Dörtyol – Դորթյոլ / Չորք-Մարզպան(ք) – Chorkk’ Marzpan(k’) / Չորք-Մարզվան(ք) – Chork’-Marsvan(k’)

Located at the foot of the Amanos Mountains, the small town of Dörtyol is at the edge of the Cilician (Çukurova) Plain. Being near the coast, the climate is humid, and the countryside is fairly green and fertile. Therefore, alongside oil handling, the economic activities of the area include forestry, cotton, and the cultivation of citrus fruits, especially a local variety of tangerines. Until 1915, it was an Armenian town surrounded by Turkish villages.

Toponym

The Turkish placename Dörtyol means literally ‘four roads’, i. e. ‘crossroads’. Its Armenian name was Chork’ Marzban (Western Armenian: Marzpan) or Chork’ Marzvan.

Population

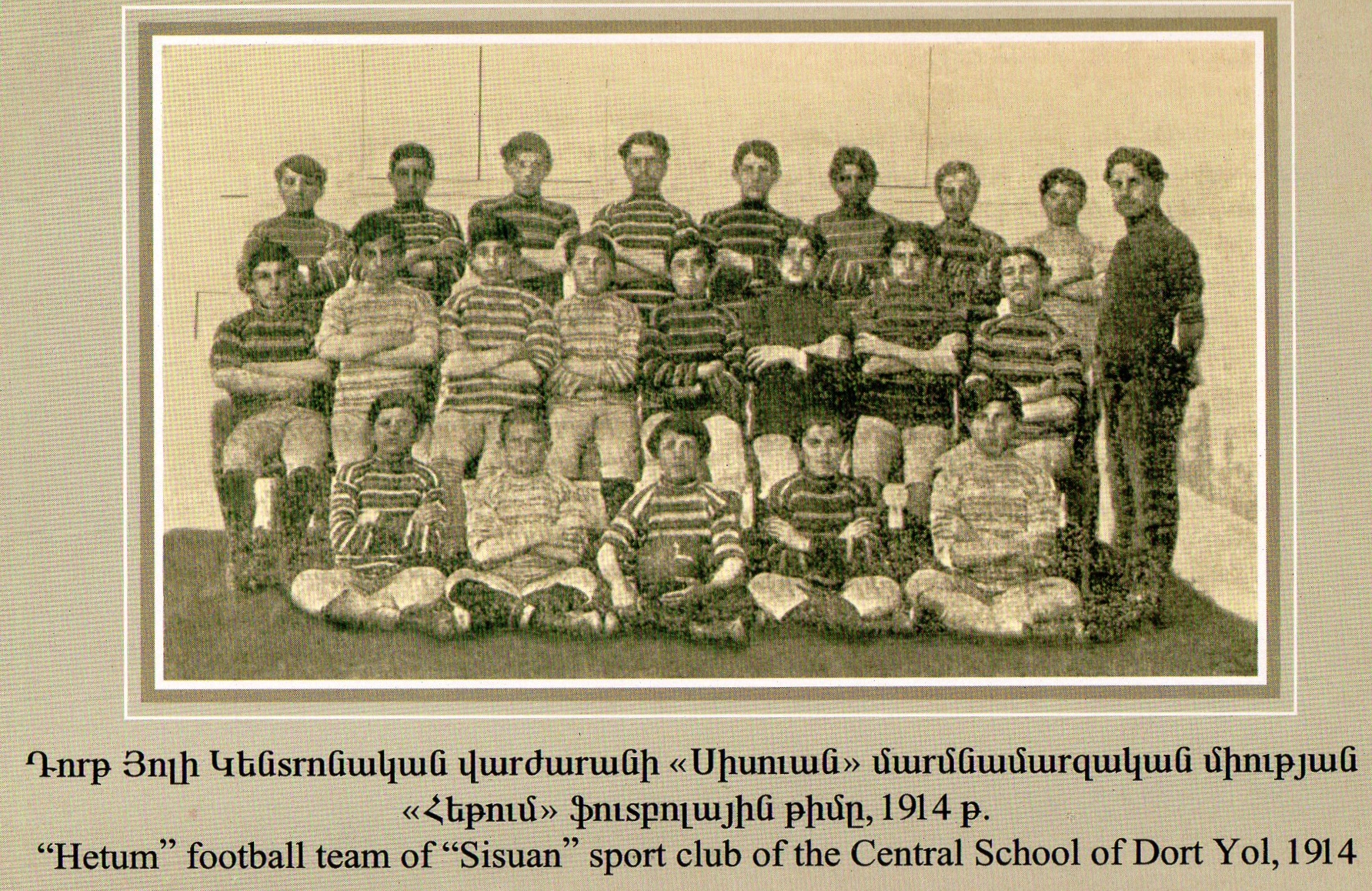

In 1908 Dörtyol had 8,000, and on the eve of the First World War 12,300 Armenian inhabitants. The main occupation of the population was handicrafts, trade, cultivation of subtropical cultures. There was an Armenian church and an Armenian college in Dörtyol.[2]

History

This crossroads has seen the passage of numerous armies and some of the biggest military campaigns in history, including the Battle of Issos between Alexander the Great and Darius in 333 B.C.

