In 1867, the Eyalet Kurdi (Kurdistan) was dissolved and replaced by the Diyarbekir Vilayet. Cezire (Jezire) became the seat of a kaza in the sancak of Mardin. The kaza was subdivided into nine nahiyes, and possessed 210 villages.

Toponym

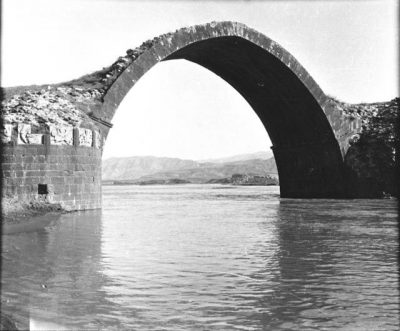

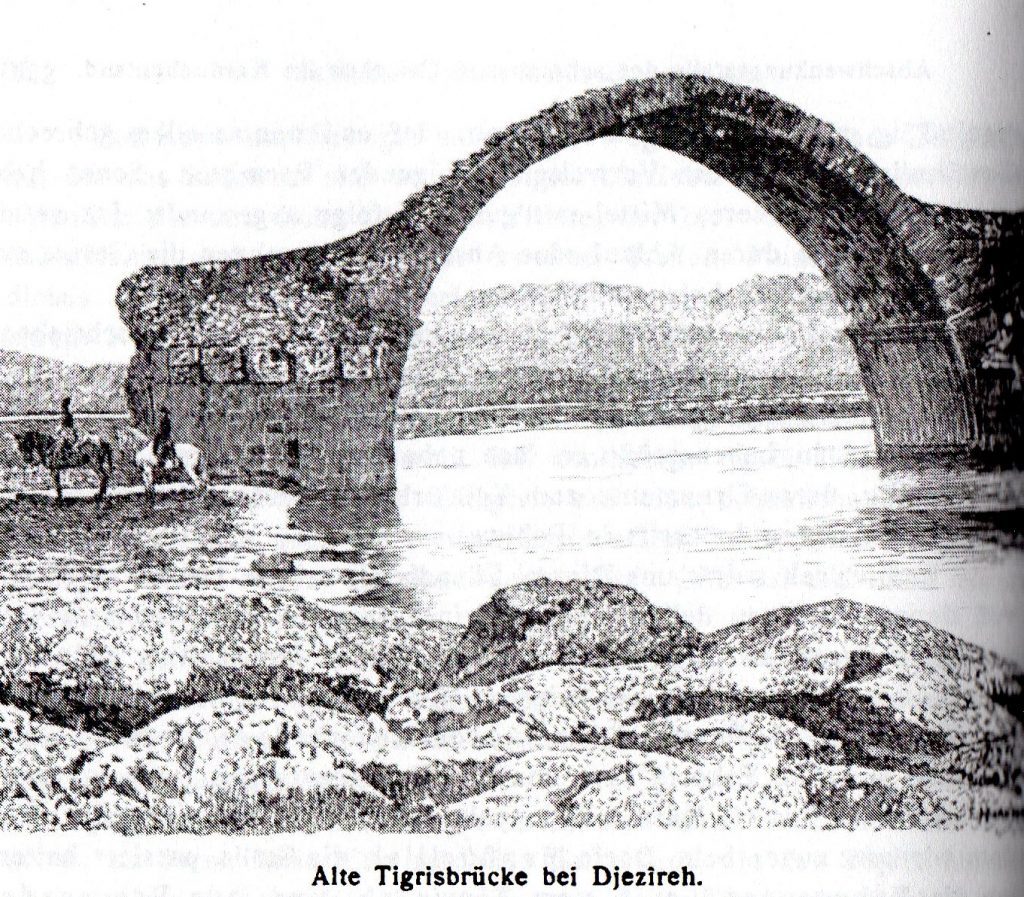

Cizre is derived from the Arabic word Jazira (Arabic جزيرة ‘island’), because here the Tigris river washes around the city like an island during high water. The various names for the city of Cizre descend from the original Arabic name Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar (‘island of the son of Umar’). The alternative Arabic toponym Madinat al-Jazira translates to ‘the island city’.

