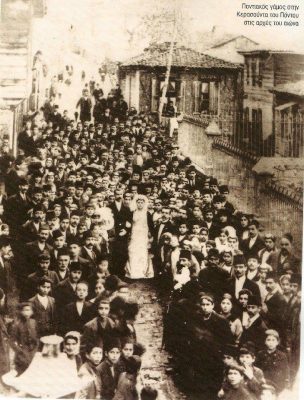

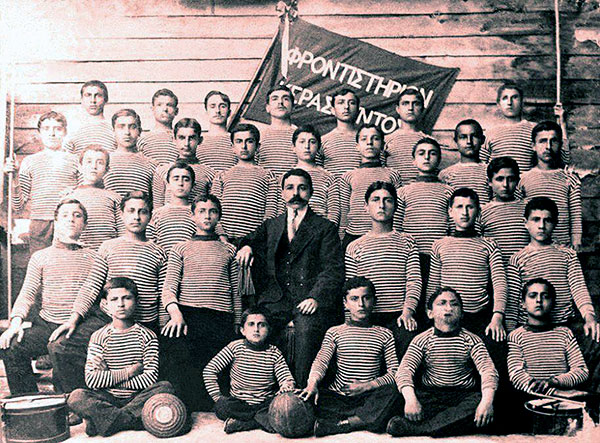

Toponym

Giresun was known to the ancient Greeks as Choerades or more prominently as Kerasous (Κερασοῦς). The place name Kerasounta (also: Kerasunda, Kerasun; Trk.: Giresun) is usually derived from the Greek κερασός (kerasós + -ουντ (a place marker). The English cherry, French cerise, Spanish cereza, Persian گیلاس (gilas) and Turkish kiraz, among countless others, all come from Ancient Greek κερασός ‘cherry tree’. According to Pliny, the cherry was first exported from Kerasous to Europe by the Roman commander Lucullus.

Another explanation relates to Greek ‘keras’ (κέρας) for ‘horn’. The Greek toponym Kerasous was Turkified into Giresun after Turks gained permanent control of the region in the late 15th century.

History

Since there have been few excavations in the region so far, not much is known about the history. It is assumed that the town of Aripša, which belonged to Azzi (Arm.: Hayasa) and was conquered by the Hittite Great King Muršili II around 1312 B.C., was located here. Early findings prove that Kerasous was inhabited by Greeks from the 7th century B.C., and thus ancient sources confirm that it was founded by Milesians.

In 183 B.C. Kerasous was renamed Pharnacia in honor of Pharnaces, the King of Pontos who took and destroyed Kerasous after capturing Sinope. It fell to Pompey in 64 B.C., but was not incorporated in the Roman Empire until a century later. The city struck its own coins.

In the Middle Ages Pharnakeia belonged to the Byzantine province Armeniakon. At the turn of the 7th and 8th centuries, there was an imperial office of commerce in Kerasounta which was associated with Trebizond and Lazika (Lazistan).

