Population

Ayntab and its environs had a huge Armenian population since the tenth century. In the 14th century massive immigration started from different regions of Armenia, in particular from Mush, Malatya, Maraş, Birecik, Urfa, Adıyaman, and Besni (Armenian: Բեհեսնի – Behesni).

According to the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople, in 1914 there lived 36,448 Armenians in three localities of the Ottoman kaza of Antep, maintaining eight churches and 25 schools with an enrolment of 5,000 pupils.[1]

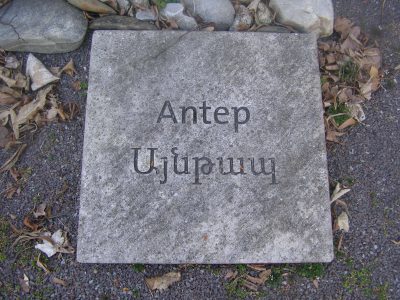

City of Antep / عينتاب – ʿAyintāb / Aintab / عنتاب – ʿAntāb / Այնթապ – Ayntap

Situated in southeastern Cilicia, on the Marash–Aleppo road, on the banks of the Sachuri (Սաջուրի ափին), which is a tributary of the Euphrates, the city spreads out in a highland valley, which is surrounded on the north, west and south by hills containing limestone, and marble. There are lush vineyards and orchards, quarries nearby. It is famous for its grapes, apricots, apples, walnuts and other fruits. Grain and cotton are also cultivated. Ayntab was famous as a trade and craft center.

Population

“Thirty-six thousand of Ayntab’s 80,000 inhabitants [around 1914] were Armenians from diverse religious backgrounds of whom 4,000 were Protestants. The community maintained several churches and 25 schools with a total enrolment of 5,000. Another several hundred young men and women attended Central Turkey College, which had been founded in 1876 by American missionaries and included a medical school as well as a hospital. The Armenian population of Ayntab, which had been Turkish-speaking since the mid-eighteenth century, had partially recovered its mother tongue thanks to the intense development of education, encouraged by the Constantinople Patriarchate down to 1915; this held for the youngest in particular. The Armenians of Ayntab, an especially active population, were employed above all in trade and the crafts a d held a key position in the economic life of the city.”[2]

“At the end of the 19th century, Aintab had 43,000 residents, of whom 16,900 were Armenian. In the early 20th century the number of Armenians was approximately 36,000. (…) Armenians were the majority of the jewelers, locksmiths, painter/dyers, curriers, and carpet-makers. The embroidery production of Aintab’s women was delicate and tasteful, and had a good reputation especially in Europe and the United States, and commanded high prices. Until 1915 Aintab had 6 Armenian churches including S[urb] Asdvadzadzin (ս Աստվածածին), S. Yeghia (ս Եղիա) and others, 17 places of education, schools and colleges (Vardanyan, Mesropyan Sanutz School, founded in 1874, Adenakan Orbachnam School, founded in the same year, Haykanush College, founded in 1877, Vardanants Preschool, opened in 1882. The first Sunday school was opened in Ayntab in 1896; the Aydinyan and Hokhisimyan Colleges and the ‘Central Turkish Colleg’; in 1912 the Cilicia Seminary was founded with day and night sections). Armenian Turkish newspapers Yeni Yomur” and Hagigat were also published in Ayntab.”[3]

Prominent Armenians from Ayntab

- Bedros A. Sevadjian (1918-1977): “Jeweler to an Emperor”

