks. On 7 June, Bauernfeind managed to get him out again. But on 30 June, Krikor met the general fate of his compatriots in Malatya – he was imprisoned in a han (karavanserai, inn) together with other Armenian soldiers, including his seventeen-year-old brother, and murdered shortly afterwards.

Dr. Mikael Efendi Chanian

The businessman Dr. Mikael Chanian, brother of Khosrov Efendi, married to wife Veronika, belonged to the Protestant community of Malatya. On 7 June 1915, Dr. Mikael and his son Mihran were arrested and “(…) put into the prison where 150 people are crammed into a very small, low room without windows and any ventilation (…) “ (Diary, 8 June 1915).

Hans Bauernfeind interceded, unsuccessfully, on behalf of Dr. Mikael and his son. Both were murdered in June 1915. Mrs. Veronika tried to escape to Mezre on 13 June 1915. On the way there she was completely robbed. Hans Bauernfeind saw her again – she was among the deportees from Mezre who passed through Malatya on 13 July 1915.

Badveli (Patveli) Trdat Tamrazian (Tamzarian)

the Protestant pastor in Malatya, had given Bethesda the adjacent properties. In June 1915, ‘Badveli’ (pastor) Tamrazsian repeatedly and insistently urged Bauernfeind and his wife to preach and assist the prisoners with him in prison: “We very much recognize his intention, but consider both as impossible as they are futile, just now.” (Diary, p. 32 ). Badveli Tamrasian was arrested in June 1915 and probably fell victim to the massacres. However, the 1918 report of the American consul Davis mentions a “Badveli Dertad Tamzarian” who helped him care for survivors in Harput in 1916.[11]

Turkish (Muslim) protagonists

Habeş / Habesh (“Ethiopian”)

He was a blind Turk and one of the oldest Bethesda infants. He provided invaluable service to the mission during the most difficult times: During the mass arrests of Armenians in May and June 1915, when they dared not send the station’s Armenian employees to the market, Habeş did all the shopping despite his blindness. At the time of the great famine in Malatya, in 1916 and 1917, Christoffel succeeded in getting his protégés through, not least thanks to Habeş: “The connections of our blind Habesh often served us well. He knew how to find and buy from his acquaintances a bushel of barley here and a sack of corn or a cartload of pumpkins there” ( Tiefen, p. 32 ).

When Christoffel had to leave Bethesda in February 1919, Habeş was already deathly ill in bed and died of consumption a few weeks later. Christoffel wrote in 1921: “We will keep him in grateful memory as one who remained faithful to Bethesda in the most difficult times and served despite the scorn and hostility of many of his fellow Mohammedans” ( Tiefen, p. 15 ).

Hashim / Haşim Beg

Turkish landowner, neighbor of Bethesda, and influential man in Malatya, was, according to Mustafa Ağa, among the masterminds of the arrests and massacres. Haşim Beg took direct advantage of this: He and his sons enriched themselves with the properties of the killed Armenians (Diary, 8 July 1915 ). In retrospect, Christoffel stated, “It was one of the first families in the city (…). The father [Haşim Beg], who was a deputy, and two of his sons were among the leaders of the clique that had orchestrated the extermination of Christians in Malatya” (Tiefen, p. 62 ).

Müfettiş (Inspector, overseer)

Although mentioned only twice in Bauernfeind’s diary, this inspector, sent from Constantinople, seems to have been central to the course of the genocidal program in Malatya, a connection that Bauernfeind, however, failed to grasp. The Müfettiş, whom Raymond Kévorkian identified as Boşnak (Bosnian) Resneli Nazim Bey[12], arrived at the time of the inter-regnum between the terms of the two Mutesarrıfs, apparently as a deportation inspector. The period of his stay in Malatya saw the mass house searches, arrests, torture, and murder of the city’s Armenian men. Because of his apparently outstanding position, the Müfettiş was passed away with great pomp in Malatya on 6 June 1915, with the simultaneous release of prisoners who took over the bloody massacre work shortly thereafter.

Muhasebeci (Accountant, bookkeeper)

Accountant in Malatya, is mentioned several times in Bauernfeind’s diary. Bauernfeind was on quite familiar terms with him. Muhasebeci was one of those who successfully conveyed the official Turkish propaganda on the Armenian question to Bauernfeind time and again.

Mustafa Ağa Aziz Oğlu (Belediye Reisi)

The Belediye reisi (city leader, mayor) of Malatya was of outstanding importance for the fate of Bethesda and its inhabitants. Ernst Christoffel wrote about him: “He was the mayor of Malatya and came from a noble family that had immigrated from Baghdad some time ago. (…) Mustafa Ağa was an old friend of Bethesda. Since the beginning of the work, he had sponsored it. He had stood up for us and our work in many difficult situations, especially at the time of the Adana massacres in 1909. Christians and missionaries were also to be massacred in Malatya at that time. At that time Mustafa Ağa said to me, ‘As long as I live, nothing will happen to you.’ However, as it became known later, on the list of those to be murdered before the general massacre, his name was even before ours. – The relatively quiet development of Bethesda until the outbreak of the World War would have been inconceivable without his active benevolence, and we have always considered it a kindness of God that our work had such friends” (Tiefen, p. 64).

