Administration

In the late 19th century, the sancak comprised the six kazas of Denizli, Tavas (also Davas; Grk: Davazon), Çal, Buldan, Sarayköy and Garbikaraağaç (also Kara-Ağaç; today: Acıpayam)

Toponym

In Greek, the ancient city was called Attouda (Αττούδα).

The earliest spelling of the town is Ṭoñuzlu. The proper word ṭoñuzlu refers to ṭoñuz (pig). Thus, it was initially a place full of pigs. In Ibn Battuta‘s Seyahatname (14th c.), the city is called Dūn Ġuzluh, which Ibn Battuta himself translates as ‘city of pigs’. This designation possibly goes back to the presence of Christian pig breeders in the city. Already with Timur a euphemistic transformation becomes visible. In his case, the name Tenguzluğ (from Old Turk. Tengiz for sea) occurs. Following this, the Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi in the 17th century traced the name of the city to the rivers and lakes of the surrounding area, because Tengiz or Deniz can also mean lake, river or simply water: “The city is called by Turks as (Denizli) (which means has abundant of water sources like sea in Turkish) as there are several rivers and lakes around it. In fact, it is a four-day trip from the sea.”[1]

Lâzıkıyye Denizli or Denizli Lâdik, as it was often called to distinguish it from ancient Lâdik (Laodikeia), can thus be translated as ‘water-rich Lâdik’. Several spellings corresponding to the meanings of Ṭoñuzlu and Denizli occurred in the course of the city’s history until the present name Denizli finally prevailed

Greek-Orthodox Population

Ecclesiastically, the sancak belonged to the Greek Orthodox Diocese of Philadelphia, which comprised twenty-nine communities with 21,138 Greek Orthodox inhabitants.

Town of Denizli

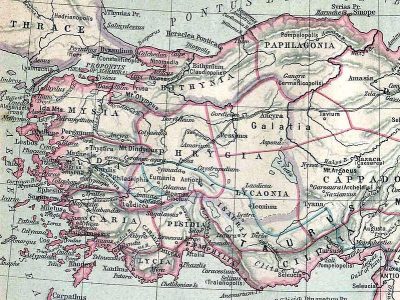

Denizli is situated in the eastern end of the alluvial valley formed by the river Büyük Menderes, where the plain reaches an elevation of about three hundred and fifty metres. Denizli is located in the country’s Aegean Region.

The ancient ruined city of Hierapolis, as well as ruins of the city of Laodicea on the Lycus, the ancient metropolis of Phrygia. Also in the depending of Honaz (also Khonaz, Cadmus, Colossae), about 16 km west of Denizli is, what was, in the 1st century A.D., the city of Colossae.

Population

In 1888, the town of Denizli had an overall population of 2,500.[2]

History

First settlements in the area of today’s Denizli are dated to about 4000 B.C. In antiquity, Denizli was an important Greek town, that existed through the ancient Greek and Roman eras; it was near the cities of Hierapolis and Laodicea on the Lycus and flourished through the Byzantine period.

The city was conquered by the Turks. The inhabitants of Laodicea were also resettled here in the Seljuk period.

Ibn Battuta visited the city, noting that “In it there are seven mosques for the observance of Friday prayers, and it has splendid gardens, perennial streams, and gushing springs. Most of the artisans there are Greek women, for in it are many Greeks who are subject to the Muslims and who pay dues to the sultan, including the jizyah, and other taxes.”

The city lived in peace for centuries without being involved in wars in a direct manner. Following World War I during the Kemalist Independence War, the Greek forces managed to come as close as Sarayköy, a small town 20 km northwest of Denizli, but did not venture into Denizli.

