Antioch on the Orontes (Ancient Greek: Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou; also Syrian Antioch) was a Hellenistic city on the eastern side of the Orontes River. Its ruins lie near the current city of Antakya. After World War I, Antioch and İskenderun were occupied by France. In 1923, France received the official League of Nations mandate for both cities and Syria. Administered by Damascus, Antioch retained a status as an autonomous area. Nevertheless, Mustafa Kemal’s followers were welcomed with open arms here as well. It is said that it was he who gave the area the name Hatay, in reference to a former Hittite principality.

Toponym

After the Battle of Ipsus in 301 B.C., Seleucus I Nicator won the territory of Syria, and he proceeded to found four ‘sister cities’ in northwestern Syria, one of which was Antioch, a city named in honor of his father Antiochos; according to the Suda, it might be named after his son Antiochos.

Armenian Population

According to the statistics of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 8,532 Armenians in eight localities of the kaza of Antakya, maintaining seven churches, two monasteries and ten schools with an enrolment of 487 pupils.[1]

City of Antiochia – ‘Cradle of Christianity’

Antioch was founded near the end of the fourth century B.C. by Seleucus I Nicator, one of Alexander the Greats’ generals. The city’s geographical, military, and economic location benefited its occupants, particularly such features as the spice trade, the Silk Road, and the Royal Road. Here crossed the trade routes from Aleppo, Mesopotamia and from Palestine to Anatolia and the Mediterranean. The city was connected with the sea via the Orontes (river). Trade with Cyprus is attested in writing and archaeologically. One source of wealth was ivory.

History

Alexander the Great is said to have camped on the site of Antioch and dedicated an altar to Zeus Bottiaeus; it lay in the northwest of the future city. This account is found only in the writings of Libanius, a fourth-century orator from Antioch, and may be legend intended to enhance Antioch’s status. But the story is not unlikely in itself.

After Alexander’s death in 323 B.C., his generals, the Diadochi, divided up the territory he had conquered. The founder of Antiochia, general Seleucus I Nicator is reputed to have built sixteen Antiochs.

Seleucus founded Antioch on a site chosen through ritual means. An eagle, the bird of Zeus, had been given a piece of sacrificial meat and the city was founded on the site to which the eagle carried the offering. Seleucus did this on the 22nd day of the month of Artemísios in the twelfth year of his reign, equivalent to May 300 B.C. Antioch soon rose above Seleucia Pieria to become the Syrian capital.

Antiochia was the capital of the Seleucid Empire until 63 B.C., when the Romans took control, making it the seat of the governor of the province of Syria. From the early fourth century, the city was the seat of the Count of the Orient, head of the regional administration of sixteen provinces. It was also the main center of Hellenistic Judaism at the end of the Second Temple period. Antioch was one of the most important cities in the eastern Mediterranean half of the Roman Empire. It covered almost 1,100 acres (4.5 km2) within the walls of which one quarter was mountain, leaving 750 acres (3.0 km2) about one-fifth the area of Rome within the Aurelian Walls.

The decline of the metropolis began in the 6th century. In 526, the city was severely devastated by the so-called Antioch Earthquake. Only a few years later, the decisive blow came: in 540, the Sassanid king Khosrau I attacked Roman Syria and took Antioch by storm. He deported most of the inhabitants to ‘Chosrauantiochia’ near Ctesiphon and allegedly destroyed the city except for a few buildings. Under Emperor Justinian I (527-565), Antioch was rebuilt with the epithet Theoupolis (‘City of God’), but this settlement covered only part of the former area. Art production, which had flourished until the Persian attack, largely collapsed; apparently no mosaics were made after 540. Nevertheless, Antioch remained important. In 613, a major battle between Eastern Romans and Sassanids occurred near the city, in which the imperial forces were defeated. Probably in 638 Antioch, which had fallen to the Persians in 615 and had not become Roman again until 630, was then conquered by the Arabs.