Shortly after the arrival of the Christoffel brothers and sisters in Malatya in 1909, Mustafa Ağa’s humanistic attitude was revealed to them: His name was on the blacklist of personalities to be murdered because he belonged to the “(…) influential Turks” who “were known to be committed to the peace of the nations” (Saat, p. 66 ). It was through Mustafa Ağa that the newcomers first learned of the “Cilician bloodbaths”: “He (Mustapha Agha, ed.) told me (…) that Christian massacres had taken place in Cilicia, Adana and Tarsus, to which many thousands of Christians had fallen victim. Since our friend as a true Oriental tended to exaggeration, I did not give full credence to his messages. Nevertheless, the said corresponded to the facts, yes it remained still far behind the bloody reality” (Saat, p. 65 ).

Hans Bauernfeind experienced many situations with Mustafa Ağa that resembled the one described above from 1909. Again, the mayor was the first and only one who tried to make the Germans understand the scope of the events right at the beginning of the Armenian persecutions and to inform them about what was happening in the city. Again, he encountered doubts in their minds about his credibility. But Bauernfeind, unlike Christoffel, was not able or willing to understand how much Mustafa Ağa’s alleged Cassandra calls corresponded to the “bloody reality” until his departure in August 1915. Moreover, the clearer the signs of a general extermination and deportation of Malatya’s Armenians became, the more obviously Mustafa Ağa’s information was supported by reality, the more decisively Hans Bauernfeind labeled the mayor as insane.

In his diary, Bauernfeind often criticized Mustafa Ağa’s pro-Armenian stance and did not consider him a reliable source of information. He was “(…) completely under the Armenian influence and on their side” (Diary, 9 June 1915 ), indeed he was “(…) hated and endangered because of his Christian friendliness as ‘Gavur‘” (Diary, 7 July 1915). The upright mayor, who clearly saw the catastrophe awaiting the Armenian people, did not understand the passive attitude of the German missionaries. For statements such as “The Armenians are all waiting for you to redeem them” (Diary, 9 June 1915), he earned only incomprehension from Bauernfeind.

Mustafa Ağa did not limit himself to commenting on what was happening; he actively saved the lives of many Armenians. After Christoffel’s return, he stood by his side in the struggle to save Bethesda and supported him materially. In 1921, he was assassinated by one of his sons for his efforts on behalf of the Armenian “Gavurs” (infidels).

Mutesarrıf

Hans Bauernfeind experienced the tenure of two mutesarrıfs (district governors) during his time in Malatya. The “old” mutesarrıif, a 57-year-old Turk named Muhaf , was recalled to Constantinople on 3 June 1915 – allegedly due to an intrigue of the Vali (governor) of Mezre (Diary, 21 May 1915 ). According to a later version, he had been recalled “(…) according to a new law that stipulates that officials who hold office for more than 25 years must be recalled and first examined in Constantinople about their fitness to serve” (Diary 28 May 1915 ). The “old mutesarrıf” never once criticized the mass arrests, tortures and murders of Armenian men that were already taking place on a large scale in May and June 1915. Rather, he tried to convince his ‘friend’ Bauernfeind of the guilt of the Armenians and to dissuade him from any pro-Armenian action: “I spoke privately with old Mutesarrıf about all the cases [of arrests]. He strongly advised me against advocating for anyone. Everything was going according to the enacted laws (…) “ (Diary, 1 June 1915 ). Bauernfeind maintained a very close relationship with this mutesarrıf: he visited him and his wife regularly and affectionately called him “our mutesarrıf.” When the Bauernfeinds stopped briefly in Constantinople on their way back to Germany in August 1915, they nevertheless found time to visit “their mutesarrıf” twice.

During the short interregnum until the arrival of the new mutesarrıf, the kaymakam (district administrator ) of Arrha (Arga), Vasfi Bey, conducted the official business, which consisted mainly of organizing the mass arrests and murders of Armenian men. It was to him that Bauernfeind addressed his protest letter of 9 June 1915, in which he objected to the arrest of Protestant Armenians and to ‘excesses’ in the arrests in Malatya.

When the new mutesarrıf finally arrived from Constantinople on 20 June 1915, there were already “(…) hardly any free Armenians (…)” (Diary, 23 June 1915) in Malatya. This act of the Armenian tragedy was over in Malatya. It was now incumbent upon the new mutesarrıf to murder the Armenian prisoners and labor soldiers and to carry out the deportation of the rest of Malatya’s Armenian population.

