The historical region of Ispir/Speri, also known as Sper (Georgian: სპერი Speri), was centered in the upper reaches of the valley of the Çoruh River. Its probable capital was the town of İspir, or Syspiritus. The region originally extended as far west as the town of Bayburt and the Bayburt plains. There are rich gold and other metal mines in the region, which were exploited in ancient times. Speri is mentioned in Greco-Roman, Armenian, Byzantine, Assyrian, Armenian, Georgian and Turkish sources.

Toponym

Ancient authors referred to Sper(i) as Cispiritis, Syspirites, Hesperitis and other names, deriving from the ethnonym Saspeires. According to the most widespread theory, they are a Kartvelian tribe. However, their origins have also been attributed to Scythian people.

Administration

Sper came under Ottoman rule by the Ottoman-Iranian treaties of 1555 and 1639. The Ottomans divided Sper into two parts: Baberd (Bayburt) with the center of the same name, and the town of Sper and its surroundings, which first joined the Erzurum province as sancaks (livans).

Population

In the 17th century, Sper was purely Armenian. Hakob Karnetsi (Jacob of Karin/Erzurum) mentioned that the inhabitants of Sper were completely Armenians. The raids and repeated wars of the various conquerors of the 16th-17th centuries destroyed Sper. The deportation organized by Shah Abbas I at the beginning of the 17th century caused great damage to Sper as well. At the end of the 17th century, thousands of Sper Armenians fled the Ottoman persecution, and many of the rest were forcibly converted to Islam at the beginning of the 18th century. The population of Armenians decreased further during the emigration of 1829-1830, when more than 1,000 families moved from Bayburt and Speri to Akhalkalaki and Akhaltsikhe.

In 1909 Sper had 134 settlements, 18 of which were purely Armenian. In addition to Armenians, Turks, Greeks and Laz lived in the kaza.[1]

According to the statistics of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 2,602 Armenians in 17 localities of the kaza of Ispir on the eve of the First World War. They maintained 17 churches, one monastery, and 13 schools with an enrolment of 459 pupils.[2]

The inhabitants of the kaza of Speri engaged in gardening, animal husbandry, cultivation of grain and oil crops, fruit growing, beekeeping, mining (Vank-Maden silver mines were famous), handicrafts. Armenians and Greeks were engaged in handicrafts and trade. Significant amounts of honey and beeswax were exported to neighboring provinces.

Settlements with Armenian population

Sper (administrative center), Akntos, Aghbnots, Aghburik, Ankejik, Avtdzor, Bakhchavank, Bakis, Gandz, Geghnadzor, Gogh (Kogh), Goghonts (Koghonts), Goshmshat, Darbni, Drakht, Zagos, Egedzor, Eshkents, T’ap‘dzor, Khachaghbyur, Khart’ik, Khzht’ar, Khozaghbyur, Tsaghkots, Kay, Karagyavur, Karakhach, Karmrik‘, Koshmashat, Hizpa, Hishents, Hngamak, Hoghek, Hunut, Dzknajur, Ghazents, Tsipot, Tsitkuns, Mants (Matsutsants), Mets Agrak (Mezgrik, Mezegrek), Moghoshen, ‘Nakhntsir, Nshenut, Shahristants, Tsikunts, Chap‘ants, Jerais, Jurakents, Salachor, Semekrik, Sitahank‘, Vagshen, Vahnas, Vargur, Vardenik, Varizonts, Tankes, Tandzut, Tghants, Tshadzor, Tup‘, K’alkunts, K‘aghonos, K’arap‘, K’ardzor, K’reoz, Odzut, Orsor.

Սպեր (վարչական կենտրոն), Ակնտոս, Աղբնոց, Աղբուրիկ, Անկեճիկ, Ավտձոր, Բախչավանք, Բակիս, Գանձ, Գեղնաձոր, Գող (Կող), Գողոնց (Կողոնց), Գոշմշատ, Դարբնի, Դրախտ, Զագոս, Էգեձոր, Էշկենց, Թափձոր, Խաչաղբյուր, Խարթիկ, Խժթար, Խոզաղբյուր, Ծաղկոց, Կայ, Կարագյավուր, Կարախաչ, Կարմրիք, Կոշմաշատ, Հիզպա, Հիշենց, Հնգամակ, Հողեկ, Հունուտ, Ձկնաջուր, Ղազենց, Ճիպոտ, Ճիտկունս, Մանց (Մացուցանց), Մեծ Ագրակ (Մեզգրիկ, Մեզեգրեկ), Մողոշեն, Նախնծիր, Նշենուտ, Շահրիստանց, Ծիկունց, Չափանց, Ջերաիս, Ջուրակենց, Սալաչոր, Սեմեկրիկ, Սիթահանք, Վագշեն, Վահնաս, Վարգուռ, Վարդենիկ, Վարիզոնց, Տանկես, Տանձուտ, Տղանց, Տշաձոր, Տուփ, Քալկունց, Քաղոնոս, Քարափ, Քարձոր, Քրեոզ, Օձուտ, Օրսոր։[3]

History

In the 2nd millennium B.C. on lands of Sper was an ancient confederation Hayasa-Azzi who were the proto-Armenians.

