“And therefore, the kazas of the Van sandjak were the following: Ardzge/Adilcevaz, Ardjesh/Erciş, Pergri, Gevash/Gevaş (historically Vosdan/Reshdunik including the Gardjgan and upper Gargar nahiyes), Mahmudiye or Khoshap (Karasu nahiye), Norduz (historically Antsevatsik, renamed Mamuratul-Reshad in 1913), Shadakh, and Van.”[1]

Labor Migration from the Van Basin

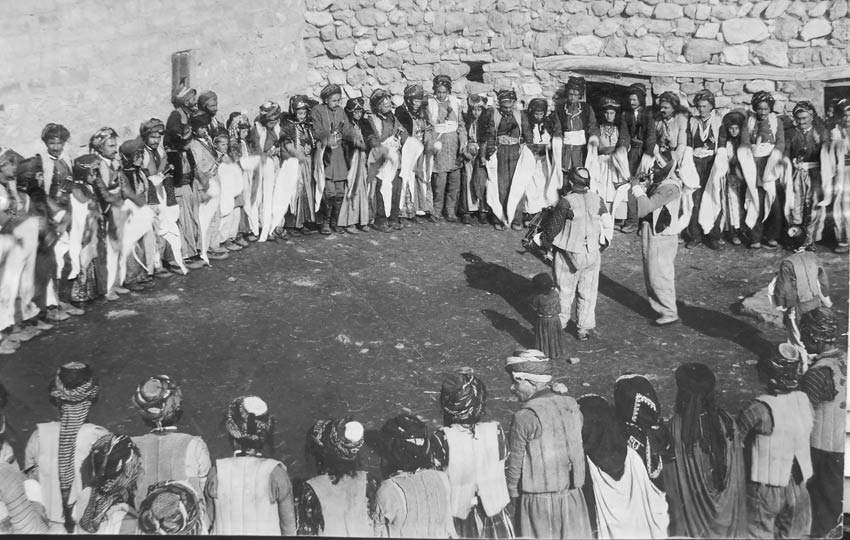

Since the 1870s and in particular in the aftermath of the Russian-Turkish War of 1877/78, of continued looting and misrule by local Kurdish chieftains, the Armenian peasantry of the Van plain suffered from starvation. The 1878-1881 famine was known as ‘Famine of Armenia’ or ‘Famine of Van’; numerous vanetsiner, as well as Armenians from Mush were compelled hire out as cheap laborers in the Ottoman cities, especially in Constantinople; many more stranded as beggars. The dimension of pandukhts’ misery made it a topic even in foreign media. The Austrian Amand v. Schweiger-Lerchenfeld wrote as early as 1878:

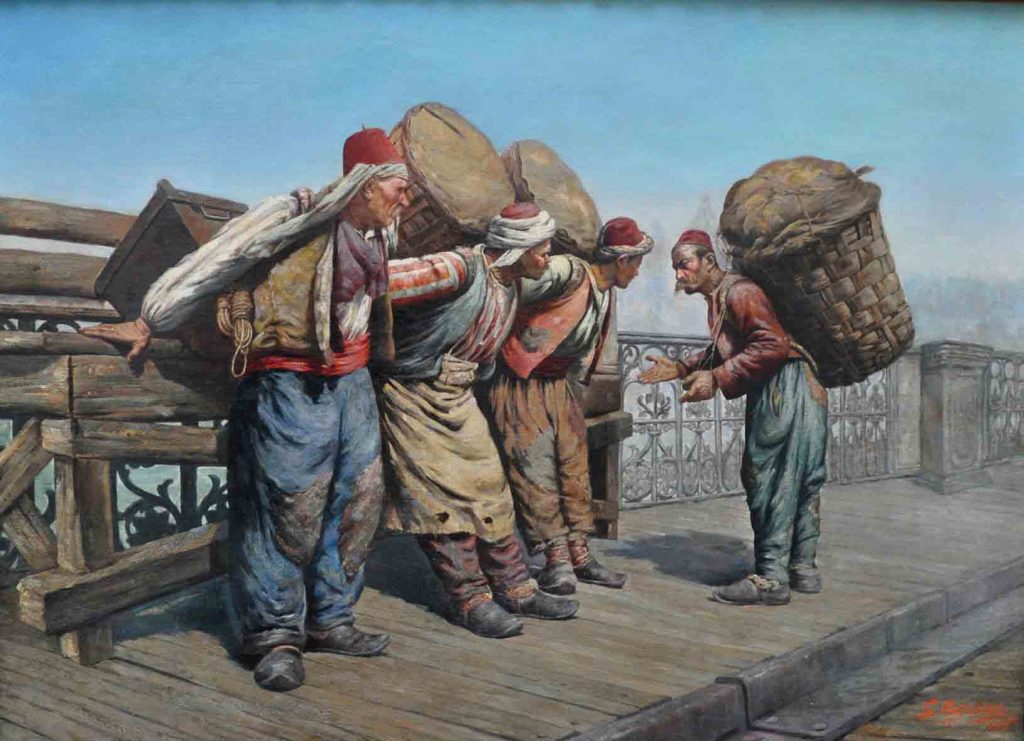

“However, even in the deepest peace, Van and its territory, with all its fertility and loveliness, cannot feed its thin enough population. Every visitor to Constantinople will remember the stocky, black-eyed figures lingering on the street corners everywhere and hiring themselves out to carry loads. They are the well-known ‘Hamals’ [2] who, with a fabulous frugality (mocha, bread and pods); individually carry loads, which could on our end be removed from place by at least three strong carriers only.