The new mutesarrıf, a 45-year-old Kurd, arrived from Constantinople with his wife and five children. Right after their first, brief meeting, Bauernfeind was taken with him: “I did not dislike the new mutesarrıf (…). He is not one of the modern chatterers, but obviously a man of inner education and serious outlook on life” (Diary, 22 June 1915). After the second meeting, Bauernfeind, already more euphoric, wrote: “We liked him again very much. Earnest , friendly, manly, polite and educated from within, warm German friend. He comes from a distinguished Kurdish family from the Muş region” (Diary, 23 June 1915).

Bauernfeind’s enthusiasm for the new mutesarrıf was not dampened by the fact that his term of office included the mass murder of Malatya’s male Armenians, including those of his associates Krikor and Garabed. The psychologically skillful official easily managed to wrap the naive and obedient pastor Bauernfeind around his finger and influence him: The mutesarrif was infinitely sorry that “(…) the whole [Armenian] people had to suffer for the sake of a few guilty people, but as long as everything had not come to light, the greatest leniency lay in severity. He implored us to help him, to tell him everything we thought and knew. (…) for the sake of truth and justice he would do his duty” (Diary, 24 June 1915). A few days later, the massacre of the Armenians of Malatya began. Hans Bauernfeind wrote in his diary that the mutesarrıf was “ashamed of himself” but that he was “completely in the hands of the people” (Diary, 2 July 1915).

On 10 July 1915, the mutesarrıf prepared Bauernfeind for the imminent deportation of all Malatya’s Armenians to “Urfa” by dishing up a new Armenian conspiracy legend. Bauernfeind had great sympathy – for the mutesarrıf: “He made a seriously ill impression. (…) the whole man within the short time of his being here completely exhausted and broken” (Diary, 10 July 1915 ).

This deliberate ignoring of the obvious connection between the events in Malatya and the responsibility that the Mutesarrıf, as the highest official in the city, had to bear for them, determined Bauernfeind’s attitude until his departure. “The matter is becoming clearer and clearer to us that the mass murders and other illegalities occurred only during the time of the deputy and still staged by him, in the days of the serious illness of the Mutesarrif“ (Diary, 5 August 1915). Bauernfeind’s final impression: “A strict, just, incorruptible official (…)” (Diary, 11 August 1915).

With regard to the assessment of this Mutesarrıf, there is a clear contrast between Bauernfeind’s statements and those of Christoffel: For Christoffel, the Mutesarrıf was not a “warm German friend” but a member of a “German-hostile clique” and “hostile to Germany and Christians” (Saat, p. 20).

Commander Nadin Beg

The gendarmerie (zaptiye) commander of Malatya, described by Bauernfeind as a ” (…) fine, cheerful and yet serious man (…) “ (Diary, 26 May 1915), directed the arrests and torture of Malatya’s Armenian men until his recall to Mezre on 17 June. On 6 August, he returned ” (…) increased in rank to Malatya” (Diary, 8 August 1915 ).

Other

Mary Louise Graffam

(11 May 1871 – 17 August 1921)

The American teacher appeared in Hans Bauernfeind’s life and diary on 21 July 1915. She was an employee of the American mission in Sivas and accompanied the Sivas Armenians on their deportation train. In Malatya, she was barred from going any further. M. Graffam remained in Bethesda and was prepared to continue running the home after the Bauernfeinds left. But the mutesarrıf curtly forbade her to remain in Malatya. She therefore traveled with the Bauernfeinds to Sivas and stayed there to care for Armenian orphans at the Swiss Orphanage, by then run by the American Mission.

Bauernfeind entered in his diary on 17 August 1915: “Miss Graffen [sic!] was also with Vali yesterday. (…) He does not want Miss Graffen to travel with us to Constantinople now. She should stay here [in Sivas] for a while: he wants to come to her and settle the matter of the orphans with her” (p. 119f.). When Ernst Christoffel traveled home in February 1919, he met her, the “present head of the American mission station” (Tiefen, p. 92) still in Sivas: “Miss G.[raffam] was overwhelmed with work. She was alone in the station. After the opening of the orphanage, scattered Armenian orphans accumulated from all over the district. Soon there were several hundred, and new ones were arriving daily” (Christoffel, Tiefen. p.92)

Mary Graffam recorded her experiences in Turkey in 1919.[13] Her description of the deportation of the Sivas Armenians, whom she had accompanied to Malatya, gives a completely different picture than the one conveyed by Bauernfeind. She writes of mass murders and mistreatment already on their way to Malatya. It will probably remain uncertain whether she herself considered it appropriate to convey a harmless version to Bauernfeind, or whether Bauernfeind intervened in a censoring manner.

