Administration

In the 16-18th centuries the sancak of Mush was a part of Van (Kurdistan) Province. In the 19th century it was integrated into the Bitlis vilayet. As of the early 20th century, the sancak was sub-divided into 5 the five kazas of Mush, Bulanık, Malazgirt (Manazkert), Vardo and Genç, which together comprised 567 settlements.

The southern part of the district consisted of the Armenian Taurus and the Sasun mountain ranges, and the eastern part of the Kopi mountain range. The highest peaks were Andok, Kepin, Kurtik, and Maratuk. In the west is the Mush plain. The main rivers of the district were the Eastern Euphrates (Grk.: Ἀρσανίας – Arsanias, Arm.: Aradzan; Trk.: Murat), Meghraget and its left tributary, the Khulp and Sasun rivers. Due to the rivers, the sancak was rich in drinking and irrigation water.

The climate of Mush is cool and healthy. In the kazas Bulanik and Manazkert the most fertile lands of the sancak is to be found, and in the sancak’s south shady forests and pastures. The district has a rich flora and fauna. The most common forest trees were oak and ash trees, furthermore fruit trees, such as apple, pear, and walnut. The owners of the forest trees produced a sweet honey-like juice from the pollen, which is called manna.

History

The Ottoman sancak (district) of Mush roughly corresponded to the Armenian county Taron of the Turuberan region of Greater Armenia.

Richard G. Hovannisian: Taron / Turuberan / Mush

“Taron, later incorporated into the larger medieval principality of Turuberan, was a wellspring of Armenian life since antiquity. The middle course of the Eastern Euphrates (Grk.: Ἀρσανίας – Arsanias, Arm.: Aradzan; Trk.: Murat) and other tributaries of the Euphrates flow through the fertile plain with the town of Mush at its center. (…) The rich dark soil made the plain a breadbasket, producing many kinds of grain, vegetables, and fruits. The surrounding mountains were rich in gold and iron ore, and their alpine pastures sustained countless flocks of sheep, goats, and other small-horned animals.

Taron was a core district of the ancient Araratian/Urartian kingdom. Here as Ashtishat, a major religious, political, and economic center intrinsic to the history of both pre-Christian and Christian Armenia. This was the site of the most important pagan temple complex of Armenia, and nearby was the birthplace of Mesrop Mashtots, creator of the Armenian alphabet and the sainted propagator of Christianity. This was (…) the focal point of the Armenian struggle against the powerful empires of the south and east – Achaemenid and Sasanian and then Arab and Turkic.

The heroic Mamikonian clan spearheaded that struggle for half a millenium before it was bled white and pressed out of the area late in the eight century. The momentary vacuum was quickly filled by the ascendant House of the Bagratuni, which gained possession of Turuberan as well as recognition and ultimately a royal crown from both Baghdad and Constantinople. But the tenth century brought an end to direct Armenian rule in Taron/Turuberan, as decades of Byzantine rule were followed by centuries of Turkic-Mongol-Ottoman domination.”

Excerpted from: Hovannisian, Richard G. (Ed.): Armenian Baghesh / Bitlis and Taron / Mush. Fresno, California: Mazda Publishers, 2001, p. 3f.

Population

Mush was one of the most densely populated areas in Western Armenia, with nearly 100 Armenian villages dotting the plain of Mush (Msho Dasht). In 1891, Mush had a population of 123,459, of which 55,365 were Armenians and the rest were Turks and Kurds. Before, Armenians made up the overwhelming majority of the province’s population.

Economy

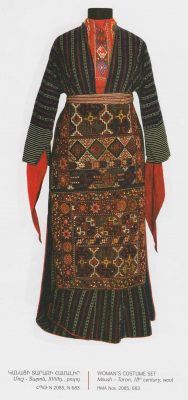

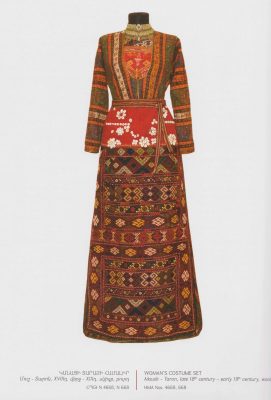

The main occupation of the population was cattle breeding and agriculture. In Meghraget, in the valleys of other rivers, in the kazas Bulanik and Manazkert, viticulture and fruit growing were widespread (grain, cotton, selected types of tobacco, rice, flax, hemp, sesame, lentil crops, and fodder). Mush was famous for its fine wines and its dried fruits. Among the crafts were weaving, painting, shoemaking, ironwork, and pottery.

