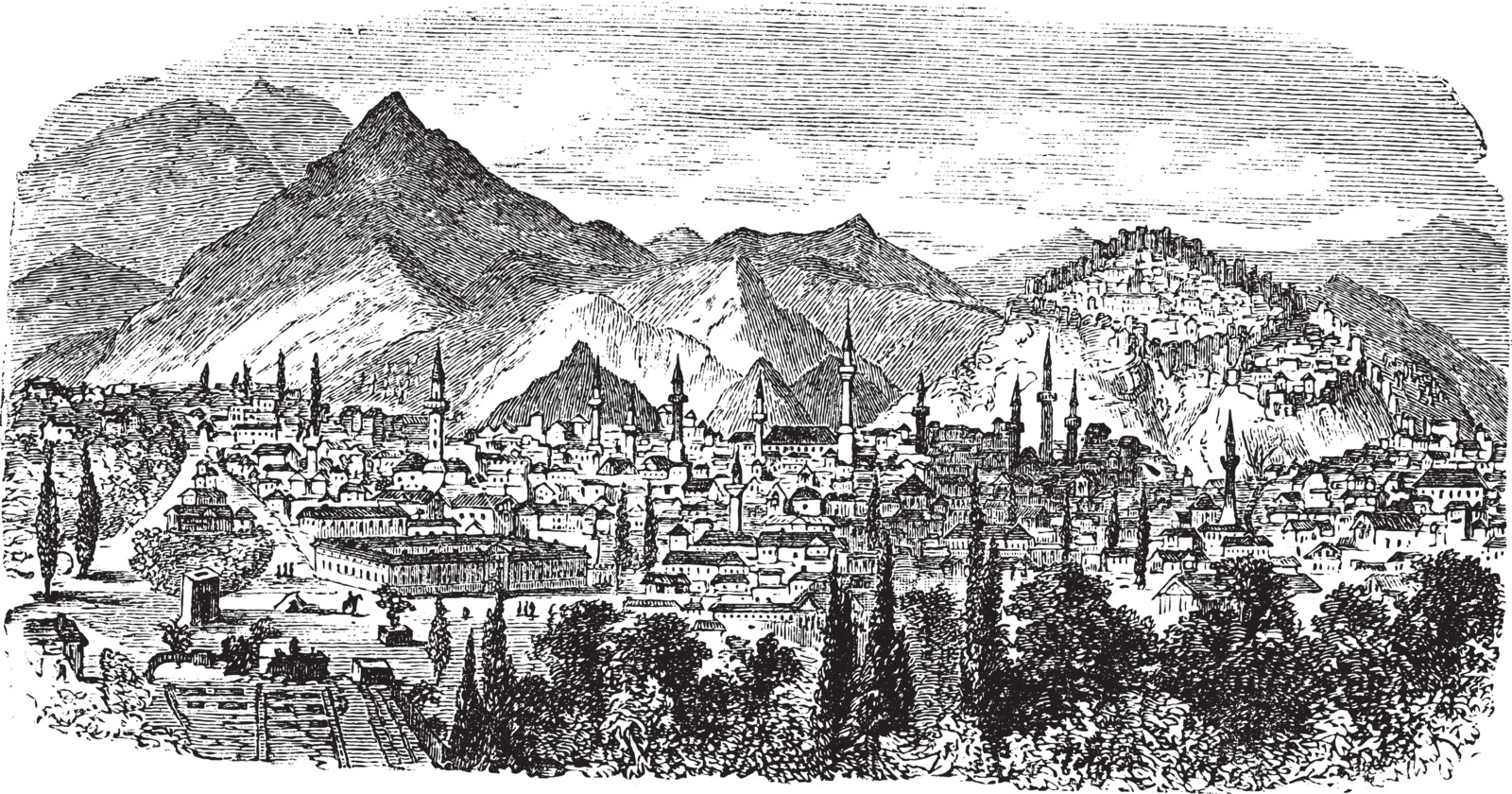

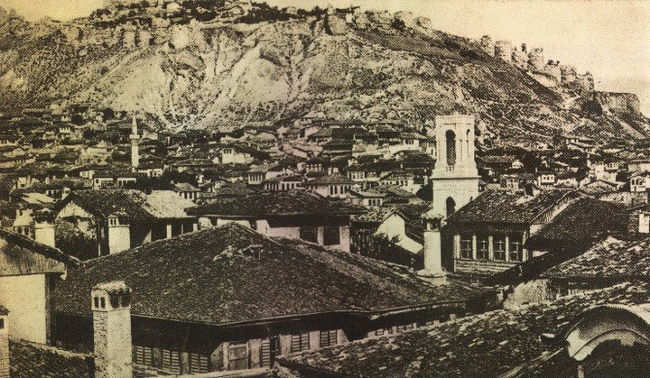

Kütahya City

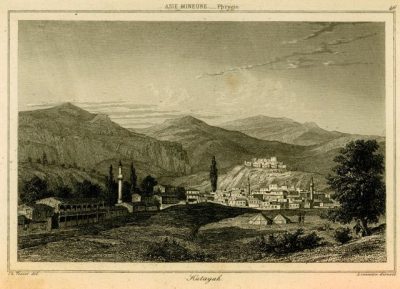

Kütahya (ancient Gr: Κοτυάειον Kotiaeion or Κοτύαιον – Kotiaion; Kotyaion; Ketaia; Ar: Kutina; Koutina), a city in the West of Asia Minor, lying on the banks of the Porsuk River, 969 meters above sea level, at the foot of Yellice Mountain (previously Acemdağı), looks back on five thousand years of history. The region has large areas of gentle slopes with agricultural land and the town that is overlooked by a fortress. Emperor Justinian I is believed to have first ordered the construction of the old city’s citadel and its double-lined walls.

Kütahya was under the control of Rome and Byzantium until the end of the 11th century when it was occupied by the Seljuk Turks in 1080. Thereafter, Kütahya became a border march between the Byzantine and Seljuk states. It changed hands several times before becoming the capitol of the Kurdish/Turkoman Germiyan principality in 1302. The city was finally absorbed into the Ottoman Empire upon Yakub’s II death in 1429. In 1453, the Ottomans made Kütahya the seat of a beylerbey (governor-generalship).

Population

“The Armenian presence in Kutahia is believed to date to the Byzantine era. Many more Armenians apparently settled there during the period of Seljuk domination. Their numbers grew in the fifteenth century, when a new wave of Armenian immigrants arrived from Agulis, near old Julfa along the Arax River. The influx continued in subsequent centuries.”(1)

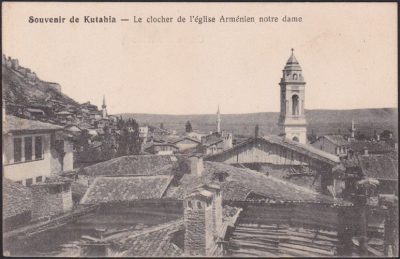