She also described her three-week stay in Malatya: “The governor in Malatya ordered Miss Graffam to appear before him. The following day she helplessly looked out from a nearby orphanage and watched as her girls and people filed by. (…) For three weeks, Mary L. Graffam remained in Malatya, which she thought to be the counterpart of the worst description of hell. The sights were terrible. At first, the Turks murdered the Armenians in the street. There was so much blood, though, that they strangled the victims with ropes and took them away at night. They left most unburied. Every afternoon, two or three thousand Armenians passed Miss Graffam’s house. She kept carbolic acid on the window sills to keep the stench of the dead from drifting in the house. The sky was black with birds and there were hosts of dogs, feeding on the bodies. ‘You could tell,’ she added, ‘where a massacre had taken place by the migration of birds and dogs.’”[14]

Witness against his will: Hans Bauernfeind on the genocide against the Armenians

1- Disarmament, house searches, arrests, torture and massacre of men

2 April 1915 – (…) Earlier an Armenian priest was here (representative of the Vardapet). With him, of course, we talked about war, mobilization, etc. Of the 700 Armenians who were drafted in Malatya, more than 150 are already dead, mostly as a result of diseases, i. e. lack of care. Appalling conditions! (…) (page 3)

16 April 1915 – (…) Last night Garabed [Karapet] (our cook and buyer) came back without a gun. He had been put in jail in the morning with a bang, his rifle and sidearm had been taken from him, he had not been given anything to eat all day, and when he wanted to go to the privy, he had been given a zaptiye. His superior was in Arshadagh [Akçadağ], and his deputy claimed to have received a telegram from Adiaman [Adıyaman] saying that Garabed had to leave for there this morning. So that he would not escape, he thought it necessary to lock him up, all without offering any opportunity to give notice. Thus, he would have been deported directly from the prison to Adiaman this morning if his commander had not returned last night and pointed out that, because he had been placed at the disposal of the Germans, he could not be sent away without first submitting the matter to the Mutesarrıf. So, he was released in the evening. (…) (page 6)

19 April 1915 – (…) A new decree has arrived according to which Armenians, i.e. Christian Ottoman nationals, are no longer allowed to carry weapons at all, but may only be used for work. Gar(abed) therefore cannot continue to be Zaptiye, but the government can use him at will for its purposes. The commander made us the extremely kind offer to put Garabed completely at our disposal. However, we declined with thanks, partly in order not to take up too much of the government’s time, but especially for our and Gar(abed’s) sake, because there is not enough work for Gar(abed) now. If we were to employ him again, there would infallibly be quarrels and jealousies, and Gar(abed), although his whole family enjoys free station here and he was not sent to war only for our sake, would silently base salary claims on it. However, we have asked that Garabed remains here, that is, that he not be sent away, and that he be placed at our disposal as often as we need him. This was gladly granted to us. (…) (page 6 f.)

4 May 1915 – The government seems to have lost all confidence in the Armenians. When we visited Khosrov Efendi (pharmacist, house friend) on Sunday, the old mother, whom we met alone at home, told us that the government had organized house searches in many Armenian houses, including theirs. They are looking for weapons, books, newspapers, letters and fugitives. Several arrests have already been made. The Armenian population is understandably aroused. (…) (page 7 f.)

10 May 1915 – (…) One thing is for sure: the government is conducting strict house searches here, proceeding in an indecent manner, which must arouse bitterness among the people. I was in the city, the Armenian people are agitated and fearful. The worst are the women, who let their evil tongues work and cannot distinguish truth from lies. (…) (page 9)

16 May 1915 – The house searches and arrests continue. A very good girl [Veronika], Sabbathist (Bonapartian family), has been led captive to Mezereh because some written Armenian songs composed by her preacher have been found with her. As far as we can judge the matter, a quite harmless thing and a cruel abuse by the government. The desertion has degenerated into a kind of hide-and-seek with the government. One of our men, stonemason Megrdich Varbed [Mrktich Varpet], was found here a few days ago in the course of a search for weapons, as a result of the testimony of a child, in a storage box, after having been in hiding for 7 months. A cousin of our acquaintance Bardrian, Yedvard, was captured the day before yesterday with some friends. Such people are then held captive for some time, sent to Mezereh, etc., until they repeat their game. (…) (page 9)

17 May 1915 – (…) The girl (…) is to be sentenced to three months in prison. The songbook in question contained two revolutionary songs. She had bought it from a 24-year-old man. The latter went unpunished because he was officially registered as 16 years old. This practice of reducing age is a common bad habit in this country. It is intended to be advantageous for military service. The girl had added spiritual songs in handwriting behind the existing songs. (…) (page 12)

According to the latest rumors, as has often been told, Dr. Micael [Mikael] is again in prison in Erzurum. Prof. Samuel [Tamrazian], son of the local Badveli [protestant preacher], who studied music in Charlottenburg [Berlin], was here for some time the other day and is now back in Harput, is also said to be imprisoned. Now the 18/19 year olds are also to be drafted, this would also affect Kirkor [Krikor or Grigor]. (page 12)

26 May 1915 – (…) The Müfettiş [inspector; deportation inspector?] from Constantinople, who is here and lives at Haşim Bey, is the most pleasant, finely educated and manly Turkish official we have ever seen. One just felt like being with a fine German official, such as a school councilor. (…) A downside to the above: The arbitrariness with which almost every day some Armenians are imprisoned and put on trial for no apparent reason, yesterday twelve, including the pharmacist Khosrov Ef(endi), begins to alienate us more and more. – Krikor is to be written as a soldier at the efforts of the Muhasebeci [Council of Accounts], but for the workers’ group and in such a way that he will be made available to us as a worker. The matter is in the hands of the gendarmerie commander. (…) (page 12 f.)