The town of Payas, which was in the hands of the Ulaşlı tribe and especially the Küçükalioğulları belonging to this tribe, was situated in a highly important location where the pilgrimage route to Mekka passed.

Administration

As of 1568, Payas was the seat of the Üzeyir sancak of the province of Aleppo.

History

Discoveries from the time of the Hittites prove a settlement of the area at least since the 2nd millennium before Christ. Numerous Hittite graves, especially in the eastern part of the city around Karabeyaz, testify to an important settlement that was located on the important road from Anatolia to Syria. From about 540 BC Payas belonged to the province of Syria in the Persian Empire. The first significant appearance of the town in history was in the Battle of Issos, 333 B.C. Alexander the Great passed through the town and followed the royal road to Persia in search of the army of the Persian king Darius III. When he learned that Darius was advancing on Issos behind his back, he turned back and camped in Payas in November. After this battle, Payas belonged to the empire of Alexander the Great. After Alexander’s death, Baias was part of the Seleucid Empire. In 63 BC, the Roman commander Pompey put an end to the Seleucids and Payas became part of the Roman province of Syria.

During the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, Payas was one of the theaters of war between emperor Heraclios and Khosrow II. In the second half of the 7th century, Payas became a part of the rising Arabic Empire. Seljuk Turks annexed Payas towards the end of the 11th century. The town was contested between the Turks and the Byzantines, but was captured by the armies of the First Crusade in 1097. It became part of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia soon thereafter. From 1137 to 1138 Emperor John II succeeded in reconquering Cilicia for Byzantium, but under Prince Toros II Payas again belonged to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia from the second half of the 12th century.

In 1266 or 1268, the region was captured by the Mameluk Sultanate. Later, the town became a part of the Beylik of Dulkadir. With the connivance of the Mamelukes, Turkish pirates under Oruç Reis used Payas as a base to disrupt Venetian trade with Cyprus. At the beginning of the 16th century, a naval battle took place off Payas between Venice and the Turkish pirates, during which the pirate ships were sunk. In 1516, the Ottoman Sultan Selim I passed through Payas on his way to Egypt and conquered the Beylik (principality) of the Ramazanoğulları for the Ottomans. In 1567 to 1568, a shipyard was built in Payas under Sultan Selim II, where ships were built for a planned invasion of Cyprus. Since Payas was on the way to Mecca and on the strategically important road to Syria, the old Genoese castle was razed in 1567. A new building was erected until 1571, which can still be seen today. In gratitude for the successful conquest of Cyprus, the Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha had a caravanserai with a mosque, bathhouse, bazaar and Koran school built between 1571 and 1574.

From the 18th century Payas’ importance decreased more and more, the number of inhabitants decreased and Payas became an insignificant provincial town.

Population

Payas, the old center of the sancak Cebel-ı Bereket, had a township called Yumurtalık, and there were 13,207 Muslims and 3623 Christians in the district.[1] However, this figure, given by Yusuf Halacoğlu in the DITIB Encyclopedia of Islam, is certainly too low.

April 1909: Self-Defence in Dörtyol

“When the news of the Adana massacre reached Dörtyol on April 15, around 3,500 Armenians from surrounding villages such as Ocaklı and Özerli poured into the town. The Armenians acted preemptively and took over the town’s military barracks. This was interpreted by the Muslim population as a clear act of uprising. A telegram sent on April 20, 1909, by the mutasarrıf of Cebel-i Bereket, Asaf Bey, to the president of the Chambers of Deputies stated that the Muslims surrounding Dörtyol were on the defensive and not the offensive, while Armenians were attacking the villages. He asked for immediate dispatching of soldiers.

The mob that soon surrounded Dörtyol was armed with Mausers and Martinis, which had been distributed by Asaf Bey. For more than twelve days, around ten thousand Armenians were besieged by a mob of seven thousand people composed of Kurdish and Circassian bands from the interior and Muslim inhabitants from the surrounding villages. More than four hundred of the besiegers were armed and received a steady supply of ammunition from the government. Led by Mihran Der Melkonian, the Armenians were able to resist, but on the second day, the mob grew, even bringing a canon. On the third day of the siege, Sunday, April 18, the besiegers cut offthe water supply to Dörtyol.