The Ottoman traveler and historian of Abkhaz origin, Evliya Çelebi (1611-83), took note of three Armenian and three Greek quarters when he visited Kütahya around 1670 and was fulsome in his praise for the quality of the tiles produced and used to decorate the town’s houses.(2) “At the end of the nineteenth century, Kütahya’s population was counted at 120,333, of which 4,050 were Greeks, 2,533 Armenians, 754 Catholics, and the remainder Muslims. The spiritual needs of the Armenian community were tended to by the respective bishops of the Apostolic and Catholic denominations. Each of these groups operated an elementary school and a secondary school. The town of Kutahia had two public libraries, four churches (including the Armenian Surb Astvatsatsin and Surb Toros), a hospital, pharmacies, public baths, and dozens of tanneries, workshops, stores, and retail shops. Other Armenian churches in the district were Surb Stepanos in the village of Davshanlu; Surb Lusavorich at Alinja; Surb Harutiun at Arslanik-Yayla; and Surb Khach (Holy Cross) at Viranjik.”(3)

Ottoman Center of Ceramics Manufacturing and Trade

After Nikaia (Iznik), Kütahya was Ottoman Turkey’s most important center of ceramic production. Industries of Kütahya have long tradition, going back to ancient times. Thanks to abundant deposits of clay in the area, ceramics were made here in large quantities in Phrygian, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine times and the traditional techniques of this art have survived to the present day. Kütahya’s commercial importance stemmed from its location on the great road which ran through Asia Minor from Istanbul to Aleppo, and from its emergence as a center for the production of glazed and multicolored ceramics and tiles, which were used to decorate mosques, churches, and synagogues throughout the Middle East and Europe.

