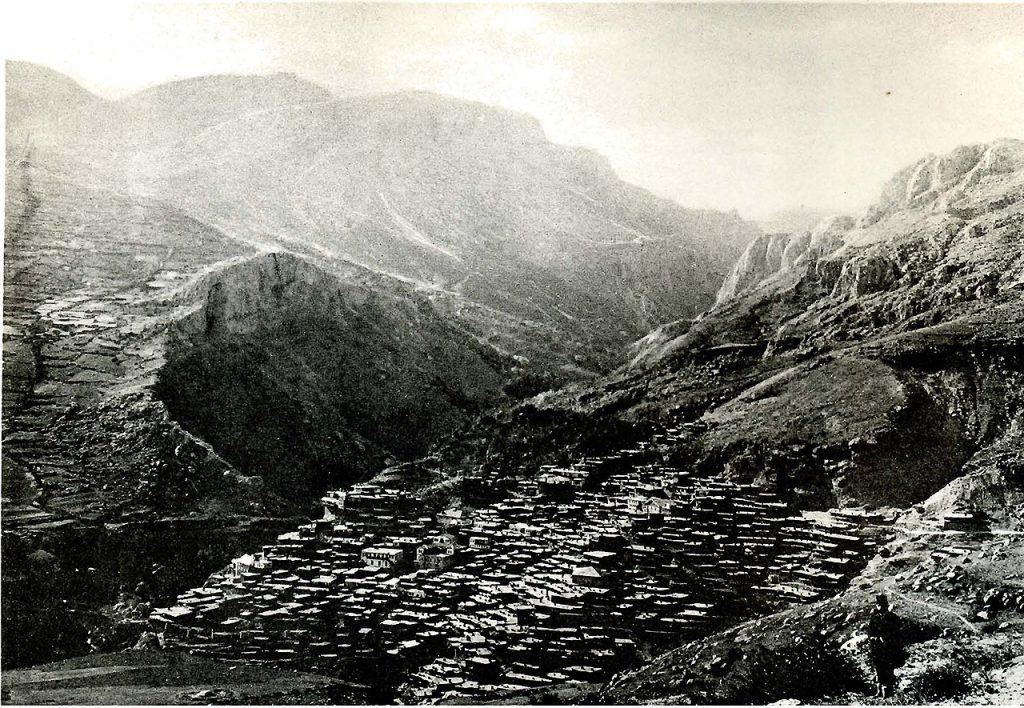

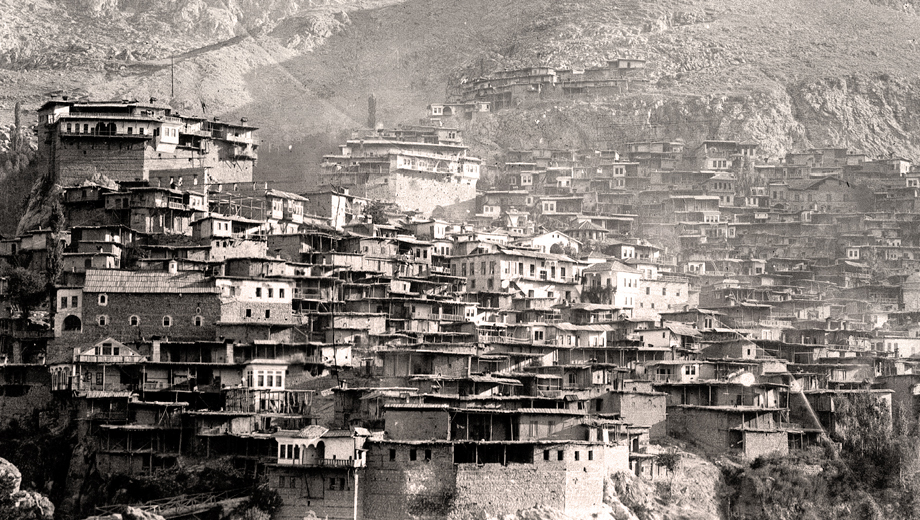

Zeytun is surrounded by mountains, forming a natural barrier around the city and making the town inaccessible to enemies. The tributaries of the Jahan River, which originate from the Tauros mountain range, flow through Zeytun. The rivers are rich in fish (carp, etc.). The climate is temperate, warm and healthy. Fruit trees, olive trees, pomegranate trees, fig trees, grapes, and cereals such as wheat, barley, corn grow. Minerals include iron and silver. There are also mineral waters.