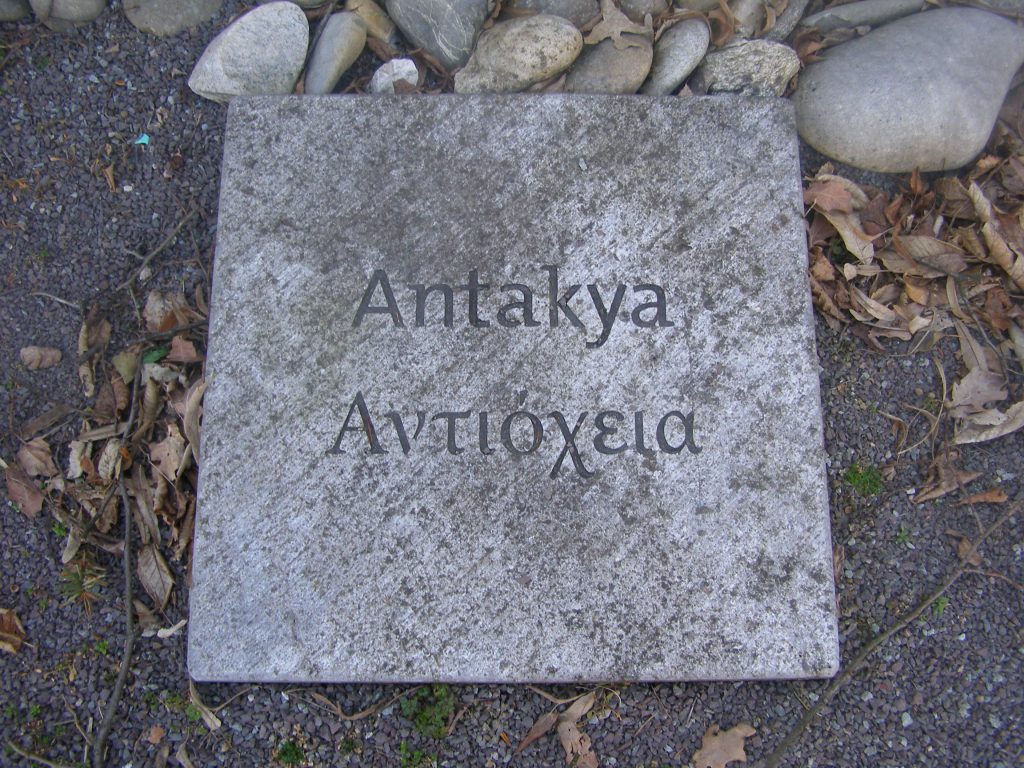

After the Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Manzikert (1071), the Armenian adventurer Vasak seized power. In 1076 or 1080 Byzantine soldiers killed him, and the former Byzantine general Philaretos Brachamios took over. In 1084 the city fell to the Seljuk Sultan Malik Shah I. In June 1098, after a deprived eight-month siege, it was conquered by the Crusaders, who in turn were threatened by the siege of 200,000 soldiers led by Atabeg Kerboga of Mosul only two days after conquering the stockless Antioch. Only after finding the Holy Lance were the 20,000 or so crusaders (including non-combatants) able to rout this formidable superior force on June 28, 1098. Byzantium had not supported the trapped Crusaders, but had stopped its own troops at quite a distance and finally, believing in the imminent defeat of the Crusaders, had them turn back to Byzantium. Therefore, after the Crusaders’ surprising victory, the city was not returned to Byzantium as agreed, but was made the capital of the Principality of Antioch.

During the 12th and 13th centuries Antioch remained in the hands of the Crusaders until it was finally conquered by the Mamluks under Sultan Baibars in 1268. Baibars destroyed the city so badly that it never regained major importance. For the sacking, Baibars had the city gates barred and the entire Christian population of tens of thousands was killed or enslaved, leading to a decline in the price of slaves. Antioch became an insignificant small town. The Greek Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch has resided in Damascus since the end of the 14th century. In 1517, the city became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Christianity

Antiochia was called ‘the cradle of Christianity’ as a result of its longevity and the pivotal role that it played in the emergence of both Hellenistic Judaism and early Christianity. The Christian New Testament asserts that the name ‘Christian’ first emerged in Antiochia.

