The Toponym

The Greek place name Melangeia (Malágina – ‘blackbird’) is documented for the year 1308, the Turkish name Yenişehir (‘New City’) dates back to 1484.(1)

History

Yenişehir is perhaps the oldest Ottoman city foundation. Its known history dates back to the early 14th century, when it was established by building permanent houses for the first time from the tent life in the Beylik period of the Ottoman Empire, and was used by the Ottoman Army in Anatolia and Middle East expeditions due to its wetland and wide plain. The city was founded by Osman Gazi, where for the first time, coins were printed, taxes were collected, a regular army was started to be established, and the first law (edict) was commanded here. For the short period of 29 years the city was the Ottoman capital (although Söğüt is also claimed to be the capital), until Yenişehir handed over the duty as capital with the acquisition of Bursa. After the capture of Köprühisar and Yarhisar in the founding stage of the Ottoman Empire, Osman Bey gave this region to his veterans as a sword right. Yenişehir became known with this name for the first time since it was opened for construction.

Yenişehir is perhaps the oldest Ottoman city foundation. Its known history dates back to the early 14th century, when it was established by building permanent houses for the first time from the tent life in the Beylik period of the Ottoman Empire, and was used by the Ottoman Army in Anatolia and Middle East expeditions due to its wetland and wide plain. The city was founded by Osman Gazi, where for the first time, coins were printed, taxes were collected, a regular army was started to be established, and the first law (edict) was commanded here. For the short period of 29 years the city was the Ottoman capital (although Söğüt is also claimed to be the capital), until Yenişehir handed over the duty as capital with the acquisition of Bursa. After the capture of Köprühisar and Yarhisar in the founding stage of the Ottoman Empire, Osman Bey gave this region to his veterans as a sword right. Yenişehir became known with this name for the first time since it was opened for construction.

Later, the town was connected to the Ertuğrul sancak, where Bilecik was the center at that time, and continued this position until 1926. The much older Iznik was a subdistrict of the city between 1926-1930.

Yenişehir was occupied by the Greeks during the Turkish War of Independence/Greco-Turkish War between October 27, 1920 and September 6, 1922. The establishment of the villages in the Yenişehir kaza goes back to Byzantine times, for example, the Yarhisar neighborhood is known to have Tekfur barracks during the Byzantine period. Likewise, Akbıyık and Süleymaniye villages have remained from the Byzantine period (castle).

Armenian Population

“Lying in both shores of the eastern half of Lake Iznik, the kaza of Yenişehir had, in 1914, three Armenian colonies with a total population of 4,750. Two hundred fifty Armenians lived in Nor Kiugh [‘New village’], just outside Nicea/Iznik; 2,500 were to be found in the village of Marmaracık. Finally, in Yenişehir, the seat of the kaza, with a mixed population, there were more than 2,000 Armenians, most of whom earned their living as farmers.”[2]

Nikaia (Iznik)