Toponym

The placename derives from Arabic/Turkish ‘zeytun’ (olive tree), which is borrowed from the Armenian word ‘dzetun’. Trees of this fruit grow in abundance around the city and in the warm valleys. The second toponym, Ulnia, derives from the Byzantine settlement of Ulnia in the place of Zeytun. On 8 June 1915, the town was renamed Süleymanlı after an Ottoman military commander Süleyman Bey who was killed fighting Armenian resistance against the Armenian Genocide in the town in 1915. “The decision to rename Zeitun (…) shows the beginnings of the program of Turkifying the Anatolian region by way of the liquidation of its Armenian population and also by changing place names there.” [1]

Armenian Population

According to the census of the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople there lived 22,456 Armenians in 18 localities of the kaza Zeytun. They maintained 14 churches, three monasteries, and 10 schools for 690 pupils.[2]

“They lived in the town of Zeitun and six rural communities. Located on the foot of the southern face of Mt. Berid, the town was built, level after level, on the slopes of two valleys. To the north, on the heights, lay the monastery of the Holy Mother of God. In 1914, the town of Zeitun had a population of 10,600. It was divided into four neighborhoods (located in the two lower quarters) governed by a city council headed by the bishop of the region. It was known for horse-shoeing, stonecutting, and the production of agricultural tools, but its inhabitants also cultivated olive-trees, fruit trees, and a few different types of grain. They also raised horses, cattle, sheep, and goats, and produced brandy, wine, raisins, honey, wool, and leather.

An hour southeast of Zeitun laid the villages of Avakenk, Kalustenk, Hacidere, Avakhal/Mehal, and Alabash (3,200 Armenians). Finally, in the northernmost part of the kaza laid the village of Yavuz (1,100 Armenians).”[3]

History

After the fall of the Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia (1045), seven Armenian families who migrated from the previous Bagratid capital Ani settled in Shehirchok (Շեհիրճոկ), giving it the name ‘Ani-dzor’ (Valley of Ani). The territory entered the Armenian state of Cilicia in 1080-1375. The population increased with Armenians in-migration from Shirak, but mostly from Cilicia, after the fall of the Armenian state of Kilikia (1375). The name of the region and village of Zeytun was mentioned for the first time at the beginning of the 15th century, when the Zülkadir tribe ruled most of Cilicia. From the 15th century to the beginning of the 16th century, it was under the rule of the Zülkadir and the Karamanid tribes. In 1517, Zeytun accepted Ottoman subjection, committing to pay a tax to the Sublime Porte (5000 ghurush).

In 1626-1627, the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV, fearing the movement of the Jalals, in order to win the support by the Armenians of Zeytun, gave them a status of autonomy (firman)[4] in exchange for an annual tribute of only 15,000 kurush (Ottoman gold coin). In the 16-18th centuries, Zeytun was governed by the principle of military democracy. The province was ruled by four princely houses: the Shovroyans, the Yaghubians, the Yenitunians and the Surenians. The four districts of Zeytun were named after these houses, which they owned by hereditary right. Issues related to the entire region were resolved by the princely council, where the right to say the last word was reserved to the senior prince and the archbishop of Zeytun. However, in the second half of the 19th century, the Ottoman rule over Zeytun was nominal, the Armenians of the kaza defended their semi-independent status, and forbade foreigners to cross their borders. In 1865, direct Ottoman government was established in Zeytun and the governmental rights were abolished. Despite the proclamation issued once by Murad IV, the surrounding Turks, especially the governors of Maraş, continuously tried to conquer and subjugate the province. Such attempts were made in 1780, 1808, 1819, 1829, 1835, but they always ended with the victory of the Armenian mountaineers. Rebellious, triumphant, and brave, the people of Zeytun have for centuries defended their privileged position with the force of arms, often refusing to pay taxes.