On April 21, the British ship Triumph, which had arrived at Iskenderun [Alexandrette] in the morning, carried fifty soldiers, local government officials, and Christian and Muslim notables to Dörtyol with the aim of calming down the situation. (…) Despite the fact that the besiegers ‘swore to observe a truce for two days and allow the water to be turned on again,’ they resumed their attack on Friday, April 23, ‘disregarding their oath completely.’ Further peace-keeping attempts did not yield any results. Belfante, the German vice-counsul in Iskenderun, attributed the deterioration of the situation ‘solely to the notorious incompetence of the Ottoman authorities to ensure the order and security of this unfortunate region.’

On Monday, April 26, after hours of negotations, the regular troops entered Dörtyol and took over the barracks, raising the siege and turning the water on. Aiding the refugees from the surrounding villages was a major problem: they had lost all their belongings, and their houses had been looted and burned down. In May, Dörtyol was put under martial law. The disarming of Armenians was problematic, as the Kurds, Circassians, and Turkmens who had been dispersed by the military troops and now surrounded the village [town of Dörtyol] were still armed.”

Excerpted from: Der Matossian, Bedros: The Horrors of Adana: Revolution and Violence in the Early Twentieth Century. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2022, pp. 123 f.

Destruction

During the massacres of 1895 and 1909 the Armenians of Dörtyol successfully defended themselves. These recent successes, as well as the presence of British warships in the Gulf of Alexandrette, made the situation of the Dörtyol Armenians particularly precarious during the Great War. They were accused of being agents for the Ottoman Empire’s wartime enemies.

A detailed contemporary report, written by the Armenian Simon Agabalian, who was an assistant official at the German consulate at Adana, was sent to the German Ambassador Wangenheim in Constantinople on 13 March 1915, indicating that behind the ‘Dörtyol unrest’ were just two or three local Armenian residents with links to the British fleet, which nevertheless served the Ottoman authorities as a pretext for mass arrests and forced labor among Dörtyol’s Armenian population.

“A few weeks ago, a former deserter by the name of Saldshian, who received his education from the local Jesuits and who later taught French at the Armenian school, went to Dört Yol. Two years ago he had gone to Cyprus and presently most likely has joined the English. He went together with an Armenian from Alexandrette to Dört Yol and stayed there for 6–7 days. You could almost say he tried to recruit the inhabitants for the foreign service. It is not known how far he succeeded and some merchants’ claim the trip involved Saldshian’s private business and had nothing to do with the general public. The notables of the village did not know about the visit and some of them were not even present at that time. Saldshian managed to obtain identity papers and introduced himself as a merchant. Even the police was informed of his presence. By sheer coincidence, after Saldshian returned to the English war-ship, the police became aware of the fake merchant, and could only arrest the man, who had accompanied him. A few days later another Armenian by the name of Köshkerian from the village of Ocaklı leaves the war-ship to come on land. After the murder of his wife during the massacre by the Turks he went abroad. This man is supposed to have carried money with him in the amount of 40 Ltq. From all these actions and occurrences one cannot deduct that the Armenians had any kind of organization for the purpose of a conspiracy or revolution. But one can surely say, that the arrival of the war-ships and their aggressive behaviour generated joy among the majority of the Christian populace and especially Armenians, and if it should ever be possible for the English or French to reach land, they would be extremely welcomed by the Christians. During one night all the male Armenians of the village were arrested and sent away from this area, due to the emphatic request from the Turkish population of the neighbouring residences to remove the Armenians from Dört Yol and because they wanted to arrest deserters and avoid any unforeseen actions. They were sent to Aleppo under strict supervision and are now doing roadwork. During the arrest the Armenians showed submission and did not resist the officials. Three people were shot while trying to flee. Even these did not use any weapons.“[3]

In his report to the German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, Ambassador Wangenheim summarized the information in the following way:

“At the beginning of March [1915], after Englishmen from the fleet had repeatedly landed and made some purchases undisturbed, there were two Armenians staying in the Armenian town of Dört Yol who originated from that area and who were acting on behalf of the English. One of these emissaries fell into the hands of the Turkish authorities and was executed in Adana. A further consequence was that the whole of the male population of Dört Yol was enlisted and led to the Vilayet Aleppo where they were set to building roads; three individuals, because they tried to flee, were shot down. Another fact was that at the time of these occurrences numerous deserters were in hiding in Dört Yol; also, it had not been forgotten that the townspeople had defended themselves against the Turks with their weapons in their hands during the massacre of 1909.”[4]