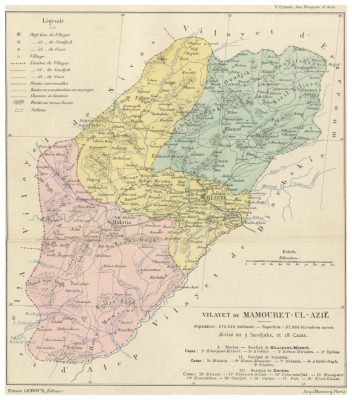

The Vilayet (Province) of Mamuret-ul-Aziz, also referred to as Harput Vilayet (Ottoman Turkish: ولايت معمورة العزيز; Vilâyet-i Ma’mûretül’aziz, Armenian: Խարբերդի վիլայեթ Kharberd) was located between Euphrates and Murat (Aradzan) river valleys. Near the administrative center of Harput (Kharberd; today Elazıg) is Lake Gölcük (auch: Göljuk; Armenian: Ծովք լիճ – Covk’ lič, also: Tsovk; today: Hazar Gölü), notable as the source of the Tigris.

Administration

In the 18th century, Kharberd (Խարբերդ; Trk: Harput) administratively belonged to the Sivas province. With the administrative division of the Ottoman Empire in 1834, Harput became a sancak of the Diyarbekir Eyâlet. In 1878/1879 this sancak was elevated to the status of a province (vilayet) that included the Malatya sancak. In 1888 by an imperial order Hozat Vilayet (Dersim) was joined to Mamuret ül-Aziz.

In the 1890s, the Ottoman Province of Mamuret ül-Aziz covered a territory of 37,800 square kilometer (32,900 in the early 20th century), consisting of the three sancaks of Harput-Mez(e)re, Dersim (Hozat) and Malatya, sub-divided into 18 kazas.

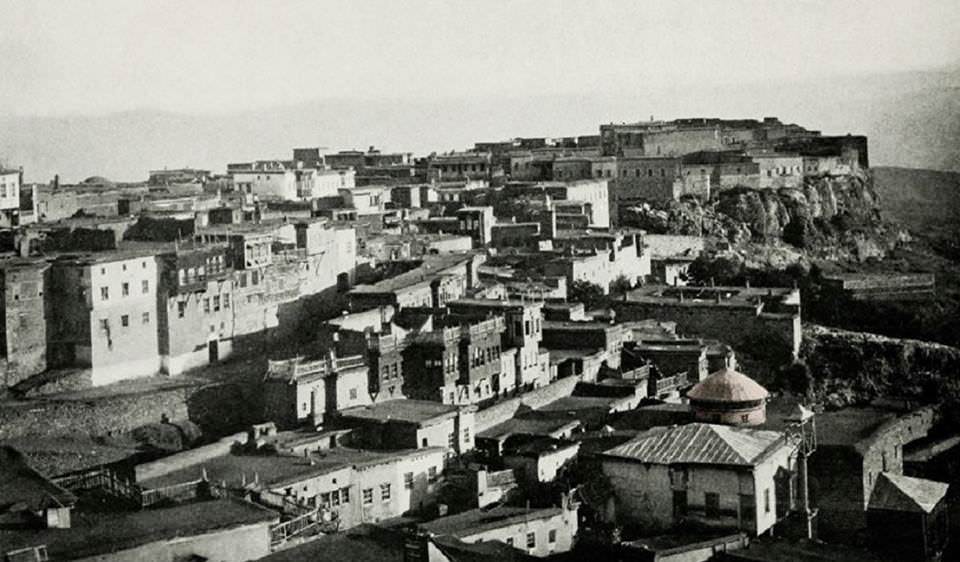

Because Harput city was well protected by its location but difficult to access, at the beginning of the 19th century the local governors moved their residence to the small village of Mezre, which was close by but located on the plain. The village developed rapidly and was officially proposed as the seat of the local administration as early as 1834. In the same year the governors of the sancak of Harput moved their residence to the town of Mezre (also Mezere, Mezereh), on the plain to the northeast, and some of Harput’s population moved with them. In 1838 a barracks was built in Mezre as a local base against Muhammad Ali of Egypt. Mezre (and in its wake the sancak) was named Mamuret ül-Aziz (‘The Town rendered prosperous by Aziz’, shortened Elazığ) in 1862 in honor of Sultan Abdülaziz. In 1879, Mezre was built up into a large city named Mamuret el-Aziz, which became modern Elazığ.