The ancient Aramaic name of the city was Gazarta d’ Kardū; later Syriac toponyms Gāzartā d’Beṯ Zabdaï (‘island of Zabdicene’) and Gziro (ܓܙܝܼܪܵܐ). Under the Persians Cizre was called Gazarta. Also the fortress Bāzabdā, known from the campaigns of Shapur II, was equated with Cizre. The Abbasids renamed the city after its governor Omar in Jazirat-ibn ʿUmar (Ottoman toponym: Cezire-i İbn-i Ömer). Among the Kurdish princes, the city was called Cizîra Botan.

Population

The French geographer Vital Cuinet estimated the population of Cizre in 1891 to be about 10,000, half of which were Muslims (including over 2,000 Kurds); the other half consisted of 4,750 Armenians (2,500 Armenian Apostolic Christians, 1,250 Catholics, 1,000 Protestants), 250 Catholic Chaldeans and 100 Syriac Orthodox.[1]

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople there lived 4,281 Armenians in 12 localities of the kaza Cizre, maintaining one church and five schools with 500 pupils.[2] The Armenian French scholar Raymond Kévorkian noted that in “the easternmost kaza of the vilayet of Dyarbekir, there was a higher concentration of Armenians than in the rest of the sancak [Mardin]. Besides the 2,716 Armenian living in Cezire and 11 villages nearby, 1,565 Armenian nomads, Kurdified Christians, roamed through the kaza.”[3]

In 1850, the Diocese of Gazarta of the Church of the East had 23 villages, 23 churches, 16 priests, and 220 families, whereas the Chaldean diocese of Gazarta had 7 villages, 6 churches, 5 priests, and 179 families; of these, 60 Chaldean Catholic families lived in the administrative seat of Cizre; they were served by one church and one priest.

The Chaldean Catholic Church expanded considerably in the second half of the 19th century, and consequently its diocese of Gazarta grew to 20 villages, 15 priests, and 7,000 adherents in 1867. Afterwards it decreased to 5,200 adherents, with 17 churches and 14 priests, in 1896, but recovered by 1913 to 6400 adherents in 17 villages, with 11 churches and 17 priests.

In 1918, it was reported Kurds made up the majority of the city of Cizre, with approximately 500 Chaldeans and 960 Syriacs.

History

Cizre is identified as the location of Ad flumen Tigrim, a river crossing depicted on the Tabula Peutingeriana, a Roman 4th/5th century map. The river crossing lay at the end of a Roman road that connected it with Nusaybin, and was part of the region of Zabdicene.

Cizre was probably the center of the Iron Age kingdom of Kumme, a buffer state between Assyria and Urartu. In the middle ages Cizre belonged to different empires like the Kurdish Marwanids and Ayyubids, and the Oghuz Turkic Zengids. From the 16th century Cizre was part of the Ottoman Empire.

Medieval Islamic scholars recorded competing theories of the founder of the city. al-Harawi noted in Ziyarat that it was believed that Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar was the second city founded by Noah after the Great Flood. This belief rests on the identification of nearby Mount Judi as the apobaterion (place of descent) of Noah’s Ark. Shahanshah Ardashir I of Iran (180-242) was also considered a potential founder. In Wafayāt al-Aʿyān, Ibn Khallikan reported that Yusuf ibn Umar al-Thaqafi (d. 744) was considered by some to be responsible for the city’s foundation, whilst he argued that Abd al-Aziz ibn Umar was the founder and namesake of Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar.

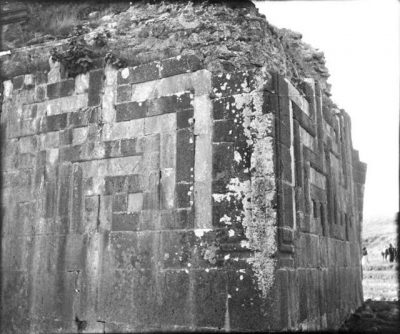

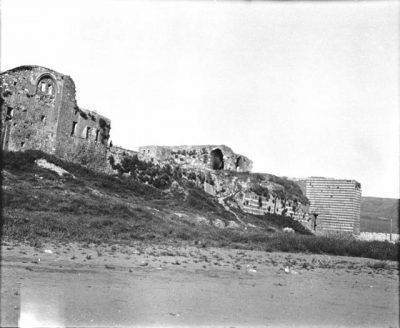

The city was fortified in the 10th century at the latest. In the same century, Ibn Hawqal in Surat al-Ard described Jazirat as an entrepôt engaged in trade with the Eastern Roman Empire, Armenia, and the districts of Mayyafariqin, Arzen, and Mosul.

