In ancient times, the Zimara-Malatya roads passed here, and in modern times, the Akn-Malatya roads.

Administration

In the Ottoman records of 1518, Arapgir was one of the twelve sancaks of the Diyarbekir province. At the time of Süleyman I, Arapgir became part of the Sivas province, and from 1834 it again belonged to Diyarbekir. From 1847 Arapgir became a part of the Vilâyet Mamuret ül-Aziz province (today Elazığ).

Toponym

The kaza’s administrative seat was also mentioned as Arabker. The name probably derives from the ancient city of Arabracnua, near which it was built. The city was ruled by the Arabs, some associate its name with the Turkish words ‘arab’ and ‘fat’ (‘gir’). According to Armenian folk etymology, Arabkir means by the river. The Byzantines knew the city under the name Arabraces.

Armenian Population

According to the 1914 census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 10,880 Armenians in five localities of the kaza Arapgir at the eve of the First World War, most of them in the administrative center Arapgir. They maintained nine churches, seven of them located in the city of Arapgir (among them two Protestant and one Armenian Catholic church) and 14 schools with 862 students (13 schools being located in Arapgir city).[1]

Five Armenian Settlements in the kaza Arapgir

Arabkir/Arapgir (administrative seat), Ambrka, Shepik, Ochakh, Ova.

City Arapgir / Արաբկիր – Arabkir

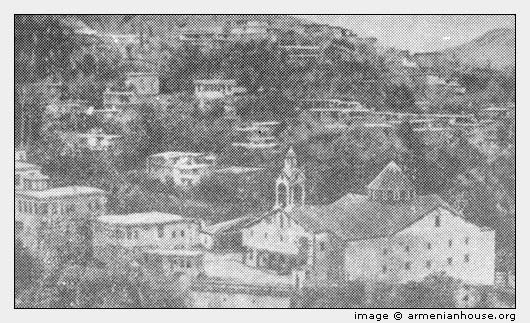

Situated on the banks of the Euphrates River and the Arapgir River the capital city of the kaza spread at the foot of the Antitauros mountain range. Arapgir stood out as a commercial city, surrounded by cultivated fertile fields. Most of the inhabitants were engaged in agriculture, cultivation of cotton, grain, orchards, and sericulture. Arapgir was known for its grapes and mulberries.

History

It is assumed that the place was settled since 1200 B.C. In 850 B.C. the Assyrians ruled here, in 612 B.C. the Medes and Persians. In ancient times, Arapgir was part of the Second Armenia of Armenia Minor, according to the administrative division of Justinian (6th century). The reconstruction of Arapgir is attributed to the last king of the royal dynasty of Artsruni of Vaspurakan, Senekerim-Hovhannes Artsruni, who in 1021 or 1022, in exchange for rendering his kingdom to Byzantium, received the region of Arapgir together with Sebastia (Trk.: Sivas).

Arapgir remained under Armenian rule until 1070. In 1178 the Seljuks of Rum ruled here. After they were defeated by the Mongols in the Battle of Köse Dağ, Arapgir became the property of the Mongols. After that, the Kara Koyunlu ruled. Arapgir came under Ottoman rule in the 15th century.

Arabkir was one of the literary Armenian centers. Several manuscripts were written here in the 15-17th centuries, of which we know from 1446.

Population

In 1800-1830, Arapgir had a population of about 15,000, of which 12,000 were Armenians. In 1830-1850, the number of Armenians dropped to 9,000. Before the genocide of 1915, the overall population of the city reached about 20,000, half of which were Armenians.

“(…) the Armenians were concentrated in the administrative seat, Arapkir, which had a population of 9,000 Armenians and 7,000 Turks. There were also four Armenian villages in the kaza: Ambrga [Ambrka] (pop. 250) near Arapkir, Shepig [Shepik] (pop. 468); Vank (pop. 129): and Antshnti (pop. 510). As everywhere else in these eastern provinces, trade and crafts, especially silk-weaving, were in Armenian hands, the countryside was populated mainly by sedentary Kurdish peasants, and the government and administration were a Turkish monopoly.”[2]

In the 19th-20th centuries, Arapgir first of all was famous for its canvas. In the middle of the 19th century, there were 15 weaving and 18 textile cloth production enterprises. Among the crafts were jewelry, metallurgy, copper, soap, and weapons. The trade was lively.

In the 20th centuries Arapgir had quite an intense cultural life. The Armenians had 13 schools here, among them Mother School, St. Translators, Zaruyan etc.

