The relief of the Sivas Vilayet is mountainous. Three mountain ranges stretch from west to east: Janik (Canik; north), North Taurus (center) and Inner Taurus (south). The territory is crossed by two large rivers from east to west: Halys (Trk.: Kızıl-ırmak – Red River) and Iris (Turkish: Yeşil-ırmak – Green River). The lakes are few; the largest, Ladik, reaches up to 11 km during snowmelt.

The northern part of the province is forested. There are almost all types of coniferous trees. In the lowlands of the sancak of Tokat (Grk.: Evdokia), cherries, apples, walnuts, etc. predominate. Forests are scarce in the central and southern regions.

The territory of province of Sivas is rich in minerals (copper, coal, marble, etc.). There are various mineral springs (Jermuk), of which Sarnaghbyur, Jermaghbyur and Havaz, not far from the provincial capital Sivas, are known.

Administration

In 1403, after a brief interregnum by Timur Lenk, the Ottomans brought Sivas and the adjacent regions again under their control. The town of Sivas became the capital of the Ottoman Rum Eyalet (Roman, i.e. Byzantine Province), including the sancaks of Amasya, Çorum, Bozok (Yozgat), Samsun, Divriği (Tevrik), and Arapgir.

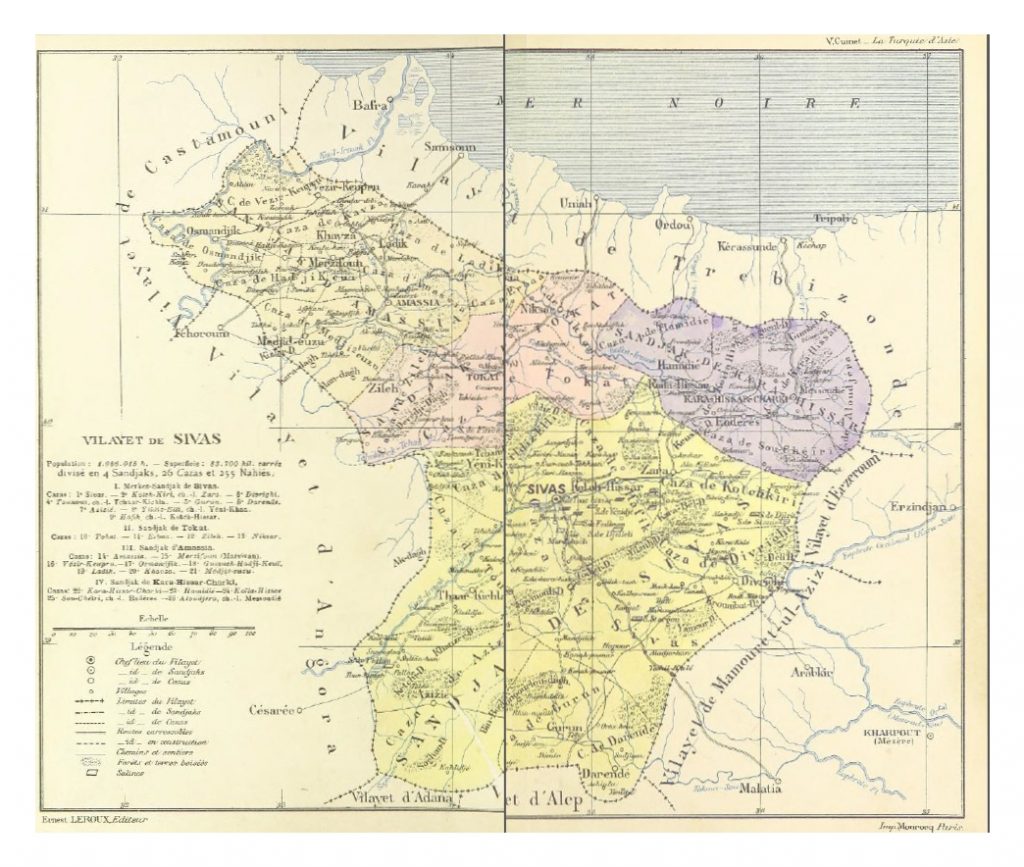

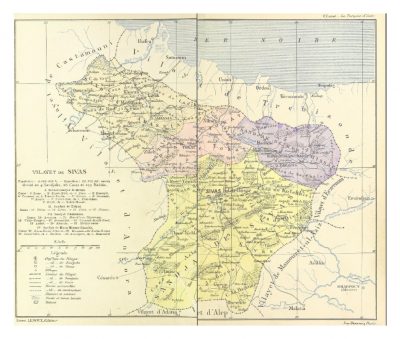

As an Ottoman administrative unit, the Vilayet of Sivas was created in 1864-1867 when eyalets were replaced with vilayets under the ‘Vilayet Law’ (Turkish: Teşkil-i Vilayet Nizamnamesi). In the 1880s, the sancaks of Canik (Samsun), Bozok (Yozgat), Çorum and Arapgir