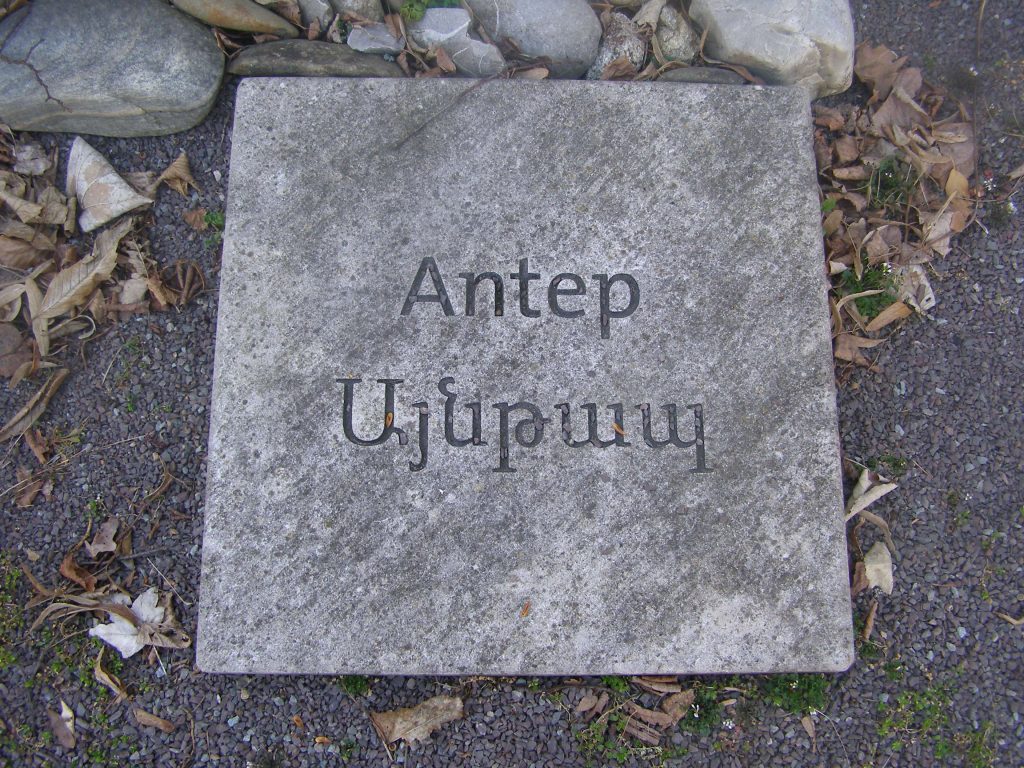

- Luther George Simjian (Armenian:Լյութեր Ջորջ Սիմջյան)(28 January 1905- 23 October 1997): Armenian-American inventor of numerous devices and owner of over 200 patents. Inventions include Medical photography systems, Autofocus camera, Automatic Developing machine, Automatic Teller Machine (ATM), Military flight simulator, Postage Meter and many other things.

History

In ancient times, the territory of today’s city was disputed between the Hittites and the Assyrians for a long time and came to the Assyrians through King Sargon II (721-705 B.C.). After their invasion of Eastern Anatolia, the Turkish Seljuks, who had defeated the army of Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes (1068-1071) in the Battle of Manzikert on 26 August 1071, took possession of this area.

Although Ayntab is an old settlement, the first official information about it was reported by the crusaders (11-12th centuries), who built a strong fortress here and made it their military base. In the Middle Ages, Ayntab was part of the county of Edessa, then for a short time it passed into the hands of the Armenian prince of Cilicia, Vasil the Thief.

In 1183, Sultan Saladin conquered the city. After his death in early March 1193, the rule in this area was disputed, among others between Mamluks and Mongols. In 1266, Cilicia’s King Hetum I made two unsuccessful attempts to incorporate Ayntab into his kingdom. In 1404 Ayntab was destroyed by Timur Lenk. In 1516 the Turks captured Aintab.

At times Antep belonged to the Beylik of the Dulkadir. In 1514, the Ottoman Sultan Selim I (1512-1520) conquered southeastern Anatolia, and with it Antep. Since then, the city belonged to the Ottoman Empire; between 1832 and 1840 it was occupied by the troops of the Egyptian governor Muhammad Ali Pasha. At the end of the First World War, British units occupied the region in 1918; they were followed by the French until their expulsion by Sahin Bey in 1921. The Kemalist Turks took over the administration of Antep on 4 December 1921, and the French evacuated on 25 December. “Many Armenians left with the French, though about 3,000 remained. (…) during the following months they were subjected to a quiet, and then very public, boycott, and a few were charged with pillaging or other offenses. In June 1922 Turkish ruffians raided the ‘shops of packsaddlers, farriers, and Koshker [slipper makers] in the Odoun Bazaar’ and threatened customers. The French military cemetery was desecrated.”[4]

With the Treaty of Lausanne on 24 July 1923, the now Gaziantep became part of the Republic of Turkey.

Destruction

October 1895

“Fear gripped local Christians, who worried that the fate of Trabzon and Sason would soon befall them. They shut themselves in their homes. Unable to work out of doors and shop in town, ‘thousands are without food,’ a missionary reported. ‘Over 1,000 men’ had fled to ‘mosques and khans and houses of powerful Moslems’ where they obtained shelter but lived as virtual prisoners.

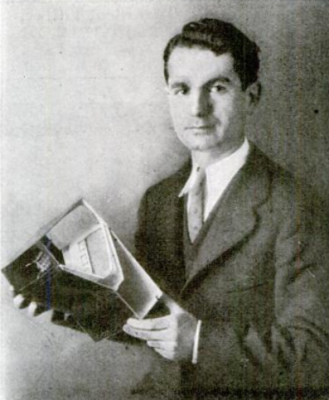

Americus Fuller, a missionary and president of the town’s Central Turkey College, believed—or hoped—that Antep would escape the suffering that befell Armenians elsewhere. Circumstances in the town were different: the Christians were ‘exceptionally intelligent and influential’ and ‘the leading Moslems . . . able men’ who ‘have shown themselves to a degree tolerant of and even friendly to Christians.’ Furthermore, ‘the Governor has seemed disposed beyond most Turkish officials to respect the rights of Christians,’ the town had a relatively large contingent of foreigners ‘sure to be witnesses of any violence done to Christians,’ and the missionary hospital and college had generated ‘good will’ among ‘all classes.’ Moreover, the town’s Christians had ‘given very little countenance to the ultra-revolutionists.’ Still, there was no mistaking the repeated threats of anti-Christian violence, and the local government largely disarmed Christians while arming Muslims, allegedly to put down a possible Armenian uprising.

