Administration

Smyrna was the seat of the Governor General of Aydın Province (Vilayet), as well as the seat of a Greek Orthodox Metropolitan and one Catholic, one Greek, and one Armenian Archbishop.

Toponym

According to recent excavations, the city was originally called Tismurna, with the Ti prefix probably denoting a person. Turkish historians believe that the city was named after an eponymous Amazon named Σμύρνα (Smyrna), which was also the name of a quarter of Ephesus.

In inscriptions and coins, the name often was written as Ζμύρνα (Zmýrna), Ζμυρναῖος (Zmyrnaîos, ‘of Smyrna’). The name Smyrna may also have been taken from the ancient Greek word for myrrh, smýrna, which was the chief export of the city in ancient times. Around 1930, the name of the city was officially changed to Izmir.

Population

Smyrna was a multi-ethnic and multi-religious city. Its population consisted mainly of Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic Christians, but also of Catholic and Protestant Christians; Jews and Turkish Muslims formed minorities. The population groups each lived in their own neighborhoods, i.e., next to each other rather than with each other. The rise of nationalism prevented Smyrna from becoming a truly cosmopolitan city.

In 1914, the kaza of Smyrna had a Greek-Orthodox population of 200,570 inhabitants, residing in 24 localities.[1]

Destruction

Before the First World War

“In June, 1914, the village of Bournabat [today Bornova; previously also Burnabat, Bîrûnabad, or Prinobaris, Pyrinóbaris] was attacked by a band of Turkish brigands. Miysos Tsobanis, a boy of 13 years, and Const. Chr. Carandrea were murdered. The father of the latter and his sister Gheorghitza were mortally wounded; his mother was also wounded in the abdomen and breast, and one hand cut off. On the 28th of July, 1914, Mitso Cocaliaris was killed by five gun-shots and his body was burnt; Manolis, an orphan, was beaten and nearly stoned to death. A certain Kostis Tsakiroglou was compelled to deliver his property to the secretary of the regiment in garrison under menace of being expelled.

At Boudja [Trk.: Buca], the gendarmes murdered Kostas Kokinis, a noble of Sevdi-keuy [Sevdiköy], on the 28 June, 1914, close to the railway station. At Sevdi-keuy, Constantinos Theofanakis was condemned to be hanged after being falsely accused that he murdered the mudir of the village whose bestial advances he refused to satisfy. Stamatios Soukialvanis was murdered. Panos Tzanopoulos and his brother Ghenias were mercilessly beaten by a gendarme because they refused to hand over to him their two sisters. At Bounar-bashi [Bunarbaşı], loannis Karipis and Constantinos Tzanakis were severely wounded.”[2]

“No Greek center suffered more from the hatred of the Turks than the district of Smyrna. This flourishing and prosperous district (…) was sure to feel and be more directly affected by the policy of extermination practised by the Young Turks than any other.

The unfortunate Christians of the Interior, abandoning their farms, their unreaped fields, their tobacco plantations, their vineyards full of grapes, and their valuable cattle, resorted to Smyrna in the hope of saving what was still left to them as well as their lives and honour.

- GUERENKEUY [Gerenköy].— This village was assaulted on the night of the 29th of May, 1914, by bands of armed Turks under the command of the Chief of the Gendarmerie of Menemen. It was set fire to. At first the inhabitants withstood the attack, but were obliged later on to evacuate the place and flee with their families to the village of Serekeuy [Sereköy], at a distance of two hours. There they parted, one company going down to the sea shore where they embarked for Mitylene , the other taking refuge in Menemen and Smyrna.

The Metropolitan of Smyrna, Chrysostom, demanded from the Vali of Smyrna, Rahmi Bey, the permission for the latter to return to their homes, in conformity with the promise made to him by Rahmi Bey. The Vali, however, established in the meanwhile Moslem emigrants in the village of Guerenkeuy [Gerenköy] and refused to receive a deputation of the villagers when they solicited his protection.

Therefore the second train of Christians of the village of Guerenkeuy also embarked for Mitylene.

The Church, school, and half of the village houses were burnt. The following are the victims of the fire: Evangelos Spirou Kehaya, Nasselos with his small child, Manolis Tsalapassis, Jean Smyrnadis, Panayiotis Tsoulios, Petros E. Tsouglas, Georgios Mougharakis, and G. P. Kambako. Besides these, a great number were dangerously wounded.

- SOYOUDJOUK [Suyucuk]. — Five hundred armed Turks surrounded this village on the 31st May, 1914. The brigands started firing and the inhabitants responded in defense. A regular combat ensued lasting six hours, with the result that the peasants, unable to resist the ferocious attacks of the Turks, left the village and crossed over to the adjacent islet whence they witnessed the plundering of their property and the burning of their homes. Shortly after they embarked for Greece.

- BAGH-ARASSI, and 4. BARES.— The inhabitants were expelled under the same circumstances and conditions, and resorted to Greece.” [3]

July 1914-Dec. 1915: Statistical Table of the Crimes Which have been Committed Against the Greeks

SMYRNA

July 1914. G. Paxinos, C. Paxinos, Skyrianos, Ph. Kambiris. A. Loutraris, Lalas, five brothers Tsichhi, were killed at Kiosteni.

July 1914. A. Papaioannou, G. Georgiadis, A. Christodoulou Chalkias, were killed in the village of Askioi [Asköy]; C. Orphanos, G. Tseravellis, were butchered on the road to Vourla.

Aug. 1914. Two Stamatiou brothers and their servant were killed near Ghioulhissar [Gülhisar] . Mrs. Triantaphylli and Mrs. Zacharoula Aspromati were assaulted by soldiers.

Sept. 1914. The two brothers A. and Z. Kavakioti were killed near Gali-Tekeli. G. Kagritsoglou and his son Elias were killed at Aghiasolouk. The brothers I. and E. Kontoyanni were killed at Develikioi [Develiköy]. I. Michalios, I. Tsiniroglou were killed at Kouroutseshme [Kuruçeşme]. Karayannis and Spanoudis were killed at Ouskioi [Usköy].

Dec 1914. I. Procopiou, G. Charalambides, G. Mylonas, were butchered in the village of Karaoulani [Karaulani]. Constantelli brothers, S. Samios, Karapanaghiotis and his son, Tsemeli, were murdered near Sevdikioi [Sevdiköy]. P. Tsomlotsoglou, P. Kehayioglou, D. Tsilonoglou, were murdered near Salihli; Kirkintsohs, Kaphilis, N. Krassassounis and a certain Demetrios, natives of Macedonia, were butchered.

Jan 17 1915. N. Kypriotis, was murdered near Mezikli. The prominent citizen C. Metaxas was severely wounded at Mylassa. The three brothers Manoussoglou and Karpouzas were butchered in their mills at Hotetou. Constantine Gregoriou was killed at Agatsikioi.

Jan 19 1915. P. Sklavounos, A. Karlaghinis, were killed near the village of Gheronta. Th. Corphiatis and his servant were killed at Gheronta.

Jan 22 1915. Ch. Tourtsekoushoglou and Ch. Tsomlektsoglou were murdered near the village of Gheronta. Neophotistos Georgiou was killed at Meressi.

Jan 27 1915. C. Nikolaou and his wife at Mylassa.