were separated from the province of Sivas, which was then subdivided into the four sancaks of Sivas (with the kazas Sivas, Bünyan, Şarkışla (Tonus), Darende (Tarente), Divriği (Divrik; Trik), Aziziye, Kangal, Koçgiri/Zara, Koçhisar, Gürün, and Yenihan), Amasya (with kazas Amasya, Havza, Mecitözü, Vezirköprü, Gümüşhacıköy, Merzifon, Ladik), Karahisar-ı Şarki (with kazas Şebinkarahisar, Alucra/Hamidiye, Me(h)sudiye/Ma(h)sudiye/Melet, Suşehir [Endires/Enderes, Trk.: Endıres till 1875], Koyulhisar/Kizilhisar), and Tokat (with kazas Tokat, Erbaa, Zile, Niksar, Reşadiye) with overall 27 kazas.

The province of Sivas was one of the Six Provinces (Vilâyat-ı Sitte) of Western Armenia and one of the most densely populated provinces in Asia Minor. At the beginning of the 20th century, the province covered an area of 32,308 square miles (83,680 km2).

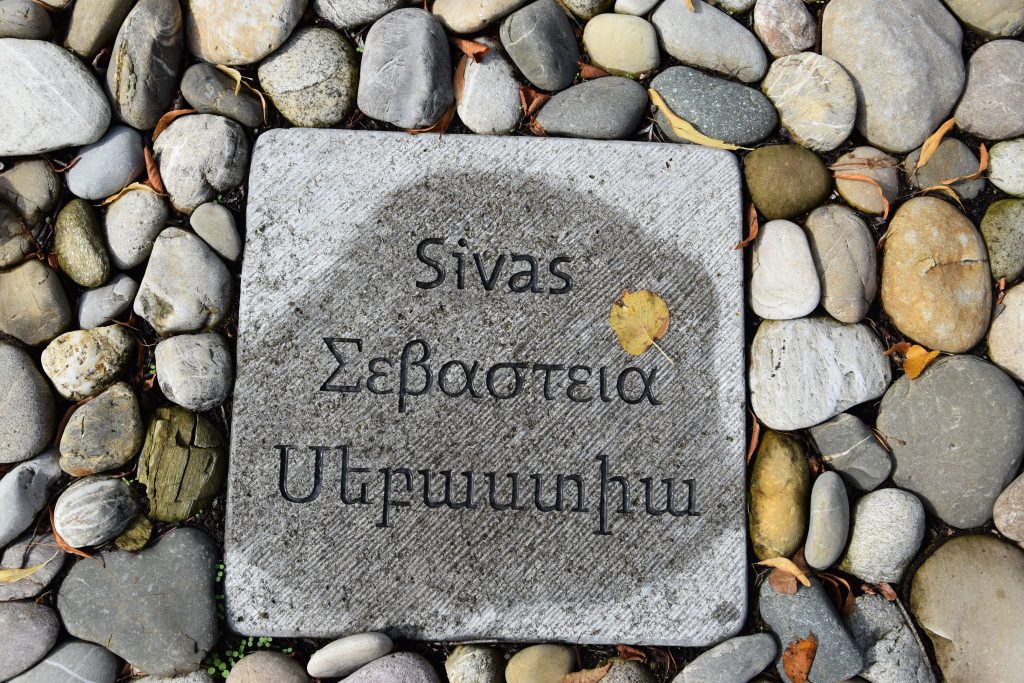

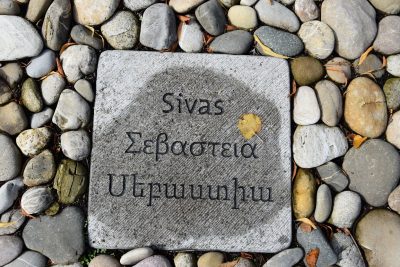

Toponym

According to Strabon, Sivas was founded by Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus after his victory over Mithridates VI Eupator of Pontos and in the course of the reorganization of the eastern Mediterranean under the name Megalopolis (corresponding to Pompeius’ honorary name Magnus) by merging older settlements. Coin legends show that it took the name Sebasteia (Σεβάστεια; Latin augustus = Greek σεβαστός) in honor of Emperor Augustus between 1 and 6 C.E., and finally passed into Roman administration in 64/65 C.E. The Turkish and Kurdish forms of the name are derived from the Greek toponym.