Destruction

Before and During the First World War

“The first serious manifestations of the hostile feelings of the Turks against the Christians of this Diocese [of Philadelphia] (twenty-nine Communities and 21,138 inhabitants) began by the commercial boycott, which the Government officials started suddenly, assisted by gendarmes, night- watchmen, and highway robbers whom they had expressly let out of prison, Rahmi Bey, Governor of Smyrna, personally inspected the application of this commercial boycott throughout the chief seats of the Diocese, and encouraged the fanaticism of the Moslems in their persecution of the Christians. (…)

One hundred and fifty-four persons were murdered: twenty-five at Philadelphia, thirty-two at Koula [Kula], twenty-eight at Salihli, and neighourhood, twelve at Ouchak [Uşak], twenty-two at Yordis and surrounding places; thirty-five at Denizli, Honnes and Diner. Among them was the director of the baths, Kodjamanides. One hundred and two fires broke out. The fanatical C.U.P.’s burnt the newly constructed Church and the school of Sardis [also Sardes].

Owing to these crimes the inhabitants of the less populated villages were obliged to resort to the more populated centres, while fearing a greater calamity, abandoned their country and business altogether, and went away to strange countries.

This partial expatriation took place particularly in the communities of Koula [Kula], Giolde, Demirdji [Demirci], Pitsirli, Giordes, Kayadjik [Kayacik], Borlou [Burlu], Mentochori, Outchak [Uşak], Otourak [Oturak], Sardis, Eniguiol, Denizli, Sara-keuy [Sarayköy], Elbanlar, Appa, Honne, Tsivril, Diner, Tatar, Guediz, Simar and Philadelphia.

When the Great War broke out, the sufferings of the Greek element of this Diocese reached their highest pitch. Requisitions, subscriptions by force, military exoneration taxes and general mobilization completely paralyzed all activity of this region. The Moslem landed proprietors took advantage of the mobilization of the Christians and took many of them into their service, but the treatment to which they subjected them was such as to cause the death of the majority.”[3]

Deportations 1916 until 1922

During and after the First World War, numerous deportations of the Greek Orthodox population took place from the town of Denizli, as well as to the sancak of the same name. Destinations for deportees from Denizli were Kayseri (c 1919), Germir (1919-20), Özlüce (Grk.: Silata; 1919-22), Eğirdir (1919-22), Özvatan (Grk: Tsouchour; 1920), Güzelyurt (1920) and Gesi (c1922).

Deportations to Denizli took place from Kayaköy (Grk.: Levisi, 1916, c1922) and Aydın (June 1919).[4] In the deportation from Aydın, the archdeacon of the Diocese of Ephesus, Ioachim Gounaris, was brutally murdered by Aegean irregulars (‘efes’, zeybeks) when he tried to save some girls deported from Aydın from being raped.

“After the destruction of Aidin 800 women and children were sent off to Nazli [Nazilli] and Denizli (on June 18 and 19, 1919) by railway. During the deportation a number of the people were killed, among them Archdeacon Joachim Gounaris (…). When the unfortunate people were installed in the place of exile, they were tortured in various ways. Some of them were compelled to work without pay, others had their clothing and covers taken away though they were the only objects they had brought there (…).“(5)

In her testimony Despina Papantoniou, a native of Fethiye, told: “Between 1916-1917 the Turks decided to remove the Greek population from the shoreline out of fear that Greece may land and would be helped by the local Christians. The deportation started in October 1916. I was the only woman who was deported with my husband, because I was a teacher. After a terrifying 15 day journey, we arrived at Denizli [approx. 170 km north]. Rain, cold, snow and typhoid were killing the people. We stayed at Denizli for two years – we worked and lived there – and when the Armistice arrived [October 1918], we were given permission to return to our homes. In September of 1922 an order was given to evacuate everyone from the shoreline. We were given 3 days to leave. We were only allowed to take a few things with us. We weren’t allowed to take gold and silver coins, in fact we weren’t allowed to have any jewelry on us at all. At our own expense we paid a fare to board a sailing ship which took us to Rhodes, and from there we were sent to Greece aboard Greek ships.”[6]