Toponym and Administration

The village was first mentioned in writing in 1254 as Dâvâlı. Today’s Deverek was formed by uniting the villages of Develi (also Develu), Everek and Fenese and was declared a county in 1860.

Population

“Five hours southwest of Kayseri, on the southern slope of Mt. Argus, there was still in the early twentieth century a little cluster of 17 localities inhabited by 19,841 Armenians. The principal town of the kaza of Everek/Develi, Everek-Fenese, was in fact an agglomeration of two villages that had merged over the years. There were 8,305 Armenians there in 1914, including the nearby hamlet of Hibe. In the modern period, the neighboring village of Develu, the seat of the kaymakam, was also incorporated into the Armenian agglomeration around Everek. At the time, the agglomeration had four quarters: 1) Everek Ermeni [‘Armenian Everek’] (1,000 Armenian households), 2) Everek Islam or Develu (120 Turkish households); 3) Fenese (700 Armenian households); and 4) Aykostan (120 Greek households).

On the eve of the war, the town was thriving, thanks to the production of wine and liqueurs and also to its silkworm production, which provided the raw material or the local silk manufactories. An American orphanage, opened in 1910 for Armenian children whose parents had been massacred the year before in Cilicia, was closed in summer 1914 on orders from the authorities. Çomaklu, which lay 90 minutes from Everek in the foothills of Mt. Argus, was home to 1,679 Armenians in 1914, farmers or artisans from Cilicia. A short distance south of Çomaklu, the village Incesu had a Turkish-speaking Armenian population of 1,202. Only 273 Armenians lived in Gömedi, located at the southeast. Another 1,115 Turkish-speaking Armenians from Cilica lived in Cücün. (…)

In 1914, the town of Tomarza, in the easternmost part of the kaza of Everek, still constituted an altogether singular case because of its social structure and autonomous mode of functioning. 4,388 Armenian inhabitants lived in four neighborhoods that had been ruled since the twelfth or thirteenth century by four hereditary ‘princely’ families: the Dedeyans, Kalayjians, Maghakians, and Tamuzians. There were also seven Armenian villages in the environs of Tomarza: Söyüdlu (pop. 481), Çayrioluk (pop. 100), Tashkhan [Taşhan] (pop. 750), Yenice (pop. 473), Yağdıburun (pop. 227), Karacıyoren (pop. 275), Musahacılı (pop. 173), and Sazak (pop. 400).”[1]

Town of Tomarza

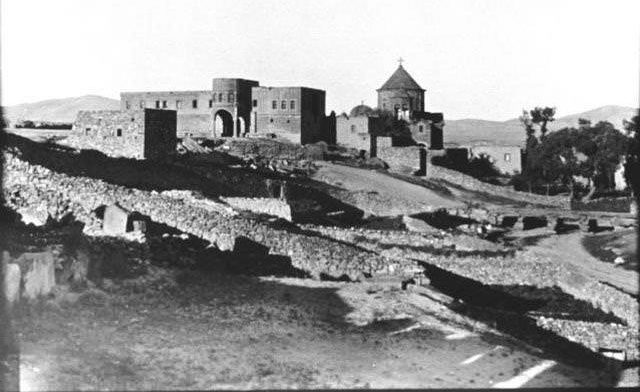

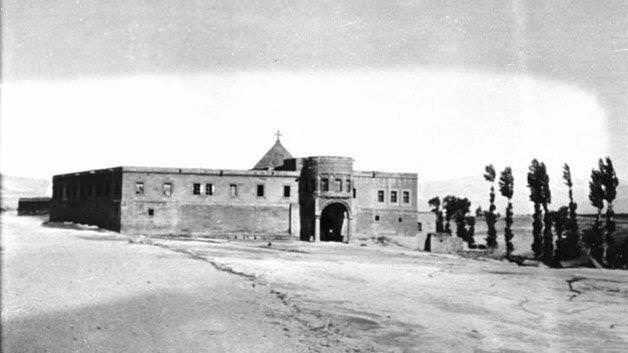

The desolate area “in the no man’s land between Byzantium and the Arabs” was settled with compatriots by the Armenian-Byzantine commander Melias in the early 10th century and elevated to a Syriac Orthodox metropolis in 954/957. In 1065 Emperor Constantinos X Dukas (Doukas) gave the place to the exiled King Gagik of Kars. From 1065 to 1069, the Armenian Catholicos Gregory II resided here. At the end of the 19th century, out of 980 households, Tomarza still had 38 Turkish and few Greek houses, the remaining houses were inhabited by Armenians. In the village existed Surb Poghos and Petros churches, in the eastern part the Surb Astvadzadzin (Holy Mother of God) monastery with ancient Christian church building (Panagia), 6th c. An Armenian bishopric and monastery existed until World War 1.[2]