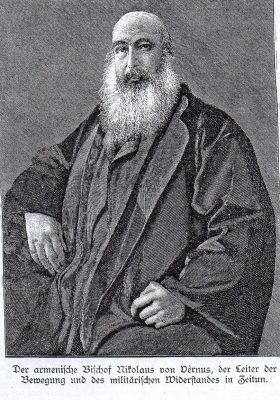

The Ottoman government did not come to terms with the semi-independent state of Zeytun, and in the 1860s,it undertook to completely abolish the autonomy of the province. In 1862, the victorious Zeytun rebellion broke out. Despite this, Sultan Abdül Mejid succeeded in abolishing the semi-independence of the province, and the inhabitants were subjected to heavy taxation. In response to the violence of the Turks, a new rebellion broke out in 1878, led by Prince Papik of the Yenitunian dynasty. The fights that lasted for almost two years ended with mutual concessions. The community of Zeytun continued its existence, but the Ottoman government built a barracks on the hill overlooking the city and began to follow the mountaineers. In 1895-1896, the people of Zeytun made a self-sacrificing resistance to the Hamidian massacrers. The self-defense battles were led by 75-year-old Prince Ghazar Shovroian and Aghasi Honchakian. Those fights ended with the intervention by the consuls of the European states. In 1780-1909, Zeytun faced the Ottoman troops 41 times, writing heroic pages in the history of the Armenian liberation struggle. In March 1915, the Armenians of Zeytun were forcibly deported and driven to the Deir-el-Zor desert, and the city burned down. Some of the inhabitants were massacred, the survivors were deported to different countries.

Destruction

The Armenian population of the mountain town of Zeytun, famous for its spirit of defiance, was one of the first victims of the genocide against the Ottoman Armenians. All the elements of the state crime that was subsequently carried out nationwide were tried out on them as if in a test run. This also included the eliticide: „The mutesarif [of Maraş], Ali Haydar Pasha, went to Zeitun in person, accompanied by an army brigade. He summoned the Armenian notables there, who were arrested and tortured in the barracks located in the city’s heights. Officially, it was a question of bringing them to confess that they were preparing a rebellion, and also of forcing them to give up their arms. A total of 42 notables, notably the charismatic leader of the inhabitants of Zeitun, Nazaret Yenitunian, were taken to Marash in chains. Most of them were poisoned or killed in some other way in the following weeks. In other words, the authorities were utilized a method in Zeitun that would be brought to bear on other regions the following year.”[5]

On April 8, 1915, the first of three deportation convoys departed. Some Armenians returned to Zeytun during the occupation of Cilicia by the French army from 1918 to 1921. However, when the region was ceded back to Turkey, the Armenians were forced to flee once again.

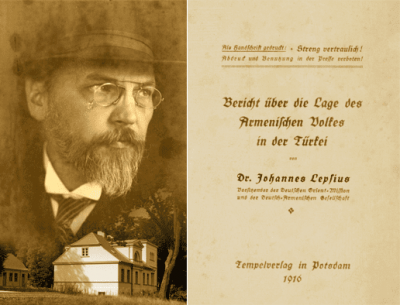

Johannes Lepsius: Zeitun

“Zeitun, 50 kilometers north of Marash, is located in a high valley of the Taurus. The town’s strong Armenian population had a degree of independence and self-government until the [18]70s, much like the Kurdish Ashirets (tribes) in Kurdistan to this day. At the time of the massacres under Abdul Hamid, the inhabitants of Zeitun managed to resist the surrounding Turks and hold their own against Turkish troops until the consuls of the Powers intervened and provided the inhabitants of Zeitun with an amnesty. This success of the resistance of the Zeitun population meant that they were spared from the general massacre of 1895/96, but directed the lasting suspicion of the authorities against them. Since the outbreak of the European War, there seems to have been a desire on the part of the authorities to exploit the mountain nest of Zeitun as soon as the opportunity arose.

“Zeitun, 50 kilometers north of Marash, is located in a high valley of the Taurus. The town’s strong Armenian population had a degree of independence and self-government until the [18]70s, much like the Kurdish Ashirets (tribes) in Kurdistan to this day. At the time of the massacres under Abdul Hamid, the inhabitants of Zeitun managed to resist the surrounding Turks and hold their own against Turkish troops until the consuls of the Powers intervened and provided the inhabitants of Zeitun with an amnesty. This success of the resistance of the Zeitun population meant that they were spared from the general massacre of 1895/96, but directed the lasting suspicion of the authorities against them. Since the outbreak of the European War, there seems to have been a desire on the part of the authorities to exploit the mountain nest of Zeitun as soon as the opportunity arose.