Jan 30 1915. Th. Kariotis was severely wounded, also Maria Psalti and her daughter, near Kirtsali.

Jan 31 1915. Th. Xenos, V. Salatso, were killed at Bournabat [today Bornova; previously also Burnabat, Bîrûnabad, or Prinobaris, Pyrinóbaris]. The priest Mamakis and Chasidakis were murdered at Halicarnassos.

Feb. 1, 1915. N. Balis at Menemen.

Feb. 5, 1915. Marigo Protopsalti was assaulted and severly wounded in the village of Kirtsali. N. Tilikos, Th. Tomios were murdered near Nazilli.

Febr. 11, 1915. C. Voudouris, D. Nidraios, I. Melios, at Vayakassi near the village of Sokia [Söke]. P. Zachariou at Mourtzali.

Jan. 12, 1915. St. Strategos at Mezarlik.

Jan. 13, 1915: Lieutenant Nouri with two other officers assaulted and severely wounded Mrs. A. Koussaki at St. George, a suburb of Smyrna.

Jan. 16, 1915. V. Moustakias was found beheaded in his house at Koukloutsa.

March 8, 1915: E. Saghior was murdered in the village of Mitochori.

March 10, 1915. G. Yiannitakis was killed at Tsapaki. I. Yioules, L. Tsemalis were murdered at Menemen.

April 10. 1915: V. Kavakiotis, E. Kavakiotis and his son, 12 years of age, were butchered at Yabeni. In the same village the two minor sons of Delimanoli were severely wounded.

May 1915. I. Lagos was murdered at Ephesus. E. Phoutounoglou was murdered near Koula. Karakalpakis and two millers, one named Costas and another of unknown name, were found dead, perforated by bullets, near Nazilli.

May 16, 1915. A. Carmeropoulos was murdered near Yeni-Pazar. Ch. Christodoulou was severely wounded by a bullet.

June 5, 1915. Ph. Namatianos was murdered at Karapounar [Karabunar].

June 15, 1915: After the bombardement at Halicarnassos eighteen (18) inhabitants and one girl, 16 years old, were slaughtered by Mohammedan Cretans.

June 16, 1915. D. Roumeliotis, D. Tagheas, were murdered at Bouyoukli [Büyüklı]. I. Milonas and his son George Kirkintse.

July 1915. D. Arghyrakis was murdered.

August 1915. A. Spyoglou was murdered at Kirkintse.

Sept. 1915: Ch. Avvopoulos, I. Hadjipetros, D. Broussalis, I. Phetsopoulos were murdered at Aktse.

Oct. 1915. C. Baindirlis, E. Karinas, D. Pathos and I. Baxevanis were murdered at Sokia [Söke]. V. Karvelas was imprisoned and subjected to terrible tortures from which he died after a few days. G. Gouvelas was imprisoned.

Dec. 1915. Five corpses which had been mutilated horribly were taken from a river near the village of Gheronta.[4]

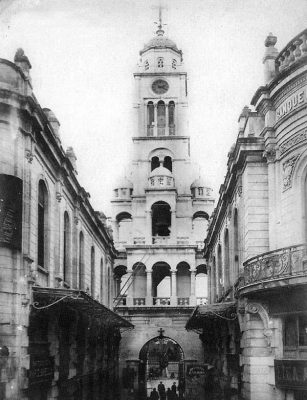

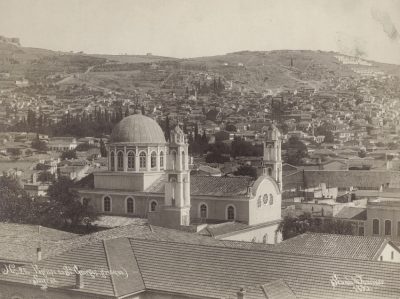

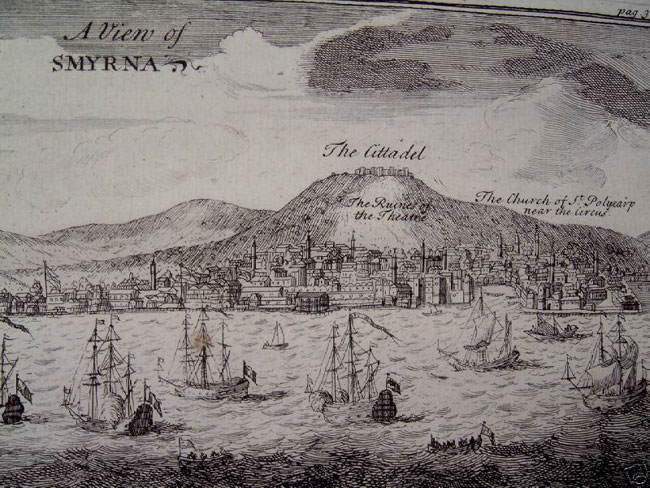

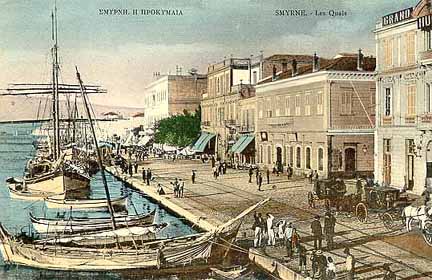

City of Smyrna

Old Smyrna was located on a small peninsula connected to the mainland by a narrow isthmus at the northeastern corner of the inner Gulf of İzmir, at the edge of a fertile plain and at the foot of Mount Yamanlar. This Anatolian settlement commanded the gulf. New Smyrna developed simultaneously on the slopes of the Mount Pagos (Kadifekale today) and alongside the coastal strait, immediately below where a small bay existed until the 18th century.

The core of the late Hellenistic and early Roman Smyrna is preserved in the large area of İzmir Agora Open Air Museum at this site.

Population

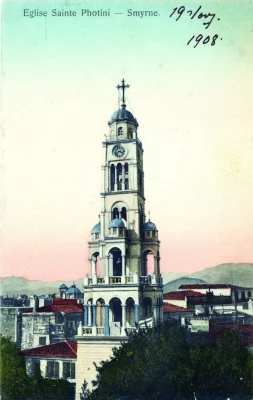

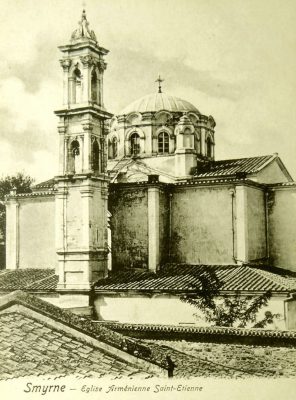

By the size of its population, Smyrna was the second largest city of the Ottoman Empire. It was at the same time a predominantly non-Muslim city, called ‘gavur [infidel] Smyrna’ for that reason by Muslims. According to the German universal encyclopedia Brockhaus published in 1841, Smyrna at that time had 19 large mosques, five Greek, one Armenian, two Catholic, two Protestant churches and seven synagogues, as well as some Greek educational institutions.The population was ethnically fragmented, for the inhabitants of Smyrna did not form an integrated community. Each group lived on its own ethno-religious island with its own educational, cultural and other institutions. In 1676, the second Armenian printing press after Constantinople (1567) was established there.