27 May 1915 – I had hardly been to the commander yesterday when Krikor was also brought to the regiment to be written up as a soldier there immediately and without the slightest difficulty. He was immediately transferred to us for any use, and is only to pick up his three soldier sandwiches every day. He is happy, his parents even more so, of course. And for us it is also extremely favorable. It is true that Krikor had given cause for many complaints in the last time, but he is now, of course, taking it very easy, since he is completely in our hands and knows quite well that if we dismissed him, he would be sent away immediately. (…) (page 13)

(…) Now the government must also have the poor searched, whereas up to now all the strict extortion measures – imprisonment, beatings, etc. – were applied only against the “better” classes. Weapons are also dug out of the fields. The Armenians betray each other. (page 13 f.)

28 May 1915 – (…) The Muhasebeci asked today to be allowed to stay with us for eight to 14 days with his family. The reason he gave is as follows: he lives opposite the prison; Armenians are now beaten up there every night, apparently often excessively, because a rather old Armenian priest (Catholic) has died as a result. They could not bear that anymore. (…) The violent measures against Armenians naturally, since the justified distrust is there, also often hit innocent people, although we have no proof for it so far. Because the rumors among the people …., well, one could write books about it! But it seems to happen that people secretly buy guns in order to be able to deliver some, if they are to be forced by beating and prison to it. (page 14 f.)

31 May 1915 – (…) The girl is sentenced to one year in prison. (…) In any case, the girl is to be kept in solitary confinement, not together with the mostly horribly depraved other women. The case is considered so serious because the girl’s brother is supposed to have gone over to the Russians, about which the mother said nothing. After all, one can no longer believe anyone here. (…) (page 16)

9 June 1915 – Today we called up the Armenian city doctor and let him tell us about everything, especially about the case of Khosrov Efendi. The latter had actually tried to poison himself, had taken a huge can of morphine, had also tried to cut his wrist with a piece of tin. Just in case, he also had strychnine and arsenic with him. The city doctor, who was quickly summoned, was just able to save his life. Reasons: “My people throw all the blame on me; the government doesn’t understand me and won’t believe me; so I don’t want to live anymore either.” Certainly, the nameless fear of beatings also played a strong role. However, these were often said to be inhumane. When people are beaten half to death, they are thrown into the water until they regain consciousness, then beaten some more. Strong village people beat, and only policemen are present, no higher official. Some people are said to have been taken home for fear that they would die as a result of the beating, as had happened once. Three people are said to have disappeared mysteriously. It is said that they were thrown into the Tokhmasu (tributary of the Euphrates) at night, but this does not seem credible to us. – According to the description of the city doctor, the prison is a room of about 160 square meters, low, dark, damp, with only a tiny air hole in the ceiling, in which 200 Armenians are currently locked up. There is also a small courtyard with a well and a privy. At night, the prisoners wash their needs in a tin container inside, which is poured out in the morning. (…) (page 20)

(…) At the farewell of the Müfetiş [deportation inspector] in the courtyard of the school, all the leaders were present. He showed there a number of a criminal magazine with pictures of masses of guns, bombs and the like, which were said to be found among Armenians in Kuharea [Kütahya], Diyarbekir, etc., and were gathered in individual rooms. The deputy of Mutesarrıf also told me that 5000 bombs were found in Mezereh yesterday. The Turkish people are becoming more and more agitated against the Armenians; the atmosphere is extremely tense, but open hostilities are not noticeable. (…) (page 20)

14 June 1915, morning – (…) Gabriel Efendi, the lawyer, has been in prison again since yesterday. I was just with Mustafa Ağa. He is completely under the influence of his Armenian entourage. He repeatedly assured me that the government secretly disappears 3 or 4 prisoners every night, who are beaten to death or thrown into the water. They would be taken away in his car. A priest, relative of Dr. Micael [Mikael], is said to be dead, as well as a certain Bonchüklian; we knew both of them, but have no definite news yet. The women come to the prison to bring food, then learn that it is no longer necessary, but get no further news. We explain the fact, which in itself seems somewhat mysterious, that the corpses are not delivered, but buried secretly, with the fact that in the other case the dead are revered as martyrs and saints and possibly unrest would arise. (…) (page 28) The excavations are strictly handled, but the Armenians are only used for work. (…) (page 29)