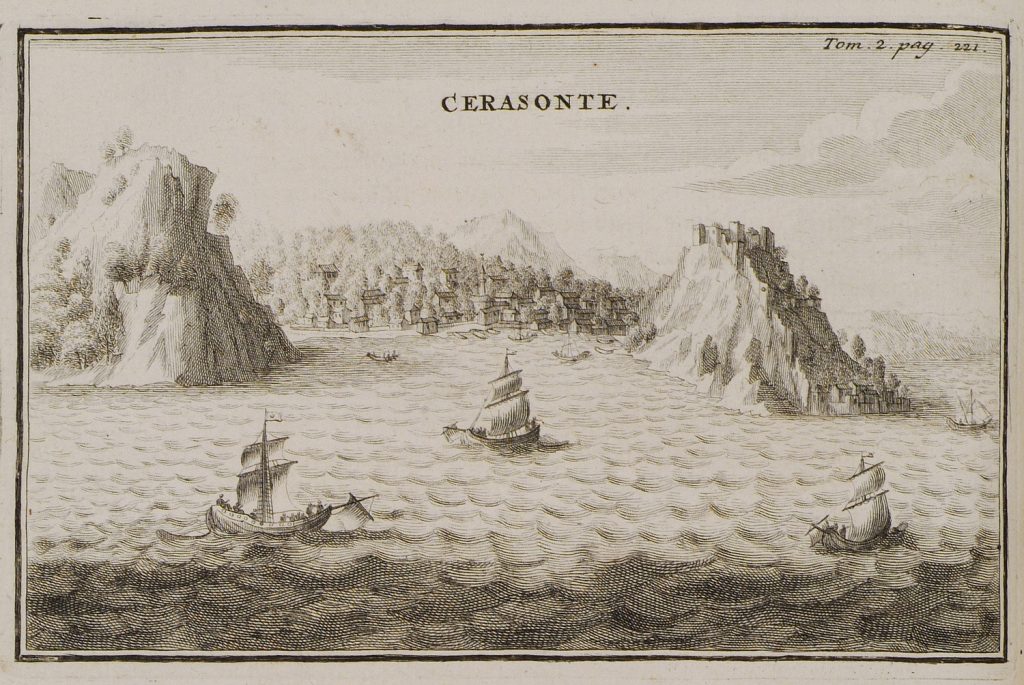

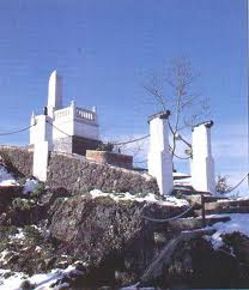

The victory of Alexios II over the Turkmen ‘Koustoganes’ at Kerasous in September 1301 was vitally important. If Kerasous had fallen in 1301, the Turkmen would have obtained major access to the sea and the days of the Empire of Trebizond would have been numbered. After 1301, Alexios II built a fortress which overlooks the sea.

Situated 4.2 km east-northeast of Giresun is a fortified island called Ares (Αρητιας νήσος or Αρεώνησος), today Giresun Adasi (island). According to Apollonius of Rhodes it was here that the Argonauts encountered both the Amazons and a flock of vicious birds. The Greeks of the island held out against the Ottomans for 7 years after the fall of Trebizond in 1461. With the start of Ottoman rule, many Greeks fled to nearby Russia or to the mountainous interior of Asia Minor.[1]

Economy

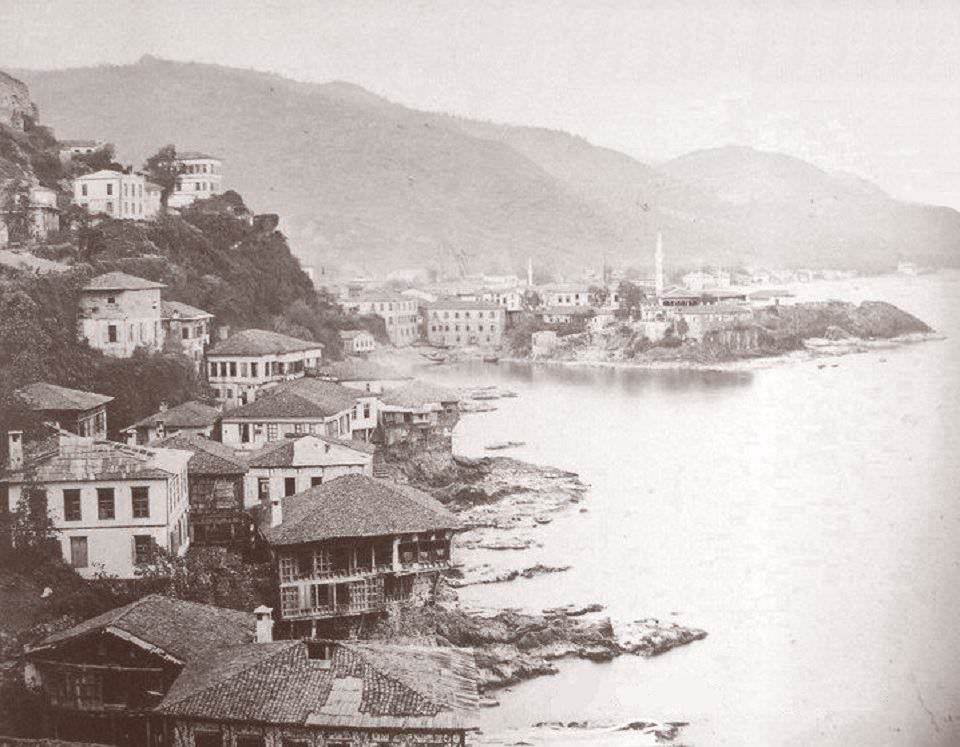

To this day the cultivation of hazelnuts is the most important agricultural product in the Giresun region. The city of Kerasounta (Giresun) was and is a major Pontic center of a highly important hazelnut trade. The surrounding area is rich in agriculture and grows also walnuts, apples and cherries. The port of Giresun has long transported this agriculture as well as products like leather and timber.