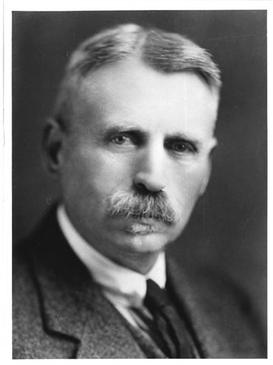

According to US-consul George Horton, “(…) it is probable that (at the time of its destruction) the inhabitants exceeded five hundred thousand in numbers. The latest official statistics give the figure as four hundred thousand, of whom one hundred and sixty-five thousand were Turks, one hundred and fifty thousand Greeks, twenty-five thousand Jews, twenty-five thousand Armenians, and twenty thousand foreigners: ten thousand Italians, three thousand French, two thousand British and three hundred Americans.”[5]

The German documentarist of the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians, Johannes Lepsius, offered much lower figures: “Smyrna has among 210,000 inhabitants only 52,000 Turks, against 108,000 Greeks, 15,000 Armenians, 23,000 Jews, 6,500 Italians, 2,500 French, 2,200 Austrians and 800 English (mostly Maltese). The dominant language is not Turkish, but Greek. Armenians have a very significant share in the trade. For the most part, imports into the interior are in their hands.”[6] Other estimates mention 30,000 Armenian residents in the city of Smyrna, where an Armenian Apostolic archbishop was situated. The Armenian community maintained four churches, severals schools, a hospital (founded in 1802) and a theatre.[7]

Based on the official Ottoman salmane (statistical yearbook), the German consulate estimated that at the beginning of the 20th century Smyrna’s overall population was 300,000 with a relative Greek-Orthodox majority of 140,000 and a minority of 90,000 Muslims.[8]

Smyrna born notable Greeks

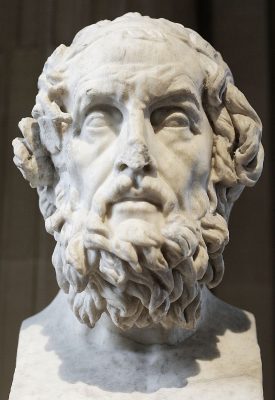

Competing with Athens and other cities, Smyrna claims to be the legendary birthplace of the Asia Minor poet Homer (8th century B.C).

- Adamantios Korais (Ἀδαμάντιος Κοραῆς, 27 April 1748 – 6 April 1833), scholar and writer of the Greek enlightenment

- Manolis Kalomiris (Μανώλης Καλομοίρης; 14 December 1883 – 3 April 1962, Athens), Greek composer

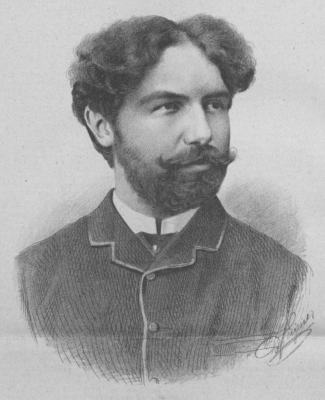

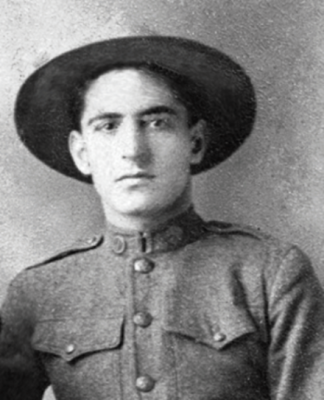

- George Dilboy (Γεώργιος Διλβόης – Georgios Dilvois, 5 February 1896 – 18 July 1918) American hero

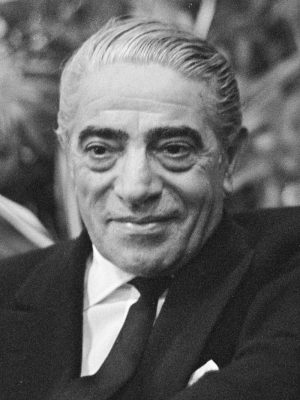

- Aristotle Onassis (Αριστοτέλης Ωνάσης; 20 January 1900 – 15 March 1975, Neuilly-sur-Seine), Greek shipowner and merchant

Smyrna born notable Armenians

- Stéphan Elmas (Elmasian; Armenian: Ստեփան Էլմաս; 1862 – August 11, 1937, Geneva), composer, pianist and teacher

History

Ancient period

Finds from recent excavations suggest that the present city area was settled 8,000 to 10,000 years ago. The city was founded around 3000 B.C. as a settlement of Lelegians in the area of today’s Bayraklı district. At times it was in the sphere of influence of the Hittites and from 688 B.C. it was an important city of the Ionians, a Greek tribe. Even today, the Greeks are referred to in Turkish as ‘Yunan’ (= Ionians) and Greece as ‘Yunanistan’.

The Lydian king Alyattes destroyed Smyrna in 630 B.C. Only Antigonos I Monophthalmos founded a new Smyrna southwest of the old city. The harbor he built laid the foundation for Smyrna’s development into one of the richest trading cities in Asia.

Having already suffered greatly during the conquest by the Roman consul Dolabella, it was further damaged by earthquakes in 178 and 180 A.D., but was rebuilt by Marcus Aurelius.

Late Antiquity – Byzantium

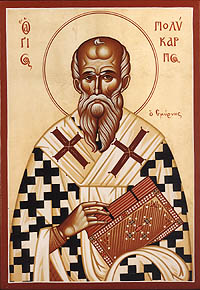

Smyrna was an important center of the Christian world. A Christian community established itself early on.

This church is one of the seven churches of the Revelation of John. The church father Polycarp of Smyrna, author of a letter to the Philippians, was a martyrized bishop of Smyrna in the 2nd century. Ignatius of Antioch also stayed in Smyrna and is said to have written four of his Epistles there.

Smyrna belonged to the Byzantine Empire from 395. In 1083 it was temporarily conquered by the pirate Tzachas and in 1402 by Timur Lenk (Tamerlan). After Byzantium had already lost the greater part of Asia Minor, Murat II conquered it for the Ottoman Empire in 1424.

Ottoman Empire

Even under Seljuk and Ottoman rule, Smyrna remained the most important trading center in Asia Minor, as well as the center of carpet weaving and the main hub for carpet trade.

Re(m)betiko (ρεμπέτικο): From Ottoman café house music and Greek Blues until UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

Although nowadays treated as a single genre, rebetiko is, musically speaking, a synthesis of elements of European music, the music of the various areas of the Greek mainland and the Greek islands, Greek Orthodox ecclesiastical chant, often referred to as Byzantine music, and the modal traditions of Ottoman art music and café music.

Rebetiko grew out of particular urban circumstances. Often its lyrics reflect the harsher realities of a marginalized subculture’s lifestyle. Thus one finds themes such as crime, drink, drugs, poverty, prostitution and violence, but also a multitude of themes of relevance to Greek people of any social stratum: death, eroticism, exile, exoticism, disease, love, marriage, matchmaking, the mother figure, war, work, and diverse other everyday matters, both happy and sad.