Toros Madaghjian (1890-1989) wrote the history of his native town in a book called Memories of Tomarza (1959, Armenian). It was later translated into English and published on Amazon. Toros survived the genocide and settled in Racine, Wisconsin where many of his descendants now live.

School Education

„In Everek, up until the 1840’s teachers used to give classes in small schools and rooms in the church premises. In 1864 the idea of having a school building was already developed. For the construction of the building, the Tbrotsaser [Dprotsaser – ‘Schoolloving’] Association raises 30 thousand kurush. In 1870, the Everek Armenian craftsmen in Istanbul’s Chatal Han, send a young teacher with the name of Vramshabuh, from Istanbul to Everek. Although Vramshabuh’s task period remained short, it was a turnin g point in the education history of Everek.

In the 1872-1873 educational year, one boys’ and one girls’, two schools were in operation in Everek, with total of 300 students. The annual budget of 540 kurush was financed by the Tbrotsaser Association. A native of Everek, Parsegh Vartukyan, who had went abroad for his education, came back to his hometown and started teaching. A graduate from the Oxford University, Vartukyan was advocating modern education, but the elite in Everek was conservative. (…) After two years Vartukyan left Everek, and elite’s candidate Garabet Lachikian became the principle of the school.

To improve the deteriorated condition of the schools under Garabet Lachikian, Everek Armenians called upon Mergeryos Atamyan to come from Talas in 1879. After Atamyan, Sarkis Melegyan arrived in Everek, his hometown. Melegyan was going to stay in Everek, taking up several positions for 35 years, by that bringing stability to the Everek educational life.

By early 1880’s, when education was undergoing modernization, Chatal Han’s Everek Armenian craftsmen appealed to the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate for a teacher to be sent to Everek. With the advice of the Patriarchate, Yervant Yergatyan Efendi is sent to Everek in 1883.

Everek Armenians constructed the Surp Toros Church of Everek between 1894 and 1897 (Fatih Mosque today). After one year a building in front of the church is allocated for the schools. Garabet Kalaydjyan became the principle of the schools in 1898. Garabet Hodja takes upon uniting students coming from different classes under one roof.

Although the higher income families are not very welcoming to this approach, Garabet Hodja is able to overcome the challenges. In 1901, in the Everek schools 290 boys and 150 girls were enrolled. With 9 teachers, the annual budget was 1000 kurush, of which 550 was financed by Mesropyan Association founded by Everek Armenians living in Istanbul, the remaining being financed locally. Because of their connection with the Mesropyan Association, the schools in Everek were collectively called the Mesropyan School of Everek.

Other than the Mesropyan, an Armenian Protestant girls’ school also operated in Everek, with 60 students.

In Fenese, in 1885, a building was built next to the Surp Hagop Chapel to serve as a kindergarten. Facing the Surp Toros Church of Fenese, the institution later on grew and united with the boys’ and girls’ schools of Fenese. This united institution was supported by the Rupinian Association of Fenese Armenians in Istanbul. In 1901, the Rupinian School, as it became to be known, had 7 teachers, 290 boy students and 130 girl students. The 1000 kurush budget’s financing was split by half between the Fenese Surp Toros Church and the Rupinian Association.

Overall, there were 61 Armenian and 48 Greek schools in [the sancak of] Kayseri.”

Further Information :

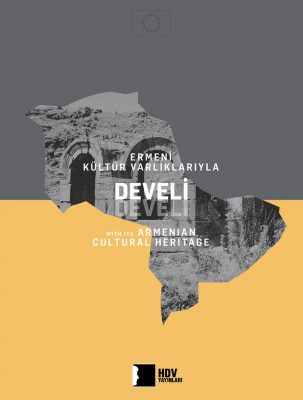

Develi with its Armenian Cultural Heritage: Edited by Vahakn Keshishian, Koray Löker, Mehmet Polatel (Turkish, English). Translation: Sevan Değirmenciyan, Yağmur Ertekin, Betül Kadıoğlu,  Nazife Kosukoğlu, Zeynep Oğuz. Sept. 2018, 143 p.