15 June 1915 – This morning women came again, howling, imploring: No more food is accepted for the prisoners, the clothes would be sent back; so many are dead, of course secretly killed. Although we do not yet understand and know the true facts, we naturally consider all this to be empty rumors, because we have experienced all too often that the most outrageous, stupid allegations and news are spread with all certainty. If I wanted to tell all this, I would fill volumes. Of course, I don’t want to go to the commander all the time either. The Badveli urged me to go with him to the prison and preach to the prisoners. Of course, this is quite unthinkable. Today the Turkish released prisoners, 250 in number, left for the war as volunteers, with a great show of accompanying people; horses, drums, singing students. (…) (page 29)

16 June 1915 – (…) That prisoners die and are buried secretly seems to us now to be certain. We do not believe, however, that the government is assisting in this dying; that it is not turning over the corpses (so far, by the way, only two or three cases are reasonably certain to us), we understand; for a huge excitement would go through the city if the corpses were put on display. We have now found out where they are buried.

At first, I thought that Krikor’s observations in this regard were null and void, but yesterday I found out for myself the following: At the southern tip of our field 11, where on the hillside the Khorata water ditch turns to the north (see our plot plan), five men were working on one of the trenches left over from the military exercises. When they saw me coming up with Krikor, they suddenly abandoned their work and moved away in a conspicuous hurry. But when we walked resolutely toward them, they did not continue to avoid us, but greeted me with great courtesy and kindness. They were eager to dissuade me from the intention of inspecting the work of our people at the water ditch above – we were watering. I should not bother to go up there in the heat (…).

I asked them what they had to dig in our field. I had hardly uttered the sentence when they already answered in suspicious haste and readiness: “Nothing, nothing.” I said, “Yes, but you are not digging there for nothing and nothing again?” They then said, sheepishly passing over it, they were burying some disgusting things from the hospital. Now lately rags and bed scraps and the like from the hospital have often been dumped and burned all over the place. But in this case it was obvious that it was a lazy excuse. Because 1) why this secrecy, 2) an unmistakable smell of decay came out of the hole, which showed some waste of a harmless kind at the top. And they would hardly bury an animal with such care and secrecy. Besides this hole, which was right on the water’s edge, there is one a distance to the east, as far as I could tell, within our borders. There they had just begun to work. At night, as the clover garden was being watered, Khoren and Krikor observed the following: Four people arrived with spades, one of them on a packhorse. They went to the place in question; sounds of stones and the like were heard from afar; after a quarter of an hour they returned. When they passed Krikor, who was carrying a lantern, one of them asked him sternly, “Why didn’t you tell us that there were people here?” to which Krikor replied, “You saw the lantern after all.” After all this, it seems very likely to us that the deceased Armenian prisoners are actually buried in the field. Shocking, but finally not incomprehensible and adapted to the oriental conditions. (…) (page 31)

23 June 1915 – In the meantime, both Bardrian and Nishan and other people are put in prison, so that now there are actually hardly any free Armenians here. (…) (page 35)

24 June 1915 – At 11 1/2 o’clock I went on horseback to the Khorata ditch adjacent to the southwest corner of our plot 11 (…), on the mending of which Garabed, Khoren and Krikor are working. On the way back, I rode past the (…) grave sites and observed at the westernmost one that new earth has been piled up there since yesterday. According to this, the report of our gardener (Turk) that the dogs were scouring out the bodies of the Armenian prisoners there seems to be correct. In the second hole I saw to my greatest horror how the skull and the back of a corpse, still covered with decomposed flesh, protruded, obviously dragged out at night by the dogs – perhaps ours as well. An hour later I was sitting with Khoren at the Mutessarrıf’s apartment, whom I had immediately asked for a secret interview on an important matter. I gave an accurate report of all my observations and subsequently had a meeting with him for almost two hours on the whole Armenian affair. First of all he sent a Zaptiye to the place, but he was obviously anxious to whitewash the matter (there had been a horse gifted there and perhaps one from the hospital), because he was certainly involved in the story. What I spoke with the Mutesarrıf and what I told him, I do not need to reproduce after all previously written; only from his explanations I want to record at least the most important points. What had happened before his time, he could no longer change; he did not say that nothing unlawful had happened; he even hinted that at the instigation of some rich people the Mutesarrıf deputy had helped some to die. On my urgent request to at least inform the poor women about the whereabouts of their husbands, he said that they could not do anything about it, because the matter was not pure. As long as he was at his post, he promised me on his honor that such illegalities would never occur. Even now, the prisoners should have permission to have beds and food sent to them from home, to be visited, and to go for a walk in the prison yard. He could not release anyone, however, and would have to put even more in prison until the hidden bombs and explosives were found, the existence of which was not in doubt. (…) (page 33 f.)

