Toponym

During its long history, the name of the kaza’s administrative seat changed frequently. In Byzantine and Armenian sources, the place name Sevaverek – Սեւավերակ (‘Black Ruins’) is used, which refers to the color of the local stones. The Sasanids named the city Surk after its red soil. The Persians used the name Serrek (‘ser’ – ‘head’). The Arabs called the town as-Suwaidāʾ (the name of a Kurdish clan mentioned in the Sharafname), which means ‘the black’ and ‘love’. The Turkish version Siverek is documented since 1530; another Turkish toponym is Kankalesi (‘Blood Fortress).

Christian Population

The 1914 census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople mentions an Armenian population of 9,275 in eight localities of the kaza Siverek, maintaining eight churches and three schools for 250 students. The principal town of the kaza, also named Siverek, had an Armenian population of 5,450 on the eve of the First World War.[1]

The administrative seat of Siverek had a Syriac population of 1,200, and there was a rural population of 6,550 Syriacs in 32 villages.[2]

Localities inhabited by Armenians were:

Adro (Hadro), Azro, Bushak, Gyungyormez, Yerkush, Khrrbek’, Khorzon, Khuri, Garaburj (Karabrjik), Hoshin, Mzre, Nisibin (Nrzip, Mtsbin), Chat’akh, Severak town, Srmakh, Veranshehir.[3]

Սեվերեկ գավառակ

Ադրո (Հադրո), Ազրո, Բուչակ, Գյունգյորմեզ, Երկուշ, Խըրբեք, Խորզոն, Խուրի, Կարաբուրջ (Կարաբրջիկ), Հոշին, Մզրե, Նիսիբին (Նըզիպ, Մծբին), Չաթախ, Սևերեկ քաղաք, Սըմախ, Վերանշեհիր գյուղաքաղաք։

Notable Personalities

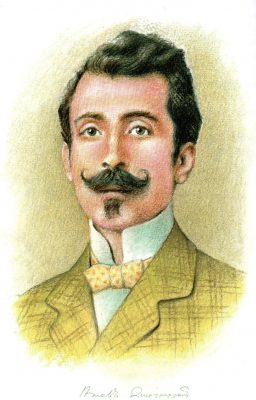

Ռուբէն Զարդարեան – Ruben Zardarian

Ruben Zardarian (Ṙowbēn Zardarean; West Armenian pronunciation: Rupen Zartarian) was born in 1874 in the small town of Severek (Trk.: Siverek) near the provincial capital of Diyarbekir, but after his parents moved, he lived from the age of two in the provincial capital of Kharberd (Trk.: Harput, now Elazıg), where he attended first an Armenian and then an American school before entering the private educational institution of his literary idol, Tlkatintsi (T’lkatinc’i; Թլկատինցի; Western Armenian pronunciation: Tlgadintsi; i.e. Hovhannes Harutiunian, 1860-20 June 1915). Like Tlkatintsi, Zardarian, who had been publishing since the age of eleven, was considered a representative of Western Armenian village literature and, like his mentor, became a victim of the 1915 eliticide.

From 1892 to 1903, Zardarian worked at the Central Armenian School of Mezire (Mamuret ül-Aziz), where he taught Armenian, French, Armenian literature and history. Arrested for his political involvement in the social revolutionary party Dashnaktsutiun in 1903, Zardarian spent a year in prison. In 1904, he went to Smyrna to take charge of an Armenian school there, but local authorities prevented him from doing so. Instead, he was allowed to go to Manisa, where he headed an Armenian school for a short time, but official harassment set in there as well, driving him into exile. From 1905 to 1908 he stayed with his family in the Bulgarian city of Plovdiv (Greek Philippopolis, Turkish Filibe), editing the Armenian journal Razmik. Like numerous other exiled Ottomans, Zardarian returned to his homeland after the Young Turk revolution in 1908. He worked in Constantinople as a teacher, from December 1908 at the Armenian journal Jamanak (‘Time’), and from 1909 as editor of the main party organ of the Dashnaktsutiun, the daily Armenian journal Azatamart (Ազատամարտ – ‘Freedom Fighter’).

In addition to his intensive journalistic activity, Zardarian emerged as a poet, prose writer (novellas, fairy tales, fables), author of literary articles, and translator into Armenian of Maxim Gorky, Vladimir Korolenko, Émile Verhaeren, Victor Hugo, Anatole France, Percy Shelley, Oscar Wilde, and Selma Lagerlöf, among others.

