Toponym

During the Byzantine era the city of Tokat was known as Evdokiada (Gr: Eυδοκιάδα). This toponym goes back to the daughter Evdokia of its founder, the Byzantine emperor Herakleios (610-641), abbreviated Dokia (Gr: Δόκεια). It was also referred to as Tokation (Grk.: Τοκάτιον). During Ottoman times the name Tokat was the name of the kaza and sancak which the town was situated in.[1]

The kaza was also known as Kazova.

Christian Population

Before the First World War, there lived 17,480 Armenians in 18 localities of the kaza of Tokat. They maintained 17 churches, two monasteries and 11 schools with an enrolment of 1,400 students.[2]

The kaza of Tokat consisted of many Greek villages up until the genocide and subsequent exchange of Populations (1923). The number of (Greek Orthodox?) churches in the kaza is given with 82, the number of schools with 79 (12 of these for girls), with an overall enrolment of 2,878 pupils.[3] Based on a 1911 survey Greek villages in Pontos, Ioannis Sianloglou gave in 1923 the number of Greeks in the Tokat kaza with 10,800, residing in 27 localities with 20 schools, 29 churches and one monastery[4] close to Keksa at a distance of 2 hours by foot from the Tokat city.

City of Tokat

History

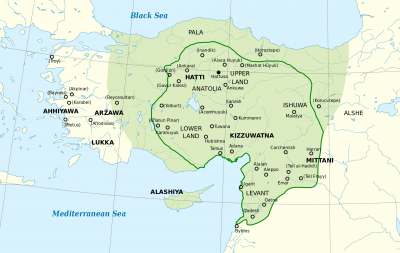

Tokat, the ancient Eudoxia (also called Eudocia, Eudokia, or Evdokia) has a long history, beginning with the Hittites in the 2nd millennium B.C. However, it did not play a major role in ancient times, only its fortress Dazimonitida (Grk.: Δαζιμωνίτιδα) was of importance.

In 190 B.C.Eudoxia entered the kingdom of Lesser Armenia, which later joined the kingdom of Pontos. After the defeat of Mithridates VI Eupator (“good father”; 111-63 B.C.) in the Roman-Pontic War, it was annexed to the Roman Empire. From the end of the 4th century to 1071 Eudoxia was part of Byzantium. In 8th and 9th centuries, the Arabs attacked Eudokia but were unable to capture it.

Around 1021, Seneqerim-Hovhannes Artsruni of Sebaste received the city as a fief of the Byzantine emperor. The Armenian Artsruni had moved westward fleeing the Seljuks. In 1045 Eudoxia passed by marriage to the Armenian Bagratid dynasty. From 1071 to 1175 the Turkmen Danishmend ruled it. From the 11th to the 13th century, trade flourished in Eudoxia. 1174-1307 Eudoxia was ruled by the Seljuk-Turks, in 1307-1398 by the Mongols. Evdokia was annexed to the Ottoman Empire in 1398, and renamed it Tokat. In the 17th century, Evliya Çelebi compared Tokat’s prosperity to Bursa and Aleppo. In the 19th century, Tokat was one of the largest cities in Asian Turkey.

Christian Population

The population of Tokat included a high percentage of Christians until the 20th century. The Armenian Apostolic Church was the majority, with seven congregations and its own archbishop. The archbishop usually resided in the Armenian monastery of Surb Hovakim and Anna outside the city and often served as its abbot.

Armenians played an important role in the economic and cultural life of Tokat. They were engaged in handicrafts (copper and silversmithing, weaving, jewelry, leatherwork, etc.), trade, and gardening.

Evdokia was one of the centers of medieval Armenian writing, where many manuscripts were copied here. The Armenians had two monasteries (St. Hovhannes Voskeberan or Surb Nshan, and Surb Hovakim and Anna), seven churches (St. Trinity, St. Minas, Surb Astvatsatsin, Surb Lusavorich, Surb Karapet, Surb Gevorg, Holy 40 Children), five schools (National, Voskyan, Varduhyan, Holy Trinity and Nersesyan), and three kindergartens. There were theatrical groups (in 1912, under the direction of Daniel Varujan, Hakob Paronian‘s “Honorable Beggars” (1891) was staged). The magazine Yerakhayrik was published in Tokat since 1883, and the half-monthly Iris since 1910; printing houses were operating.

During the Roman-Byzantine reign (First century B.C. – 12th century A.D.), a small number of Greeks settled in Tokat, inhabited by Armenians, and a significant number of Muslims during the subsequent Muslim conquests, especially during the Ottoman rule.

