Armenian Population

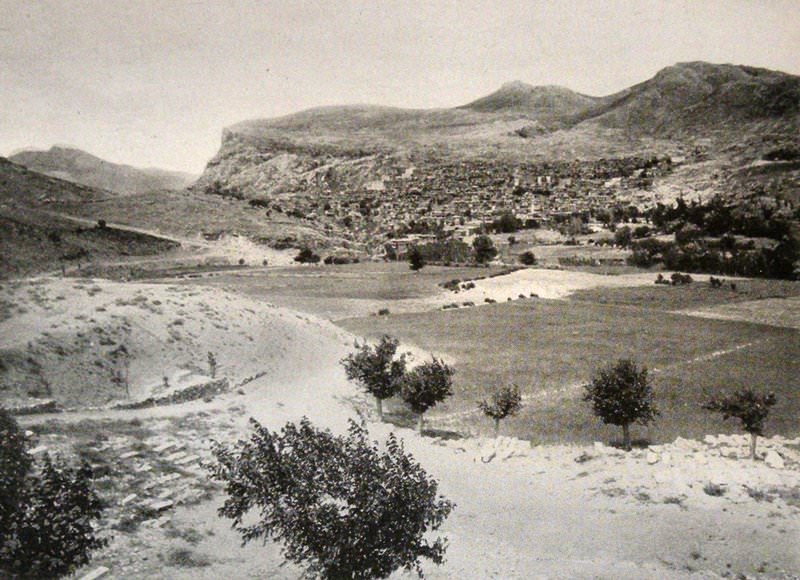

In the sparsely populated kaza 12,418 Armenians lived in three localities. Around 2,000 of them resided in the administrative seat, Chermuk (Arm.: Jermuk – Ջերմուկ, ‘Hot Springs’), and more then tenthousand in Chnkush (today Çüngüş), where they were settled “on an impressive rocky plateau that dominated the Euphrates valley.”[1] The Armenian communities of the kaza maintained five churches, one monastery and five schools with 500 students.[2]

Destruction

“In this remote region, the authorities’ strategy seemed to consist in liquidating the Armenians where they were found: there was not race of deportees from this kaza in the concentration camps of Syria and Mesopotamia.

Chnkush [Çüngüş] is the best-documented case, thanks to the five survivors whose accounts were recorded by Karnig Kévorkian. Conscription emptied the town of men between 18 and 45, including those who had paid the bedel to avoid the draft. The requisitions were the financial ruin of the tanners and fur traders (two of the town’s specialities) and left the muleteers without their animals (…). The anti-Armenian exactions began there as soon as the müdir, Karalambos, a Greek from Maden who had been in office since September 1906, was dismissed from his post by [governor] Reşid for refusing to organize police searches of the Armenians’ homes. Twelve cavalrymen were waiting for him one morning in front of his home, and he was forced to follow them. He was replaced by the more flexible Ferik Bey on 1 July (…). Systematic searches of the Armenians’ homes began soon thereafter. The Armenian prelate Yeghia Kazanjian, the Protestant minister Bedros Khachadurian, and Father Pascal Nakashian, a Catholic priest, were all arrested. The Protestant was the first to die, under torture in the ‘prison’ of Chnkush; the Apostolic clergyman was massacred along with his flock, and the Catholic priest was deported to Dyarbekir, where he was put to death somewhat later. The Armenian notables were also arrested. Among them were Abraham Kaloyan, Hagop Gulian, and Hovsep Der Garabedian, who were sent to the administrative seat of the sancak, Arğana Maden. Forty others were dispatched to Dyarbekir to stand trial before the court-martial. They were accused of being ‘revolutionaries.’

In July, the remaining men were methodically arrested. Then came the women and children’s turn. All were deported in several convoys to the chasm of Yudan Dere (which the Armenians call ‘Dudan’), two hours northeast of the town. They were joined on the way by deportees from neighboring areas, notably Arğana Maden. The rare survivors report that the convoys were escorted by Circassian gendarmes (…). It was these gendarmes who were also stationed on the promontory that towers over the chasm of Yudan Dere. The males were dealt with first, in accordance with the classic procedure: tied together in small groups of fewer than ten, they were handed over to butchers who bayoneted them or killed them with axes and then threw the bodies into the chasm. The method used on the women was quite similar, except that they were first systematically stripped and searched and then had their throats cut, after which their corpses were also thrown into the chasm. Some of them preferred to leap into the abyss themselves, dragging their children with them; thus they cheated their murderers of part of the booty.

According to Karnig Kévorkian, 13 people survived – a few men who had taken refuge in the mountains and a handful of young women who had been abducted to Yudan Dere.”[3]

Fethiye Çetin: My Grandmother (A Memoir)

One day, when I found my grandmother alone in the house again, I took her hands into mine, kissed her soft cheeks, and asked her to continue the story where she had left off. Without a moment’s pause, she began to speak:

The man who took me was Corporal Hüseyin, the commander of the Çermik gendarme headquarters. His wife’s name was Esma. Though they dearly wanted children, they’d not been able to have any. Hüseyin – bless his soul, and may Allah show him an abundance of mercy – was a good man. He had as much power as a major. He considered me his child and looked after me very well.

They used to call him a soft-hearted man. They had massacred the Armenians of Çermik, too, and thrown them into a bottomless well. There’s a waterwhole between Çermik and Çüngüş that they call Duden [Düden, also Dudan], and they say it has no bottom. After cutting off their heads, they threw the Armenians into this Duden. Colonel Hüseyin was there for the massacre of the men, but he refused to take part in it when they threw the women and children; he refused to obey orders. They said he’d been punished for this.’”

Excerpted from: Çetin, Fethiye: My Grandmother: A Memoir: London, New York: Verso, 2008, p. 67

Further Reading:

Bojahlian, Chris: In a Turkish town [Çüngüş] that had 10,000 Armenians, now there is only one. ‘Washington Post’, 6 June 2013; https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/in-a-turkish-town-that-had-10000-armenians-now-there-is-only-one/2013/06/06/d893197a-c93e-11e2-9f1a-1a7cdee20287_story.html?tid=a_inl_manual

“Yeniköy elementary school sits above the Dudan Crevasse, where an estimated 10,000 Armenians were killed in 1915. (Courtesy of George Aghjayan”; ‘The Washington Post’, 5 Sept 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/near-a-turkish-school-10000-dead-armenians-are-still-ignored/2014/09/05/f0b7baa2-346c-11e4-a723-fa3895a25d02_story.html)