Although since 1902 the leadership of the Dashnaktsutiun had been in pact with the Ottoman constitutionalists, who had also been forced into exile, and in particular with the oppositional Committee for Unity and Progress, the members and leaders of Dashnaktsutiun were among those severely persecuted in the course of the eliticide of 1915. The newspaper Azatamart had already been banned by the decision of a military tribunal on 18 March 1915. The entire editorial staff, including Zardarian, were among the first to be arrested in Constantinople around 24 April 1915; the editorial offices were sealed.

Deported to Ayaş (Ankara province) as a political activist, incarcerated and sent on under guard via Konya and Aleppo toward Diyarbekir on 5 May 1915, Zardarian was to stand trial before a military court. On the way, however, brigands led by Lieutenants Halim and Nazım and Major Sirozlu Çerkez Ahmet (‘Ahmed the Circassian’) ambushed him and murdered Zardarian near a place called Karacaören on 15 August 1915.

Ruben Zardarian: The Gampr, a Wolfhound

He is a huge, magnificent Gampr, invigorated both by the climate of the plains and the mountains where he grew up. He moves gracefully and majestically, always remaining calm when pursued by the pack of dwarfed, mangy and dirty city dogs. To both flanks hang luxuriant curls that testify to his noble ancestry, while the loss of hair on his back betrays his old age and the infertility it has caused. The broad and strong chest with protruding curls of hair gives the animal an extraordinary beauty, in stark contrast to the pitiful pack born and raised in the dirt and dung of the streets, which chase and yap at him. But why are they yapping at him? This is the passion of the street, which oozes through the pavement as mud. That is the unworthiness of the inferior and pathetic instinct, which feels challenged by the disproportionate opposition and revolts against it, running and howling. They and their good-for-nothing descendants still flock from all directions, who have been idly sleeping in front of the butcher shops and bakeries. And they still call to their aid those heroes who have positioned themselves around the slaughterhouse. The older ones show off, threatening with a rough voice, the younger ones threaten conceitedly, as ridiculous as this seems, and the little ones, encouraged by the boldness of the older ones, spout curses with their childishly immature voices as always aimlessly and without thinking.

Thus, they run panting after the Gampr, who goes on his way unperturbed and self-confident. It sounds many-voiced and many-tongued, there is a loud shouting, but all this does not diminish his calm and majesty, which is the real cause of the anger and excitement. He just keeps walking, rarely turning his head, effectively keeping the overly forward and brash at bay with a warning. Those who nevertheless dare to come a little closer, and whose breath he feels on his sinuous tail, he throws back into the vile, filthy stream of his pursuers with a faint snarl pressed through his teeth and a monotonously threatening growl. The pack of haughty rulers of the rubble heaps and streets is pathetic and disgraceful in their common incompetent pursuits.

What noble haughtiness of an animal, an aged Gampr, who unfortunately already limps on one front paw, which impairs his proud gait. Nevertheless, the injury does not harm his physical dignity, but still highlights his undoubted strength and highhearted nature.

But how did this aberration come about? What drove him from the mountains to the plains and then to the city? What fate has brought him to the strange environment where he experiences the company of his disease-infected, hungry brothers, and where he and the offspring he has begotten vegetate in the rain, sleep in the mud, unaccustomed to the wretched way of life on the road? Where, without willingness to submit, he is unable to obtain even a crumb and would have to die of hunger. So, what was the cause of this animal’s sad adaptation, so similar to human fate and life’s demands? If he himself cannot relate his situation, his lame paw tells us the whole truth.

*

It is known that he belonged to a nomadic community. Born of the blood of powerful parents, as a Gampr and descendant of a Gampr, he spent his childhood in the perilous mountains. Already in the first days of his life, deep in his soul awoke the hatred for the wolf and the willingness to sacrifice for the herd. He experienced his mother’s eternal fierce vengefulness when she chased wolves. Her heroic anger, vigor, and bloody battles taught him the necessity of always putting everything on the line to protect the flock entrusted to him, taught him loyalty to his master and sacrifice to the last, and, if necessary, to die covered in blood and with his body torn apart in front of the eyes of the shepherd and the sheep in the pen.

The dawn of his childhood began in this way. After that, miracle after miracle! How happy his Amazonian mother felt when she returned to her puppy with a bloody snout as a victress. Or after that magnificent struggle, when the boy displayed the splendor of his irresistible strength, the first lacerating terrors of his teeth, and the indomitable resistance of his muscles. His mother, resting her head contentedly and carelessly on her paws, slept soundly at night, for the raucous barking of her boy reached into the valleys and ravines and kept away the wolves that frightened in their dens.