Further Reading:

Persecution

In 1764 during the Derebey Wars between two local Muslim feudal lords (‘derebeys’), the Greek population was completely devastated with the loss of almost all its churches, the ransacking of houses and shops, and imprisonment of many citizens.

In 1915 the Armenians were rounded up and massacred, while in 1919 Kemalist forces turned their attention to the Greeks and assigned Topal Osman the task of persecuting the Greeks of the region.

Population

In 1913, Kerasounta had a population of 30,000 which comprised 17,000 Greek Orthodox Christians, 3,000 Armenians, 7,000 Turks and 3,000 others.[2] “As in many other Black Sea ports, the Armenian colony of Kirason [Trk.: Giresun] developed after 1850 with the arrival of Armenians from Tamzara and Şabinkarahisar [Şebinkarahisar]. The Armenians numbered 2,075 on the eve of the First World War, plus 40 families in a peripheral village, Bulancak, where they worked in trade, hazelnut and cherry production, and anchovy fishing.” [3] The Armenian community of Giresun and Bulancak maintained three churches.[4]

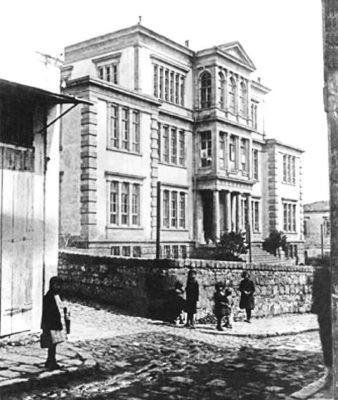

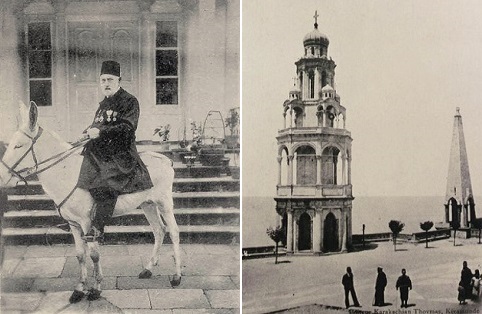

The most notable Greek of Giresun was Georgos (Giorgios) Konstantinidis (1828-1906), better known as Captain Yorghi Pasha. He was a ship owner, businessman and the Mayor of Kerasounta from 1889 till 1906. His family originated from the village Hopsa in the region of Gümüşhane. His father Constantine was also a ship captain while his grandfather was a metallurgist.

As Mayor of Giresun, Yorghi Pasha was responsible for improving the city in many ways including the construction of public gardens, roads, hospitals, churches, mosques, schools for Greeks and Armenians, and religious schools for Muslims.

His funeral was attended by many people including city officialdom, the kaymakam, the Greek-Orthodox Metropolitan, students from Greek, Armenian and Turkish schools. In all public offices a week’s mourning was declared. Yorghi Pasha was entombed at a height of 15 meters in the yard of the Church of Metamorphosis tou Sotiros. Following the 1923 exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, his tomb was desecrated by Turks.[5]

List of Greek Settlements in the Area of Kerasounta: https://pontosworld.com/index.php/pontus/settlements/157-kerasounta

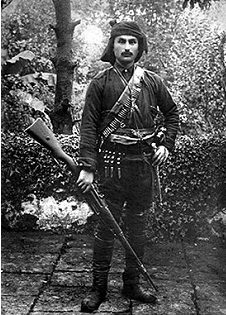

“Sadistic Ethnic Cleanser”: Feridunzade Osman Ağa alias ‘Topal’ Osman (Topal Osman Ağa; 1883, Giresun – 2. April 1923, Ankara)

Osman Ağa Feridunzade (Trk.: Feridunoğlu) was born in 1883 as the son of a merchant in Giresun and was probably of Circassian origin. His nickname Topal (‘the lame’) was gained after he was injured on his foot as a volunteer in the Balkan war.