“The womb of rebetika was the jail and the hash den. It was there that the early rebetes created their songs. They sang in quiet, hoarse voices, unforced, one after the other, each singer adding a verse which often bore no relation to the previous verse, and a song often went on for hours. There was no refrain, and the melody was simple and easy. One rebetis accompanied the singer with a bouzouki or a baglamas (a smaller version of the bouzouki, very portable, easy to make in prison and easy to hide from the police), and perhaps another, moved by the music, would get up and dance. The early rebetika songs, particularly the love songs, were based on Greek folk songs and the songs of the Greeks of Smyrna and Constantinople“.[9]

The first rebetiko songs to be recorded were mostly in Ottoman/Smyrna style, employing instruments of the Ottoman tradition. During the second half of the 1930s, as rebetiko music gradually acquired its own character, the bouzouki began to emerge as the emblematic instrument of this music, gradually ousting the instruments which had been brought over from Asia Minor.

The majority of rebetiko songs have been accompanied by instruments capable of playing chords according to the Western harmonic system, and have thereby been harmonized in a manner which corresponds neither with conventional European harmony, nor with Ottoman art music, which is a monophonic form normally not harmonized. Furthermore, rebetika has come to be played on instruments tuned in equal temperament. A considerable proportion of the rebetiko repertoire on Greek records until 1936 was not dramatically different, except in terms of language and musical “dialect”, from Ottoman café music (played by musicians of various ethnic backgrounds) which the mainland Greeks called Smyrneika. This portion of the recorded repertoire was played almost exclusively on the instruments of Smyrneika/Ottoman café music, such as kanonaki, santouri, politikí lyra (πολίτικη λύρα), tsimbalo (τσίμπαλο, actually identical with the Hungarian cimbalom, or the Romanian țambal), and clarinet.

Rebetiko was originally the music of dispossessed Greek refugees from Asia Minor who came to Greece from Turkey in the early 1920s. In the slums around Athens, Piraeus and Thessaloniki, this music from the eastern Mediterranean was then mixed with musical traditions from mainland Greece, as well as with song lyrics that dealt with life in the urban underworld.

In 2017 rebetiko was added in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists.

Pantelis Thalassinos:

“Ta Smirneika Tragoudia (Τα Σμυρνέικα Tραγούδια)”

ο καθρεφτάκι σου παλιό

και πίσω απ’ τη θαμπάδα

η Σμύρνη με το Κορδελιό

και η παλιά ΕλλάδαΜουτζουρωμένο το γυαλί

μα πίσω απ’ τους καπνούς του

βλέπει ο Θεός το Αϊβαλί

και σταματάει ο νους τουΤα σμυρνέικα τραγούδια

ποιος σου τα ‘μαθε

να τα λες και να δακρύζεις

της καρδιάς μου ανθέYour little mirror (is) old

And behind the blur

(there is) Smirni and Kordelio

And Greece of the old timesThe glass (is) tarnished

But behind its smokes

God sees Aivali

And stops his mindThe songs of Smirni

Who taught them to you

To say them and weep

Flower of my heart.

Destruction

Before the First World War

“At Smyrna, Giovani Souvadjoglou, a foreman of the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers, Ltd., was murdered by soldiers. Near the locality of Utch-Tepe [Üçtepe], the guards of the farm of Haidar and Mehmet joined a band of seven brigands, and attacked, on July 14, Dem. Lambi Fokianou, Evangelos Tsikaliotou, and Panayioti Panas, and mercilessly tortured them. They cut off the nose and the ears of the last mentioned and the sexual organs of the third.

All eatables supposed to provide for the needs of the Army were requisitioned with such thoroughness that the peasants were very often deprived of their bread. The Vali confiscated the beautiful edifice in marble, in the very centre of Smyrna, serving as dining-room of the students, and the seat of the Astronomical Society, and established 300 gendarmes in case of fire, contemplating it is said having recourse to this means for the destruction of the town. He did everything in his power to terrorize the people, and to even set fire to Smyrna. Indeed, he threatened, in the presence of the Metropolitan of Ephesos and Smyrna, and of the town Councillors, M. Tsourouktsoglou, and Ch. Athanasoulas, to set fire to the town at the first shot fired from an enemy man-of-war. He declared that Smyrna should not undergo the fate of Salonica, which was sur- rendered to the Greeks when it ought to have been put to the flames. This declaration was made in the presence of the British and Russian Consuls.

This same attitude with regard to the town of Smyrna was also that of the Government, resulting in the systematic organization of the boycott, the oppression of the Greek population, the expulsion and persecution of absolutely peaceful persons, the violation of the communal regulations of Smyrna, and of the privileges of the Greek element. The terrorism exercised in the country until the conclusion of the Armistice constitute the many devices conceived by the Vali for the annihilation of Hellenism, and the conversion to Mahomedanism of the Greek element in these territories.

In order to facilitate the accomplishment of his scheme he devised a plan of getting rid of the spiritual Head of the Greek Community, Metropolitan Chrisostomos, in whom he knew the Greek element had such faith.

At the instigation of the Vali of Smyrna, the central Government handed to the Patriarchate under date 15 July, 1914, a ministerial decree demanding that the Metropolitan of Smyrna should be recalled. His presence there, it was stated, was undesirable, as he both encouraged the Christians to emigrate, and facilitated the departure of the Greeks of the neighborhood who came into Smyrna.

The notice of the Government was duly called to the fictitiousness of this accusation, but with no effect. Neither did the explanations furnished by the Metropolitan himself to the Vali regarding the real state of things in any way alter the situation.

On the 21st August, 1914, the Commissioner of Police, Hachim Bey, acting under the orders of the Vali, went to the Bishopric, re- moved the Metropolitan by force and put him on board the Italian boat bound to Constantinople.

The Greek Patriarchate addressed a note to the Government dated 8 October, 1915, in which the reinstatement of the Metropolitan was requested. It was not granted, however, the Government replying verbally and by decrees dated 7 January and 12 November, 1915, that his return to Smyrna was strictly prohibited. Further, that he should abstain from taking part in the meetings of the Holy Synod, and to abstain from any intercourse with his district. This illegal request of the Government was not acceded to, and after a prolonged stay in the Capital, the Metropolitan of Smyrna returned to his Diocese after the Armistice with Turkey was concluded.”[10]

During the First World War

“By the summer of 1915, the leaders of this community were feeling so jittery that they held a public religious ceremony to pray for the success of the Turkish army. One of Smyrna’s leading Armenian lawyers, Nazareth Hilmi, gave a rousing speech in which he declared the absolute fidelity to Turkey of the city’s Armenian population. According to the Austrian consul – one of the dignitaries invited to the service – it was ‘a patriotic speech that stressed the complete loyalty and submission to the Ottoman empire of the Smyrniot Armenians’.

Such demonstration had little effect on the ministers in Constantinople, who had every intention of extending their purge to Smyrna. They did their utmost to provoke Rahmi Bey into action, informing him that a court in Constantinople had ordered the death for seven Armenian prisoners being held in Smyrna. The offence committed by these men was unclear and Rahmi Bey was dismayed by such travesty of justice. Believing the men to be innocent, he wired Constantinople with the message that under Ottoman law the accused had the right to appeal for clemency. Soon afterwards, he received the answer: ‘Technically, you are right. Hang them first, and send the petition for pardon afterward.’