During the general mobilization in August 1914, the Armenians of Zeitun who were fit for military service were conscripted without any resistance. However, until October, when Nazaret Çavuş, the head of the Zeitun municipality, came to Marash with an escort letter from the Turkish kaymakam (district administrator) to arrange official matters, he was thrown into prison despite being escorted freely, where he was tortured and died. Nevertheless, the people of Zeitun remained calm. It seemed, however, that the authorities sought cause to intervene. Zaptiehs (Turkish gendarmes), who were on security duty in the city, harassed the inhabitants, entered houses, looted magazines, maltreated harmless people and dishonored women. The inhabitants of Zeitun got the impression that something was being done against them, but they stayed calm. In December 1914, the delivery of all weapons was ordered, which took place without incident. If at any time later the Armenians of Zeitun had thought of resisting, they would not have been able to do so after the disarmament. The whole winter remained quiet in Zeitun. Then, in the spring, Turkish gendarmes disgraced Armenian girls and a brawl broke out in which about 20 Armenian hotheads participated and several were killed on both sides. The Armenians involved, among whom were some deserters, fled to escape punishment to a monastery three quarters of an hour north of the city, where they barricaded themselves.

To the astonishment and horror of the inhabitants of Zeitun, a large military contingent – it was said that there were four to six thousand soldiers – arrived from Aleppo to Zeitun soon after, at the beginning of March 1915. The military deployment against Zeitun aroused the greatest concern throughout Cilicia. (…)

The Vali (governor) Jelal Bey was not assigned to the investigation, but was dismissed because he did not comply with the orders of the central government regarding the treatment of the Armenians.

Zeitun was surrounded. At the sight of the numerous troops, white flags were raised in the city as a sign that no resistance was being thought of. The refugees in the monastery defended themselves for a whole day and, being in good cover and shooting well, killed a larger number of soldiers, while they themselves had only one wounded. The people of Zeitun specifically asked the commander not to let the fugitives escape, lest they be held liable for their misdeeds. Nevertheless, the fugitives managed to escape, as the guarding during the night was insufficient. The next morning at about 9 o’clock, before their escape was known in the city, the commander summoned 300 notables of the city to a meeting in the camp. Since until then they had lived on good terms with the authorities, those summoned appeared without suspicion. Most of them came in their usual working clothes, only some of them had some money with them and were dressed better. Some of them came in from their herds in the mountains. When they arrived at the Turkish camp, they were not a little surprised to hear that they would not be allowed to return to the city and would be shipped out without further ado. They were not even allowed to provide themselves with the necessities for the journey. Some were still allowed to have wagons brought, but most went on foot. Where to, they did not know.

Then the deportation of the entire Armenian population of Zeitun, about 20,000 souls, took place. The city has four quarters. One by one they were taken away, the women and children mostly separated from the men. Only six Armenians had to stay behind, one from each craft.

The deportation lasted for weeks. In the second half of May Zeitun was completely emptied. Of the inhabitants of Zeitun, six to eight thousand were sent to the swamp districts of Karabunar [Karapınar, Konya province] and Suleimanie between Konya and Eregli [Ereğli, Konya province], 15 to 16 thousand to Deir-ez-Zor on the Euphrates into the Mesopotamian steppes. Endless caravans passed through Marash, Adana and Aleppo. The nutrition was insufficient. Nothing was done for their settlement or even accommodation at the destination of their shipment.”

Excerpted from: Lepsius, Johannes: Der Todesgang des Armenischen Volkes; Bericht über das Schicksal des Armenischen Volkes in der Türkei während des Weltkrieges. Potsdam: Missionsbuchhandlung und Verlag, 1930; Reprint: Heidelberg 1980, p. 4-7

Testimonies of an Eyewitness

An eyewitness who saw the deportees from Zeytun pass through in Marash describes a convoy of deportees in a letter dated 10 May 1915:

