Toponym

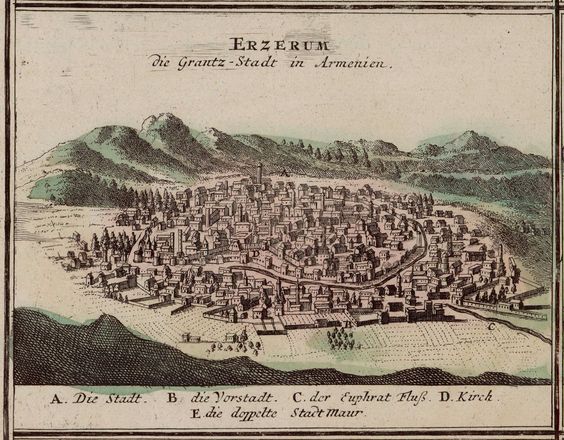

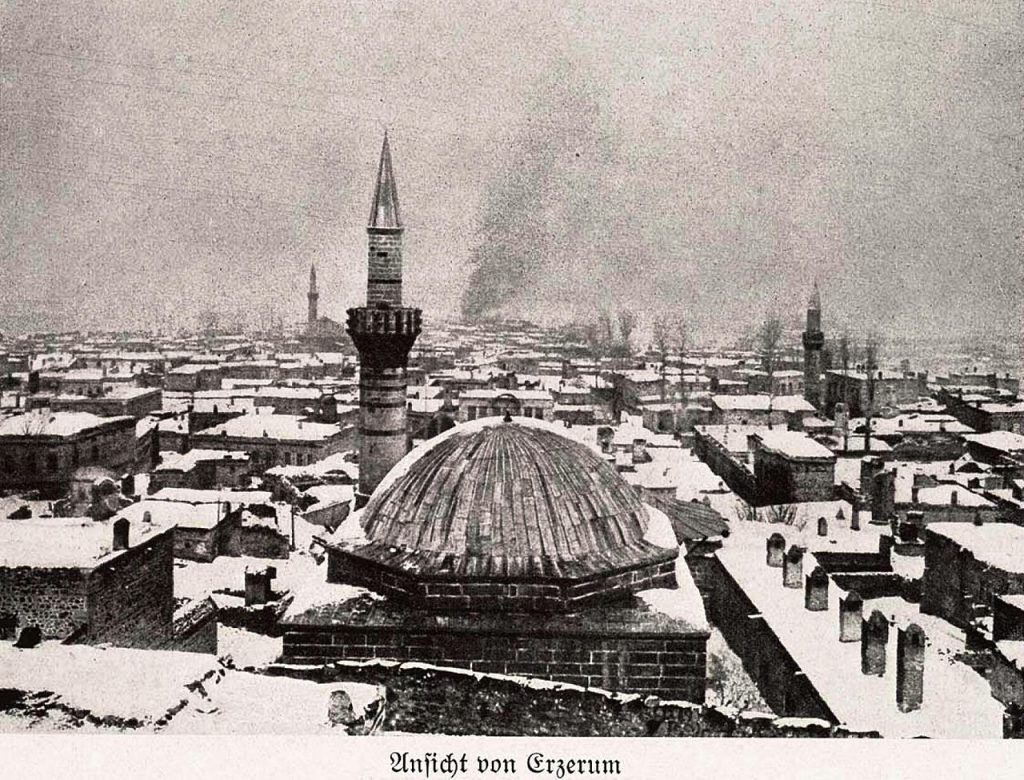

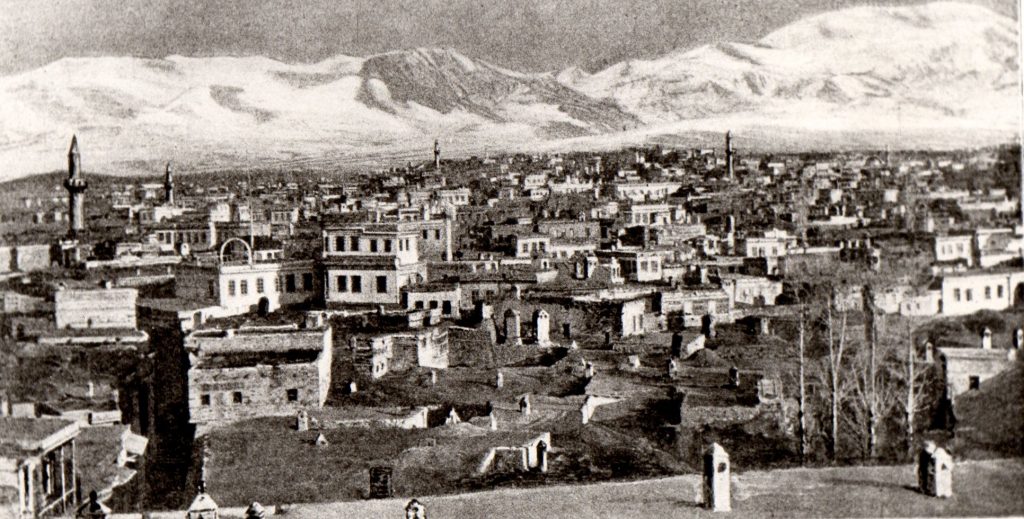

The Ottoman border province (vilayet) of Erzurum (also called Erzerum) corresponds approximately to the High Armenia (Բարձր Հայք – Bardzr Hayk’/Hayq), or ‘Karnoy ashkharh’ (country of Karin) of ancient Armenia. The city of Erzurum was likewise called in Armenian Karin Kaghak (Karin City) which became Kalikala in Arabic. According to another explanation of the name, the Arabic toponym Kalikala derives from Kali, the wife of a local Armenian king. In about 421 the city of Karin was renovated and officially renamed Theodosioupolis, after the Byzantine emperor of that time.

In 1047, when the Persians captured the ancient Armenian town of Ardzn (also: Arzan, Arzen; Armenian: Արծն; 15 km north-west of Karin), the population moved to Karin/Kalikala and gave it the name Ardzn al-Rum (‘Ardzn of the Romans/Rhomaeans’), which through misinterpretation became Arz a-Rum or Ard al-Rum, ‘the land of the Romans/Rhomaeans’.[1]