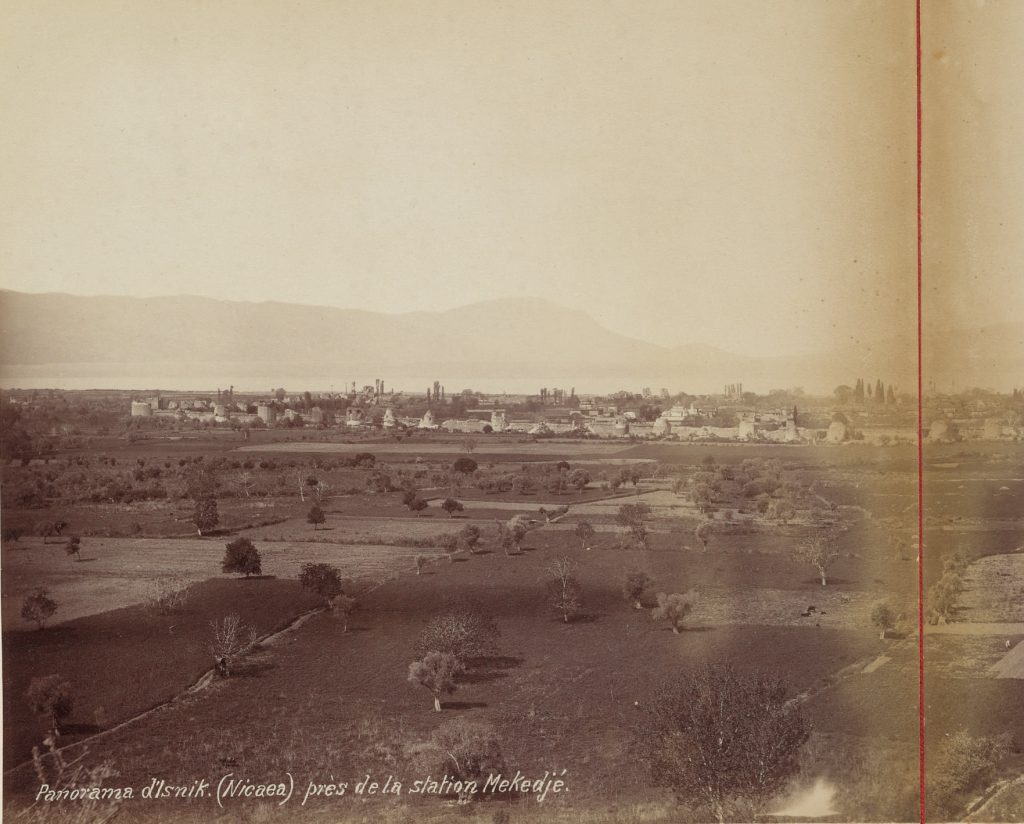

The ancient city of Nikaia (Νικαία; Tr: Iznik), situated at the very east of Lake Askania (Gr: Askania Limne – Ἀσκανία), was established by the Makedonian-Greek king Antigonos I in 316 B.C. on the site of a previous Bottiaeanian settlement by the name Ancore (Ἀγκόρη) or Helicore (Ἑλικόρη); then named Antigoneia (Ἀντιγονεία) in honor of its founder Antigonos, it was soon renamed in Nikaia by the Makedonian-Greek king Lysimachos in 301 B.C. in honor of the mythic ancient Nikaia, daughter of the river god Sangarios and the Phrygian goddess Kybele; Nikaia was a huntress and companion of the goddess Artemis.

In 2018, researchers of an archaeological survey of the German Ruhr University (Bochum) summarized their findings: “Nicaea was a polis of local significance in Bithynia, an ancient region in the north-west of Turkey. The city was subject to the regional reign of the Bithyntian kings before it became the centre of the Roman province Bithynia et Pontus within the Roman Empire. After the divide of the Roman Empire it became the hinterland of the new royal capitals Nicomedia and Constantinople. It also is the one place where the most extensive monumental heritage in Bithynia can be found. The characteristic central position between centre and periphery makes Bithynia a significant case example for specific local characteristics of the cultural process of adaptations in the ancient Mediterranean world.”(3)

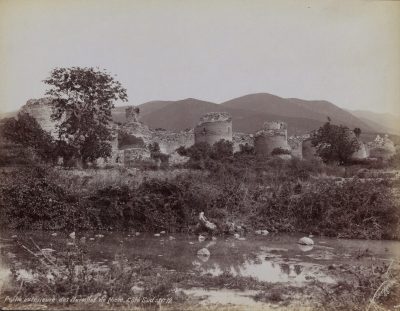

In 78 B.C., Nikaia came under Roman control, was occupied by the Seljuk Turks in 1081, but retaken by the Romans (Byzantines) and crusaders on June 19, 1097, and served as the capital of the East Roman Empire during 1204-1261. After a long siege, it was occupied by the Ottoman Turks on March 3, 1331.

Initially a diocese under the Metropolitanate of Nikomedia, Nikaia (Nicaea) was the site of the First (325) and Seventh (787) Ecumenical Councils. It was promoted to a Metropolitanate by Emperor Valens ca. 370, with six dioceses under its jurisdiction in the 10th century. However, after Ottoman conquest (1331) their number steadily decreased, with none remaining by the year 1600. After Ottoman occupation, the see of the Diocese Nikaia was moved 50 km West to Kios (Tr: Gemlik). According to a 1919 documentation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, it consisted of 26 communities with an overall Greek Orthodox population of 33,470.

Iznik was the most important centre of Ottoman faience production, but was overtaken by Kütahya in the 17th century. In both cities the production of tableware and tiles was mainly in Greek and Armenian hands.

Further Reading: https://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/5900/

Restoring the Byzantine Empire: The Imperial Empire of Nikaia

In 1204 the Byzantine Emperor Alexios V Doukas fled from Constantinople after the crusaders had invaded the city. The son-in-law of Alexios III, Theodor I Laskaris, was crowned Emperor. He fled to Nicaia in Bithynia when he realized that the situation in Constantinople was hopeless.