“I saw them on the way. An endless procession, accompanied by gendarmes who drove them forward with sticks. Half dressed, exhausted, they dragged themselves and picked themselves up again when the Zaptieh approached with a raised stick. Others were pushed forward like donkeys. I saw a young woman sink down; the zaptieh gave her two or three blows, and she got up with difficulty. In front of her walked her husband with a two- or three-year-old child in his arms. A little farther on an old woman stumbled and fell in the dirt. The gendarme poked her two or three times with his truncheon. She did not move. Then he kicked her two or three times, but she remained motionless. Finally, the Turk kicked her so hard that she rolled into the ditch. I hope she was dead. The people who arrived here in the city have not eaten for two days. The Turks did not allow them to take anything except a blanket, a mule, a goat. Everything they had they sold for next to nothing, a goat for 6 piasters (90 pennies), a mule for half a pound to buy bread for it. Those who still had money and could buy bread shared it with the poor until their money ran out. Most of it had already been stolen from them on the way. A young woman, who had become a mother only eight days before, had her donkey taken away on the first night of the journey. The deportees were forced to leave all their belongings in Zeitun, so that the Muhadjirs (immigrants), Muhammedan Bosniaks, who are to be settled in their place, can dispose of them immediately. There must be about 20,000 to 30,000 Turks in Zeitun now. (…)

The city and the villages around Zeitun are completely emptied. Of the 25,000 or so who were deported, 15 to 16,000 were directed to Aleppo, but they are to go on from there to the Arabian desert. Do they want to let them die of hunger there? Those who have come through here are going to the Vilayet Konia [Konya]. There are deserts there, too. For two or three weeks they remained at the end of the Anatolian railroad near Bozanti [Pozantı, Adana province], because the railroad was busy with troop transports. When those shipped arrived in Konia, they had not eaten for three days. The Greeks and Armenians of the town joined forces to support them with money and food, but the Vali of Konia refused to give the shipped people anything: ‘They would have everything they need’. So they remained without food for another three days. Only then did the Vali lift his ban and, under the supervision of the Zaptiehs, food was allowed to be distributed to them. My correspondent told me that on the way from Konia to Karabunar [Karapınar], a young Armenian woman threw her newborn child, whom she could no longer feed, into a well. Another mother would have thrown her child out of the train through the window.”

On May 21, 1915, the same eyewitness wrote:

“The third and last train of people from Zeitun passed through our town [Maraş], on May 13 at about 7 o’clock, and I was able to speak to some of them in the khan [caravanseray] where they were staying. They were all on foot and had not eaten for two days, during which it rained heavily. I saw a pitiful little girl who had been marching barefoot for more than a week and was dressed only in a tattered apron. She was shivering from cold and hunger, and her bones were literally sticking out of her body. A dozen children had to lie down on the road because they could not march any further. Did they die of hunger? Probably. But we will never learn about it. I also saw two poor old women from Zeitun. They belonged to a rich family, but they were not allowed to take anything with them except the clothes they wore. They managed to hide five or six gold pieces in their wigs. Unfortunately, on the march, the sun reflected in the metal, and the gleam attracted the eyes of a Zaptieh. He wasted no time in taking out the gold pieces and made short work of them, tearing off their wigs.

Yet another characteristic case I saw with my eyes. A formerly rich citizen of Zeitun carried two goats as debris of his belongings. A gendarme comes and grabs the two reins. The Armenian asks him to leave them to him, adding that he already has nothing to live on. Instead of any reply, the Turk beats him crookedly and lamely until he rolls in the dust and the dust turns into bloody mud. Then he gave the Armenian another kick and left with the two goats. Two other Turks watched this spectacle without batting an eye. None of them thought of interfering.”

About the fate of the exiles in Karabunar [Karapınar, Konya province], a letter dated May 14, 1915, states:

“A letter I received from Karabunar, the truth of which cannot be doubted since the author is known to me, assures that of the Armenians who have been sent in the number of six to eight thousand from Zeitun to Karabunar, one of the most unhealthy places in the vilayet, 150 to 200 die of starvation there every day. Malaria wreaks havoc among them due to the complete lack of food and shelter. What cruel irony that the government pretends to send them to establish a colony there; they have neither plow nor seed, neither bread nor shelter, for they have been sent with completely empty hands.”

Excerpted from: Lepsius, Johannes: Der Todesgang des Armenischen Volkes; Bericht über das Schicksal des Armenischen Volkes in der Türkei während des Weltkrieges. Potsdam: Missionsbuchhandlung und Verlag, 1930; Reprint: Heidelberg 1980, p. 7-11