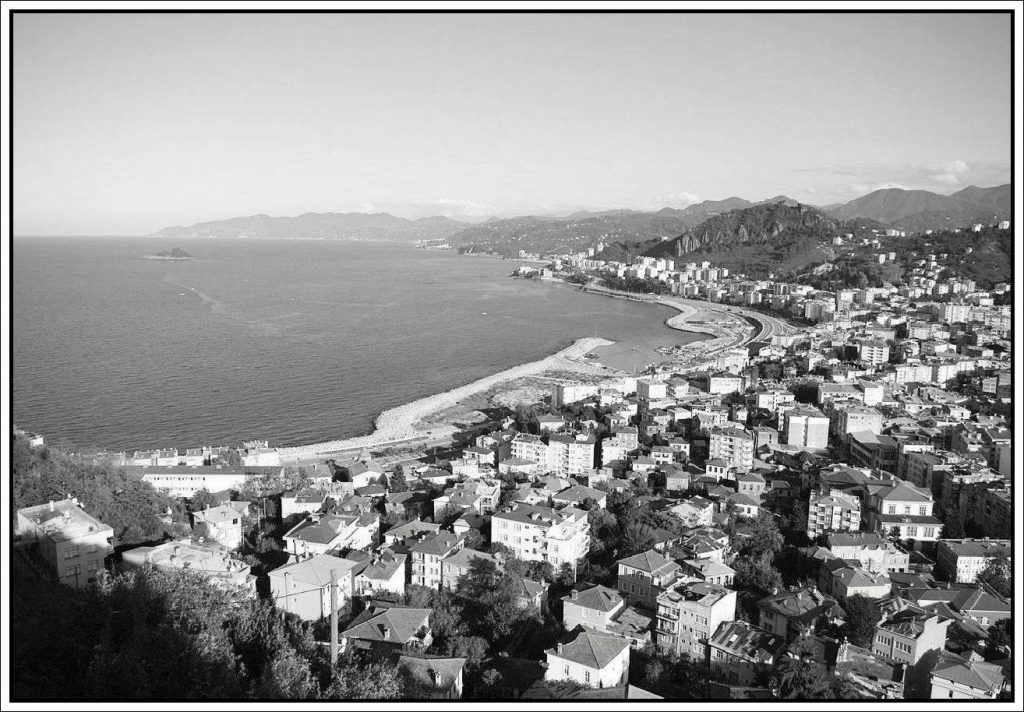

As commander of irregular Nationalist units in the Black Sea region since spring 1915 and as self-appointed mayor in his native city of Giresun (1918), Topal Osman was one of the main perpetrators of the genocide against the Pontos Greeks (1916-1922) and, since spring 1915, of the extermination of the Armenians in the Pontos region during World War I. The victims of Osman and his irregulars in both Pontos and the interior as far as the region of Balıkesir are estimated at about 70,000.(6) As mayor of Giresun, Osman Feridunzade decided to change the lay-out of the city. He had all the Christian-owned buildings that interfered with his plan blown up and forced the Greeks to carry away the rubble.(7)

He participated in the massacres of Armenians as an inductee of the ‘Special Organization’ (Teşkilat-i Mahsusa) of the Committee for Union and Progress (‘Young Turks’). In 1919 he was pursued for his participation in the massacres of Armenians and went underground for a while. With his associates, he began to organize the local resistance movement and later got in touch with Mustafa Kemal. He participated in the Erzurum Congress of the Kemalist nationalists. In 1920 he founded and headed a voluntary battalion from Giresun that served as the armed guard of Mustafa Kemal in Ankara until 1923. He also initiated the creation of the other voluntary battalions. Osman was appointed as a battalion commander in the repression of the Kurdish Koçgiri rebellion. He commanded the 42nd and 47th Giresun Volunteer Regiments; most of the approximately 3,000 cutthroats under his command were of Laz ethnicity. Osman then served as a commander in the Sakarya battle.[8] His last rank was Lieutenant-colonel of militia (Milis Yarbayı).

Osman along with his gang of cut throats, were responsible for massacres, deportations, destruction and confiscation of property, extortion, rapes and other atrocities throughout this region including the cities, towns and villages of Samsun, Marsovan, Giresun, Tirebolu, Ünye, Havza and Bulancak. He was however refused arms and cooperation by the government and inhabitants of Trebizond, where multicultural pro-Ottoman ideals were stronger than Nationalist affiliations due to inter-ethnic and religious family ties. Out of anger for this refusal, Topal Osman sacked some houses in a Christian neighborhood before being forced out of the city by armed Turkish port workers and officials.

Together with his subsequent murder of the Trebizond deputy Ali Şükrü Bey (leader of the first Turkish opposition party) this led to long standing animosity between the nationalist government of Mustafa Kemal and the population of the city of Trebizond. Osman choked MP Ali Şükrü Bey to death on 27 March 1923, allegedly in response to Şükrü’s criticism of Mustafa Kemal.