Late antique Sper was part of Armenia and is probably the Syspiritis of classical authors. Syspiritis is mentioned in Strabo‘s Geographica: one of two areas (the other being Acilisene) settled by followers of “Armenus of Armenium“, the eponymous founder of the Armenian ethnos. Strabo also mentions “mines of gold in the Hyspiratis”.

During the Artaxiad period (190 B.C. – 1 A.D.), Sper was an integral part of Greater Armenia (Armenia Maior). After the partition of Greater Armenia (387), Sper was one of nine districts forming the territory of the Armenian kingdom of Arshak III. It was the hereditary domain of the Bagratuni. Their princely center was the fortress town of Sper. In the northern part of the principality was a territory lived in by non-Armenian people called Chalybes, whose name was preserved in the alternative Armenian name for the Sper valley: Khaghto Dzor (Chaldian Valley). After Arshak’s death, in 390 his kingdom was annexed by Rome and turned into a Roman province.

In the 7th century Geography of Anania Shirakatsi Sper is listed as being part of Bardzr Hayk (‘High’ or ‘Upper Armenia’). The border between Byzantine-ruled and Sasanid Persian-ruled Armenia crossed the Choroh valley somewhere between İspir and Yusufeli.

Sper was a Bagratid domain in the fourth to sixth centuries but at some point they lost direct control of Bayburt to the Byzantine empire, possibly soon after 387. Bayburt was refortified by the Byzantines in the period of Justinian I and was eventually incorporated into its theme of Chaldia.

From 885, Sper was again part of the Armenian Bagratuni kingdom. At the end of the 11th century, Speri was conquered by the Seljuk Turks. In 1203, Rukn ad-din Suleiman II of Rum decided to capture the southern shores of the Black Sea and rule over Asia Minor. He invaded the Kingdom of Georgia with 400000 Muslim warriors and took control over several southern Georgian provinces including Speri. In the same year, by winning in the Battle of Basiani, Georgia managed to banish the Turks and liberate the region of Speri again. In 1204, Sper was captured and annexed to the Byzantine Empire of Trebizond. In 1207, Armenian-Georgian troops, led by Zakare I and Ivane I Zakarian, liberated Sper for a brief period. In 1242 Sper was conquered by the Mongol hordes that invaded Upper Armenia.

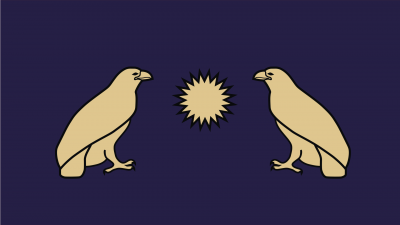

In the 15th century Sper was controlled by the Turkmen Ak Koyunlu confederation. In 1502, after the defeat and collapse of the confederation, its territory passed into the hands of Safavid Persia; however, Ak Koyunlu rule continued in Sper until, taking advantage of the dissolution of the Ak Koyunlu state following the death of Yakub, it was taken by Mzechabuk, the Atabeg of Samtskhe. Mzechabuk pursued a policy of appeasement with the Ottoman Empire and surrendered Ispir fortress to Sultan Selim I in October 1514. The Ottoman Empire had taken all of Sper from Mzechabuk probably by 1515.

In 1548, during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–55), the towns of Ispir and Bayburt were taken and destroyed by the Safavid Shah Tahmasp.

During World War I, in 1916 the region was taken by Russians forces and retaken by Ottoman forces in 1918.

Destruction

In 1895-1896, the Christian Armenians of Sper were subjected to the Hamidian massacres.

“We have only an indirect account about the kaza of Ispir, which comprised 17 small villages with a total Armenian population of 2,602. Thanks to this account, we know that these villagers were exterminated where they were found toward mid-June 1915 under the direct supervision of Bahaeddin Şakir and the çete leader Oturakci Şevket.”[4]