Population

The area of Sivas has been the cradle of Armenian tribes since ancient times. In the 6-5th centuries B.C. Greeks entered from the north, the number of which increased in the Hellenistic era (4-2nd centuries B.C). In the 1st century B.C., when Rome occupied the territory of the province of Sivas, the Greceophone population dominated in the western part, and Armenians in the eastern one. In the 11th century Armenians, avoiding Turkish invasions, moved en masse to Lesser Armenia. The largest migration took place in 1021, when King Seneqerim (Senekerim) Hovhannes Artsruni of Vaspurakan moved with his subjects to Sivas. Since the end of the 11th century, Turkish tribes have settled there.

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the population as 996,126. The accuracy of the population figures ranges from ‘approximate’ to ‘merely conjectural’ depending on the region from which they were gathered.

According to Vital-Casimir Cuinet (1890), the total population of the Sivas province numbered 1,086,015, of whom 170,433 were Armenians, 76,068 Orthodox Greeks, 559,680 Muslims (Turks, Turkomans, Circassians) and 279,834 Kizilbash.[1] According to the 1918 Ethnological Map Illustrating Hellenism in the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor by the Greek archaeologist Georgios Soteriadis, the Greek-Orthodox pre-war population was as high as 99,376.[2]

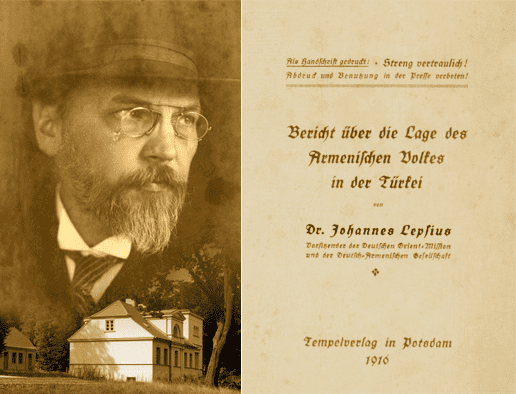

Johannes Lepsius mentioned in his 1916 report similar figures as Cuinet: “The Vilayet Sivas counted 271,500 Christians among 1,086,500 inhabitants, namely 170,500 Armenians, 76,000 Greeks and 25,000 Syriacs. The Muslim population consists of two-thirds Sunni Turks, Turkmen and Circassians, and one-third Shiite Kizilbashis.”[3] The Muslim population included 10,000 muhacirler [refugees, immigrants], who had settled in the region in the wake of the Balkan War.[4]

Armenian authors gave higher estimates for the Armenian population, with the Armenian archbishop and lecturer Mesrob Krikorian considering the data of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarch at Constantinople, Ormanian, of 200,000 Armenians the most probable.[5] Raymond Kévorkian gives the total population of the Sivas province with approximately one million in 1914, “including 204,472 Armenians and about 100,000 Greeks and Syriacs. The Armenians in the urban centres were the most conspicuous, but non-negligable numbers of Armenians inhabited the countryside as well; they lived in some 240 villages and hamlets, boasting 198 churches, 21 monasteries, and 204 schools with a total enrolment of 20,599.”(6)

An incomplete list of Greek settlements in the Sivas province includes the four settlements of Σεβάστεια – Sevasteia

Αγορέν – Agoren

Αλτίνογλου τσιφλίκ – Altinoglou tsiflik [Altınoğlu Çiftlik]

Γενίχταν – Yenikhtan [Yenihan / Yıldızeli?].[7]