Antioch was a chief center of early Christianity during Roman times. The city had a large population of Jewish origin in a quarter called the Kerateion, and so attracted the earliest missionaries. Evangelized, among others, by Peter himself, according to the tradition upon which the Patriarch of Antioch still rests its claim for primacy, and certainly later by Barnabas and Paul. Its converts were the first to be called Christians. This is not to be confused with Antioch in Pisidia, to which Barnabas and Paul later travelled.

Surrounding the city were a number of Greek, Syriac, Armenian, and Latin monasteries. Between 252 and 300 A.D., ten assemblies of the church were held at Antioch and it became the seat of one of the five original patriarchates, along with Constantinople, Jerusalem, Alexandria, and Rome (see Pentarchy).

The Maronite Catholic Church’s patriarch is called the Patriarch of Antioch and all the East. He currently resides in Bkerke – Lebanon. The Maronites continue the Antiochene liturgical tradition and the use of the Syrian-Aramaic (Syro-Aramaic or Western Aramaic) language in their liturgies. One of the canonical Eastern Orthodox churches is still called the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, although it moved its headquarters from Antioch to Damascus, Syria, several centuries ago (see list of Patriarchs of Antioch), and its prime bishop retains the title ‘Patriarch of Antioch’.

Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and All the East, is an Oriental Orthodox Church with autocephalous patriarchate founded by Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the 1st century, according to its tradition. The Syriac Orthodox Church is part of Oriental Orthodoxy, a distinct communion of churches claiming to continue the patristic and Apostolic Christology before the schism following the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

Population

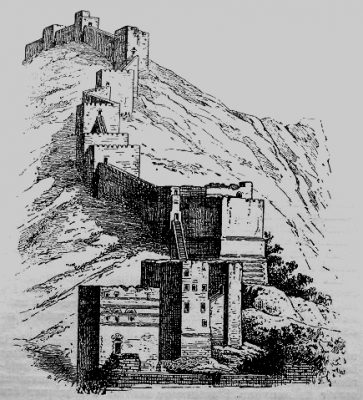

During the late Hellenistic period and Early Roman period, Antioch’s population reached its peak of over 500,000 inhabitants (estimates generally are 200,000–250,000) and was the third largest city in the Empire after Rome and Alexandria.[2] The city may have had up to 250,000 people during Augustan times. John Chrysostom writes that when Ignatius of Antioch was bishop in the city, the dêmos, probably meaning the number of free adult men and women without counting children and slaves, numbered 200,000. In a letter written in 363, Libanius says the city contains 150,000 anthrôpoi, a word which would ordinarily mean all human beings of any age, sex, or social status, seemingly indicating a decline in the population since the 1st Century. Chrysostom also says in one of his homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, which were delivered between 386 and 393, that in his own time there were 100,000 Christians in Antioch, a figure which may refer to orthodox Christians who belonged to the Great Church as opposed to members of other groups such as Arians and Apollinarians, or to all Christians of any persuasion.

Antiochia declined to relative insignificance during the Middle Ages because of warfare, repeated earthquakes, and a change in trade routes, which no longer passed through Antioch from the far east following the Mongol invasions and conquests.

Notable people

- Arcadius of Antioch (2nd century B.C.): Greek grammarian

John Chrysostom (Byzantine mosaic, Haghia Sophia) - Aulus Licinius Archias (Ἀρχίας; fl. c. 120 – 61 B.C.), Greco-Syrian poet

- Asclepiades of Antioch, Patriarch of Antioch

- Saint Barnabas, one of the prominent Christian disciples in Jerusalem

- Saint Domnius, Bishop of Salona and patron saint of Split

- George of Antioch, the first to hold the office of ammiratus ammiratorum

- Ignatius of Antioch, Patriarch of Antioch

- John Malalas ( Ἰωάννης Μαλάλας – Iōánnēs Malálas; c. 491 – 578): Byzantine chronicler

- John Chrysostom (Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; c. 347 – 14 September 407): Patriarch of Constantinople; important Early Church Father