After the crime, regular military tried to arrest Osman. He was surrounded at his hideout in Seyran Bağları wards, and in the resulting exchange of fire, was wounded and captured on 1 April 1923. Later that day, under İsmail Hakkı’s orders, he was executed by a shot to the head. On 2 April, at the insistence of the ‘Second Group’, his body was dug up and hung at the gate of the parliament building (today War of Independence Museum) for exhibition to the public. According to some sources, his decapitated corpse was hung in the Ulus Square.

Turkish nationalists revere Osman Ağa as a national hero. However, his cult is more recent and goes back mainly to Kenan Evren and the year 1983. A statue of Osman was erected in his home town of Giresun in 2007. The erection of the statue has been linked to retired General Veli Küçük. Küçük’s first attempt to erect the statue was in 1981, but it was blocked by the Turkish Historical Society. Küçük tried again in 2001 but failed in his attempt after strong opposition from Mayor Mehmet Işık. It was finally erected in 2007 with the assistance of Ali Kara, chairman of the local small businessmen group of Giresun.

The Turkish historian and genocide researcher Taner Akçam, on the other hand, described Osman in 2001 as a “butcher of Armenians and Pontos Greeks” (Trk.: Ermeni ve Pontos Rumları Kasabı) in the Black Sea region. According to Mustafa Kemal’s British biographer Andrew Mango, Topal Osman was a “sadistic ethnic cleanser of Armenians and Greeks”. The Greek historian Konstantinos Fotiadis summarized his crimes in the following way: “Enjoying the support of Mustafa Kemal, Osman Feridunzade could impose his own law on the Kerasus (Giresun) area. The fact that he had escaped arrest by both the Sultan and the Allies—although he had been indicted for atrocious crimes against Christians during the war—coupled with his protected status under Kemal, increased his mythical status, while his anti-Greek prejudices led him to commit ever more extreme actions. He was not only the instigator of crimes, he was also the cold-blooded executor of many. A number of eminent Greeks were murdered by Osman’s own hand, among them the landowner and businessman, Charalambos Seitanidis; the lawyers, Panayotis Ermidis, Gregorios Moumtzidis, and Charalambos Eleftheriadis; the Director of the Greek Orphanage, Georgios Kalogeropoulos; Michail Mavridis, Ioannis Nasufis, Georgios Konstantinidis; the doctor, Thomaidis; and the city elder, Aristidis Delikaris.”(9)

Mortin Blancke: The Lame Mayor of Kerasund (1918)

The American Mortin Blancke, an employee of the Relief Committee in the Near East, got to know Osman Feridunzade during her stay in Giresun in 1918. In her article “The Lame Mayor of Kerasund” she reveals many aspects of his private and public life through 1918, although she was not aware of his guise as a dictator during Kemal’s ‘glorious’ period:

“The day I arrived [in Giresun] I heard about the Turkish mayor. Indeed, from that moment on I heard about nothing but him. In the Armenian orphanage his name was voiced with terror, while the Greeks discussed him with hatred. Foreigners saw him as a ridiculous figure, but this feeling was also couched in respect and fear. There was no question of his importance, although his office held little authority. The position of mayor came with no real power, since the real authority belonged to the administrator. Four administrators had come and gone in four months, leaving the field open for the man who had ejected them. The vali of Trebizond decided to turn a blind eye to the usurper, which is why he did not send any more administrators to Giresun. After the Armenian slaughter, his authority became dictatorial. His movements reminded one of the ancient chieftains who only needed to move their finger to exercise discipline. He was a nationalist and would happily sweep away every non-Muslim with a nod of the head. He was contemptuous of all European governments, which was strange, considering the relations Turkey has with them. In a small weekly newspaper there were a number of articles, supposedly written by Osman Ağa, which promoted his ideas. He believed that Europe had been in a state of barbarism for many years, and whatever culture it might have was due to its contact with Islam….(…)

I had stayed a long time with the Greeks. After my departure from Kerasund, I learnt that the Turks had lost Smyrna and other cities. We knew what the Turks response was, and about the war that broke out despite the Treaty of Sèvres. The first to react was Osman, who had become very powerful and was prepared to punish the Greeks in Asia Minor and the actions of the Greeks in Europe.

His first action was to arrest the village elders. It was impossible for the Greeks and British in Istanbul to combat his methods, which was to kill the Greeks, to burn down the town, and to go into the hills in case some foreign force tried to punish him. There is not even a handful of Greeks left in the area today. They have all been drafted into the Greek army and have been relocated elsewhere. It does no good to raise one’s arms at the horrors of the Turk.