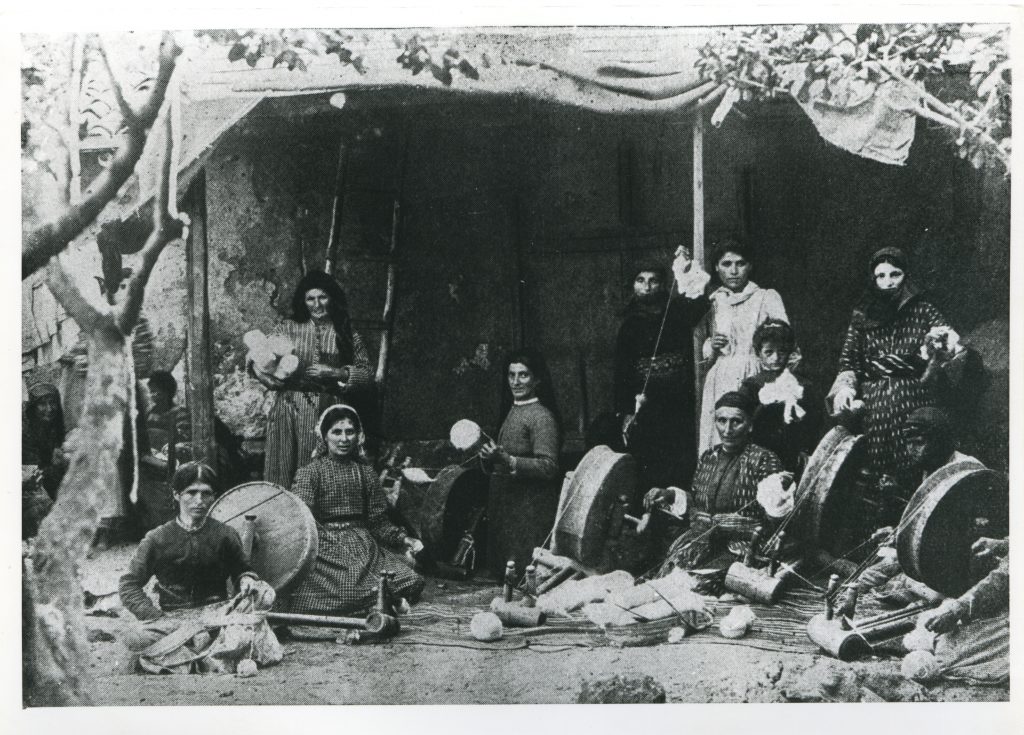

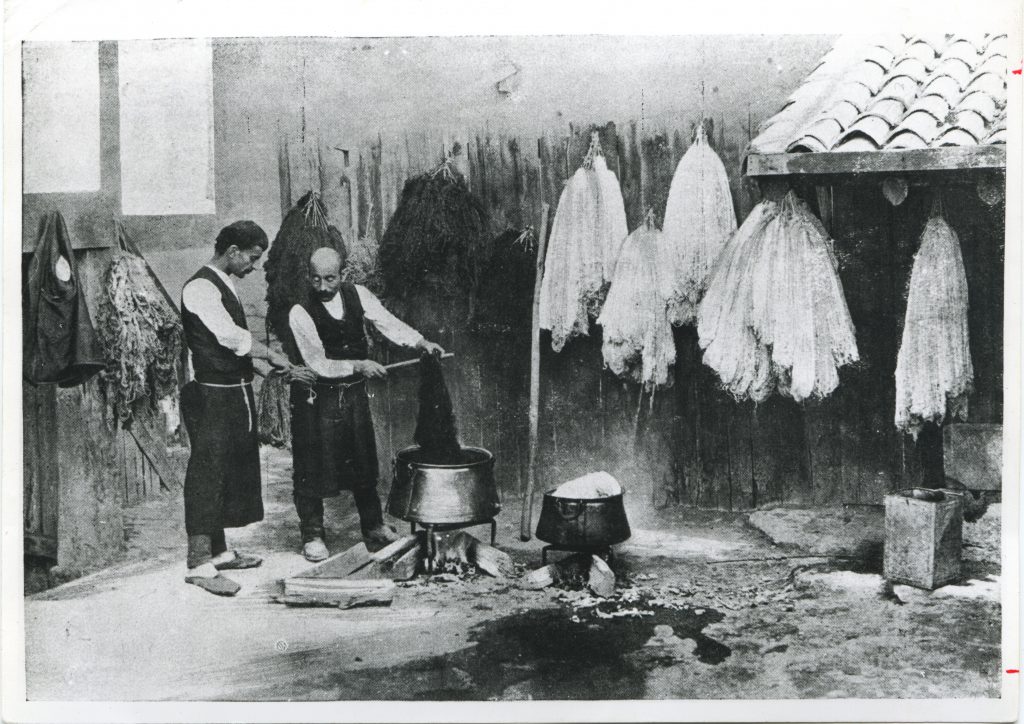

The villagers were engaged in the cultivation of grain, rice, lentils, peas, tobacco, horticulture, beekeeping, winemaking, animal husbandry, and handicrafts.