The years passed, full of excitement and full of life, without weakness, without rest, without fear. But the cruel master of time, the Satan of aging, came crawling over the rocks, up into those mountains, and found the Gampr as well.

The fur began to fall out of him, the curls lost their luxuriance, the back fur thinned tragically, and in the last struggle one of his paws had been crushed. He suspected that a devastating destruction had begun inside him. The lame leg was a hindrance to his invincible chest, affecting his instinct, his sense of life, and his ever-awake passion, for instead of admiration he now detected pity in the gaze of the shepherd and in his surroundings. Thus, circumstances took a hopeless and unpleasant course, no longer compatible with the rebellious grandeur of his soul. He decided to despise the contempt in order not to submit to an abandonment to which he was never worthy.

Then, limping, with effort and torment, he descended from the mountains to the plains and arrived in the city, in the streets, where the pack of doggies of all shades and shapes yapped at him and tried to pursue him, full of derision for his boldness and strength. Is then the world of these pusillanimous dogs so limited that they raise such a clamor for the sake of a bone? Is a morsel really so valuable in these narrow and smelly alleys that one must even compete with cats for its sake, from which, by the way, the loud-mouthed dog brigade, to which he shows his fangs under his bared lips, hardly differs?

Ignorant pack, be at least once critical of your close environment and show the willingness to dream of something higher than your groveling ordinariness! Try to understand the horizon of a Gampr, so that the light of his magnanimity and honesty may open your eyes and you may realize the depth of your baseness, the wretchedness of your pity? Whom do you persecute and what is the cause of your angry barking? Is it so difficult to behold the splendid figure of a Gampr in all its sublime perfection?

*

He always walks serenely, without haste, without fear, confidently, with contempt for the pack of dogs, leaving behind their deafening clamor, outrageous boasts and threats. The tribunal of the gutter, that is the street philosophy of hungry dogs, neglected young dogs and blind puppies. This is consequently the entire town that is yet to be mobilized.

Run exalted, run with your head held high, you, a Gampr! Remove yourself from this mediocre impudence that is not ashamed to bark at nobility and that howls against dignity. They want to drive you away from these places, shamelessly wagging in front of passers-by and ready to humiliate themselves like that because of a bone.

Run, so that your way may find its end! Because you have come to a wrong place and are in wrong surroundings. Return to the solitude of the plains, to the boundless expanses of the mountains. Do not fear the troubles and storms that rage in the heights. It is better to starve than to beg for a piece of bread from a greedy city dweller, to immerse up to the chest in the mud! It is much better to die of numerous wounds in the unequal fight with a young wolf, than to end your life’s term on a street corner, humiliated in the hour of death.

Destruction

“Severek, the medieval Sevaverag (‘Black Ruins’), was the principal town in the kaza. The town had an Armenian population of 5,450 on the eve of the first World War; this represented more than the half of the total population. Seven other localities in this basically rural district known for its red wine were home to 3,825 Armenians: Karabahçe, Çatak, Mezre, Simag, Harbi, Gori, and Oşin. (…)

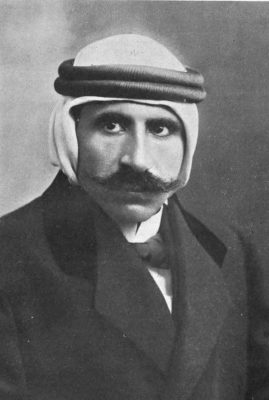

According to the meager sources available to us, the house searches and elimination of the men took place in May 1915, followed by the deportation of the women and children. A few survivors reached Urfa or Aleppo. The only credible eyewitness account, by Faiz el-Güseyin [Faiz Bey el-Ghusein], an Arab Bedouin who had been parliamentary deputy and a kaymakam, describes Severek and the vicinity shortly after the elimination of the Armenian population (probably in July). El-Güseyin observes that initially a multitude of corpses littered the road between Urfa and Severek, above all those of women and children. The Armenian bodies that he saw the next day on the road to Dyarbekir were probably not those of natives of Severek, but of people deported from regions to the north.”

Excerpted from: Raymond Kévorkian: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 366f.

“The [Syriac] men and priests were killed and the women raped. The bishop Athanasios Danho was 79 years old. He was jailed, tortured, and then crushed to death under stones.”

Excerpted from: Gaunt, David: Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I. Piscataway: Gorgias Press, 2006, p. 261