Toponym

The Turkish place-name Harput derives from Armenian Kharberd or Karberd, composed by ‘k’ar’ (‘stone’) and ‘berd’ (‘fortress’). According to another explanation, Kharberd derives from the Khar village, which existed for 2000 years, to which the suffix ‘fortress’ was later added.

According to a third explanation, Kharberd was a sanctuary dedicated to Khati, the Hittite goddess of hunting, farming, and the moon, from which it took its name. The ancient Greek geographer Strabon (Στράβων; 64 or 63 B.C. – c. A.D. 24) mentioned Karberd / Kharberd (Grk.: Καρκαθιόκερτα – Karkathiokerta) as the capital of the Sophene (Armenian: Dsop’k’) kingdom, but most scholars today identify Karkathiokerta, the ‘city of prophets’, with the modern-day town Eğil (near Diyarbakır).

In 1937, the name of the administrative seat Mamuret ül-Aziz was officially changed to Elazığ according to the popular pronunciation.

Population

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the population of the province as 575,314. Of this total, according to the French geographer Vital Cuinet 69,718 were Armenians, 650 Greeks and the rest were Turks, Kurds and Kizilbash. The accuracy of the Ottoman population figures ranges from “approximate” to “merely conjectural” depending on the region from which they were gathered.

“It will be noticed that (…) Cuinet has been more conservative than the Turks. The numbers given by Armenian sources for the Armenians in Elazığ are quite different (…). Theodik’s [Theodoros Lapchindjian, 1873-1929] almanac presents the approximate total of 204,000, while [Patriarch Malachia] Ormanian, (…) estimates it at about 131,200. (…) We are inclined to accept Ormanian’s statistics as, relatively speaking, more reliable.”[1]

According to Johannes Lepsius, the Vilayet Mamuret ül-Aziz counted 174,000 Christians among 575,300 inhabitants, namely 168,000 Armenians, 5,000 Syriacs and 1,000 Greeks. The Muslim population consisted of 180,000 Alevi Kizilbash, 95,000 Kurds (75,000 sedentary and 20,000 nomadic), 126,300 Turks. [2]

Based on the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, the French-Armenian scholar Raymond Kévorkian gives the following statistics and demographic peculiarities for the Armenians: “Located at the point of confluence of the two branches of the Euphrates, the region included on the eve of the First World War 270 towns and villages with a total Armenian population of 124,289. It boasted 242 churches, 65 monasteries, and 204 schools attended by 15,632 children. (…) the vilayet’s Protestant Armenian community was exceptionally big; its importance was due not just for its size but, first and foremost, to its members’ level of education. The cultural gap between the Armenian and Muslim – especially Kurdish – populations seems to have been widening in the years before the war, as were the socio-economic disparities between the two groups. The permanent ties between the region and its 26,917 emigrants, most of whom had settled in the United States, help explain the accelerated modernization of the Armenian society, or at least its urban segment.”(3)

Trades and Professions of Armenians

The Armenians of the province were engaged in cultivation of the fields and on the mountains, and in the towns, they were busy in various trades and professions. “In Harput many Armenians were occupied in the textile industry, dealing with imports and exports. The brothers Fabrikatorian and Kürkdjian and the son Khosrov had big concerns manufacturing silk textiles. Other renowned firms in textiles were the families of Shaghalian, Hambartzumian, Tevrizian, Enovchian, Tüfenkdjian, Hindlian, Darakdjian, Demirdjian, etc. According Ephrikian the handwork of the Armenian ladies, the works of fine goathair, and the beautifully woven rugs and carpets were appreciated very much.

The Armenians co-operated with the Ottoman Government in mining and iron work also. At Maden (Ergani Maden) the Ignatiosian family were engaged in copper mining, and at Keban the Arpiarian family worked the silver mines by Imperial writ. The iron factory of the Parikian Brothers in Harput was well known and even carried out work for the government.

In the other kazas also of the sancak of Elazığ the Armenians were the main industrial element. Almost all of the craftsmen of Arapgir [Arabkir] were Armenian, and in Kemaliye [Akn]‘the majority of the merchants, of the retailers, chemists and watch-makers were Armenian… but half of the carpenters and hair-dressers were Armenian, and the other half were Turkish.’

