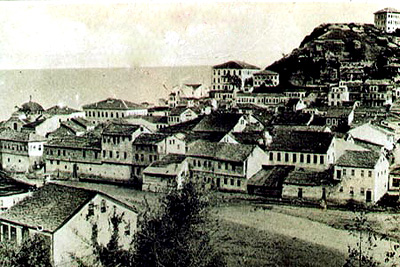

“Many houses which represent Greek and Ottoman architecture typical of the Black Sea coast still exist. Many old buildings offer scope for restoration. Close to the town lie the ruins of an old monastery. The natural landscape of Inepolis is one of greenery and natural beauty. There are also many beaches in the vicinity.“[1]

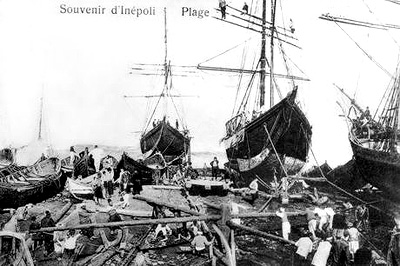

Visiting in August 1893, British parliamentarian and explorer H. F. B. Lynch noted how little then remained of the old Greek cities of the ‘Argonautic shore’. At ‘Ineboli’ he reports finding a fragment of ancient sculpted marble near the shore, and describes the town as ”a line of white-faced houses with roofs of red tiles [that] nestles beneath the mountain wall. The Greeks live on one side, the Turks on the other: and the intelligent man to whom you naturally address yourself is an Armenian in European dress.”[2] Lynch also reports that “carriageable roads” had recently been constructed inland to Kastamonu.

The port exported mohair, animal hide, wool, and hemp. They imported mainly manufactured products.

Administration

By 1834, İnebolu was considered a sub-district of today’s city of Küre (approx. 30 km inland), but it became a district in its own right in 1867. In the late 19th and early 20th century, İnebolu was part of the Kastamonu Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire.

Toponym

İnebolu was initially called Aboniteichos (Άβώνου τειχος – Avonon Teikhos). The name was changed to Ionopolis in the middle of the 2nd century C.E. Over time, Ionopolis metamorphosed to Inepolis, and then to İnebolu, though sometimes spelled “Ineboli” by foreign travellers.

From the former name Ionopolis derives the theory that İnebolu was founded by Ionians.

Population

The sancak of Inebolu on the Black Sea coast had four Armenian parishes: Inebolu (pop. 1,497), Taşköprü (pop. 1,497), Eskiatfa (pop. 434), and, in the southwestern part of the sancak, Tosya (pop. 130).[3] Düzce, “northwest of Bolu, had an Armenian population of 392, Deverek [Devrek] , 50 kilometers further east, had an Armenian population of 670; Zonguldak, on the coast, had a community with 512 members; finally, Bartin [Bartın] had a community of 420.”[4]

Town of Inebolu / Ινέπολη – Inepolis / Inebolu / Bolu

Population

Before the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), Inepolis had a population of 5,765 of which 3,000 were Greeks[5] and 1,497 were Armenians[6]. The Christian communities “profited from the city’s geographical location on the main road through Asia Minor to engage in very profitable trade.”[7]

As a result of the exchange of populations most of these Greeks were expelled to Greece.

There are undated ruins of a Greek-Orthodox monastery, which have been heavily pillaged by artifact-seekers. Only some parts of the walls, large main entrance stairs, the baptismal basin and well remain. Greeks who live in İnebolu celebrate the 15th of August (Dormition of the Mother of God) here by holding a feast.

History

The exact founding date of İnebolu is unknown. At first it belonged to the Roman province Pontus, since Marcus Aurelius, when it was also called Ionopolis, to the province Galatia.

Ionopolis had no connection to the interior in the early period. This connection was only established by the Zarbana (Üzluce) road, 18 km to the west. Ionopolis, like the other Ionian cities, remained under the sovereignty of the Roman-Byzantine Empire after the destruction of the Lydian and later the Persian kingdoms.

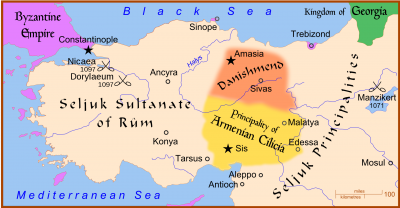

Due to the victory in the Manzikert battle, Inebolu fell to the Seljuk Empire in 1071. After the fall of the Seljuk Empire, the city increasingly deteriorated. Within the borders of Candaroğullari (Isfendiyarids), the Turkish tribal kingdom of the Candar brothers, it was given the present name İnebolu.