Administration

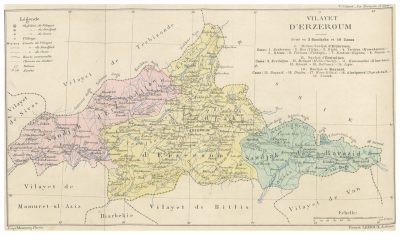

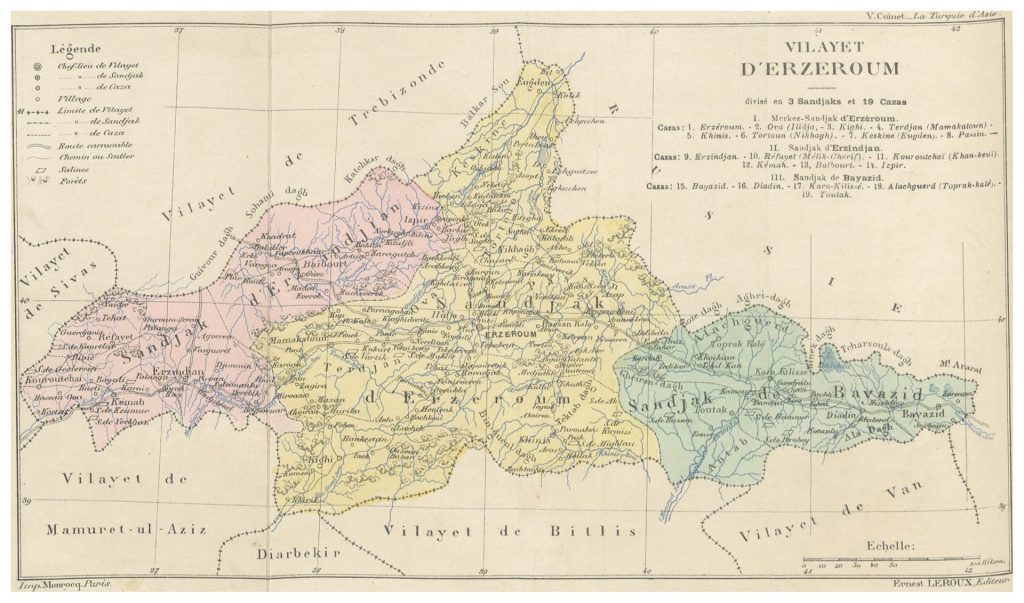

In the second half of the 19th century the territorial composition of the province of Erzurum underwent several changes. In 1865, it was made an eyalet (government-general) which included nearly the whole of the north-eastern part of Asia Minor. In 1875 the eyalet was divided into six provinces (vilayets): Erzurum, Van, Hakkari, Bitlis, Hozat (Dersim) and Kars-Çildir. In 1888, by Imperial order Hakkari was ceded to the province of Van, and Hozat to Mamuret ül-Aziz (today’s Elazığ), while the sancak of Bayburt, remaining in the Erzurum province, was attached to Erzincan. Consequently, the vilayet of Erzurum consisted of three sancaks and 19 kazas, the sancaks being Erzurum (with the eight kazas of Erzurum, Ovacik, Kiğı, Tercan (Mamahatun), Hınıs (Khnus), Tortum, Yusufeli (Kiskim), Hasankale/Pasinler), Erzincan (with the six kazas of Erzincan, Refahiye, Kuruçay, Kemah, Bayburt, Ispir) and Doğubayazit/Beyazit (with the five kazas of Doğubayazit, Diyadin, Ağri/Karakilise, Eleşkirt, Tutak/Entap).[2]

The Kars and Çildir regions were lost in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and ceded to the Russian Empire, which administered it as the Kars Oblast until 1917.

In the late 19th century, Erzurum Vilayet comprised an area of 29,614 square miles (76,700 km2).[3]

History

The region of Karin/Erzurum fell under Roman rule when Armenia was divided between the Roman and Persian empires in 387. In 536, Emperor Justinian I made the country of Karin a province and named it First Armenia (Armenia Prima). About the middle of the 7th century it was occupied by the Arabs, but remained the cause of much fighting between them and the Byzantines for the next three hundred centuries. In 1201 Erzurum fell into the hands of the Seljuks, in 1241 or 1247 into those of the Mongols. Only in 1473/4 as the result of the battle of Tercan against the Ak Koyunlu Uzun Hasan the Ottomans took possession of Erzurum under the Sultan Mehmet II. From that time Erzurum formed an important Ottoman ‘paşalik’. In 1877 it was occupied by the Russians, who soon withdrew after the Treaty of Berlin (1878).[4]

First World War

“The vilayet of Erzerum was the major theater of the fighting between the Russians and Turks and, as such, constituted a central strategic stake of the First World War. The fortress of Erzerum and the surrounding plain constituted the rear base of the Third Army, which had its headquarters in Tortum, north of the regional capital. With the failure of the Turkish offensive in winter 1914-15, the Third Army was decimated and the Ottoman general staff had to make a strenuous effort to form new unities. (…) The command of the Third Army had consequently been entrusted to Kamil, a former classmate of the minister of war [Enver]. From the moment he took office in May, the new vali [provincial governor] of Erzerum, Tahsin Bey, had also been confronted with a typhus epidemic that was weaking havoc on the soldiers and the civilian population (…).”[5]

Population

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the population of the Erzurum vilayet as 645,702. The accuracy of the population figures ranges from “approximate” to “merely conjectural” depending on the region from which they were gathered. In all kazas of the province, Muslims (Sunni and Alevi) were the majority, with the lowest percentage of Muslims (64%) in the kaza of Hınıs. Most of the Protestants and Catholics were Armenian.