In the sancak of Malatya the Armenians were engaged in the preparation of dried fruits, in cotton textiles and various crafts and professions. (…)

In the province of Elazığ the popular professions of the Armenians were medicine and pharmacy.”[4]

History

The medieval area of Kharberd corresponds with the ancient Kingdom of Sophene (Armenian Dsop’k’) and later Armenian province of Sophene.

Western Mission and diplomatic representation in the ‘Slaughterhouse Province’

In the second half of the 19th century Harput attracted missionaries of Western churches: French Catholics, German and American protestants. The Rev. Herman Norton Barnum explained the reasons for this as follows:

“No city in Turkey is the center of so many Armenian villages, and the most of them are large. Nearly thirty can be counted from different parts of the city. This makes Harpoot a most favorable missionary center. Fifteen out-stations lie within ten miles of the city. The Arabkir field, on the west, was joined to Harpoot in 1865, and the following year…the larger part of the Diarbekir field on the south; so that now the limits of the Harpoot station embrace a district nearly one third as large as New England.”[5]

The United States established a consulate in Harput from 1 January 1901 with Dr. Thomas H. Norton as the consul; he had no previous experience in international relations, as the U.S. was just recently establishing its diplomatic network. The U.S. consulate in Harput remained the only U.S. diplomatic mission in Anatolia. It was established to assist the missionaries. The Ottoman Ministry of Internal Security gave him a tezkere travel permit, but the Ottoman Ministry of Foreign Affairs initially refused to recognize the consulate.

The building had three stories, a wall, and a garden with mulberry trees. Leslie A. Davis became consul of Harput in 1914 and left in 1917 upon the cessation of Ottoman Empire-United States relations, after the US entered the World War; Davis stated that this mission was “one of the most remote and inaccessible in the world”.

American missionaries and diplomats, as well as the head of the German mission station, became eyewitnesses to the extermination of Armenians in Mamuret ül-Aziz province.

Leslie Davis was among the mixed party of Americans who examined the mass graves of Armenians killed near Harput. Davis subsequently wrote a vivid account to the Department of State where he described the tens of thousands of Armenian corpses in and around Lake Gölcuk (present-day Lake Hazar), during his trips to the lake. In his account he paraphrased Harput as the ‘slaughterhouse province’; his report was published in 1989.[6]

L. Davis aided some Armenians by allowing some 80 of them to live in his consulate and organizing an underground railroad to get other Armenians to cross the Euphrates River and into Russia. He acted even though there were warnings by the Turkish government to not aid any Armenians.

Another American eyewitness was Dr. Henry H. Riggs, the Turkey-born congregational minister and ABCFM missionary who had been the head of Euphrates College, a local college founded and directed by American missionaries for mostly the Armenian community in the region. Riggs spoke both Turkish and Armenian. His report was documented and sent over to the United States, and then published under Days of Tragedy in Armenia (1997).

“The gradual confiscation of the buildings that housed the American institutions can be explained by the Young Turks’ desire to eliminate foreign influences from the country and, secondarily, by the army’s needs for barracks and office space. However, the takeover of the American schools, decreed on 26 March 1915, was no doubt also designed to eliminate any and all zones beyond the authorities’ control – that is, to leave the Armenians no way out. It is, moreover, telling, that the first step the vali [province governor] took was to arrest most of the Armenian faculty of these schools.”[7]

Destruction

The presence of foreign mission stations and a U.S. consulate explain the fact that there are exceptionally many and diverse sources about the extermination of the Armenian population in this province, especially about what happened in and around Harput-Mezre. From them, the following picture emerges:

A preparatory phase in April to the end of May 1915, with house searches, confiscations of weapons, arrests of notables, and growing pressure, was followed from 6 June 1915 by a phase of mass arrests in the towns of Harput and Mezre, which was extended to the villages in the Harput plain from 8 June. On 10 June, Mezre was surrounded by troops, all Armenian stores were closed and the leading citizens were arrested. By 18 June, over 4,000 Armenians were in Mezre prisons, either in solitary confinement in the central prison, or – in most cases – in the ‘Kırmızı Konak’ (‘Red Konak’) on the western outskirts of Mezre. Among those imprisoned were also 3,000 forced laborers and 500 artisans from Harput who had been in the service of the government and the army. Every night, about 50 men were taken to the prison’s torture chamber and returned only in the early hours of the morning, just before Mezre’s garbage collectors took over the bodies of those prisoners who had not survived the night.