The seven Armenians were eventually saved from the gallows by the intervention of Henry Morgenthau, who directly petitioned government ministers. This went some way to reassuring Smyrna’s Armenian community.”[11]

But it was not only the supposed benevolence of the provincial governor Mustafa Rahmi for the Armenians of his province or the humanitarian intervention of the U.S. ambassador to Constantinople, Henry Morgenthau, that saved the Armenians of the city of Smyrna from deportation. On 2 June 1921, General Otto Liman von Sanders, as an expert witness in the criminal case against the Armenian assassin Soghomon Tehlirian in the Berlin jury trial, testified as follows about his humanitarian interventions:

“Another time I came to Smyrna. There, the Vali [Mustafa Rahmi Bey] had 600 Armenians taken from their beds in the night and put into wagons to be deported. I intervened and told the Vali: If one more Armenian is touched, I will have his gendarmes shot by my soldiers. Thereupon the matter was withdrawn. That is a fact. Also in the book of Dr. Lepsius this incident is described.”[12]

In his memoirs, Otto Liman von Sanders also mentions the outbreak of cholera:

“In the summer of 1916, cholera, which had already been occurring sporadically for months in various localities and especially on the stage roads, but which had been laboriously kept down by quarantine measures, broke out in Smyrna in a very violent epidemic and claimed numerous victims from all segments of the population during the first period.

On several occasions Greeks in Smyrna came to me, lamenting with tears in their eyes that the downfall of Smyrna was imminent and begging us to let them leave or to save Smyrna. We always tried to calm them down and promised them help. But they had to stay in place.“[13]

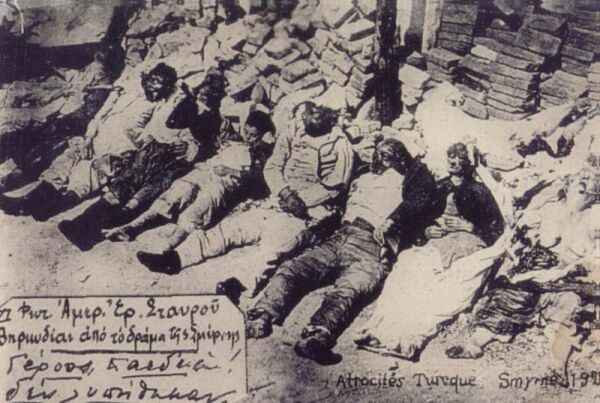

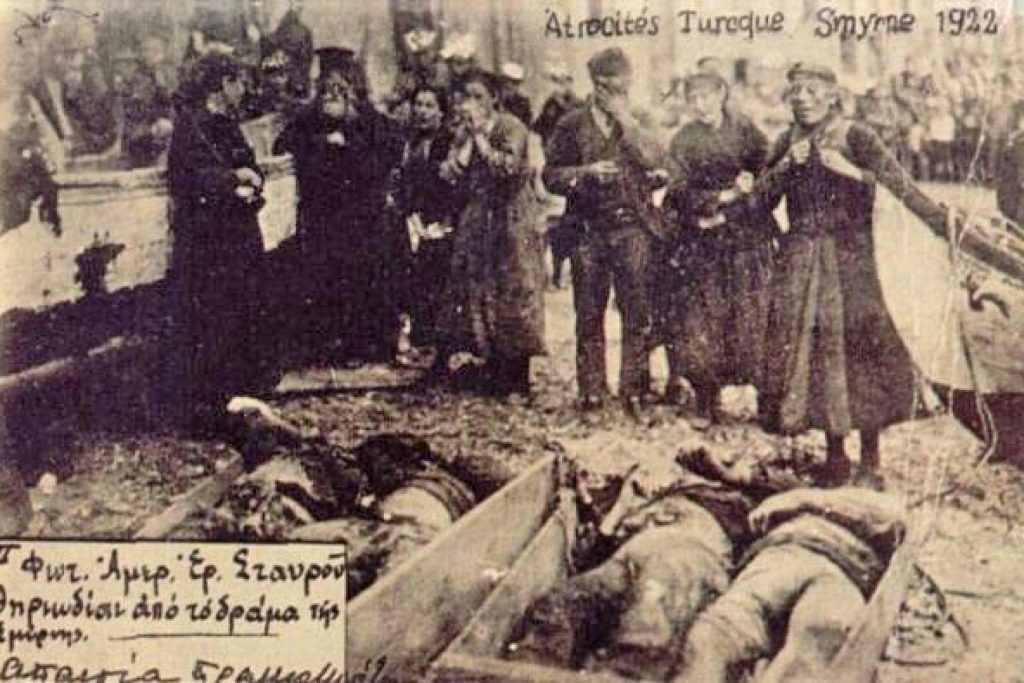

1922: The Holocaust of Smyrna

Although Smyrna was awarded to Greece in the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, the ‘Pearl of the Aegean’ and ‘Little Paris of the Orient’ became the last stage of what is called ‘the Asia Minor tragedy’ in the official modern history of Greece. Defeated by the Turkish nationalist forces, deserted by the Allies, the retreat of Hellenic forces from Asia Minor in late summer 1922 became a massive flight, joined by tens of thousands of Ottoman Christian civilians. “By the night of September 5, there were more than a hundred and fifty thousand refugees in the city. (…) It was as if the entire Anatolian landscape for hundreds of miles back from the coast was disgorging itself of frightened Christians.”[14] The Smyrna Relief Committee, monitoring the arrival of refugees by train and on foot, estimated that 30,000 people were arriving each day in Smyrna.[15]

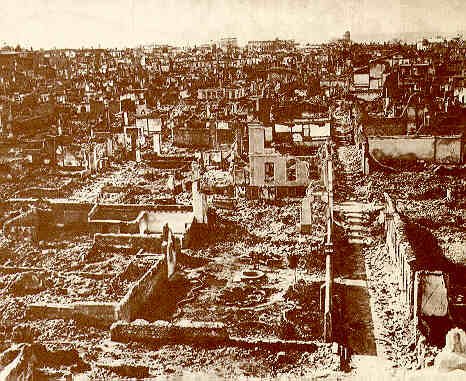

Smyrna burning, 14 September 1922, as seen from an Italian ship (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smyrna#/media/File:Great_Fire_of_Smyrna.jpg)

The Hellenic forces and administration disembarked on 8 September 1922[16]. In the early hours of the next morning, 9 September regular and irregular Kemalist cavalry under the command of Nureddin Pasha occupied the completely undefended city, and first looted and then destroyed the Armenian quarter Haynots in the north of Smyrna, before setting it on fire in the night of 13/14 September. The Armenian eyewitness and survivor Garabed Hatcherian noted in his diary:

“Wednesday, the 13th: (…). After traversing a few districts, I enter Chalgidji Bashi [Çalgıcı Başı] where there is very little activity. I see a Turkish soldier on patrol. It is obvious that the Haynots and the surroundings are under siege. (…) I continue my path towards Chalgidji Bashi, but on the passage leading from Katirdji Oglou [Katırcı Oğlu] to Chalgidji Bashi, I see a Turk who approaches me saying, ‘We did what was due; you turn back.’ The Turk, who obviously had assumed an active role in the arson, takes me obviously for his compatriot and accomplice and advises me not to advance, but to turn back. I answer, ‘Very well’, with the attitude of someone who understands the situation (…). The crackle of burning materials and the transformation of explosives into flaming clouds produce an infernal sight the likes of which I have never seen before. In Istanbul and other cities, I have seen huge fires. During the battles in the Dardanelles and in Romania, I have witnessed the burning of so many cities and villages, but none of those fires has made such a strong impression on me. The fire in Smyrna is indescribable and unimaginable.”[17]

Lasting four days, the obviously controlled and manipulated fire of Smyrna destroyed the lower parts of the city, which were Christian (European), starting with the Armenian and the Greek quarter adjacent to Haynots. Many Christians died in their burning houses or were killed by collapsing walls.