In 1890, the French geographer V. Cuinet gave the following statistics for the province of Erzurum: In a total of 645,702, the number of Muslims was 500,782, whereas Armenians numbered 134,967 (including 120,273 Apostolic Armenians, 12,022 Catholic Armenians and 2,672 Protestant Armenians) and Greek Orthodox Christians 3,725.[6] The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople and the almanac Theodik estimated the Armenian population of the Erzurum province as 215,000. Based on this information, Johannes Lepsius wrote in 1916:

“The Vilayet Erzerum counted among 645,700 inhabitants 227,000 Christians, namely 215,000 Armenians and 12,000 Greeks and other Christians. Of the Muhammadan population, 240,700 are Turks and Turkmen respectively, 120,000 Kurds (45,000 sedentary, 30,000 Sazakurds and 45,000 nomadic Kurds); 25,000 Kizilbashis (Shiites), 7,000 Circassians and 3,000 Yazidis. (…) In the cities of Erzurum, Erzincan, Bayburt, Khinis, Tercan, Armenians made up one-third to one-half of the population, and in the individual rural districts, more than one-half of the population.”[7]

M. Krikorian argued: “We can conclude that the mean of the figures given by Fraşeri, Cuinet, Ormanian and Lepsius, for Armenians, and the total population of Erzurum, i.e. 150,000 and 624,385, is the most realistic approximation possible. This means that 25 per cent of the total population were Armenians, which agrees with the figure given by [the British Consul R.A.O.] Dalyell.”[8]

As the data of V. Cuinet and J. Lepsius illustrate, the statistical data for Greek Orthodox Christians in Erzurum province vary by more than a factor of three.

Trades and Crafts of Armenians

“The Armenians in the country districts of Erzurum were occupied in agriculture, but not many of them actually owned land. Heavy taxation, banditry and oppression by Turkish and Kurdish chiefs had deprived the Armenian villagers of their hereditary estates. Therefore those who had no plot or farm of their own worked on government land or for other landowners. After the payment of the government tithe, the remainder of the crop was divided between proprietor and the villagers in varying proportions according to the terms of their agreement.

The majority of Armenians were, however, concentrated in the towns and occupied in trade and various crafts. In 1862 [the British Consul R.A.O.] Dalyell reported:

‘The mercantile class in the towns [of the ‘eyalet’ of Erzurum] is accordingly, principally Christian, who generally own their own houses, or shops; but it is to be observed that it is by no means rare in this part of Turkey for Christians to possess even considerable land property.’”[9]

Destruction

Armenians

(For the destruction of the Armenian population of the city of Erzurum cf. under ‘Kaza Erzurum’)

In September 1914 the recruitment of common criminals released from prison by decree of the Minister of Justice, and the formation of the Special Organization (Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa) squads started. The command center of the Special Organization was installed at Erzurum under the jurisdiction of the 3rd Army to operate in the provinces of Erzurum, Bitlis, Van, Diyarbekir, Mamuret ül-Aziz (Harput), Trebizond, Sivas, and the district of Canik.[10]

“In the 3rd Army’s jurisdiction, which was present in the six eastern provinces, the army committed genocidal acts against the civilian populations (…) in the regions of Erzerum, Van, and Bitlis, where the Armenian population was significant.”[11]

In December 1914 Armenian priests and peasants were murdered by troops of the Ottoman 3rd Army in villages on the Erzurum plain, as recounted by the German Vice-Consul, Dr. Paul Schwarz.[12]

On 10 February 1915, the Deputy Director of the Ottoman Bank’s headquarters at Erzurum, Setrak Pastermadjian, was stabbed in the street by two soldiers. The German General Posseldt, the local military commander, saw that the perpetrators were not arrested although their guilt was widely known.[13] The judicial investigation into the murder of Setrak Pastermadjian has been soon closed; one assassinator has been set free while the second murderer has not been brought to justice at all.[14]

In the end of March 1915, four thousand villagers from Ekabad, Hertev, Hasankale, and Badidjavan, from the High Pasın (Armenian: Basen) region (province of Erzurum) were deported by the army to Mamahatun for “security” reasons[15]. On 21 April 1915 the head of the Special Organization, Bahaeddin Şakir, returned to Erzurum. He set up a “special committee for deportation,” whose leadership is entrusted to the Secretary-General of the province, Cemal Bey.