- Libanius, 4th century A.D., pagan sophist and confidant of Emperor Julian

- Saint Luke, 1st century A.D., Christian evangelist and author of the Gospel of St. Luke and Acts of the Apostles

- Severus of Antioch, was the Patriarch of Antioch, and the head of the Syriac Orthodox Church

- Tiberius Claudius Pompeianus, Roman politician and general

- Saint Maron, Patriarch of the Maronite Church

Attempted Destruction and Successful Self-Defense of Musa Ler / Musadağ

Although the Armenians in the coastal areas of the Aleppo vilayet were initially to have been exempted from deportation, the authorities ultimately issued an order to deport them as well in late July 1915. On 1 August 1915 the Armenian notables of Antakya were arrested.[3]

Already on 9 May 1915 regular troops and gendarmerie had invested the Armenian villages of Musadağ to conduct searches of schools, churches, and homes, after Muslim villagers of the area had obviously informed on their Armenian neighbors.[4]

“A witness and participant of the events that occurred in Musadağ, Dikran Andreasian, a Protestant minister in Zeitun, who came from Yoğunoluk, reports that when the order to deport the villagers from the region was issued on 30 July, many, such as Harutiun Nokhudian, a Protestant minister from Bitias, thought that it would be ‘folly’ to resist it. Thus 332 families from Kebiusia/Körderesi (pop. 240), Yoğunoluk (2), Hacihabibi (80), and Bitias (10) submitted to the order and were conducted somewhat later to Antakya, where they were subsequently deported to Der Zor on the route running parallel to the Euphrates. What the minister from Zeitun does not say, however, is that after finally returning to his native village, Yoğunoluk, on 25 July, thanks to the intercession of American missionaries from Marash, he informed his compatriots of the way that Zeitun had been emptied of its population. The information apparently had a crucial impact on the Armenian village leaders’ decision to withdraw to positions on the mountain with the villagers who chose to go with them – the 868 families or around 4,200 people who took to the maquis beginning on 31 July. (…) After the week’s reprieve that they had been granted by the authorities had expired, 200 regular soldiers launched a first attack on them on 8 August. Although the assault was pursued for xis hours, the attackers were unable to break the Armenians’ defense. Two thousand troops were sent to the area from Antioch over the next few days, setting up a bivouac on the mountain 600 meters below the Armenian lines. The defense committee immediately decided to launch a surprise attack during the night, which threw the soldiers into a panic and caused heavy loss of life. (…)

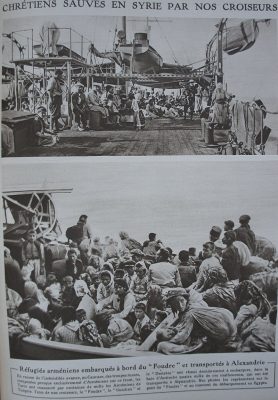

At this point, the authorities adopted a new tactics. According to Andreasian, around 15,000 men from the surrounding villages were armed and positioned the mountainous area defended by the Armenians, creating a hermetic siege. Then, on Tuesday, 10 August, after the Armenian positions had been pounded by artillery, a second assault was launched. It was at this point, Andreasian reports, that the besieged Armenians considered the possibility of opening a path on which they could make their way toward the coast and escape by sea. Before they had been completely surrounded they had sent a messenger to the outside world, bearing an appeal written in English by Andreasian, which declared as a result of the ‘policy of annihilation which the Turks are applying to our nation,’ the inhabitants of Musadağ had withdrawn into the mountains, where they were under siege. Two immense white flags, one bearing the words ‘Christians in distress: rescue’ and another bearing a red cross, were fabricated and hoisted on the mountaintop to make them visible from the sea below. On the morning of 10 September, a French battleship, the Guichen, sighted this appeal for help from the besieged Armenians of Musadagh, who sent a delegate to the ship. In the next 24 hours three other cruisers, including the Jeanne-d’Arc, arrived in the area and set about bringing more than 4,000 villagers on board. It took no fewer than 36 hours to complete the operation, and another two days to make the journey to Port Said, Egypt.”[5]