Nazife Kosukoğlu, Zeynep Oğuz. Sept. 2018, 143 p.

This book reveals the cultural plurality of Develi by tracing the Armenian’s community’s cultural heritage and history. Located in the foothills of Mount Erciyes, home of the two Armenian villages Everek and Fenese, Develi’s historic importance can only be grasped within a multicultural context.

The content of the book is formed by research carried out by the Hrant Dink Foundation between 2016 and 2018. Trying to have a holistic view, the editors put together the knowledge they gathered during the two periods of fieldwork with Develi natives in Istanbul and abroad, and research on the literature, especially from Armenian sources.

After almost three years of research, this book presents the several hundred years’ changing history and the 2018 situation of Develi’s Armenian life and cultural heritage.

| Please click here to download the book. |

Destruction

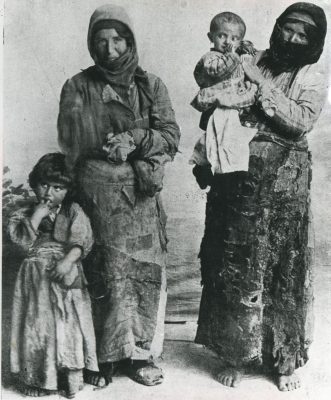

“In March 1915, [the kaymakam] Salik Zeki began by arresting certain local notables, especially political activists. He accused the notables of Incesu of ‘fomenting disorder’ and proceeded to arrest the village headman and the village priest, who were tortured in order to make them ‘reveal’ the names of the ‘troublemakers’. Around mid-May, Zeki went to the village in person, accompanied by a brigade of gendarmes. The priest and his family were murdered, followed by the occupants of the other houses. Their bodies were then loaded onto carts and used to stage a spectacle in the vicinity: rifles and boxes of cartridges that had been ripped open were arranged around the bodies as proof that the gendarmes had eliminated a band of Armenian rebels. Upon returning to Everek, Salih Zeki informed his hierarchy that he had to put down a revolt of Armenians in Incesu, setting up a commission of inquiry and drawing up a report. He then proceeded to systematically arrest the men and confiscate weapons. Imprisoned in the konak and tortured, some of the men died, while others were dispatched to Kayseri and ‘judged’ before the court-martial. While some were condemned to death and hanged with their compatriots in Kayseri, others were ‘deported to Diyarbekir’ – that is, slaughtered by their guards after having been put on the road. Two groups of condemned men were thus murdered on the very day they set out (…).

In the course of July, Zeki ordered the deportation of the kaza’s rural population, arranging for the convoys to take mountainous routes so as to force them to abandon the goods that they had taken with them on setting out. In Everek, the deportation order was not published until early August. Twenty Protestant families were authorized to remain behind; the rest of the population was put on the road on 18 August. According to the survivors, the convoy reached Tarsus in 16 days. In several places, the local authorities had the deportees sign obviously ‘fictitious’ documents attesting that they had received aid, when in fact some of them died of disease or malnutrition and most of the others had been massacred in Der Zor. Of the 13,000 people deported from the kaza, approximately 600 seem to have survived in Aleppo and another 400 in Damascus.”[3]

In Tomarza and its environs, 200 of the city’s notables were arrested, tortured and threatened with death. “Twenty were then set free after paying bribes, and the rest were sent to the kaymakam of Everek. (…) In the course of (a) second operation, 196 men were arrested and deported to Hacın [Hajn] by night. Only after liquidating nearly 400 men was the deportation order for the rest of the population issued. On 27 August 1915, the inhabitants of Tomarza were put on the road to Aleppo by way of Hacın, after being divested of their possessions in Çibaraz, not far from the city (…). Those in villages in the vicinity of Tashkhan apparently met a similar fate. By the time the convoy arrived in Aleppo, only 300 of the deportees were still alive. They were sent to Der Zor, Raffa, or Meskene, where most of them died.

According to a number of survivors, the worker-soldiers who were employed in an amele taburu, charged with putting up telephone lines in the region were put to death near Tomarza.”[4]