Turkmen nomads arrived in the vicinity of Cizre in the summer of 1042, and carried out raids in Diyarbekir and upper Mesopotamia. The Marwanid emirate became a vassal of the Seljuk Sultan Tughril in 1056.

In the summer of 1083, the former Marwanid vizier Fakhr al-Dawla ibn Jahir persuaded the Seljuk Sultan Malikshah to send him with an army against the Marwanid emirate, and eventually Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar, the last remaining stronghold, was captured in 1085. Although the Marwanid emirate was severely reduced, its final emir Nasir al-Dawla Mansur was permitted to continue to rule Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar under the Seljuk Sultanate from 1085 onwards.

The city came under Safavid suzerainty in the first decade of the 16th century, but after the Ottoman victory at the battle of Chaldiran over Shah Ismail I in 1514, Sultan Selim I sent Idris Bitlisi to the city and he successfully convinced the emir of Bo(h)tan to submit to the Ottoman Empire. The emirate of Bo(h)tan was incorporated into the empire as a hükûmet (autonomous territory), and was assigned to the eyalet (province) of Diyarbekir upon its formation in 1515. Christian families from Erbil found refuge and settled in Jazirat in 1566.

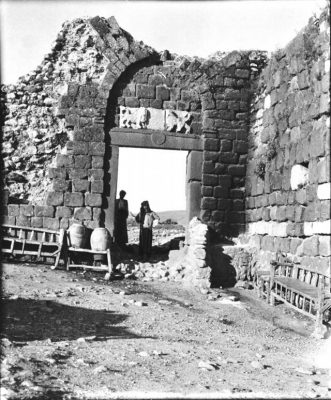

From the 15th to the 19th century, Jazirat, or Jezire was the seat of the Kurdish Principality of Bo(h)tan, which at times was a vassal of various empires. The Kurdish family of Azizan ruled there, whose last ruler was Bedir Khan (Bedirxan) Beg, who reportedly established a munitions and arms factory at the city.

Ecclestical History

East Syriac

Gazarta (Aramaic for Jezire) was a prominent ecclestical and spiritual center of the East Syriac Church. At the city’s foundation in the early 9th century, it was included in the diocese of Qardu, a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Nisibin in the Church of the East (also called Nestorian Church). In c. 900, the diocese of Bezabde was moved and renamed to Gazarta (Jazirat Ibn ʿUmar), and partially assumed the territory of the diocese of Qardu, which was also moved and renamed to its new seat Tamanon, having previously been based at Penek. Tamanon declined and at some point after the mention of its last bishop in 1265, its diocese was subsumed into the diocese of Gazarta. Gazarta was a prominent center of manuscript production, and most surviving east Syriac manuscripts from the late 16th century were copied there.

The Catholic Church of Mosul, later known as the Chaldean Catholic Church, split from the Church of the East in the Schism of 1552, and its inaugural patriarch Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa appointed Abdisho as archbishop of Gazarta in 1553.

West Syriac

Syriac Orthodox

The Syriac Orthodox diocese of Gazarta was established in 864, and is first mentioned under the authority of the maphrian in the tenure of the maphrian Dionysius I Moses (r. 1112–1142).

There was a Syriac Orthodox church of Mar Behnam at Gazarta in 1748, in which year Gregorius Tuma, Syriac Orthodox Archbishop of Jerusalem, was buried there. There were 19 villages in the Syriac Orthodox diocese of Azakh and Gazarta in 1915, “along with the town of Jezireh and the village of Azakh itself”.[11]

Syriac Catholic

The Syriac Catholic diocese of Gazarta was established in 1863, and endured until its suppression in 1957.