On the morning of 18 June, 2,000 prisoners were herded in four groups toward Urfa and massacred en route by regular cavalry and infantry soldiers under the command of Çerkes Kazim, one of the commanders of the Special Organization militias. The very next morning, the prison was filled with men from the surrounding villages who had been arrested during the night. On 22 June 1915, about one thousand Armenian peasants and urban notables were in the Red Konak. Those nine hundred who had not been able to buy their way out were shot at the foot of Mt. Heroğli on 24 June. On the following two days, the remaining Armenians were arrested and some of them were murdered near Mezre. After that, the authorities apparently opted for more remote locations such as the Güğen Boğazi gorge near Maden. By the end of June 1915, further deportations of the imprisoned men from the center of the province of Mamuret ül-Aziz ‘to Urfa’ followed, and they were massacred in groups.

On 26 June 1915, the town crier announced in all Armenian households of Mezre that all Christians would be deported southward and that the first convoy would leave in five days. Although the deportation order also applied to Syriacs, according to Henry H. Riggs, it was revoked the same day; Syrian Catholics in particular were spared. A surviving Armenian eyewitness noted that Syriacs were, however, deprived of all their property and some of them were also killed. Armenian Protestants and Catholics were also initially exempted from the deportation order. However, this exemption was announced only after the Armenian Protestants and Catholics had already been deported. Interior Minister Talat furthermore called on the Kurdish-origin provincial governor Sabit Cemal Sağiroğlu to take the steps required to settle muhacirs (Muslim refugees) in the ‘evacuated’ Armenian villages-that is, to “make a clean sweep of things.”[8]

“The other regional particularity is the role of the pivot or hub of the deportation that fell to the vilayet Mamuret ül-Aziz in 1915, nearly all the convoys of deportees from the regions of Trebizond, Erzurum, Sivas, and the eastern part of the region of Ankara passed through the ‘slaughterhouse province’ and lost some of their members there. The concentration in the sancak of Malatya of a large number of killing fields to which certain squadrons of the Teşkilat-Mahsusa were permanently attached tells us something about the procedures the authorities adopted to eliminate the deportees, the çetes’ operational methods, and the routes taken by the convoys.”[9]

In 1915, the most serious atrocities against Armenian children took place in Mamuret ül-Aziz province. “According to the account of an eyewitness, in another instance in Furuncular, district cf Malatya, (…) the gendarmes buried alive in a large pit dug beforehand 90-100 Armenian children, aged 3-4. The victims, sensing their imminent death, started to scream hysterically and hopelessly as they were thrown into the pit, located in a place ironically named ‘The Garden of Children’ (Çocuklar bahçesi). But the gruesome operation was completed in just a few minutes.”(10) Also in the province of Mamuret ül-Aziz, the kaymakam Kadri “burned to death 800 children who were from Palu” in Diyarbekir province.(11)

Henry H. Riggs: “Our Position of Impotence” (June, 1915)

“Mrs. Smith and I started from Diarbekr with one thought uppermost in our minds. If we could only reach Harpoot, we would there be able to communicate to the outside world the horrible state of affairs in Diarbekr—with some hope that help might come to the agonized Armenians there as a result of our appeal. When we reached Harpoot, however, our hopes in this respect were suddenly dashed. We found the same conditions of terrorism and semi-anarchy in Harpoot that had so horrified us in Diarbekr. And in spite of the presence there of the American consul and of American and German missionaries, there seemed to be not possibility of securing relief for conditions that were evidently not local or due to the personal brutality of the officials in charge. Evidently, those officers, both in Diarbekir and in Harpoot, were carrying out orders that had a common origin.

(…) Men were brutally arrested right and left. Terrible rumors of massacres and violence were coming in from all sides. It was evident that the storm which had been raging in Diarbekr was also reaching Harpoot. The search for weapons among the Armenians was being prosecuted with the greatest vigor, and torture was being used to force the Armenians under arrest to reveal the whereabouts of the weapons. The Armenian population was being reduced to a state of terror that was pitiable to behold and which was evidently one of the purposes of the campaign that was being waged against them. At such a time as this we longed for our old-time freedom to interfere in some way in behalf of our afflicted people, but the capitulations had been abrogated, and the local officials took pains to make it clear that they would brook no interference on our part in their domestic troubles.”

Excerpted from: Riggs, Henry H.: Days of Tragedy in Armenia: Personal Experiences in Harpoot, 1915-1917. (Ann Arbor, Michigan: Gomidas Institute, 1997), p. 61f.