“The larger part of the European quarter of Smyrna is burning. According to an American eye-witness, Miss Mills, headmistress of the American College, the fire was started by a sergeant of Turkish regulars, who entered a house carrying tins of petroleum. Estimates of the damage caused by the fire up to last evening amount to £15,000,000. (…) It is reported here that up to the outbreak of the fire about one thousand persons had been massacred, but it is feared here that the number is now much greater.

(From our correspondent in the Near East, Constantinople, September 14th)

Fire broke out in the Armenian quarter of Smyrna and spread to the European quarter, where several Consulates and other houses have been destroyed. United States and Allied contingents were landed, but have been unable to prevent the extension of the fire, which now threatens the whole European quarter.

Athens, Sept. 13. — According to a Greek journalist who escaped from Smyrna on board the Messageries steamer Lamartine, Mgr. Chrysostomos, the Orthodox Metropolitan of Smyrna and the Gregorian Armenian Archbishop have been murdered. — Reuter.)”[18]

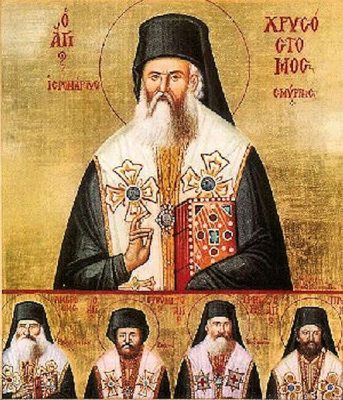

One of the prominent victims of the massacres was the martyred and posthumously canonized Greek Orthodox Metropolitan of Smyrna Chrysostomos [Kalafatis; 1867-1922], who had become a hate-figure for Turkish nationalists since 1914, when he invited European diplomats from Constantinople to inspect the atrocities committed in Ionia. Another motive specifically for Nureddin Pasha, the former military governor of the province of Smyrna until March 1919, was personal revenge: Chrysostomos had at that time persuaded the British to remove Nureddin. On 10 September 1922, Nureddin delivered the cleric to the lynch mob of about 1,500 men (see below Ureneck, Lou: The Death of Chrysostomos).

Although Chrysostomos had been offered a passage from Smyrna by the Catholic Archbishop of the city already on August 25, 1922, he declined the safe escape with the words: “It is the tradition of the Greek Church and the obligation of a priest to stay with his parish!” The American consul Horton described his death:

“The tales vary as to the manner of Chrysostom’s death, but the evidence is conclusive that he met his end at the hands of the Ottoman populace. A Turkish officer and two soldiers went to the offices of the cathedral and took him to Nureddin Pasha, the Turkish commander-in-chief, who is said to have adopted the medieval plan of turning him over to the fanatical mob to work its will upon him. There is not sufficient proof of the veracity of this statement, but it is certain that he was killed by the mob. He was spit upon, his beard torn out by the roots, beaten, stabbed to death and then dragged about the streets. His only sin was that he was a patriotic and eloquent Greek who believed in the expansion of his race and worked to that end. (…) He died a martyr and deserves the highest honours in the bestowal of the Greek Church and government. He merits the respect of all men and women to whom courage in the face of horrible death makes an appeal.”[19]

A few days before his death, on 31 August, Chrysostomos, as the Metropolitan of Smyrna sent a letter to Meletios, the Ecumenical Patriarch at Constantinople, in which he blamed the Allied High Commissionership for the destruction of the Ottoman Greeks because of its order to disarm them and in which he predicted the massacre of the undefended Christian population in Smyrna:

“(…) ‘Everybody feels that the greatest dangers and sufferings hang upon the unfortunate Christian population of the interior and of Smyrna,’ wrote the Archbishop, ‘because it is very well known that the Turkish populations, civic and agricultural, without any exception, are armed to the teeth, (…) because of the last three years’ negligence and good-will of the High Commissionership, and the other Greek military and police authorities.

A victorious entry of the Turkish Army in the cities of the interior, and most especially in the capital city of Smyrna, when to this army shall be added all the armed Turkish populations, which until now were living in full security under the cover of the Greek administration and the protection of the Greek Army, will be marked by excitements of rage and hate and by terrible slaughters. Needless to insist upon this point here, because we all have a very bitter and bloody experience of the continuous and inevitable slaughters and massacres which everywhere are marking the passage of Turks, whether they are victorious or defeated.

Unfortunately, the whole Greek population, that of the cities and of the villages, is armless, thanks to the very stern measures of the High Commissioner, who has not allowed even the Committee for the Defence of Asia Minor to buy and bear arms and to give arms to civil guards, which would greatly contribute to the rising of the morale of the Greeks for the protection of the lives of the citizens from the armed bands and the Turkish masses.

Thus, Greeks will be delivered to massacre and destruction. Hundreds of thousands of Greeks will perish without the possibility of the slightest defence, not even for its preservation for a few days and hours, until a European intervention may be affected to save the situation’.”[20]

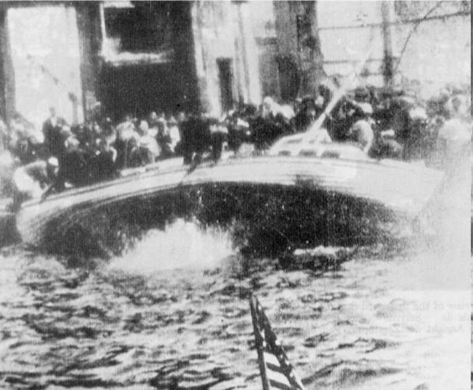

However, this intervention never happened. Numerous Christians drowned in the harbour of Smyrna, when trying to escape to the Allied navy of 27 battle ships, among them three American destroyers. It added to the horrors of the people of Smyrna that the Allies watched, more or less indifferently, how their Christian co-religionists were burnt, slaughtered, raped, shot down by machine guns or drowned:

“(…) What happened on the night of 31 August, on the waterfront of Smyrna, towards which the crowds of the Smyrniots were heading, continuously trapped by the fiery torrents of the burning city and the crowds of Nureddin, is related by the French historian Driault:

’Thousands of unfortunate people crowding along the waterfront fell into the sea. A great part of the port has been filled with hundreds of corpses that one could walk on them. Those floating on water were finished off by the Turks with swords and woods [clubs]…’ And the same writer adds: ‘Who will describe the atrocious scenes? … Countless lives, mostly women, children and old people have been massacred amidst ignominious savagery…’