Destruction

In 1915, amidst the ongoing genocide against Armenians and Syriacs perpetrated by the Ottoman government and local Kurds, Aziz Feyzi and Zülfü Bey carried out preparations to destroy the Christian population of Cizre on orders from Mehmet Reşit, vali (governor) of Diyarbekir. From 29 April to 12 May, the officials toured the district and incited the Kurds against the Christians. Halil Sâmi, kaymakam of Cizre since 31 March 1913, was replaced by Kemal Bey on 2 May 1915 due to his refusal to support the plans for genocide. Julius Behnam, Syriac Orthodox Archbishop of Gazarta, fled to Azakh upon hearing of the commencement of massacres in the province in July.

According to the Swedish historian and genocide scholar David Gaunt, the secular leader of Cizre’s Christian community, Gabro Khaddo, “attempted to appease the Ottoman authorities and collaborated to a great extent. He collected the sum of 1,500 gold coins and presented it to Osman Effendi in return for a promise of protection. Gabro Khaddo was instrumented in stopping attempts to form a self-defense unit and visited the neighboring villages giving assurances that they need not fear aggression. This attempt at appeasement ended in catastrophe.

In the short term, Gabro Khaddo’s policy seemed successful, and Jezire alone in the Tur Abdin and Bohtan region survived the early summer intact. Probably it had the support of local authorities, although documentary evidence is lacking. However, very large massacres took place here in August and September 1915. Among those killed were many non-residents, since the town became a staging point for the deportees trickling through from Van and Bitlis. Two groups of Al-Khamsin militia, led by Muhammed Resul and Haji ‘Abdo, who had come from Mardin, organized a full massacre on August 24, 1915. All of the adult men, including secular and religious leaders, were killed at a place known as Chamme Sus on the banks of the Tigris River.”[4]

Christians in rural areas of the district were massacred over several days from 8 August onwards, and several Jacobite and 15 Chaldean Catholic villages were destroyed.

“The massacre of the inhabitants of the rural areas began on 8 August and went on for the next several days. Few survived it. (…) The Orthodox and Catholic Syriac bishops were murdered (…) . On the next day, all the Armenian men and a number of Orthodox and Catholic Syriacs were arrested, tortured and killed. In this tribal region, life revolved around weapons, and the authorities had always to take the power of the local tribes into account. Here more than elsewhere, what temporary witnesses describe as ‘primitive populations’ engaged in limitless violence barely tempered by religious considerations, at the instigation of the authorities and with ‘the participation of the regular army’. On the outskirts of the town, the throats of the Christian men were slit with knives as if in a ritual of sacrifice, and their bodies thrown into the Tigris. In their turn, the women and children were deported on keleks [rafts] toward Mosul on 1 September. The luckiest were abducted by Kurds; the others were drowned.”[5]

After the massacres, eleven churches and three chapels were confiscated. 200 Armenian labor-soldiers from Erzurum were exterminated near Cizre by order of General Halil Kut and in his presence on 22 September 1915.

“On August 24 Muslim militiamen dealt with Cizre’s 2,000 Christian inhabitants, most of them Assyrians. Before then, the Christian communities had managed to buy off local powerbrokers. But, when the time came, the adult males were taken and murdered on the banks of the Tigris. The women and children were taken to a Dominican monastery and an Assyrian church, where they were robbed and raped. Some were then taken away by Muslims; the rest were murdered.”[6]

“The Ambassador on Extraordinary Mission in Constantinople (Hohenlohe-Langenburg) to the Imperial Foreign Office

Telegraphic report, No. 560

Pera, September 11, 1915

The consulate administrator Holstein telegraphs under the 9th of the month from Mosul, that according to information by Turkish troops and confirmed from another side, who passed through Mosul on their march from Djeziré to Baghdad, about a week before, gangs of Kurds, who had been recruited for this purpose by Fetki Bey, a deputy of Diarbekir, massacred the entire Christian population of the city of Djeziré (Vilayet Diarbekir) with the connivance of the local authorities and the participation of the military.”[7]

At the Paris Peace Conference (1919), the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate assessed the number of destroyed villages in the kaza Cizre at 26 and the number of massacred Syriac Orthodox Christians at 7,510[8], including 8 clergymen. According to the Chaldean Patriarch, the losses in his diocese were 5,000 of the faithful as well as the bishop and ten priests.[9] In total, 35 Syriac villages in the vicinity of Cizre and 13 churches and convents were destroyed during the genocide.[10]