The violence caught up with Antep on November 16, when the missionaries, at breakfast, heard ‘a great noise of shouting and firing of guns . . . telling us that the work of blood and plunder had begun. Crowds ran to and fro, and the roofs were covered with excited men, women and children.’ Missionary physician Fred Douglas Shepard rode his horse through the town and heard, ‘most terrible of all, the shrill, exultant lu-lu-lu of Kurdish and Turkish women cheering on their men to the attack.’ Fuller too remarked on the ‘loud shrill Zullghat . . . raised by Turkish women crowded on their roofs and cheering on their men to attack.’ (…) Shepard and Fuller saw Armenians assaulted and their homes looted. Armenians, ‘women . . . often foremost,’ defended their homes from the rooftops with ‘stones and firearms.’

Some mobs were beaten back, but where Armenian houses were isolated, the rioters broke through, plundering and torching. In certain areas, the ‘uproar went on till near midnight.’ Hamidiyes took part in the massacre, while other troops protected the missionary schools and hospital from the mob but made no attempt to stop the violence. Indeed, they took part in the looting. Missionaries watched villagers leave the city loaded down with stolen goods. Weeks later army deserters were seen in the streets of Aleppo selling their loot. A Franciscan priest who witnessed the massacre later told (…) that ‘butchers and tanners . . . armed with clubs and cleavers’ were prominent among the killers. They screamed ‘Allahu Akbar’ as they broke down doors ‘with pickaxes and levers or scaled the walls with ladders’ and then cut down the Armenians they encountered. ‘When mid-day came they knelt down and said their prayers, and then jumped up and resumed the dreadful work. . . . Whenever they were unable to break down the doors they fired the houses with petroleum.’

The plunder and massacre continued the next day, after Turkish villagers entered the town, brushing past a cordon of soldiers. Kurds, ‘waving a green flag and beating tomtoms,’ tried to join the villagers but were blocked by the mufti and soldiers ‘because it was feared that they would plunder Moslems as well as Christians.’ This time the Christians were prepared and repulsed their assailants. ‘At one point on the line of defense were a few Muslim houses and we were delighted to learn that the men heartily and bravely joined in the defense with their neighbors,’ Fuller recorded. But ‘the gallantry of this act was somewhat marred . . . by the demand which they made the next day for a large sum of money for this service.’ The men received ‘about five dollars apiece for this neighborly help.’ Some Muslims ‘behaved with great humanity’ and protected Armenians. Even so, ‘not less than 400’ Armenians were killed, according to Shepard. Fuller reported that Muslim casualties amounted to no more than twenty-five killed or seriously wounded.

Following the massacre, Antep’s prisons were crammed with Armenians. In January 1896 some 750 were still ‘shut up in the Armenian church,’ and all Armenian shops remained closed. Four thousand people depended on charity ‘for daily bread.’ Barnham suggested that the continuing, wholesale arrest of wealthy Armenians was in large measure designed to enable expropriation. The arrests may also have been used to press for conversion. As Antep’s leading Muslim notables, including the new kaymakam, told the Armenians after the massacres, there was now ‘no hope of their living in security unless they will become Mohammedans.’ By March, it was reported that at nearby Cibin all but one of the 500 or so Christians were forced to profess Islam. The exception was a ‘lady over 110 years of age’ who told her tormentors, ‘I am too old to change my faith. I know no one but Christ.’ Many converts were robbed. Christian graveyards were desecrated, the bones carried off and scattered, and Christian- owned trees were destroyed.

No Antep Muslims were punished, and the authorities systematically portrayed the Christians ‘as the aggressors.’ In June 1896 Lufti Pasha, the newly appointed commander of the reserve troops at Aleppo, tried to restore Christian property and bring the plunderers to justice. But his efforts came to naught after arrests of robbers led to a mass demonstration of Muslims in Antep. The detainees were soon released. Some threw stolen property into the street or burned it to protest Lutfi Pasha’s offenses against impunity.”