The Latin Empire founded by the crusaders had insufficient control over the former Byzantine territories, in many places it was non-existent. Therefore, Byzantine successor states were quickly established: the despotate Epirus, the empire Trapezunt as well as Nikaia. Because of its proximity to Constantinople, Nikaia was in the most favourable starting position for the restoration of the Byzantine Empire. Theodoros I Laskaris first suffered setbacks, for example in 1204 at Poimanenon and Prusa (today Bursa). Nevertheless, he established himself in large parts of northwest Anatolia, favored by the battles between the Latin Empire and Bulgaria. In 1206 Theodoros I had himself crowned Emperor of Nicaia. He defeated the Seljuks at Antioch in Pisidia in 1211, when they presented Alexios III as a pretext to expand to the west. He also snatched the Black Sea coast of Bithynia from the emperor of Trebizond (Trapezunta).

Many alliances and peace treaties between Bulgaria, Nikaia, the Seljuks and the Latins were concluded and broken in the following years. Theodoros I substantiated his claim to the diadem of Constantine the Great by appointing a new Patriarch of Constantinople in Nicaia; in 1219 he married a daughter of the Latin Empress Jolante of Flanders. When he died in 1222, he left his successor and son-in-law John III a small but viable state.(4)

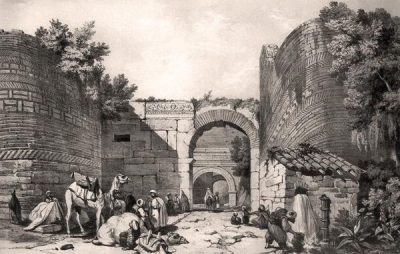

From 1208 until 1261 Nikaia served as capital of the empire, although John III Vatatzes resided in Nymphaion and Magnesia; Nikaia was also the seat of the patriarch and home of many illustrious refugees, notably Niketas Choniates, Nicholas Mesarites, and Nikephoros Blemmydes. Laskarid Nikaia was the scene of frequent synods, embassies, and imperial weddings and funerals and became a center of education, notably under Theodoros II Doukas Laskaris (1221/2-1258), who founded and endowed an imperial school. After the recapture of Constantinople, Nikaia declined in importance and prosperity. Neglect of the eastern frontier provoked a serious revolt in the region in 1262, and in 1265 the whole city panicked on rumor of a Mongol attack. In 1290 Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos arrived on a tour of inspection and restored the walls, but the region remained defenseless against a new foe, Osman. Nikaia held out until 1331, when it fell to the Ottomans after a long blockade. When the Byzantine theologician Gregorios Palamas visited Nikaia in 1354, its Christian population was severely depleted.

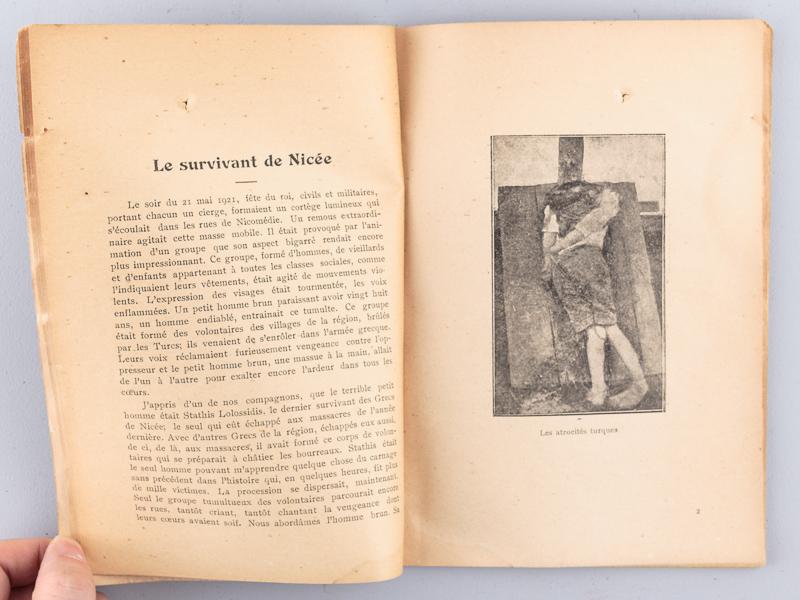

The Iznik Massacres of August and September 1920

In a 1920 documentation by the Ecumenical Patriarchate at Constantinople the situation in the Diocese of Nikaia is summarised in the following way: “This district had for along time been terrorised by Turkish and specially Laz, bands. Robberies in the very streets, raids into Christian communities and carryings-off of Christian notables were none but too frequent.”