Much of this barbarity is due to the imperialistic countries of Britain, France, Greece, and to America’s indifference.”

Source: Blancke, Mortin: “The Lame Mayor of Kerasund”, “Asia: The American Magazine of the Orient”Vol. XXII, Number 4 (April 1922); here quoted from: Fotiadis, Konstantinos Emm.: The Genocide of the Pontian Greeks. Monee, Ill., 2019, p. 331-333

Destruction

Escape and Emigration

Massacres in 1895 and 1896 caused mass flight and emigration among the Armenians of the capital Constantinople, including to Giresun: “In the weeks after the massacre, the authorities rounded up and imprisoned hundreds of Constantinople Armenians. Thousands in the city and its outskirts holed up in churches, which afforded relative safety. Thousands more were exiled to distant parts of the empire; about three thousand reached Trebizond, Giresun, and Samsun by boat. (…) The massacre also triggered a nationwide wave of Armenian emigration. On September 11 Shipley, the British consul in Trabzon, reported that some 1,400 Armenians, mostly ‘small traders, silversmiths, and artisans,’ had boarded steamships bound for Russia.”[10]

Also after World War I, intensive migratory movements in the region or emigration from Giresun were observed: British Lieutenant S.J. Perring, who was stationed on the Black Sea Coast, reported, “I found everywhere that Greek refugees who had returned to Turkey since the armistice have either left the country again or are on the point of doing so, in many cases accompanied by Greeks who had remained in Turkey throughout the war.” Armenians were leaving for Russia. In one village near Giresun, a party of Greek returnees was “met by the Turkish occupiers of their homes, beaten, and robbed . . . and forced to return to Kerasun.” The local Turkish authorities did nothing. But when Turkish villagers complained of Christian attack, gendarmes were promptly dispatched. “In many cases” they went on to pillage the Christians. In Platina, outside Trabzon, “the only Armenians to return . . . were assassinated shortly after their arrival.”[11]

Anti-Greek Boycotts

During the first months of the anti-Greek boycotts in the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople and Kerasunta (Giresun) were only places in which neither persecution nor boycotts were observed.

The stance of the local authorities played a decisive role in maintaining peace and order, as the Hellenic consul reported from Giresun: “In general, the atmosphere in our city and its surroundings is peaceful. The Turks have frequent commercial transactions with our people and many financial obligations towards them, both in the city and in the nearby villages.”[12] In the same document, however, the consul informed the ministry about the secret circulation of sealed letters, which was obviously a matter of concern, as well as about the issue of settling Muslim refugees:

“Here, as in other places, sealed envelopes have been distributed bearing the seal of the military authorities. The content is unknown, as the penalty for breaking the seal without authorization is severe. They could have something to do with an army draft.

Refugees: none were sent here. It is said that, at the inquiry in Istanbul, the kaymakam of our city replied that the quality of land in our region is not suitable to sustain refugees, and that is why none were sent here.”[13]

After June 1914 the Russian vice-consul of Kerasunta, Collaros, reported that signs of the boycott became manifest in the area under his surveillance: Giresun, Kotyora (Ordu) und Tripolis (Tirebolu).[14] The Austrian consul in Trebizond reported to the Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: “(…) In Kerasus, a directive was issued to Muslims through posters not to go to Greek barbers, because the Greeks had proved themselves to be infidel during the last war.”[15]

June 1915: The Deportations of the Armenians

“The procedure to eliminate the Armenian population here was classic. In the second half of June 1915, the police searched Armenian houses in Kirason [Trk. Giresun], officially looking for arms and deserters. Males between 16 and 50 were arrested and confined in the courtyard of the town hall. One hundred fifty to 160 notables were murdered the next night outside the city; the other men were set free. Only after these operations had been completed wass the deportation order made public.