Excerpted from: Morris, Benny; Ze’evi, Dror: The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities 1894-1924. Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press, 2019, pp. 93-95

1915

The Armenian-French historian Raymond Kévorkian points out that initially there were no plans to deport the Armenian population in Aleppo province.[5] In the sancak Antep, however, those in the C.U.P. circles who demanded deportation also in their sphere of power and office prevailed.

Johannes Lepsius summarized the events in 1916 as follows: “In Aintab at the end of May [1915] thirty houses were searched without success, 28 notables arrested and released again except for one member Dashnaktsakan. This, however, was only the prelude.” [6]

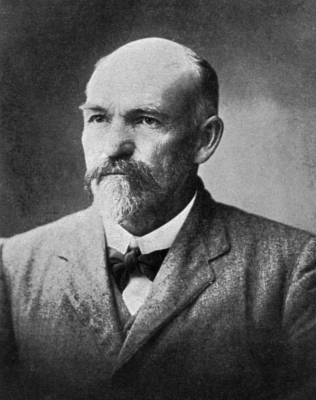

Lepsius quotes U.S. physician and contemporary witness Dr. Fred Douglas Shepard (11 September 1855 – 18 December 1915), who died in Ayntab after contracting typhus from Armenian deportees:

“In Aintab, on July 21, the deportation order was given for 60 families. A few days later, a second order came for another 70 families. Subsequently, another 1,500 and then 1,000 were sent, so that the Armenian population of Aintab was completely cleared out. All efforts to exempt the American institutes (their Armenian teachers’ families and employees, students) from this measure were unsuccessful. The deportees were forbidden to take with them even the most necessary belongings, except for a beast of burden.”

According to R. Kévorkian, a “meeting called on 29 July by the local Young Turks confirmed the reception of a deportation order emanating from Istanbul. At the meeting a list of the first Armenians to be sent off was drawn up. The German consul in Aleppo confirmed this information, informing his superiors the next day that the order to deport the Armenians from the coastal zones of the vilayet of Aleppo, Ayntab, and Kilis ‘had just been issued’. The American representative passed this news along to his ambassador a few days later, adding that the order also applied to Antakya, Alexandrette, and Kesab.

(…) The first convoy, made up primarily of notables and the members of the deportee relief committee, left the same day by the city’s western exit. A member of the city council, Nazaret Manushagian [Manushakian], was attacked and murdered there by the men of the Special Organization. The second convoy was methodically pillaged by çetes less than a day’s march from Ayntab. Every day, from 100 to 300 families were put on the road; at the same time the city’s Armenian neighborhoods were transformed into huge bazaars. (…) The authorities requisitioned all non-Turkish schools and all churches; they confiscated the stocks of the stores; they rented the most beautiful houses ‘at extremely low prices’ and attributed the others to Turkish families. The Armenian cathedral was transformed into a warehouse for ‘abandoned’ property and then converted into a stable after all the objects deposed there had been sold off. To facilitate certain transactions, the main beneficiaries of these acts of despoliation saw to it that the director of the Ayntab branch of the Deutsche Bank, Levon Sahagian, was rapidly deported. Sahagian would later be killed at Der Zor.

Apart from the first two groups, which were sent toward Damascus, all the Armenians deported from Ayntab were sent toward the Akçakoyun railroad station, where they were put in a transit camp surrounded by barbed wire while waiting to be loaded into stockcars and transported to Aleppo, and then sent on foot to the region of Zor. The American consul, Jackson (…) observes that, unlike the other convoys, those that came from Ayntab included men, women, and children over ten. (…)

Only after the Apostolic Armenians had been expelled did the authorities issue the order, on Sunday, 19 September, to deport the few hundred Catholics of Ayntab who had initially been spared. By late September, three quarters of the Armenian population had already been deported. (…) The Protestants were ultimately deported via the Akçakoyun railroad station, in falling snow, beginning on 19 December 1915, the day after Dr. Shepard was buried. (…)

Thus, the members of the Ittihad club and the local notables took a direct hand in the liquidation of around 15,000 Armenians from Ayntab who were deported to Der Zor. They organized, for that purpose, an executive committee made up off Dabbağ Kimzade, Nuribeyoğlu Kadir, and Hacihalizade Zeki, who went to Zor to make certain that the Armenians had indeed been put to death, so that they would not have to worry about returning their property to them. (…)

(…) a total of around 2,000 people were allowed to remain in Ayntab either throughout the war or for a few months, depending on circumstances. From January to July 1916, the mutesarif continued to deport small groups of Armenians to the south on various pretexts (…).

In the end, according to Armenian sources, around 12,000 Armenians from Ayntab survived the war and the deportations. Survivors were especially numerous among those deported by the Homs-Hama-Damascus route.”[7]

The Protestant Armenian community of Ayntab had raised all the means at their disposal in order to be deported by way of this route instead of the Aleppo-Zor route.[8]