The Greek Orthodox community, which was Turkophone in everyday life, had a church and several schools; the Greek archbishop residing in Tokat held the title of the bishopric of Neocaesarea (now Niksar), which dated back to antiquity. The scholar of Greek linguistics and folklore, Dimosthenis Oeconomidis (1858-1938), stated that prior to WW1, Tokat had 40,000 residents of which only 1,000 were Greeks, 15,000 were Armenians and a small number were Jews.[5] According to Raymond Kévorkian, there lived 11,980 Armenians and about 15,000 Turks in the city of Tokat on the eve of the war.[6]

According to S. Ioannidis Tokat had 18,000 residents, consisting, among others, of 400 houses of Turkophone Greeks, as well as 100 Turkish houses. Ioannidis also mentions that apart from those who openly declared their Christian faith, a further 100 families were cryptochristians (Klosti), practicing their Christianity privately.[7]

In the 19th century, Tokat became a center of Catholicism in the Pontos region. In 1859 the bishopric of Tokat degli Armeni of the Armenian Catholic Church was established, but in 1892 it was united with Sebaste (Sivas) and since then it has been granted only once (1972) as a titular bishopric. The Jesuits, active here from 1881 (nominally until 1926), maintained a college, and the Congregation of the Armenian Sisters of the Immaculate Conception of Mary maintained a convent. The Jesuit Guillaume de Jerphanion, first explorer of cave architecture in Cappadocia, worked in Tokat from 1903-1907 and again in 1926. There was a larger Armenian Protestant community around 1854. American Protestant missions began to appear in 1864.

Notable Armenians

– Apkar (Abgar) Tbir (Dpir) Tokhatetsi (Abgar the Scribe; 1520?–1572?): cleric, colonist, printer and typographer, statesman

– Michael of Tokat (c. 1595-c. 1660): scribe and miniaturist (floruit 1606-1658)

– Vartan (Vardan) Hunanian (1644-1715): Armenian Catholic bishop of Lviv

– Avetik of Tokat (Avetik Tokhatetsi, 1657-1711): Patriarch of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople

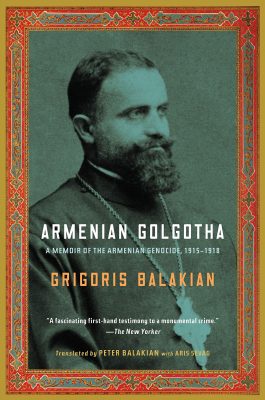

– Grigoris Balakian (Գրիգորիս Պալագեան – Grigoris Palagian; 1875-1934): Armenian bishop; survivor and witness of the Ottoman genocide against the Armenians