Initially, Kütahya tiles featured traces of Byzantine and Seljukian cultures. Tiles with motifs of arabesques, lotus flowers, tulips, crowns, stylized leaf shapes and curved knots decorate walls of palaces, villas, mosques, baths. Famous buildings are among them like the Blue Mosque and the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, the Dome of the Rock and the St James Cathedral in Jerusalem and the Mevlana Monastery in Konya. Pottery was the city’s export hit.

The production of painted ceramic wares and tiles had begun in Kütahya by the end of the 1400 or perhaps much earlier. The earliest dated Kütahya tiles are the monochrome glazed bricks on the balcony the Kurşunlu Kasımpaşa Mosque in Kütahya (1377). During the early Ottoman and pre-Ottoman Turkish periods the Kütahya’s pottery industry essentially paralleled that of Iznik. In the 17th century Kütahya began to supplant Iznik as the center of the production of ceramic vessels and tiles in the Ottoman Empire.

When Sultan Selim I won a victory against Iranians in Çaldıran in 1514, some tile makers from Tabriz were resettled in Kütahya while others were placed in Nikaia (İznik). This marked the beginning of a tile manufacturing competition between the two cities that would last for 200 years. The tile makers brought with them from their Persian homeland the art of faience production and found ideal conditions: the hard, white clay of the Kütahya area was of outstanding quality. Various shades of blue and turquoise under a transparent glaze on a white background, reminiscent of Chinese ceramics from the Yüan and Ming periods, became the trademark. The craftsmen made the blue from cobalt oxide, turquoise and green from copper oxide. The workshops of Nikaia (Iznik) and Kütahya developed under glass painting to perfection.

The Ottoman capital Constantinople preferred tiles manufactured in Nikaia. During the XVI century, while ceramics from Iznik were considered Court Art and number one, Kütahya was thought to only produce popular middle-class ware, mostly for and by the Armenians, Greeks and other Christian minorities.

Lying outside of court influence, Kütahya’s ceramics remained unnoticed, overshadowed by the brilliant pottery of Iznik. However, from the 18th century (while the pottery of Iznik has been finally decayed), Kütahya wares largely reflected the tastes of folk art, introducing the pictorial decoration in the form of scenes and figures from daily life. Relied on the free market for a living, the potters of Kütahya began to use new forms, patterns and colors, succeeding for a short while to produce ceramics for the world market. According to scholar Hülya Bilgi “…the most important novelty, in Kütahya tiles and ceramics, which makes them particularly distinct from those made in Iznik, was the use of bright yellow as of the beginning of the 18th century. Towards the middle of the century, the range of colors used expanded with the addition of manganese purple and its increasingly dark tones. Embellishments came to include medallions in the form of serrated leaves and small free-style stylized floral bouquets, generally covering the entire surface …”.[4]

Subsequently, after the golden age of Iznik ceramics in the 16th century, Kütahya became the dominant producer of the Ottoman Empire, both for household wares and architectural tiles. During the 18th century, it acquired fine quality and thousands of wall tiles were produced to decorate several important buildings both private and public, inside and outside the Ottoman Empire.