On 27 August 1920, Turkish irregulars massacred approx. 600 Greeks of İznik (Grk.: Nikaia). Their slaughtered bodies were later found thrown in wells while others were burnt and found piled up in a cave just outside the town. The town’s church was also destroyed, not before women were raped on the altar.[5] A second massacre took place in late September 1920. The Greek High Commission put the total massacred at Iznik at 600.[6]

Thomas Anastasiadis lived through the Iznik massacre. In an oral interview he recounted:

“For 75 days the chettes [Tr: çeteler] had blocked off the Greek neighborhood of Nicaea. Nobody could leave. They had placed objects blocking the four exit gates of the town. The entire town of Nicaea was closed in. On the 14th of August [1920], on the eve of the feast day of the Virgin Mary, the day on which our church celebrated, the chettes gathered all the Greeks of Nicaea, 87 families, and lead them out of Lefke Kapusu [Gate to Levke; Trk.: Lefke Kapısı], eastwards, to the pastures. There they were all slaughtered with German bayonets. They threw the bodies inside a cave and burnt them. They didn’t spare the church either; they destroyed it. They raped women on the altar. Twenty days after the slaughter, the Hellenic Army entered the town and stayed for 3 days then left. They did not retaliate on the local Turks who were not to blame for what happened.”[7]

The districts of Bursa, Iznik and the peninsula and town of Izmit were terrorised by a group of Kemalist irregulars under the command of a certain officer Cemal Bey, who was also responsible for the massacres of August 27, 1920. A British officer later toured the ruins and reported on October 7, 1920 about Iznik:

“From information in the hands of the Smyrna Division, which is confirmed by previous reports, the whole Greek population of Iznik has been massacred. Apparently the majority of the massacres took place at the end of August – the remainder of the population were killed before the Greeks took the town, i.e. at the end of September. – The number of killed is said to be about 130 families, or about 400-500 men, women and children. (…) All the bodies I saw had been mutilated, apparently they had first had their hands and feet cut off, after they were either burnt alive in the cave or had their throats cut. (…)

Djemal Bey is said to be responsible for these massacres. (…)

The ancient Greek church of Iznik, which dates from 332 A. D. has been thoroughly smashed up, only the walls remaining. (…) It is said that a number of people were massacred inside the church.

The Greek soldiers, who have every opportunity of visiting these places, are not unnaturally bitterly enraged about it.”[8]

Further Reading: https://www.greek-genocide.net/index.php/overview/documentation/132-nicaea

Archbishop Vasilios’ Report on the Iznik Massacre

In his extensive report to the Ecumenical Patriarchate at Constantinople, the archbishop of the Diocese of Nicaea, Vasilios (Basil), gave the details:

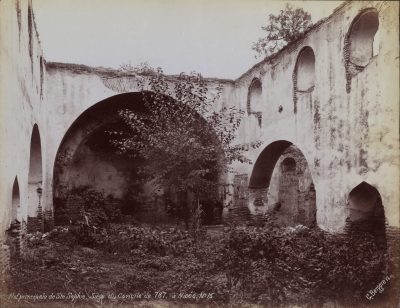

“We visited the famous church [Hagia Sophia] and we found it in ruins. The altar was brought down. The famous altar marble slab was broken to pieces. The church mosaics, except those too high for the profane to reach, were destroyed. Several of the many and ancient icons were broken and their valuable dedicative jewels robbed. (…)

The Turks, not satisfied with the destruction of the historical Christian Cathedral, preceded to the annihilation of the Greek inhabitants of Nicaea. By midnight of August 13th, men, women and children were forced out of their houses and led through the gate of Leuke [Levke; Tr: Lefke Kapisi] to their place of martyrdom. On the way, some of them could not go on, especially the children, and the monsters killed them on the spot and threw some of them in wells nearby, while others were covered up with a little earth. Their bodies could be seen for quite a long time afterwards. Three wells by the roadside were filled with half dead. Later on they were covered with earth, to stop the odour coming out of them. The remaining victims were led to their place of execution, which was outside a large and deep cave and near a smaller one, a little farther away. They were killed outside these caves and then thrown in them, one upon another. Several bodies were found horribly mutilated, those of the women, whose breasts were cut off and their bellies cut open. A young girl was found crucified on a tree; she was afterwards buried by some Greeks of a village nearby.