The caravan in which our main witness found herself – the fourth and last – was guarded by gendarmes under the orders of Hasan Sabri. It comprised 1,200 people, 500 of them males. The males were separated from the others near Iki Su, halfway to Şebinkarahisar, and massacred by 82 ‘gendarmes’ near Eyriboli. The convoy then took the road to Tamzara and was pillaged in a Kurdish village in the environs of Şebinkarahisar, where girls and women were also abducted. In Kavalık, near Ezbider, the convoy was attacked by çetes [brigands, irregulars] from Kirason, who were led by Sari Mahmudzade Eşref and his brother Hasan, Katib Ahmed, the commander of the gendarmerie Kemal Bey, Major FAik, and an officer named Osman. They burned the last eight men in the convoy alive. After a 28-day trek, when our witness reached Kuruçay, between Şebinkarahisar and Divrig, there were only 500 deportees left in the caravan; they were natives of Kirason and the kazas of Tireboli and Görele. According to Mariam Kokmazian, they were attacked again, on the kaymakam’s Order, by Kurdish villagers; the 40 survivors of the caravan then set out for Demir Mağara, located somewhat south of Divrig, a place that had been given the name ‘Slaughterhouse of the Armenians’ by the local population because several thousand Armenians had had their throats cut there. On the 36 day these survivors reached Agn [Akn]/Eğin. Our witness was placed in the city’s Turkish orphanage, where 500 Armenian children were living in appalling conditions. When, somewhat later, these children were poisoned and thrown into the Euphrates, Mariam succeeded in escaping. At first she survived by working for a tailor in the city and later made her way to Sivas dressed as a Turk before moving to Konya and, finally, Istanbul.”

Quoted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 485 f.

1918-1922: The terror regime of Topal Osman Feridunzade

British lieutenant S.J. Perring wrote that Osman Feridunzade controlled the entire area and gave orders to the governor and other officers. In the villages, in particular, Osman and his followers ruled as tyrants. He was so overtly anti-Christian that he was determined not to allow any Greek or Armenian to re-settle in the hinterland. The vali of Trebizond accepted his inability to control the situation with the forces at his disposal (even if he wanted to do anything about Osman). Perring noted:

“The Greeks were expelled to the Sivas area, losing a large part of their community. They were ordered to return to their homes, but were once again denied this and were driven from one place to the next over the duration of the war.

The Armenian community has virtually disappeared and the few who are still alive took the first opportunity to abandon the country.

The Laz are very active and roam about freely, heavily armed.

There is no likelihood of any security returning to the area without military intervention. The Turks are not only anti-Christian but also openly antagonistic towards any interference. They declare with the utmost seriousness that if the Entente plans to get involved, they will resort to violence.

Mehmet Nuri, harbour chief and Turkish naval officer, was not only very aggressive, but he also informed me that if I wished to take prisoners from the local prison, I would have to use violence since he would put up resistance. This he made very clear.

All the Turkish community lives off the booty from the bandits as well as from the sale of the Christians’ belongings stolen during the evictions. It is evident that nothing will be returned unless violence is used.”[16]

According to Turkish scholar Murat Yüksel:

“No one heard the appeals and complaints of the unfortunate residents of Giresun. No one paid any attention to their accusations. The files in the law courts were full of writs against Topal Osman. However, a mysterious force was helping Osman, and, with every murder and accusation, he rose higher up the hierarchy. He was the most senior officer in Giresun, he was everything. All the strings were being pulled by him. He gave orders, proscribed, hanged. No-one could argue with him.

Even soldiers and public servants were beaten almost to death by him. Nothing would satisfy Topal Osman, he had to demonstrate his strength, cruelty and crudeness.

He was scared neither of the law nor of the government. Once this damned person had satiated himself with the countless murders of innocent people, he turned to political assassinations.[17]

After the deportation of the Greeks in the Kerasus region, it was the turn of Poulantzaki. This area is called Little Greece because of its totally Greek population, but in just two days, its entire population had been expelled.[18]

Confiscation of Greek Properties

“In the space of five years, Topal Osman had managed to strip the Greeks of Kerasun of their real estate, by raising unofficial taxes in addition to the regular Müdâfaa-i Milliye (National Defence) taxes and other ‘unconventional’ methods to provide for the 1,500 irregulars he maintained. Many families even sold their household furniture to survive. Christian women, young and old, were forced to leave their homes and sell whatever they had left of their household furniture and even their clothes on the streets. For this they received a measly cornbread.

With the encouragement of his advisers, Osman introduced a purchasing system for Christians’ belongings and houses. He would invite any Christian to the Property Office and in the presence of two Turkish (or unwilling Christian) witnesses to declare that, as owner of the property, he had supposedly received a certain sum in exchange for it. Thus, the property would be transferred into Osman’s name or that of one of friends. Subsequently, all the Greek property in Kerasun, worth millions of liras, passed into the hands of Osman and his associates.” [19]