25 June 1915 – (…) I was about to visit Mustafa Ağa, but met him on the way at the Köşk [Mansion] of Mutesarrıf, where I talked to him a little. He said that during the night, following my intervention, the bodies buried in the six holes were properly buried. There were more than a hundred of them! (…) Mustafa Ağa also claimed to know for certain that the other day a detachment of Armenian laborers, who were engaged in road work at the Çiftlik [farm] between here and Tsoğlu on the Euphrat, were picked up on the way by the released [Turkish] prisoners mentioned on page 29, shot and thrown into the water. We had heard such rumors before, but had never taken them seriously. However, we were immediately surprised that all these people were immediately armed here, although they were robbers and murderers. And the fact is that no news has yet come back from the workers in question, who are supposed to have been sent elsewhere. Our nerves are being severely attacked by all these sinister results; moreover, we and our people are now personally endangered. We have to be very careful. (…) (page 35 f.)

2 July 1915 – The most horrible, most appalling thing has happened: Massacre. (…) When I was at the Mutesarrıf, suddenly all the workers (probably 100 to 200), who had just gone to Indärä [?] with donkeys, pipes, tools and the like for the water pipe work, came back. A short time later, soldiers were observed going up to Indärära from here, and an officer on horseback, most likely the gendarmerie commander. We also understood these strange events only yesterday. (…) (page 40 f.)

Since we started July with a possession of 1.25 piastres (about 30 pennies) and our last money (borrowed from Khoren, by the way) had been with Garabed, I decided the next morning, that is, yesterday morning, to go to Mustafa Ağa (mayor) and ask him to lend us five Ltq. I went early with Khoren and the Zaptiye and met Mustafa Ağa alone, so that we could talk more freely for once. After the necessary initial conversations, I asked if he did not know where Garabed was. He was sent to Mezereh, was the answer. After I had told him all my impressions, I said that we were worried that something else had happened. He replied: “Don’t tell anyone else, they killed Garabed, and not only him, but 300 the night before and 180 the night before.” All of them were taken to Indärä and there – I didn’t want to ask whether they were strangled or slaughtered, because we would have heard shooting. It must have been all the prisoners, that is, almost all the men who were still here at all. In the morning they are all buried there. It is quite certain that Krikor is also among them; it had already been said that he would be “sent somewhere else.” This seems to mean, according to the present usage, “to kill”, while “to go” means to die, i.e. by force. (…) (page 42)

(…) Garabed, by the way, is said to be killed especially, in the government [administration, administrative building]. He must have had, as now came out, the last days already death suspicions. (…) (page 43)

(…) We also thought a lot about Mezereh. If at all possible, we wanted to go to Mezereh with the whole house. But on the journey we would undoubtedly be attacked; it would only be possible if the government helped and protected us. However, the government cannot and must not do that under any circumstances. Mustafa Ağa also immediately took away all hope; the Mutesarrıf would not let us; we would be safe here. By the way, Mezereh, Sivas, Erzurum, Erzincan, Kayseri, etc. are supposed to be just like this. It was an order from above, of course, carefully prepared. That is why there have been no Turkish visitors for such a long time, that explains the words of the Mutesarrıf, as quoted on pages 34 and 35 (…), that is why all the remaining men and also the boys, whom the Mutesarrıf had once released, have been hastily imprisoned. How horribly we have been deceived and betrayed, with satanic malice and cunning. Not the whole government, not at all; but it is under the mob rule. (…) When this Mutesarrıf came, the matter was certainly already stirred up under the representative to such an extent that he could no longer go against the tide. Four, five people are said to have led everything. (…) (page 43 f.)

4 July 1915 – (…) According to Habeş’s statements, only 80 percent of the Turkish people agree with the measures against the Armenians. – Last night at 1 1/2 o’clock Khoren and Sarah heard two wagons driving one after the other (or one twice) to the hillside, obviously again new killings and burials. In such a wagon there will hardly have been less than 10 to 20 corpses. The killing is supposed to be over now; according to our experience at least 600 to 700. There are still about 40 workers left, who are making pipes for the industrial water supply. But they are sure that they will live only as long as their work lasts. Aaron and Mkrtich Varbed are said to be still alive. – (page 48)

5 July 1915, 11 o’clock in the evening – Before I went to bed this morning, that is, last night, I once again made the usual round on the upper Eyva. There I heard the eerie creaking of wagon wheels in the field and realized: they are driving bodies anew to the grave sites on the hillside. After about a quarter of an hour the sound came again and was lost in the orchards. Mihran then heard the same process again later. Habeş heard there were four Catholics killed, brought in one wagon only two bodies at a time. (…) (page 49) (…) The following uncontrollable rumor circulated about Krikor’s whereabouts: He was still seen in the Han [inn] last Tuesday evening. Two groups had been formed from the Armenians (labor soldiers) there, one was to finish the water pipe work here, the other, to which Krikor was assigned, was to be sent somewhere to pick wheat. A zaptiye would have said: “I am surprised that the Germans could not free you from our hands.”