The most terrible of all is that this orgy of blood, disaster and various other crimes took place under the eyes, frequently the spiteful smiles and even the cheers of the crews of the foreign war ships, or the official representatives of the Christian powers.[…]

The same (French) consul himself invited to dinner, (…) excused himself for his delay of a few minutes with these terrible words: ‘Because, he said, the motor-launch in which I was on my way from the French war ship hit continuously upon the floating corpses of Greek women’. And the American consul [George Horton] listening to this cynical excuse, spited himself for being a human being. […]

In the French Revue de Paris these terrible things are cited among others concerning the Christian population: ‘The cries of the massacred reached from the beach and the corpses of the drowned floated around the ships. Amidst this savagery sounds of music have been heard from a British war ship to the satisfaction of its passengers’. And the correspondent of The Times in Constantinople adds himself in his 3/16 September telegram: ‘A British party that was guarding the gas factory witnessed atrocious crimes at the expense of Greek women in the street without intervening, as they had the command to not intervene, except in an event concerning the security of the factory’.(…)”[21]

On 3/16 September 1922 Nureddin ordered a proclamation, according to which all Greek and Armenian men of 18 until 45 years of age would be treated as prisoners of war “until the termination of hostilities”.[22] All others, residents of Smyrna or refugees from out-side, were ordered to leave the country until 30 September 1922. Men and women were then separated, the men led away and shot in groups.[23]

Consul G. Horton wrote about the fate of the Greek-Orthodox men, deported from Smyrna and its vicinities after September 30, 1922:

“This last scene on the Smyrna quay reveals the whole diabolical and methodically carried-out plan of the Turks. The soldiers were allowed to glut their lust for blood and plunder and rape by falling first on the Armenians, butchering and burning them and making free with their women and girls. But the Greeks, for whom a deeper hatred existed, were reserved for a slower and more leisurely death. The few that have been coming back tell terrible tales. Some were shot down or killed off in squads. All were starved and thousands died of disease, fatigue and exposure. Authentic reports of American relief workers tell of small bands far inland that started out thousands strong.

The Turks allege that they carried off the male population of Smyrna and its hinterland to rebuild the villages destroyed by the Greek army on its retreat. This has a ring of justice and will appeal to any American unacquainted with the actual circumstances. The Greek peasants of Asia Minor were Ottoman subjects, in nowise responsible for the acts of the Hellenic government. Very few enlisted voluntarily in its armies and they used every influence and subterfuge imaginable to avoid fighting. Had the Greeks of Asia Minor been a stout warlike race and had they cooperated strongly with the Greeks of the mainland they could have kept the Turks at bay.

The object of Kemal, as we have seen, was one of simple extermination. The reason alleged was one of those shrewd subterfuges used by the Turks to fool Europeans. But not all the unfortunates carried away by the Turks were Greek men. Many thousands of Christian women and girls still remain in their hands to satisfy their lusts or to work as slaves. A report submitted to the League of Nations gives the number as ‘upward of fifty thousand,’ but this seems a very conservative estimate. The United States should sign no treaty with Turkey until these people are given up.”[24]

In 1923, the French author René Puaux pointed out to the distinct European dimension in the responsibility for the Smyrna disaster: “Perhaps the immensity of the tragedy of Smyrna could have been avoided or at least diminished, had there not existed a twofold illusion: the trust of the Great Powers in the Turks, and the trust of the Christians of Asia Minor in the Great Powers.”[25] Puaux estimated the number of Greeks deported into the interior of Anatolia as high as 150,000.[26] Most of these captives were massacred outside Smyrna or other Greek towns of Ionia/West Anatolia. The remainder was kept in a state of slavery[27] and treated with genocidal intent.

Many of the Greek survivors emigrated to Athens, where today the district of Nea Smyrni (Νέα Σμύρνη) still commemorates their origin. In the Treaty of Lausanne, İzmir and the entire west coast were granted to Turkey.

Lou Ureneck: The Death of Chrysostomos

“Chrysostomos and Noureddin [the military governor of Smyrna] were old antagonists: the bishop had successfully pressed the British for Noureddin’s removal in March 1919 ahead of the Greek landing, and Noureddin had not forgotten.

Late in the afternoon on Sunday, September 10, a French patrol called on Chrysostomos to offer him sanctuary at the French consulate. Chrysostomos declined, saying he wanted to remain with his flock, and as the French force was leaving the Greek church, a carriage with Turkish soldiers arrived and ordered him to climb in. He was told Noureddin wanted to see him, and he was taken to the general’s office at the Konak [seat of provincial government]. In their meeting, Noureddin reminded the bishop of an argument that had occurred between them in 1919 when Noureddin was the military governor. ‘On the last occasion that I had the pleasure of seeing you’, Noureddin said, ‘you were good enough to say that I ought be shot. I have sent for you, Lordship, to tell you that you are going to be hanged.’

Guards took Chrysostomos into the street where about fifteen hundred excited Turkish residents had gathered. Noureddin came to the balcony overlooking the street and, realizing that an alternative to hanging Chrysostomos had presented itself, said to the crowd that he was giving the bishop to them to do as they pleased. ‘If he has done good to you, do good to him. If he has done harm to you, do harm to him.’ The mob dragged Chrysostomos by his beard to a nearby barber-shop, where they wrapped him in a barber’s apron and beat and stabbed him. His eyes were gouged out and nose and ears cut off. The French patrol watched the scene, the men furious at what was happening, but under order not to intervene. Eventually, a bystander shot the bishop to end his misery.”

Excerpted from: Ureneck, Lou: Smyrna September 1922: The American Mission to Rescue Victims o the 20th Century’s First Genocide. New York: HarperCollins, 2016, p. 173

Rev. Charles Dobson: Sworn Testimony on an “excess of xenophobia”

“I was particularly struck with one group consisting of women and babies, and a young girl, almost nude, shot through the breast, and with clotted blood on her thighs and genital organs, that spoke only too clearly of her fate before her death. These bodies were buried by Orthodox priests. … There was desultory shooting, looting and rape all over the place. The Armenian quarters suffered severely. It was reported that the Armenians refused to surrender arms and were throwing bombs. This may have been so, but what is undoubtedly true is that the Armenians were constantly being killed in their houses, their women folks ravished and their valuables stolen. In the back streets even nationals of the Great Powers were held up and looted of their money and their valuables. Armenians, gathered in one of their churches, refused to surrender; they surrendered finally on the promise of life for women and children; the men were marched away. We heard at the back of our house, one day, a lot of cheering in which I recognized the Turkish word ‘padishah’ (Sultan, I think). On looking out, I saw about two hundred Greeks or Armenians kneeling and sitting on the road, guarded by Turkish soldiers. I afterwards learned from an absolutely unimpeachable source that these men were subsequently butchered. The method of killing, my informant told me, was by steel to avoid rifle fire. One could give a multitude of isolated incidents, which go to prove the absolute unleashing of lust and savagery among Kemalistic troops. I mention but one: A child brought a message to me from the priests of an Orthodox church, asking that I might come and spend the night with them in order to give them protection, because they had warning of a contemplated attack on the church and they knew that on the previous night Turkish soldiers had burst into another church and there mutilated men and violated women. The case of Colonel Murphy, a retired officer of the Anglo Indian Medical Service, illustrates the unbridled brutality of the Kemalist regulars. They broke into his house im Bournebat [today Bornova; previously also Burnabat, Bîrûnabad, or Prinobaris, Pyrinóbaris], they violated his servants, and when he attempted to protect them stunned him with household ornaments. His daughters escaped the fate of the servants by appealing to the officer of the party; he, evidently not able to control his men, could only advise them to hide. Colonel Murphy was stripped and insulted. Finally they stood him up and shot him. His wife, a lady of advanced years, was stunned; after being wounded for a considerable time, Colonel Murphy was rescued by Sir Harry Lamb personally, and brought to the English Nursing Home. His wife and daughters were obliged to leave him on the outbreak of the fire. He died at midnight and the hospital was evacuated at three in the morning under the protection of strong patrols sent by the Admiral. Hardly anywhere was there immunity for the Armenians. …