Ceramics of Kütahya are characterized by a wide variety in decorative styles, heavily influenced by Chinese, Iranian and European pottery, as well as by the Ottoman tradition. Stylized floral motifs, motifs with Christian and religious themes, as well as human and animal figures decorate most of the 18th century Kütahya’s tiles and ceramics. The pieces dating from this period have a white or cream-colored paste, white slip and transparent glaze. The motifs are painted underglaze in green, turquoise and yellow, cobalt blue and, from the mid-18th century onwards, manganese purple, with motifs being outlined in black. A second group of Kütahya wares consisting of dishes, lemon squeezer, bowls, bottles, plates and cups dating from the 18th century are decorated with stylized flowers, leaves and curling tendrils in cobalt blue, with the occasional addition of yellow, green or turquoise. Ewers and jugs of various shapes and sizes are decorated with cypress tree motifs in relief, circular crosshatched medallions and floral scrolls worked in free brushstrokes.

After such a flourishing century, Kütahya’s production started to decline during the XIX century. Today’s Kütahya tiles are thought to be not matching those of Ottoman times in terms of fine taste and minimalist aesthetics. The reason for that is thought to be the fact that the mystery of color mixes of those times remains unrevealed.

The ceramicists

The Kütahya craftsmen who made tableware were known as fincanci (cup makers). Consequently Muslim and Christian potters work together in Kütahya producing objects designed to meet the needs of both communities. Most of the Christians craftsmen of Kütahya were Armenians who played a particularly important role in the history of town’s pottery. There were also Christian potters of Greek origin. That is the reason for the numerous Christian themes (many of them with inscriptions in Armenian or Greek) depicting saints, angels, scenes from the New and Old Testament, motifs relating to the Christian liturgy and hanging ornaments (egg-shaped or spherical) with crosses and seraphims.

Apreham (Abraham) of Kütahya is the most known Armenian craftsman, due to a small ewer he decorated in the 16th century. The ewer with bulbous body is painted in shades of blue and cobalt with a tall spout rising above the level of the rim and a handle in the shape of an open-mouthed dragon. This object is today in the British Museum in London and has an inscription on the base. Writing in Armenian, the Christian craftsman gives his name – Abraham of Kütahya – and the year AH 959 (AD 1510). This is one of the oldest examples of Kütahya pottery.

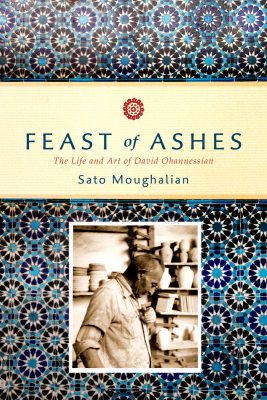

Although most Armenians in the mutessarifat Kütahya were spared from the WW1 genocide, most of them left nevertheless, and in 1922 the Kemalists drove out the ones who had stayed. The craft industry of Armenian ceramics in Jerusalem was started by Armenian ceramicist David Ohannessian (1884-1953), master of a Kütahya workshop between 1907 and 1015, who was arrested and deported from Kütahya during the Ottoman genocide in early 1916, but rediscovered, living as a refugee in Aleppo in 1918, from where he and his family moved to Jerusalem when Sir Mark Sykes, a former patron, who connected Ohannessian to the new Military Governor of Jerusalem, Sir Ronald Storrs and arranged for Ohannessian to travel to Jerusalem to participate in a planned British restoration of the Dome of the Rock. Sykes suggested that Ohannessian might be able to replicate the broken and missing tiles on the Dome of the Rock, a building then in a decayed and neglected condition. Although the commission for the Dome of the Rock did not come through, the Ohannession pottery in Jerusalem succeeded, as did other Armenian potteries in Jerusalem, beginning in the 1920s. Uprooted, the famous Armenian ceramicist Ohannesian spent his last years in Cairo and Beirut.(5)

In 1922, after the disastrous ending of the Greek campaign in Ottoman Asia, many Greeks and Armenian craftsmen moved to Greece as refugees. Among them, Minas Avramidis (1877-1954) and Makarios Vardaksis (Vardaxis, 1885-1950) master potters from Kütahya. After many difficulties, they established their own potteries in Thessaloniki, producing Kütahya style ceramics and impacting with their creative power the local traditional pottery.