Before 1915, there were seven Armenian churches in Arapgir, of which only one remains in ruins today. The Cathedral of the Holy Mother of God (13th century) was one of the biggest churches in Western Armenia. It was able to house 3,000 people. The cathedral was attacked, looted and burnt in 1915 during the Ottoman Genocide. Later the cathedral was repaired and was used as a school. In 1950 the Municipality of Arapgir decided to demolish the cathedral. On 18 September 1957 the cathedral was blown up with dynamite. Later, the land where the cathedral stood was sold to a peasant named Hüseyin for 28,005 lira. Today, in place of the cathedral are ruins.

Nominable Armenians from Arapgir

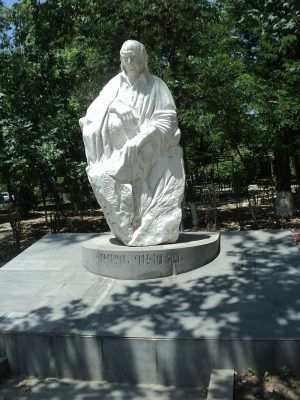

- Tadeos Astvatsatryan (1831-1906) – lexicographer

- David Bek (linguist) (Դավիթ Բեկ – Davit’ Bek, 1870-1938) – philologist, translator

- Vahagn Davtyan (1922-1996) – prominent Soviet-Armenian poet, translator, editor

Emigration and Remigration

Around 4,000 Armenians had emigrated to America and Egypt after the 1895 massacres, but maintained close ties to their homeland.[3] The surviving in Arabkir Armenians immigrated to Soviet Armenia in 1925.

On 29 November 1929, the 9th anniversary of the establishment of the Soviet regime in Armenia, the New Arabkir settlement was founded near Yerevan. The initial population of 1,000 inhabitants grew to 60,000 30 years later. New Arabkir merged with the capital Yerevan decades ago, forming one of the Armenian capital’s districts. However, after 1946, most of the Armenians who remained there migrated to Syria, Constantinople, and the city of Malatya (about 200 Armenians).

Destruction

The Armenians of Arabkir were twice, in 1895-1896 and in 1915 deported and exterminated.

Two Letters of Armenians from Arapgir, autumn 1895

“On 25 October 1915 (sic!; 1895), it was a Wednesday, the Metropolitan (Armenian spiritual leader) was summoned and ordered to give the Armenians the order to hand over all weapons. ‘But the Turks are all armed,’ the metropolitan replied, ‘it is up to them to start delivering the weapons’ … ‘That is none of your business,’ said the government men, ‘the Turks have the right to bear arms, and you have not; do as you are commanded, if not, you are doomed to die.’ These preparations were still in progress when, on Wednesday, at an hour in the afternoon, at the moment when the police were ordering the Armenians to surrender their arms, shots were suddenly heard and fires broke out in several places; the city was occupied. Two days earlier, criers had gone through the villages of Arabkir, proclaiming in the open street: ‘All those who are children of Muhammad shall now fulfill their duty, which is to kill the Armenians, loot and burn their houses; not a single Armenian shall be spared, this is the Sultan’s order. Those who will not obey shall be considered Armenians and killed like them.’ The people carried out the government’s order with uncanny precision. They began to murder and burn. The Armenians, frightened, left the houses, took refuge in the fields and on the mountains. Most of them were intercepted by the Turks on the way and met a horrible end. Some were thrown into the fire; others were hung upside down like sheep and strangled; some were cut to pieces with an axe or a sickle; others were doused with kerosene and burned; some were thrown on top of the unfortunates who had been set on fire with kerosene so that the smoke would suffocate them; several were buried alive; a large number were beheaded and their heads were hung on long poles. Often about fifty of them were tied together with rope, fired upon, and then cut to pieces with axes and sabers. Powder was sprinkled on the women’s hair, and then fires were lit (we will leave out the most hideous part). From every quarter the Armenians rushed to the Turkish notables to seek refuge and protection; only their doom they found, for with their own hands the notables killed even the Christians who humbly begged for help. They robbed our possessions, they strangled most of our people, they burned our houses, they violated our daughters and wives, they forced many of us to convert to Islam and killed those who refused.