Most of Mush’s products were sold in neighboring provinces.

Mush has the best types of iron, oil, sulfur, mill and earth.

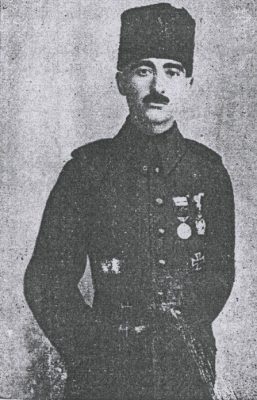

Destruction

“The eradication of the 141,489 Armenians of the sancak of Mush and the destruction of the 234 towns and villages in which they lived constituted an objective that was incomparably harder to attain for the Turkish authorities than cleansing Bitlis and Siirt of their Armenian populations. The two conscription campaigns of August 1914 and March 1914 had drained the area of its vital forces (…), and considerably diminished the Armenians’ ability to defend themselves. For the authorities, the priority was obviously to extirpate the population of Sasun and take control of its mountain fastnesses. In May (1915), they launched their first attack on the area with support from Kurdish tribes – the Beleks, Bekrans, Şegos, and so on – which they armed. This attack was repulsed. (…) The failure of the offensive against Sasun conducted by the Kurdish çetes probably convinced the young Turks to appeal exceptionally to ‘regular’ troops in order to get the better of this dense cluster of Armenians. (…) But the authorities also needed to mobilize local forces to maximize their chances of success. They were greatly aided in this by the June arrival in Mush of a key personage, Hoca Ilyas Sami, a Kurdish religious dignitary and a member of the Ottoman National Assembly. Sami, who galvanized the Muslim population of the region, does not appear to have returned from Constantinople by accident. (…)

The fact that he was a high religious dignitary endowed him with considerable prestige, which he used to preach the jihad in the city’s grand mosque. Yet, like the local notables, he was doubtless only executing orders received from Lieutenant-Colonel Halil (Kut), one of the leaders of the Teşkilat-i Mahsusa. The first measure to be taken after the 8 July arrival of Halil’s Expeditionary Corps at Mush was designed to bring all the access routes to the city under control and cut off communications between the localities of the plain, which were attacked the next day by squadrons of çetes under the command of Haci Musa Beg. In the days preceding the attacks, the same çetes confiscated arms in the villages after systematically torturing the villagers into revealing where they had hidden their rifles. (…) The çetes would encircle a village, round up the men, tie them together in groups of 10 to 15, lead them from the village, round up the men in a nearby orchard or field. Then they would shut the women and children up in one or more barns, picking out children and the ‘prettiest’ young women for themselves before dousing the building(s) with kerosene and burning those inside alive. Finally, they would plunder the village and then burn it to the grounds.

An eyewitness account given to a French press correspondent who was in Istanbul during the trial of the Young Turk leaders describes the case of 2,000 women who were surrounded by these Kurdish çetes and ‘sullied and looted.’ The women were suspected ‘of having swallowed their jewels to keep them out of the bandits’ hands.’ Disemboweling them proved to be too time-consuming a job. They were therefore doused with kerosene and burned alive. The next day, their ashes were run through a sieve.”

No fewer than six days, from 9 to 14 July, were required to extirpate the Armenians from the plain of Mush and the northwestern kaza of Varto (nine villages with a total Armenian population of 649). Roughly 20,000 people managed to flee to the Sasun highland, near Havadorig, where they crowded into an area with a circumference of three or three-and-a-half miles, a veritable trap in which they found themselves surrounded, along with the rest of the Sasun mountain district.”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, p. 345 f.