In Neon Faliron near Athens, Minas Pesmatzoglou (a refugee from Sparta, Asia Minor), founded in 1923 a pottery factory called «ΚΙΟΥΤΑΧΕΙΑ» (Kütahya), in which many Greek and Armenian craftsmen from Kütahya were employed (among them Minas Avramidis from 1923 to 1925). Decorative motifs of Iznik and late Kütahya’s period were reproduced on the ceramics of this factory.

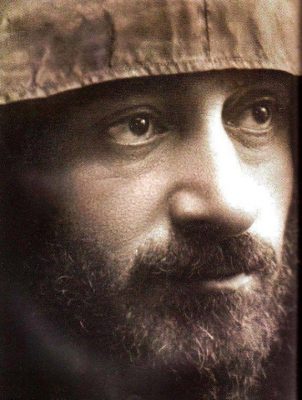

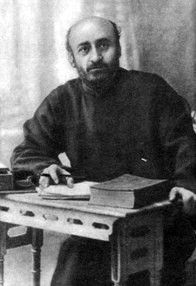

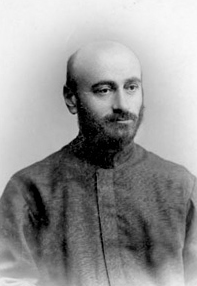

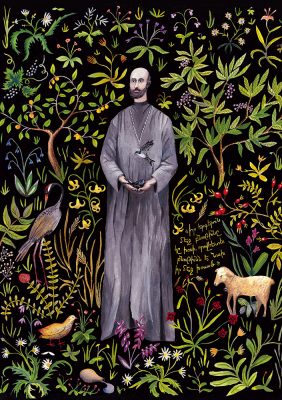

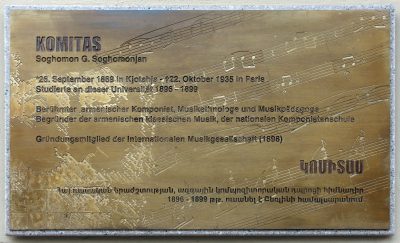

The most prominent koutinahay: Komitas Vardapet (Կոմիտաս Վարդապետ, i.e. Soghomon Soghomonian)

He was born as Soghomon Soghomonian on September 26,  1869 in the West Anatolian town of Kutina (Gr: Kotyaion, Ketaia; Tr: Kütahya) as the son of a music-loving Armenian shoemaker and his wife, the weaver Takuhi. Already orphaned at the age of eleven, he was known in his hometown for his beautiful baritone voice. In 1881, at the request of the Catholicos of all Armenians, he was brought to Echmiadzin, where he was to study in the local theological seminary together with

1869 in the West Anatolian town of Kutina (Gr: Kotyaion, Ketaia; Tr: Kütahya) as the son of a music-loving Armenian shoemaker and his wife, the weaver Takuhi. Already orphaned at the age of eleven, he was known in his hometown for his beautiful baritone voice. In 1881, at the request of the Catholicos of all Armenians, he was brought to Echmiadzin, where he was to study in the local theological seminary together with  twenty other selected orphans.

twenty other selected orphans.

There he also learned Armenian, because Komitas came from an area of the Ottoman Empire where the Armenians had been linguistically Turkified due to a particularly restrictive language suppression.(6) In 1895, Catholicos Khrimian Hayrig ordained Soghomon—now Komitas Vartabed—a celibate priest. He took the spiritual name Komitas in honour of the eponymous Catholicos and poet of spiritual hymns (sharakaner) from the 7th century. He taught music in Echmiadzin, founded a choir and an ensemble for folk instruments and undertook first researches on Armenian church music. Since autumn 1895 Komitas began to study music abroad (Tiflis/Georgia, at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he studied European composition). In 1896, under the protection of the Catholicos and with the support of the biggest Armenian oil magnate, Alexander Mantashian (Mantashev), he began to study music at the private conservatory of Prof. Richard Schmidt in Berlin and studied musicology, philosophy, theology, aesthetics and general history at the  Friedrich Wilhelm University until 1899. In September 1899 Komitas returned to Echmiadzin and continued his teaching activities at the seminary there. He visited various parts of Armenia and recorded thousands of Armenian, Kurdish and Persian folk tunes, studied Armenian hymns and began to decipher the old Armenian system of notation (‘khazer’). In 1910, he moved to Constantinople and rented a townhouse with the painter Panos Terlemezian. That house became a cultural center. Komitas taught music, refined and composed church music, held concerts in Kütahya, Constantinople, Izmir, Alexandria, and Paris, and received rave reviews. He continued to visit Germany, Paris, and other European cities, where he lectured and attended conferences of the International Music Society, as a founding member of