In the 19th century industrial enterprises, textile, match, leather, iron, wine, copper smelters, and dye factories were established. They imported copper, tin, aniline dyes, coffee, leather, brandy, iron, mahogany, etc., exported grain, flour, hemp, fresh fruit, wool, etc. Industry, crafts and trade were mainly concentrated in the hands of Armenians.

“Many others were occupied in various handicrafts, mainly in the printing of cotton hangings, making belts, the blacksmith’s art, painting and dye-works, watch-repairing, sewing, shoe-making, carpentry and mason’s work, and in carpet and textile weaving. (…) More wealthy Armenians were engaged in commerce and money-exchange. The trade of the province was principally in their hands and they were regarded as shrewd merchants. (…)

It is noticeable that the Armenians contributed also, officially and unofficially, to the public hygiene of Sivas. There were man chemists and physicians serving different parts of the province, of whom Sarkis Parseghian, Hindlian, Levon Hiwsisian, Miridjan Karmirian, Karapet Pashayan and Yarutiwn [Harutyun] Vezneyan can be named.”[8]

Armenians and Greeks in the public administration of Sivas Province

“The main fields of Armenian participation were the departments of political administration, finance, justice, and the secretariat. (…) In the agriculture of this province, particularly of the central sancaks, Armenians were employed by the forestry board, by the inspectorate board of agriculture and crafts, and as forest rangers.

The Greeks in Sivas did not take a large part in the public administration. Their participation was considerable only at the centres of the sancaks, as well as in the kazas Merzifon, Ladik and Havza in Amasya, at Niksar in the sancak Tokat, and in the kazas of Hamidiye and Alucra in Şebinkarahisar. Greeks were included in the administrative councils, education committees and judicial courts. They were employed also as provincial translators and as clerks in the chief secretariat. Their share was greater financial affairs, to which they contributed by working in the departments of tobacco monopoly, public debt administration, customs, and in the branch of the Agricultural Bank. (…)

After the Reforms, the Greeks were used by the Ottoman Government to patronize the Christian population. They were given higher positions in the political administration as assistants to the ‘Vali’ [provincial governor] and to the governors of the other sancaks and some kazas.”[9]

History

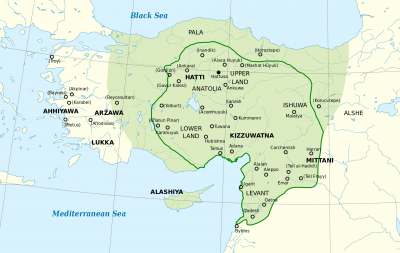

Sivas earliest settlement dates back from 7000 to 5000 B.C. The Hittites, whose settlement remains are found at Topraktepe near Sivas, ruled there from 1600-884 B.C., then for about 100 years the Phrygians (800-695 B.C.). The Phrygians were replaced by the Lydians. These lost the territory to the Persians in 546 B.C. The Persian Empire was subdued by Alexander the Great, so Sivas was ruled by the Diadochi until about 17 A.D. Under Emperor Diocletian (reigned 284-305), Sivas was the capital of the Roman province of Lesser Armenia, or Armenia Minor, which in the 4th century was subdivided in two provinces: First Armenia (Armenia Prima), which contained most of Lesser Armenia, and Second Armenia (Armenia Secunda) that comprised all the southern tracts which had been added to Lesser Armenia. Until 395 Sivas remained part of the Roman Empire, then Byzantine until 1075.

After several years of negotiations, Emperor Basileios II compensated Seneqerim Hovhannes Artsruni, king of Vaspurakan in southern Armenia, with the territory of Sebaste in 1021. Seneqerim Hovhannes moved his court, high clergy and 14,000 families to Sivas and administered it as a Byzantine vassal.