This people’s home is mostly to be found in the basin of Van.

Often 30 to 50,000 of them are supposed to eat their bread in the foreign country, and the tenth part of the same returns annually with their small savings back to their families. Whether they will find them in the same state as they left them is doubtful, after all.

But also the return of the emigrated from work is not made very joyful, because it only needs to get some tattered official to get wind of it and savings of the poor devils are mercilessly confiscated or otherwise blackmailed; the means for this are known.”

Source: Schweiger-Lerchenfeld, Amand: Armenien: Ein Bild seiner Natur und seiner Bewohner. Jena: Hermann Costenoble, 1878, pp. 103f; http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/book/view/schweiger_armenien_1878?p=135

Rev. Hans Fischer: What is the Current Situation in Armenia? (1897)

Hans Fischer ( 28 February 1869-10 July 1934) was initially a Protestant German pastor in Herborn. “During this time, he adopted the pseudonym Kurt Aram. The ecclesiastical authorities, he later wrote, had viewed his ‘belletristic leanings at the time

of the emerging naturalism with displeasure’ and demanded that he should ‘at least write under a pseudonym’; for him as a theologian it had been obvious ‘to make an Aram out of the Fisher, for this is the Aramaic translation of the good German name Fischer and nothing else’.(3) In 1900, Aram resigned from his ministry to devote himself entirely to literature and journalism. He moved to Munich, published in ‘Simplicissimus’ and from 1907 to 1910 was co-editor of the cultural magazine März [March], alongside Ludwig Thoma, Hermann Hesse and Albert Langen.”[4]

In March, Aram published a travelogue, North Persia, in 1908, from which some observations on the country and its people can also be found in his ‘Oriental’ novels An den Ufern des Araxes: Ein deutscher Roman aus Persien (On the banks of the Araxes: A German novel from Persia; 1911) and Oh Ali! (1927). Both novels and the travelogue are based on the impressions of an inspection mission to Armenia and northwestern Iran that Rev. Hans Fischer undertook in 1897 for the German Aid Society for Armenia. On 27 October 1897, H. Fischer spoke in Berlin at a public meeting, “which, however, was hushed up by the [German] press”[5] , on the subject of “What is the current situation in Armenia?”

In 1909, H. Fischer, alias Kurt Aram, moved permanently to Berlin, where he first worked as a feature editor for the Berliner Tageblatt.

What is the Current Situation in Armenia? From Hans Fischer’s lecture in 1897

“Judging by the newspapers, everything there should be back on the old track. But it is not like that. It is actually even worse today than it was at the time of the great slaughters. The motto is still exactly the same today as it was in the past: there will be further slaughter and murder! Because one saw that Europe becomes nevertheless somewhat restless, one changed the tactics. Today it is no longer a question of ‘killing 10,000 in one day’, but of ten here, twenty there, a hundred there. The newspapers hardly take any notice of such trifles! Murders continue with the same thoroughness as before; only now they are a bit more skillful. In the district of Van I have seen many things that could have been seen even by those who always think of Armenians as scoundrels. A group of girls came to our orphanage who had been hung from trees and then slowly had their skins removed from their skulls. It is difficult to imagine the condition in which the poor people were. Most of the women in our orphanage had been violated and were in an appalling mental condition. For example, it is now a popular practice to strip faithful Christians, put them in a basket with bees and put them on an anthill. It is unimaginable what becomes of such a person! I was traveling on the Turkish border and saw something dark hanging from a tree. What was it? A priest whose skin had been completely flayed off. This did not happen in 1895 or 1896, but in the last few months! It is also claimed that all the butchery was just an unfortunate coincidence. Are certain telegrams, which have been made available to us through the kindness of some pashas, saying: ‘On such and such a day so and so many thousands are to be killed’, coincidence? Don’t talk about coincidence! There is rather a higher order behind it. Recently it was said in the newspapers, ‘the Armenians are still persecuted even in Persia’. But not by Persians! It cannot be said loudly enough that the Persian government was most Christian against the Armenians. An Armenian ‘uprising’ was supposed to have broken out in Tabriz (Persia). ‘Armenians’ were shooting Turks from the rooftops. The Persian government fortunately caught these ‘Armenians’ and lo and behold, they were Turks dressed as Armenians! This is how it is done! This is how you stamp Armenians as revolutionaries! This is slyly satanic! We have to help them as human beings, as Christians, as Germans.

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 2. Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918