Friedrich Wilhelm University until 1899. In September 1899 Komitas returned to Echmiadzin and continued his teaching activities at the seminary there. He visited various parts of Armenia and recorded thousands of Armenian, Kurdish and Persian folk tunes, studied Armenian hymns and began to decipher the old Armenian system of notation (‘khazer’). In 1910, he moved to Constantinople and rented a townhouse with the painter Panos Terlemezian. That house became a cultural center. Komitas taught music, refined and composed church music, held concerts in Kütahya, Constantinople, Izmir, Alexandria, and Paris, and received rave reviews. He continued to visit Germany, Paris, and other European cities, where he lectured and attended conferences of the International Music Society, as a founding member of  the Berlin branch.(7)

the Berlin branch.(7)

His outstanding position in Armenian music history is comparable to Belá Bartók’s for the Hungarian, Antonín Dvořák’s for Czech or Edvard Grieg’s for the Norwegian music. He collected and processed folk tunes, but also studied the music of neighbouring peoples, including the Kurds. Komitas also maintained close contacts with Turkish artists. On April 2 and 3, 1915, shortly before his arrest, he gave lectures in a Turkish cultural centre in Constantinople-Beyazit. His strong interest in secular music inevitably led to conflict with the church leadership. In 1910 Komitas left Echmiadzin and settled in Constantinople, where he hoped in vain for more understanding for his projects. After all, he founded a mixed choir of 300 men and women there, which he called Gusan (‘bard’), and composed his masterpiece, a mass written for male choir (Armenian: Patarag). With similar choir formations in other large Armenian communities, Komitas contributed significantly to the popularization of Armenian classical music.

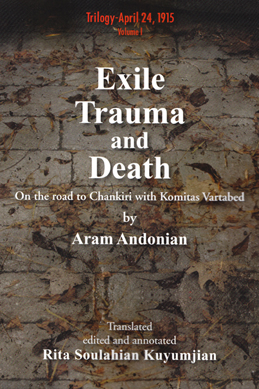

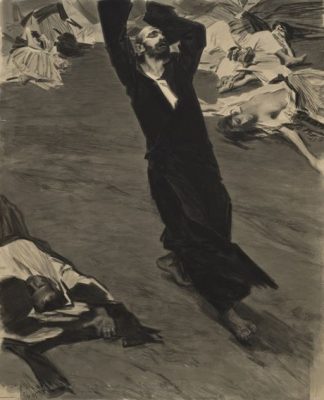

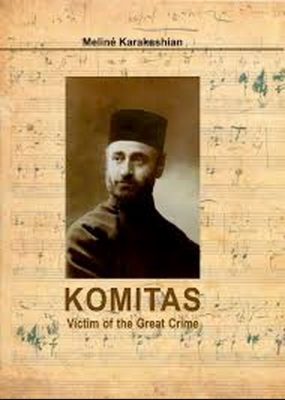

At the end of April 1915 (old style, i.e. according to the Rumi calendar) Komitas was arrested, along with over 2000 other Armenians, including hundreds of prominent intellectuals, and deported to the prison camp Çankırı on charges of high treason in Ankara province. When the constructed accusations could not be upheld in court, most of the prisoners were taken further inland and tortured and murdered during interrogations.