In the 11th century, the first Turkish tribes appeared in Anatolia. In 1059 the Seljuks invaded Sivas, and sacked it, massacring many of the population and burning the town. The sons of Seneqerim, Atom and Abu Sahl (Apusahl), escaped to Gabadonia (Develi).[10]

From 1142 to 1171, the Danishmend dynasty ruled over Sivas. In 1174, the Seljuks under Kılıç Arslan II conquered the city and, among other things, had the Ulu Cami built in 1197. Sivas, along with Konya, served for a time as the Seljuk capital. In 1232, Sivas, like large parts of Eurasia, was invaded by the Mongols. The Mongols were followed by the Beylik of Eretna, which was put to an end by Kadi Burhan al-Din. In 1398 the Ottomans under Sultan Bayezid I conquered the city and lost it in 1400 to Timur, who attacked Sivas “with huge armies, underminded the walls of the town, captured the people and put many of them to death. He was particularly cruel to the Armenian regiment which had strongly resisted them on behalf of the Ottomans.”[11]

In 1403 the Ottomans managed to recapture Sivas. It served as the capital of the Ottoman Rum Eyalet until 1864, when it became the capital of the now independent Vilâyet Sivas.

“Sebasteia became Sivas, first in Seljuk, then in Danishmend hands. It flourished as a trading city and its Armenians seem to have prospered under both régimes. (…) But the final disaster came in 1400 when Timur took Sivas after a twenty-day siege. He dealt with the city in characteristic ruthlessness. Until recently, travelers were shown the ‘Black Earth’ in Sivas, the common grave of the 4,000 Armenians who had helped in its defense. Sivas never recovered, although it remained an Armenian center until this [20th] century. After the year 1400 many Armenians fled to Trebizond where there is evidence of a refugee problem for a couple of decades.”

Excerpted from: Bryer, Anthony: The Armenian Dilemma. “History Today”, Mai 1966, p. 351f.

Further Reading

Hrant Dink Foundation: Sivas Research and Fieldwork

Vahakn Keshishian, Koray Löker, Mehmet Polatel (Ed.s): Sivas with its Armenian Cultural Heritage. Translated into English by Ayşe Aksakal, Betül Kadıoğlu, Nazife Kosukoğlu, Cansen Mavituna, Linda Stark, Cansu Yapıcı. 1st edition – September 2018, 163 Pages

Download the book: https://hrantdink.org/attachments/article/1405/Sivas_Raporu_new.pdf

Destruction

“The 30 March 1913 nomination of a new vali, Ahmed Muammer Bey [1874-1928] – he held his post until 1 February 1916 – seems to have exacerbated the degradation of the non-Muslims’ situation. In accordance with the wishes of Young Turk circles (…) the vali initiated a policy of boycotting Christian entrepreneurs and merchants after the Ottoman defeat at the hands of the Balkan coalition. Muammer, a native of Sivas and son of magistrate, played a decisive role in creating a network of Ittihadists clubs in his native vilayet from 1908 on. (…) Muammer also attacked religious institutions, such as when he confiscated the land belong to the monastery of St. Nshan, located near the city, in order to build a barracks for the Tenth Army Corps there. (…) In April and May 1915 several suspect fires broke out, one after the next, in the bazaars of Merzifun/Marzevn, Amasia, Sivas, and Tokat. (…) The most symbolic act was the arrest, around 15 March, of 17 political leaders and teachers in Merzifun and Amasia, among them Kakig [Gagik] Ozanian, Mamigon [Mamikon] Varzhabedian, and Khachik Aramian – who were immediately transferred to Sivas (…).”[12]

“During June and July 1915, most of the Armenians of Sivas vilayet were either killed or were deported in ways designed to bring about their deaths. In September 1919 the American Military Mission to Armenia arrived in Sivas, en route to destinations further east. They discovered that of the possible 200,000 Armenians of Sivas vilayet before the war, only some 10,000 remained. Those survivors were mostly living in abject poverty, unable to reclaim their property, and fearful of new massacres (in 1919 Sivas was a center of the Turkish Nationalist movement). Most were making preparations to leave. There were 1363 Armenian orphans in Sivas, in orphanages of the American-run Near East Relief.”[13]

Johannes Lepsius: House searches, looting and arrests before the deportation in the Sivas Vilayet

“

“Before the general deportation, conditions in the Vilayet Sivas were the same as in the Vilayets Trapezunta [Trabzon] and Erzurum. Organized gangs plundered the villages. The gendarmes entered the houses under the pretext of looking for weapons, looted, raped the women and tortured the peasants in order to extort money. Anyone who complained was arrested. All military conscripts, including those who had bought the legal military exemption tax (44 Turkish pounds, about 800 marks for a person) through ‘bedel’, were taken out and sent out as porters and road workers. When it was revealed that the porters were dying of starvation from lack of food and that the road workers were being shot by their Muhammadan comrades, many of those who had not yet been drafted fled to the mountains, whereupon the government torched their homes.