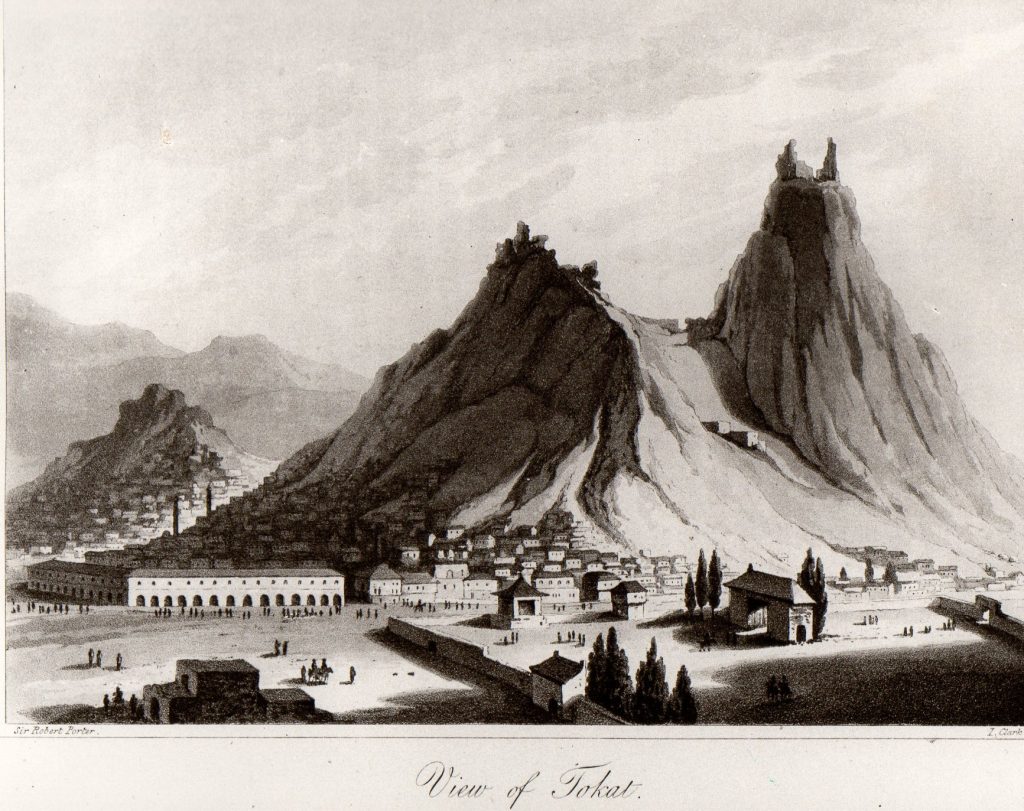

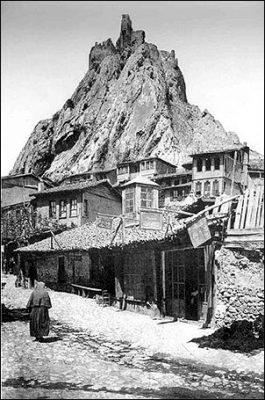

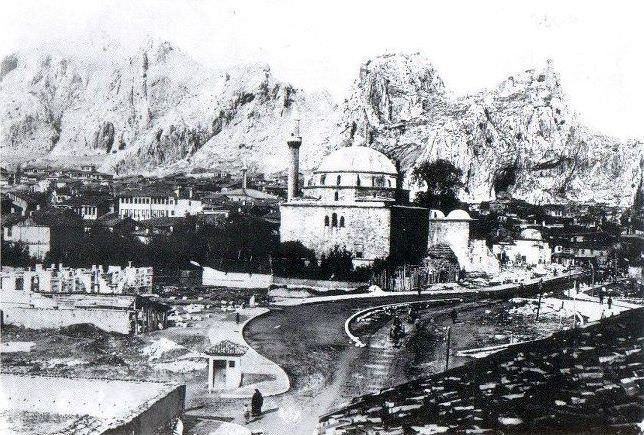

“...the ancient town (Tokat) is located just above modern Tokat and has its citadel preserved in its entirety among inaccessible cliffs. Today’s town is in a valley by the river Iridos (Iris or Yesil Irmak), the banks of which contain remnants of Greek architecture. The ancient fortresses have been saved and are located atop two mountains from which the view of the surrounds is impeccable. The new town can be seen extending from the foot of the mountain. The foundation of Tokat settlement was a result of ancient Comana (Comana Pontica) which is situated to the east and was (settled) no later than the middle of this century (ie. no later than 1850). The Armenians call the town Evdokian or Evdoksian. The town was notorious for its textile industry and its copper manufacturing plants which were reliant on the Kempan Maden mine, a mine which has since been depleted but which in the prior century kept 600 factories in operation.”

Dimosthenis Oeconomidis (Ikonomidis; 1858-1938), quoted from: https://pontosworld.com/index.php/pontus/places/212-tokat-tokat

Destruction

“The most striking event in the months preceding the outbreak of the war was the fire set on 1 May 1914 that ravaged the street where many of Tokat’s businesses were located, Baghdad Cadesi. (…) There is (…) every reason to believe that these events reflected the general strategy adopted by the Ittihad in February 1914 with a view of diminishing the economic importance of the Greeks and Armenians. (…) The situation deteriorated in April 1915, when the CUP sent its parliamentary representatives into the provinces of Asia Minor to preach elimination of the ‘domestic foe’.”[8]

In the beginning of May 1915, Tokat’s four main Armenian political leaders were arrested and executed in the town’s prison. Following a visit by Governor Muammer to Tokat, which took place at the same time, all the Armenian functionaries in the police and gendarmerie were dismissed.

On 18 May 1915, the authorities arrested all the Armenian notables and teachers of Tokat, as well as the adolescents a bit later that day, who were imprisoned in the central food stockhouses and systematically tortured there.

“On Wednesday, 16 June, a new stage opened with the systematic arrest of the men, beginning with Father [Shavarsh] Sahagian. That afternoon, Sahagian was summoned to the konak [administrative seat], where the police chief Mehmed Effendi informed him that he had to go to Sivas immediately to meet with the vali [governor]. He was killed that very evening on the way there, in Kızın Eniş.”[9]

On 17 June 1915, 1,400 men from Tokat, bound together in groups of ten, were escorted in four convoys outside the town in the valleys of Ardova, Ğazova, and Bizeri, and then executed.

On the following day, seventeen clergymen, including the auxiliary bishop Nerses Mgrditchian and Father Andon Seraydarian, were assassinated in the citadel at Tokat. Over the next ten days, males between the ages of fourteen and twenty were executed.

In the end of June 1915, the remaining population, around 9,000 people, was grouped by age and deported accordingly. The Azar han served as the provisional detention center for mature women, who were questioned by police en route, followed by young women, and then the last Armenians who took the Sivas route (via Çiftlik-Yeni Han) to Sarkışla/Maraş, or more frequently to Kangal/Malatya. The operations were overseen by Special Organization bands, notably Salhi Ağa (the local butcher), Çerkez Mirza Bey, Çerkez Osman Bey, Çerkez Mahmud Bey, and Çerkez Elmalızade Haci Effendi.[10]

“Mother! I was called up as a solder…” (Armenian Song)

Mother, mother! I was called up and taken away,

I wasn’t given a rifle, but was enlisted in the labor battalion,

The Tokat village of Yatmish was less than four days distant,

The stones of Yatmish had to be broken down;

The waters of Tokat were so abundant.

Everybody’s hope was to come back,

Days, days, I go in such grievous day,

I go, I go, I go as a soldier,

I go to break stones.”

Quoted from: Svazlian, Verjiné: The Armenian Genocide: Testimonies of eyewitnesssurvivors. Yerevan: “Gitoutyoun” Publishing House of NAS RA, 2011, p. 552