Komitas was one of the few survivors of the elite who had been arrested and deported since April 24, 1915. Thanks to international advocacy, especially from Germany, he was released. His name is among those few eight Armenians whose pardon was personally ordered by Interior Minister Mehmet Talat in a telegram dated May 7, 1915. But the deprivations and horrors of internment, the loss of his students, who had also been deported and murdered, as well as his valuable notes and research work, and finally the entire uncertainty of the situation had already shattered Komitas’ nerves. His apartment was located not far from the Constantinople police headquarters, where Armenians were tortured and killed. On Palm Sunday in 1916, when many Armenians from Constantinople had come to the service to hear their beloved Komitas celebrating mass, the physically weakened and emotionally challenged Vardapet collapsed over the altar in the most moving moment of the Armenian liturgy of Mass, the ‘Lord, have mercy on us’. For this was also the anniversary on which he had celebrated Mass for his fellow prisoners in Çankırı and for the Armenians of the surrounding villages.

“He could not teach music, earn a living. When his landlord threatened eviction if he did not pay rent, Komitas’s friends wrongfully decided to place him in the La Paix Turkish military psychiatric hospital, emptied his house, and returned it to the landlord. His 4,000 musical notes and personal items were dispersed, lost; only a third have been retrieved.

At the La Paix Turkish hospital, he complained that he was being given inferior food, that he had found pieces of rope in his soup, and devoured the bread and chocolate his students brought him. The Turkish chief neurologist and psychiatrist received honors for his studies of eugenics and overseeing the castration of mental patients. Komitas remained suspicious and uncooperative. He seems to have been discharged briefly in 1917, but was re-hospitalized. In 1919, his friends, seeing no progress, transferred him to a psychiatric hospital in Paris where a caretaking committee continued to provide the funds for his hospitalization. Since his ‘mental illness’ was not cured, in 1922 he was transferred to an asylum outside of Paris, to Ville Juif, where he would die years later from a foot infection. The French psychiatrist who knew Komitas for 13 years wrote that he was not sure what diagnosis had been given, to legally keep him in the hospital and asylum.”(8)

The highly talented musician never regained his creative power and died in deep depression and poverty on October 22, 1935 in a psychiatric hospital in the Parisian suburb of Ville Jouif. His symptoms were not recognised by contemporary medics as something that was only recognised as post-traumatic stress after the mass experiences of the victims of the Shoah and the Vietnam War.

Further reading: http://www.komitas.am/eng/index_eng.php

Komitas

ILLUSION

My soul is a butterfly

Fluttering up and down

Over seas of hope,My soul is a burden

Motherless, lovelorn

Panting in winds of light…

LOVEBREEZE

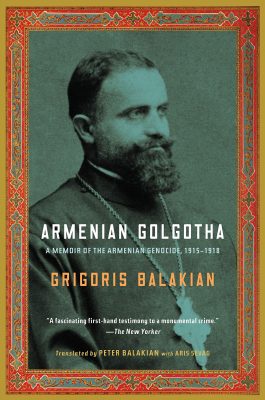

Grigoris Balakian: On the Way to Çankırı

“(…) The more we moved away from civilization, the more agitated were our souls and the more our minds were racked with fear. We thought we saw bandits behind every boulder; the hammocks or cradles hanging from every tree seemed like gallows ropes. The expert on Armenian peasant songs, the peerless archimandrite Father Komitas, who was in our carriage, seemed mentally unstable. He thought the trees were bandits on the attack and continually hid his head under the hem of my overcoat, like a fearful partridge. He begged me to say a blessing for him (‘The Savior’) in the hope that it would calm him. Elsewhere another acquaintance, an elderly lawyer, gave his gold watch and money to the carriage driver, asking him to deliver them to his wife as a remembrance upon his return to Constantinople.

Our carriages rolled along at reckless speed, to the ceaseless crack of the coachman’s whip and the curses of the police soldiers. Many times our comrades, unable to endure the jolts on the hard planks caused by the breakneck speed, fell out, barely to escape being run over.

It was forbidden for the carriages to stop, even for the most urgent of needs. Without bread, without water, our bones throbbing in pain, we advanced as if enemies were in pursuit, but of course they had already caught us. (…)”

Source: Grigoris Balakian: Armenian Golgotha: A Memoir of the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1916. Translated by Peter Balakian with Aris Sevag. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009, p. 66f.