While the above tragedy was taking place and the two caves were being filled with the dead mutilated bodies of Greeks, a horrible scene was happening in the city and within the court of the church. Some women escaping the persecutions took refuge inside the church, where Nicaea’s only Priest, named Jordan, was present. The women were all slaughtered and their bodies were thrown in the well of the church court, where blood marks can still be seen. The Priest, with a bridle in his mouth, was forced to go about the town on all four, carrying a Turkish boy astride on his back. He then was led to the large cave outside the city, where he was killed, like the rest of his congregation.

Only one Greek soul survived, Olga Thomas Valessoglou of Leuke, a victim of Djemal’s shameless passion. She now is in Kios [Gemlik] under the protection of the Greek staff. She informed me of some of the events that took place in Nicaea between the 6th and the 19th of September.”[9]

List of the murdered Greek families of Nikaia (Iznik)

Based on the information given by survivor Thomas Anastasiadis, the Hellenic war correspondent Konstantinos Faltaits composed an imcomplete list of the victimized families:

Family Nikolaos Anastasiadis; 7 people

Savvas Anastasiadis; 2

Savvas Psomas; 6

Efthimios Psomas; 6

Pavlos Raptis; 13

Phillip Raptis 6

Efstathios Simeonidis; 6

Evsimani Simeonidis; 3

Gregory Vasiliou; 8

Sultana Vasiliou; 5

George Simeonidis; 3

Jordan Simeonidis; 4

Stylianos Hatzivasilliou; 5

Kyriakos Theodorakis; 7

Elenko Keyvelis; 2

Savvas Keyvelis; 5

Michail Papageorgiou; 6

Panagis Papageorgiou; 7

Jordan Papajordan; 8

Demetrios Papageorgiou; 10

Iovakos Favianou; 14

Lazaros Ladas; 5

Ioannis Ambatzis; 6

Emilios Kesisoglou; 4

Sofronios Hatzistavridis; 7

Theofanis Anagnostidis; 3

Demitrios Seferidis; 3

Anastasia Tsakiriadis; 2

Ioannis Tarafopoulos; 4

Konstantinos Kakoulopoulos; 2

Michail Talamopoulos; 9

Matthew Tournazidis; 4

Michail Papazoglou; 4

George Algianos; 5

Konstantinos Papoutzou; 3

Sultana Gaggime; 3

Vasiliki Kontoglou; 2

Angelos Hasapidis; 2

Efthimios Hatzipavlidis; 6

Maria Karayaka; 4

Vasilios Kavoukidis; 4

Christos Sivrisoglou; 5

Hariklia Kalaintzis; 3

Kyriakos Vola; 6

Michail Samaras; 6

Dimitrios Karaoglou; 3

Elizabeth Vasiliou; 5

Stylianos Koutsopoulos; 4

Dimitrios Sideras; 5

George Naftis; 4

Anthi Hatzis; 4

Ioannis Katemlis; 5

George Katmli; 7

Michail Papazoglou; 4

Panagiotis Mavridis; 6

Nikolaos Koulouras; 5…

Achilleas Tzamtzis; 6

Jordan Paschalidis; 4

Chrysafos Potopoulou; 4

George Stavridis; 6

Evdoxia Devrisidou; 5

Stylianos Litourgou; 6

Konstantinos Armoutzis; 3

Panagis Hatzopoulou; 5

Stylianos Hatzopoulos; 6

Apostolos Tapia; 3

Eleni Rokka; 3

Haralambos Yannakou; 10

Aristidis Vafiadis; 5

Jordan Yannakou; 5

Ioannis Karaka; 5

George Sarris; 6

Vasiliki Dimitriadis; 5

Angeliki Saratzikli; 7

Simeon Nikolaidis; 6

Maria Psoma; 3

Sevastos Evstathiadis; 5

Panayiotis Gianopoulos; 6

Theofanis Paritsis; 3

Alexandros Koukoulas; 2

Alexios Papadopoulos; 5

Harilaos Prodromitis; 3

Ekaterina Pasia; 3

Vasilios Hasapidis; 6

Petros Kyriakou; 3

Hariton Alexandrou; 6