İnebolu was incorporated into the present town of Küre (about 30 km inland) in 1413. Fires in 1880 and 1885 led to the total destruction of the Inebolu. The then Sultan Abdülhamit II had a plan drawn up according to which houses and streets were rebuilt in a rectangular pattern. This resulted in the present cityscape with houses made of brick. The then very old road over Küre high above the mountains from İnebolu to Kastamonu, dating from around 1327, was not upgraded until 1907.

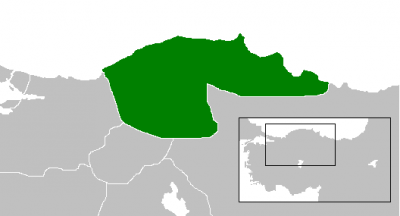

During the Turkish War of Independence, arms and ammunition were transferred to Anatolia through İnebolu. The town was therefore attacked by the Greek fleet in 1921. After the Kemalist victory in the Greek-Turkish war, most of the ethnic Greek residents in the area were forcibly resettled in Greece. Many of these emigrants settled in a neighborhood called Inepolis in the Athenian suburb of Nea Ionia. The formerly predominantly Greek villages in the sancak of Inebolu were given Turkish names. Today, these villages are still known by two names among the population.

Destruction

Deportation and Massacre of Armenians 1915

“The elimination of the men was carried out behind a façade of legal proceedings. A ’commission of inquiry’ headed by someone named Mehmet Ali Bey was created in Bolu. Its leading member was the police chief, Izzet Bey, who was responsible for the house searches and arrests. The court-martial under the presiding judge Sopaci Mehmed was responsible for condemning those indicted. Its activities were overseen by Dr. Ahmed Midhat, chief of police in Constantinople, who had been sent by the CUP to Bolu to supervise the 24 September deportation and massacre of the sancak’s Armenian population, with the help of Suraya Effendi, a member of the district’s general council; Habib Bey, a parliamentary deputy from Bolu, and Ibrahim Bey (who had been implicated in the 1909 Adana massacres) and Tahir Bey, the leader of a squadron of çetes [irregulars] that counted among its ranks, notably, Hafiz Ali, Sarı [‘yellow’, ‘blond’] Mehmed, Postaci Nuri, and Cendarma Kancarci Emin.

An Armenian survivor, held in the prison of Bolu until the end of his trial on 23 January 1916, reports that some of those indicted were accused of being members of the Armenian Benevolent Society and condemned to hard labor for that reason, and that others were condemned to death and executed for reasons just as trivial. (…)

According to another account, the police chief Izzet Bey played a crucial role in concocting the indictments by planting ‘prohibited objects: weapons, bombs, and so forth, and English, French and Russian flags’ in Armenian homes. He is also supposed to have summoned the Armenian notables to the prefecture, where they were arrested and then handed over to the çetes. (…) The same source has it that Mondays were ‘holidays for the Turks, since Monday was hanging day.’ The gallows were erected on the square where the city government was based toward which ‘a crowd overflowing with sinister joy’ streamed. Many children were ‘adopted’ by Turkish families, while young Armenian women were ‘imprisoned in the harems.’”[8]

Deportation of Greeks (June 1916)

“The first community to be expelled was that of Djide [Cide; also Karaağaç]. In June 1916, the inhabitants received the order to assemble at the sea shore and were embarked on sailing vessels and dispatched to Ineboli, without being allowed to take anything with them. The day after the arrival of those expelled from Djide (22 June), an order was given to the inhabitants of Ineboli, to prepare also during the week for their departure.

Ineboli being evacuated as well as the neighbouring communities of Patheri, Atsidono, Karadja, Askordassi. The inhabitants and the sick of Djide, were conducted to Castambol [Kastamonu].

The establishment of Christian refugees at Castambol in no way served the programme of destruction pursued by the Turkish patriots, hence a second deportation, surpassing in brutality the first took place. The refugees were sent to Tatai, Aratch, and Gangrass and thence to the Turkish villages of the neighbourhood and the Moslem borough of Tcherkez [Çerkez, i.e. Çankırı].

The Turks committed great destruction in this region and burnt down the Church at Patheri on the eve of the expulsion from Ineboli and plundered the fine library of the Central School.”[9]

After the World War, in 1921 the Kemalists continued the extermination of the Greek Orthodox population in sancak Inebolu. “According to a comment by a columnist of the Trieste newspaper Nea Imera, the displacement and murder of Greeks aged 16 to 50 started after May 26, 1921, as reprisals for the bombardment of Inepolis by the Greek fleet. Actually, the order to exterminate all Greeks had been given in February 1921. Kemal’s supporters were simply waiting for the appropriate opportunity to justify their crimes.”[10]