In these, as in all other vilayets, disarmament was carried out systematically before the massacres and deportations began. Disarmament in the villages proceeded in such a way that, without prior announcement or public notice, the villages were surrounded by gendarmes and two or three hundred firearms were demanded from the population at will. If the village sheriff and the elders could only muster about 50, the notables were notched and maltreated with the bastinado. In the city of Sivas, five hours were given for the delivery of the weapons. If anything resembling a weapon was found in the houses afterwards, the houses were set on fire and the inhabitants were killed.

Then the arrests of the notables and Dashnaktsakan began in the cities. In Sivas 1,200 and in Şebinkarahisar 50 were arrested and taken away without interrogation. During the house searches, the authorities searched for documents or letters from which evidence of anti-government sentiment or attacks of any kind could be deduced.

Although nothing was found anywhere, the authorities spread the false rumor that hundreds of bombs and thousands of rifles had been discovered among the Armenians and that the Dashnaktsakan had tried to blow up the powder magazine. The government did not need to provide proof to the gullible Muhammadan population, but it achieved the intended incitement of the Muhammadans against the Christians.

After the intellectuals were arrested, the order of general deportation was issued. The danger threatening the Armenians was exploited by the officials to great extortions under the pretense that they had it in their hands to prevent the deportation. The Armenians of Tokat gave the mutesarrıf 1,600 Turkish pounds (Approx. 30,000 marks) to be spared from deportation.”[14]

Deportation of Pontian Greeks to the Sivas Vilayet during the First World War

The Russian military advance and occupation of the eastern half of the Trebizond Province offered the pretext for the deportation and expulsion of the Greek Orthodox population from the Black-Sea provinces of Trebizond and Kastamonu to the neighboring province of Sivas.

In the Heriana-Kelkit region of the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Khaldia with the exception of 200 persons the inhabitants of the following villages were deported to the Sivas province: Upper Tarsos, Lower Tarsos, Melen, Oulou-Seiran [Ulu-Seyran], Makrolith, Tsaoul, Zimon, Kum-patour, Papoutz, Tzapoutli, Pintzanta, Touman- oloughou, Somki, Parotzi, Zangar, Sion.

“Houses, churches and schools were first plundered and then burnt down. Moveable property was pillaged, and landed property sequestered by the Turks.”[15]

In the Kerdjenissi Region of the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Colonia, the following villages were deported: Kadıköy, Hifahiye, Kondylia, Pistour, Alacahan, Mondolas, and Mentemrli. “In July 1917, the Müdir came to Kadıköy with a number of armed Turks and ordered the Christians to evacuate the place within two days. This same order was given to the six other villages. Thousands of persons, who had been subjected to many trials, were now dispersed among the Turkish villages of Sivas, where nothing but their destruction awaited them. During the deportation, massacres took place, rape was committed, churches desecrated, while small children were carried away under the pretext that the Turks wanted to protect them.”[16]

In the Aloutzara Region of the same Diocese of Colonia the four villages Hindjihi, Anastos, Alissix, Kamışlı. “The evacuation of these villages took place, simultaneously with that of the preceding ones; their inhabitants took refuge in Sivas, Gangra [Çankırı] and Castamouni [Kastamonu]. Many old men and women and children died of hunger and cold in the mountains.” [17]