In the back streets there was, in some parts, a great running of terror-stricken people, carrying children and bedding; some of them had been injured; one man had his face smashed and his mouth bleeding. There was constantly shooting in the back streets, followed by screams and panic-stricken running. The Turks were openly looting everywhere. One man was shot through both thighs, one of which was fractured. The general atmosphere was terrible, and I began to fear that we might have left our retreat till too late. The fire broke out that afternoon. I was astonished when in Italy, and again here in France, to find how unwilling some circles were to believe the culpability of the Turkish troops in the burning of Smyrna. It seems to me that the firing of the city by the fanatic element of the Turkish Army was the natural culmination of the breakdown of restraint imposed by military necessities, and of the unbridled indulgence of xenophobia. I have not yet met anybody who was in a position to know the circumstances, who does not contemptuously discredit the assertion that the Armenians fired the city. During a month living in the Lazaretto of Malta as a refugee, I and my fellow refugees have compared experiences, and as a body when we heard of the statement that the Turks were not guilty of firing the city, asked the Bishop of Gibraltar who was visiting us to ask the people of England to suspend judgment until the truth could be known. The Bishop invited us to make a statement to him. We met him at the house of the Lieutenant-Governor. We were Herbert Epstein and the three British chaplains, respectively of Smyrna, Bournabat and Boudjat [Buca]. A report of our meeting will be found in the letter of the Right Reverend the Lord Bishop of Gibraltar in the Gibraltar Diocesan Gazette, No. 2, vol. VI, November 1922. It should be borne in mind that the considered opinion of these seven men, unanimously recorded here, is worthy of great respect. None of them was influenced by any consideration other than the upholding of the truth. And all had had exceptional opportunities of hearing the personal evidence of many people. This evidence, stripped of all hysteria, disproportion caused by personal loss, and human tendency to exaggerate, is such as to form a truly damning charge against the Turks, of having so far neglected the enforcing of discipline that their fanatic elements, in the excess of xenophobia, fed by the license of three days’ looting, fired the city in the hope of driving out the non-Moslem and non-Jewish elements. It is most significant that the fire shot up in several places with very little intervals of time and pointed to a systematic incendiarism such as only a well co-ordinated movement could have effected. Also, that the city was fired immediately after the changing of a wind that for the previous three days was in the general direction of the Turkish quarters. Independent witnesses, who have been at Smyrna since the fire, speaking of the unsatisfactory and lame stories of the Turks, tend to confirm their guilt in this matter. I have met, recently, a nurse, who left Smyrna ten days after the fire and who told me of her work in extracting bullets from bodies of wounded children, and who was a witness of the ravishing of Greek women. I mention this to show that the Turkish treatment of the Christian population was not a sudden excess, but a sustained policy. The Reverend Robert Ashe, now chaplain at Carthagena (Spain) told me of the fate the Greek priest of Boudja [Buca]; his informant was the brother of the Roumanian Consul. According to him, this priest was blinded and then crucified on the door of Mr. Gordon’s house in Boudjah [Buca] . The Turkish soldiers nailed horse shoes on his hands and feets; he was dead when the Consul’s brother saw him, he kissed his hands and left him there. (…)”

Excerpted from: Bierstadt, Edward Hale: The Great Betrayal: A Survey of the Near East Problem. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co., 1924; Reprint: Bloomingdale: The Pontian Greek Society of Chicago, 2008, pp. 224-227

Esther Clayson Pohl Lovejoy (Director, American Women’s Hospitals Service) : “The Smyrna Horror is Beyond the Conception of Imagination…”

After the start of World War I, the physician Dr. Esther Clayson Pohl Lovejoy helped establish the American Women’s Hospitals Service (AWHS) which was formed to bring humanitarian relief to displaced and injured victims of war. She was in Geneva attending a conference when the Smyrna fire broke out and was dispatched immediately by the American Women’s Hospitals. Esther Pohl Lovejoy was eye-witness to the fate of the approximately 200,000 remaining Christian women:

“I was the first American Red Cross woman in France, (…) but what I saw there during the Great War seems a love feast beside the horrors of Smyrna. When I arrived at Smyrna there was massed on the quays 250,000 people — wretched, suffering and screaming — with women beaten and with their clothes torn off them, families separated and everybody robbed.

Knowing their lives depended on escape before Sept. 30, the crowds remained packed along the water front — so massed that there was no room to lie down. The sanitary conditions were unspeakable.

Three-quarters of the crowd were women and children, and never have I seen so many women carry children. It seemed that every other woman was an expectant mother. The flight and the conditions brought on many premature births, and on the quay with scarcely room to lie down and without aid most of the children were born. In the five days I was there more than 200 such confinements occurred.

Even more heartrending were the cries of children who had lost their mothers or mothers who had lost their children. They were herded along through the great guarded enclosure, and there was no turning back for lost ones. Mothers in the strength of madness climbed the steel fences fifteen feet high and in the face of blows from the butts of guns sought the children, who ran about screaming like animals.

The condition in which these people reached the ships causes one to wonder if escape were better than Turkish deportation. Never has there been such systematic robbery. The Turkish soldiers searched and robbed every refugee. Even clothing and shoes of any value were stripped from their bodies.

To rob the men another method was used; men of military age were permitted to pass through all the barriers till the last by giving bribes. At the last barrier they were turned back to be deported. The robbery was not only committed by soldiers, but also by officers. I witnessed two flagrant cases committed by officers who would be classed as gentlemen.

On Sept. 28 the Turks drove the crowds from the quays, where the searchlights of the allied warships played on them, into the side streets. All that night the screams of women and girls were heard, and it was declared next day that many were taken for slaves.

The Smyrna horror is beyond the conception of the imagination and the power of words. It is a crime for which the whole world is responsible in not having through the civilized ages built up some means to prevent such orders as that of the evacuation of a city and the means with which it was carried out. It is a crime for the world to stand by through a sense of neutrality and permit this outrage against 200,000 women.

Under the order to remain neutral I saw the launch of an American warship pick up two male refugees who were trying to swim to a merchant ship under the Turkish rifle fire and return them to the hands of the waiting Turk soldiers on the beach for what must have been certain death. And under orders to remain neutral I saw soldiers and officers of all nationalities stand by while Turk soldiers beat with their rifles women trying to reach children who were crying just beyond the fence.”[28]