On 24 and 25 April 1915 two hundred locals were arrested in Erzurum and interned. On 26 April thirty of them were “transferred” to Erzincan, but executed en route.[16] On 5 May 1915 the order to deport Armenians from the province was transmitted to the Governor of Erzurum.[17] On 13 May 1915 the Ottoman Council of Ministers made the official decision to deport the Armenian population of the provinces of Erzurum, Van, and Bitlis. Subsequently, on 16 May 1915 the 30,000 Armenian villagers from the Erzurum plain were deported in three large caravans to Mamahatun. They were exterminated near Erzincan by a Special Organization squad.[18]

On 23 May 1915 the Minister of Post and Telegraphs decreed that all Armenian employees of the Post and Telegraph Services in the provinces of Erzurum, Ankara, Adana, Sivas, Diyarbekir, and Van be removed from their offices.[19]

On 24 September 1915, the US-Consul at Harput, Leslie Davis, discovered several large mass-graves around the Gölcük lake (Hazar Gölü today). They were filled with the corpses of thousands of deportees from Erzurum.[20] Several hundred Armenian conscripts that had been added to a labor battalion were shot on 15 February 1916 in the neighboring gorge of Aşkale (province of Erzurum). [21]

At the end of 1919, there were 1,500 survivors of province of Erzurum.[22] In spring 1920, the social service branches of the Armenian Patriarchate at Constantinople estimated that 3,000 women and children remained captive at Erzurum.[23]

Further Reading

Report by the German Administrator in Erzurum (Erwin von Scheubner-Richter) to the Ambassador on Extraordinary Mission in Constantinople (Hohenlohe-Langenburg), Erzurum,

http://www.armenocide.net/armenocide/armgende.nsf/$$AllDocs-en/1915-08-05-DE-002?OpenDocument

Greeks

While the Armenian population of Erzurum province was deported to the south since spring and especially since June 1915, the province near the border was a deportation destination for Greek Orthodox Christians since 1914. On 14 May 1914 the minister of the interior, Talat, ordered the deportation of the rumlar from Western Anatolia to the East: “For political reasons, it is urgent that the Greek inhabitants of the Asia Minor coast be made to evacuate their villages and resettle in the administrational districts of Erzurum and Chaldia. Should they refuse to relocate to these places, you are requested to verbally instruct our Muslim brothers to force the Greeks into expatriation at their own initiative, by committing all sorts of violent acts against them. In this case, do not forget to obtain signed declarations from those to be displaced that they are leaving their homes at their own initiative.”[24]

This instruction is confirmed by an article in Le Temps of 24 June 1914: “Turkish authorities are forcing the locals to sign declarations that they have willingly abandoned their homes and that nothing untoward has occurred in their villages…. Many dead bodies have been incinerated to conceal any traces of the crimes committed”.[25]

In his memoirs a Greek Orthodox physician recalled his experience in the province of Erzurum: “On the way from Erzincan to Erzurum in early May 1915, close to the road to Kara Su (Euphrates) and near Sansha I came across the bodies of five Greek soldiers who had been savagely murdered and slaughtered on the mountains because they dared offer some bread to the unfortunate Armenians who were being taken from one area to the other. I choose to mention only the bodies of the murdered soldiers and not the hundreds of bodies scattered on the ground along the path that I had been following for days. Those were soldiers from the labor battalions who had died of typhus and were left exposed, to be eaten by wild animals and vultures.

I have to stress that Sansha is the tomb of Greek soldiers who had served in the labor battalions of Samsun, Kerasus, Trebizond, and Erzerum, and died or were slaughtered by the Turks during the retreat.”[26]