This group was then transferred to prison and was seen again late in the evening being taken away from there to an unknown destination, supposedly for harvest work, but in reality probably to be strangled in Indära. That was also a harvest – the reaper’s death. These details are probably only legend. But as the only thing we heard, I wanted to record it. Apart from all the horror, all the unearthly and all the misery, which constantly weighs on the soul and sets the nerves in turmoil, what has wounded our hearts most deeply is this unspeakably mean and vile betrayal, which our “confederates and brothers” have committed against us, which has cost Garabed and Krikor their lives, us the workers, on whom our work depended for the most part, and above all every trace of trust in the government and prestige and respect among the people. (…) We work with our people for this country and people, we offer all our influence for the reassurance of the people, we try hard to appear above and below as witnesses of the truth; the thanks a double deadly blow. We stand as betrayed and as traitors. (…) (page 51)

7 July 1915 – (…) The night passed without incident. As long as I was awake, nothing at all was heard; afterwards, noises were heard as if a crowd of people had gone to Indära. But this may have been based on a deception. (…) At half past ten, Mustafa Ağa, the mayor, suddenly arrived. We were able to learn the following from him: He said that the number of Armenians killed here in the last 15 days was over 2000 (two thousand). Most of them were buried in Indära (for fear of us no longer up here on the mountain slope), about 150 at Taştepe, 250 at the Kundebeg side. The deputy of the Mutesarrıf, the Kaymakam of Arrha [Vasfi Bey], had the main blame. In his time, quite a number in the government [building] had already been killed with blows and welts! (…) Now one of the main makers was Haşim Beg and his sons (…). The Mutessarif (…) had not been able to do anything about it; everything was in the hands of four, five people. Now he is still working to ensure that the women are allowed to stay here. By the way, Haşim Beg told us the other day, when he (…) was here with his black adopted son, a bad person, that if such things (i. e. butchery) happened, it would be through the mediation of a great man, such as me!!! – By the way, the minister [Talat] in Constantinople gave orders to act against the Armenians. This happened in many cities as well as here, among others also in Diyarbekir. In Mezereh, the Vali did not allow it. He sent the Armenians, men and women, to Urfa and telegraphed to the local Mutesarrıf that he would send people to meet them. The latter replied that he had no reliable people. When Mustafa Ağa offered himself, the Mutesarrıf would not let him. In general, Mustafa Ağa is hated and endangered as a “gavur” [infidel] because of his Christian friendship. Today, 200 Armenian women had been with him. He had advised them to refuse to leave. – Exiles from Sivas had been thrown en masse into the Tokhmasu, tributary of the Euphrates, three hours from here. Empty wagons then came here in the night. (By the way, the night before last we also heard the sound of many wagons coming from the Sivas road). This is what would happen to many more. – Mehmet Beg gave the horse of the killed (…) city doctor to someone in Mezereh. The horse of the Catholic bishop who was killed during the night was given to Mustafa Ağa, who rode it today. The Mollah, who belongs to the Parliament, and who has been here many times and very amicably, spreads the opinion that the goods of the killed Armenians belong to the Turks by right. The Mutesarrıf is said to fight against it in vain. (…) Mustafa Ağa asked: “Doesn’t Europe intervene against this? Is it written in your book or in ours? If it is asked, the whole truth is written here,” – pointing to his heart, – “I am not to befrightened.” (…) (page 53 f.)

8 July 1915 – (…) To the above comment one more thing, which was also told today Makruhi: Of the workers who worked in Çiftlik, some have already been transferred from the Han [inn] to prison! How appalling to think of all the people to whom nothing was further from their minds than political machinations, with whom we consorted and whom we always reassured that they could not be in any danger, especially at this time, like Bardrian, Mikael Efendi and son, Gabriel Efendi, who worked tirelessly all his life as a lawyer in the service of the government, the Badveli, whose greatest concern was to lead people to God in this time of need and to guide them to pray, who, even close to his arrest, would have liked to talk to us about bringing God’s word to the prisoners; and Chosrov Efendi, Nishan and many others, too, had not committed any political offenses worthy of death. These people were now all locked up in prison and strangled and buried somewhere at night. One cannot believe it. – It is quite incomprehensible to us that we did not foresee all this. (…) But we are grateful that we did not suspect it and think that God kept our eyes. Because if we had known it, we would have had to stake our lives for that of the Armenians – and in all probability in vain. (page 56 f.)

2- Deportees from Sivas and Mezereh / Harput; preparation for deportation from Malatya

2 July 1915 – (…) Yesterday afternoon Haşim Beg, our neighbor, came. (…) The only thing he said was: the Armenians would all be sent into exile in the Urfa area. If it is carried out completely, by the way, an unspeakably cruel – and unnecessary – measure. (…) But the execution of the punishment corresponds completely to the moral and intellectual low of the country and appears in individual cases as infinitely cruel and arbitrary. For this reason, too, it must be decisively called a massacre, even if, in contrast to the one of 1895/96 in the form of a large-scale judicial murder, which is presented to the public as a patriotic necessity and covered up with the example of the Germans in Belgium, with hardly a shred of justice. – (page 44 f.)