… The dirtiest thing in this matter is that now, after all we have suffered, they want to force us to sign thank-you notes to the Sultan! They even want to make us say that it was us Armenians who did all this! Are they crazy, the Armenians, that they kill each other and one burns the other’s house? And Europe is so stupid that it is not ashamed of trying to deceive it by such absurd means? At least teach Europe anew about the events; would that it would come to save us! We are lost without its help. Our misery is too great. The women, old men and children who survived the massacre are coming back from the mountains where they fled, sick, half naked, hungry and thirsty, wandering from street to street, knocking on the doors of the houses that escaped the fire and begging. But no one has anything to give. People eat grass. Help us, my brother; help us soon. Appeal to the Europeans, appeal to the feelings of humanity! We are human beings and we are Christians. We have managed to preserve our nationality during the centuries of barbarism, and now that we have become a civilized people, you want to allow a barbarian government to destroy our race? What guilt have we committed? Why are we being made to suffer to such an extent?”

(From the letter of an educated Armenian woman:) “You shall have news of all this, but there is a great difference between hearing and seeing; what I am about to relate you will think is a dream. For eight days there was murder, looting and burning; there was an unspeakable tumult, infernal voices, wailing cries of little children, a horrible tumult such as has not been heard since the creation of the world. Children who cried out: O! God, Mama! … Others: who cried, Help! Help! Who will hear them? The bullets fell on us like hail. They come, saber in hand; never before have we seen people punished in such a barbaric way who are not guilty of any crime. We have nothing to put on our wounds, not even something to bandage them; we have no laundry to change with; the screams, the sighs do not let us fall asleep. If it really happens to us that we sleep for a moment, we are immediately awakened by the voices of children who, frightened by dreams, cry out: ‘They are coming, they are coming, Mama! They want to strangle us, throw us into the fire! Help!’

My aunt has already written to you and told you the number of our dead; they killed my father, they killed my grandfather, they killed my grandmother, they killed my mother’s uncle, but they didn’t kill my mother, which comforts us. They killed our friend B.C. and his wife. They left behind four little orphans who are crying and longing for their mother. A. and his wife were killed; they left behind five children, two of whom are still infants. They have no one to look after them; they are given boiled barley water. Oh God! God! God! You do not hear our voice, at least hear the voice of these little fatherless and motherless children! Since He did not hear our cries during the eight days of the bloodbath, when will He listen to our voice? We despair of Him; a hundred thousand times we have cried out to Him: ‘Lord, make the earth tear apart and devour us and free us from the hands of these executioners!’ He has not heard us, and now we say to ourselves: ‘Happy are those who died a natural death before this accursed time, without fire and sword’.”

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 2.: Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918, p. 606f.

Destruction in 1915

In the beginning of the First World War, 2,300 of the 3,000 men of draftable age in Arapgir left the kaza to serve in the Ottoman army. Over the winter 1914/5, gendarmes and policemen regularly searched Armenian homes for deserters, and “profited from the occasion by helping themselves to whatever they found.”[4] On 26 April 1915 Armenian businessmen who had avoided the draft by paying the bedel were arrested. But “it was not until 19 June that 30 of the men who had been detained were taken from the prison in chains and escorted beyond the city limits. (…) Only later did the inhabitants of Arapkir learn that this convoy was led to the bank of the Euphrates, piled onto a raft, and drowned in the middle of the river.

Two days later, on 21 June, a second group of 300 men, also in chains, was supposedly dispatched to Malatia, but in fact disappeared in the waters of the Euphrates. The last two convoys, each containing 250 men, set out on 23 and 24 June and met the same fate as the previous two. (…) The last men to be arrested, were the Catholic priest Reverend Krashian, the auxiliary primate Father Goriun, and the municipal physician Dr. Hagop Aprahamian, a native of Kütahya and the only civilian doctor in the city, were deported in the second convoy.(…)

On Sunday, 27 June, the town crier announced that the Armenian of Arapkir were to be transferred to Urfa, and that they had one week to sell their property and make preparations for the journey. (…)

The sole convoy from Arapkir, comprising more than 7,000 people, 250 of them adult males, set out on 5 July 1915 under the surveillance of approximately 150 çetes and gendarmes. (…)

On the twelfth day, 16 July, the authorities ordered the families to turn their daughters under 15 and boys under 10 over to them. The children were to be admitted to an orphanage in Malatia created especially for them. Between 3,000 and 5,000 children were loaded onto carts and taken away.

(…)

According to (an) (…) undated fall 1915 report to the minister of the interior, 8,545 Armenians were deported from Arapkir.”[5]