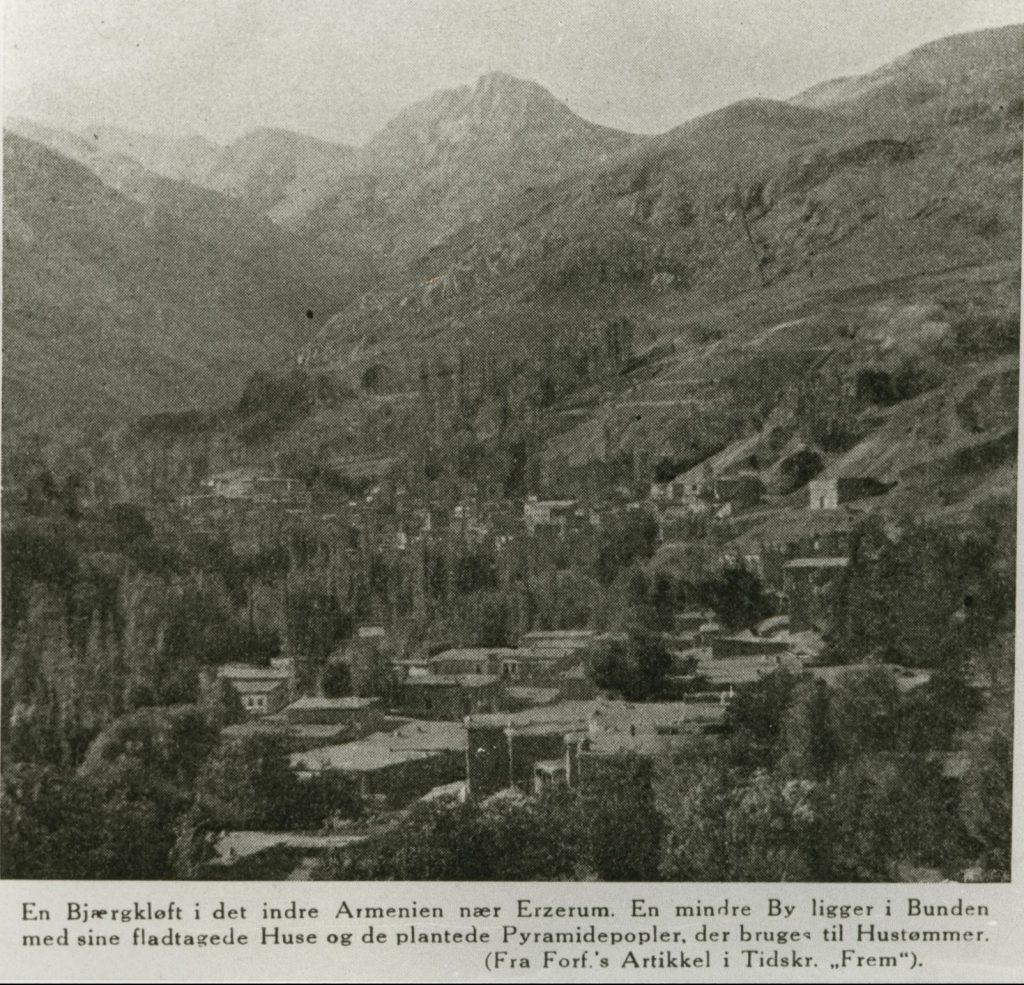

“In April 1915, the inhabitants of Matsouka [Trk.: Maςka] were ordered to abandon their homes and were deported across the Pontic Alps to the interior of Asia Minor, most of them to the Erzurum plateau. The sufferings they underwent in the region’s chill April weather were indescribable. Starvation and infectious diseases would deal the final blow to the Greeks. The freezing cold was the main cause of death among deportees. Confidential decrees and orders rendered Christians outlaws and their life worthless. Yiorgos Laparidis, who survived the hardship of exile to Erzurum, describes in a tragic yet concise manner his personal strife, and that of his fellow villagers:

‘It was 1916. The Russians took Zavera and the Turks ordered that all the men of my village be deported to Erzurum. The weather was chill; it was the middle of January. It was so cold that stones would crack, but we poor men had to go on marching unshod and inadequately clothed. If someone had a pair of peasant shoes on, he was considered very lucky. While we were walking, the gendarmes would hit us with their rifle butts and push us into the river Kanis. We’d become sopping wet. Then they’d lead us out of the river and we would start walking again. Our wet clothes froze on us and the ice could be heard crackling as we moved on.

God alone knows how many people died on the way, or fell ill from the cold, or starved to death! When my group was assembled in Zavera, there were 120 of us. Only 45 made it back…’”[27]

The British diplomat George William Rendel believed “that the destruction and devastation of the numerous villages around Trebizond, which extended into the mountain valleys, occurred during the spring and summer of 1921. When he passed through those places in April 1921, the villages were still full of Greeks, but on his second journey in October 1921, all of them were deserted and ruined. According to his statement, most of the women were naked and had been raped by the Turkish guards. He estimated that approximately one hundred thousand Greeks had been deported to Harput and Erzurum, and noted that a Greek’s life expectancy in the work battalions was less than two months, due to the hard work required and inadequate nourishment.”[28]