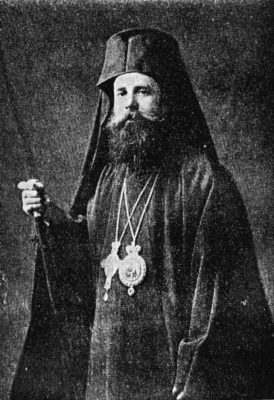

Under date of 12 October 1918, Archbishop Chrysanthos (born Χαρίλαος Φιλιππίδης – Kharilaos Philippidis; 1881-1949), the Greek Orthodox Metropolitan of Trebizond since 1913, wrote: “On the eve of the fall of Trebizonde [Trebizond; Trk.: Trabzon] the Vali [provincial governor] quitted the town, entrusting me, by official decree dated 3rd April, 1916, with the administration of the country. On the 5th April, the Russian troops entered the town, and equally trusted me with the temporary government of the Region. The Bishopric made use of this power, and also the prestige the Metropolitan enjoyed with the Russian military authorities, for the safe-keeping of the life, honor and property of the Turks, all of which were exposed to numerous dangers.(…)

The Bishopric, as well as the Christian element of the Diocese, made it their duty to protect the Moslems of the Vilayet of Trebizonde. (…)

And, while our religious authorities, and the Greek element in general, were exercising their benevolent influence for the benefit of the Moslems, the Turkish Government brutally expelled from their homes all the Christians[18] who had remained beyond the Russian front, in Elevi and Tripoli, together with all the Greeks from Pontos, and forced them to emigrate to Sivas in the middle of winter, and through mountains covered with snow, thus exposing them to certain death. Out of 1,250 inhabitants of Elevi, only 150 survived, and out of 2,300 of Tripoli proper, about 200. The Christians from the district of Tripoli numbered 30,000. Of these only 1,500 to 2,000 persons were left alive.”[19]

Expulsions of Greeks from the Province of Kastamonu began in September 1917, with the exception of some 2,500 persons, who went to by sea to Trebizond and thence escaped to Russia.[20] On 15 March 1917 the Greek Orthodox Metropolitan of Amassia wrote:

“My latest information regarding the fate of the exiled is distressing. The conditions under which the inhabitants of our villages have been expelled are made known to you in my previous reports. After the houses were burnt down, and the plundering of their wealth and furniture had been affected, they went away penniless and deprived of everything. The Turkish villages, in which they are penned up like cattle, are poor, and the inhabitants will not consent to give anything to the ghiavours [giaour or gawur] (infidels). On the other hand, the Government have not taken any care of them, so that the program of extermination succeeds marvelously. Now, on the basis of good and positive information, I inform you that two-thirds of the Christians expelled live perished in the Turkish villages of Angora. The remaining third are rapidly following the rest. The same fate applies to the Christians in the vilayet of Sivas, who had been expelled from the regions of Tripoli, Kerassounde [Giresun], Sinope, and Ineboli, to the vilayet of Castambol [Kastamonu]. It is impossible for me to describe the tortures to which these unfortunate people have been exposed, only because they are Christians and Greeks, during the days of expulsion. I should possibly be accused of exaggerating were I to relate only part of the atrocities committed, such as the abduction of young girls and the massacre of women and children, especially around Erekli [Ereğli], Kourou-keudje [Kuru-köyce?], etc.”[21]

Writer and officer Mehmet Rauf (1875-1931): Deportation of Pontian Greeks from Bafra and Alaçam to the Sivas Vilayet (November 1921)

„On November 22, in Çorum, we witnessed an extremely brutal event.

The Greeks of Bafra and Alacam had been displaced because of general massacres; the men were separated from the others.

Thus, thousands of women, children, infants and a few elderly men, all in a wretched and miserable state, were taken to Sivas under the surveillance of gendarmes. But the state of these Greek women, children, babies and elderly men was so miserable and pitiable that it was impossible for a person not to feel compassion for them, regardless of ethnicity. In the bitter cold, in snowstorms and icy rain, one would see these innocent human beings marching on with bleeding bare feet and ragged clothes. One would see women holding their babies in their arms, and dragging crying children along. On the way, bands sent for this purpose stripped them and slaughtered them. Every day, the thousands of women, children and old men would decrease in number due to the slaughters, starvation, exhaustion and the cold; most, probably none, will reach Sivas alive…“[22]

Report by Dr. F.D. Yowell, director of the Near East Relief unit at Harput, about Greek deportees in Sivas (May 1922)

“Conditions of Greek minorities are even worse than those of the Armenians. Sufferings of the Greeks deported from districts behind the battlefront are terrible and still continue. These deportees began to reach Harpoot before my arrival last October. Of thirty-thousand Greek refugees who left Sivas, five thousand died on the way before reaching Harpoot. One American relief worker saw and counted fifteen hundred bodies on the road east of Harpoot.” [23]