Forced Labor and Eliticide

The Pontian Greek genocide survivor and eye-witness Georgios Valavanis recalled: “When the city’s work battalion, which consisted of the most prominent members of the local society, had finished their construction and transport work, Osman Ağa came up with the idea of deporting a certain number of them to unknown destinations. Some days later, the bodies of the chosen would be found in the outskirts of the city, atrociously mutilated. Even the pretenses of legality were soon completely abandoned. Those condemned to death were now called out by name and handed over to the executioners in broad daylight. The children of the doomed flocked to the prisons to embrace their fathers and brothers being taken to slaughter. (…)

Despite their proven innocence, several were imprisoned because they had lived abroad for many years (such was the case of Mr. A. Mavridis and Mr. G. Kakoulidis). Then, after having suffered indescribable torment, they were referred to the Courts of Independence. The priests suffered a stroke; their heads were cut off and put on display for everyone to see. Not one Greek or Armenian doctor was left in Kerasus. Of the previous physicals of the city, the unforgettable C. Papadopoulos, N. Saoulidis and P. Stefanidis perished during the war, judged guilty due to their profession. The Armenian doctors and the late Dr. Thomaidis were slaughtered. Only Dr. K. Deligiorgis and Dr. A. Malkotsis managed to escape certain slaughter, and are today living in free Greek territory.”[20]

“(…) the Turkish newspaper Peyâm-ı Sabah, which published a denouncement of the establishment of independence courts in the areas under Kemalist administration on December 29, 1921, wrote: ‘(…) and thus Anatolia was transformed into a slaughterhouse and became the battlefield for civil war. Countless families have been wiped out, and countless innocent people killed under the pretext of opposing Kemalist forces! At the same time, the country has been ravaged and suffered a regime of systematic seizure and plunder. Last summer [1920], Topal Osman Aga, whom Turkish newspapers commend and call a national hero, and 150 of his men went to Giresun, Amasya, Merzifon, Çorum and several other places, which they drowned in the blood of their victims. Osman continued on his way to Ankara in the same way’.”[21]

Mass Arrests and Massacres

“In Giresun itself, on the night of August 13, 1920, Osman imprisoned all the Christian men. Thereafter ‘every evening five or six Christians’ were taken out and shot, until the Christian community paid a ransom of 300,000 Turkish lira. While their husbands were in jail, ‘the women were violated.’ Greek men were deported inland from both Giresun and Samsun ‘at the order of Mustapha Kemal.’”[22]

“On August 30, 1920, (…) the Pontian population—ignored, unprotected and betrayed—was being sentenced to death. The Kerasun Committee in Istanbul revealed the final outcome of the tragedy of their fellow nationals to the Hellenic Prime Minister: ‘The predicted devastation of the Greeks of Kerasun is under way. Topal Osman Aga arrested the male population during cover of night, locked them, bound hand and foot in a school, a club, and at other locations. Gangs looted shops and homes, as well as ravaging and raping women and children. Of those incarcerated that night, certain individuals were picked out for slaughter. Women and children were decimated by terror and hunger. Greeks, in particular, were slaughtered in large numbers. If swift measures are not taken to save those incarcerated and to rescue the women and children, the extermination of the Greeks in the provinces of Kerasun through slaughter and hunger will be a fait accompli. We appeal to Mother Greece for pity and immediate help. Save our people from slaughter.’

On August 31, 1920, Topal Osman, on the pretext of the imminent occupation of Kerasun by the British fleet, had ordered the Turks in the town to withdraw while he himself arrested all the Christian men, whom he rounded up in a Greek school, the Belle Vue Hotel, and another large building, intent on murdering them all. Then ‘the women were raped and all the Christian houses were plundered by the tyrant’s hordes. Every evening, he would take five or six Christians from the school and kill them. Only when they had paid 300,000 pounds in ransom (in silver and in goods) were they set free. Fear ruled the town. Cases of madness because of terror occurred amongst the Christians’.”[23]

In the regional Pontos edition of Eleftheros Pontos (‘Free Pontos’, Batumi) of October 28, 1920, it is written that in Giresun “100 young Greeks were taken outside the city and slaughtered. The bravest among them, Georgios Valavanis, who dared to speak, had his tongue and arms cut and tossed into the sea. Two young men accused of approaching a Muslim woman, were chopped up. Osman’s son danced around the bodies”.[24]

“Soon after the massacre at Merzifon [July 9121], Osman and his brigands moved to the area of Tirebolu and Giresun, where, after killing many Greeks and deporting others, he took the most beautiful women for himself and his men. He was subsequently welcomed with great fanfare in Ankara and placed in command of 6,000 men. According to an American missionary, his portrait appeared on a Nationalist postage stamp.”[25]