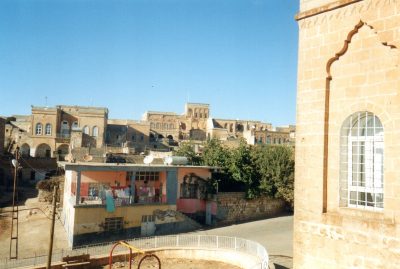

Midyat Town

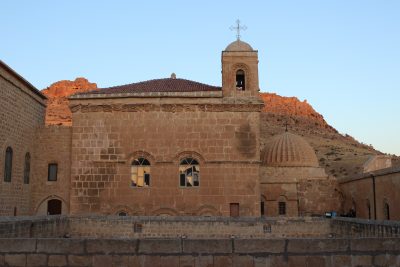

Located in the center of the sancak Mardin, Midyat (Aramaic ܡܕܝܕ Mëḏyaḏ; Kurdish Midyad or Midyade) forms the urban and administrative center of the Tur Abdin landscape. The city was the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Bishop from 1478 to 2009, who has since resided at the Mor Gabriel Monastery.

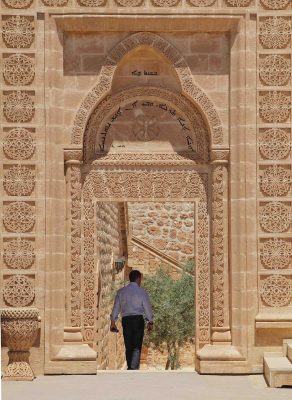

Midyat „is situated in the middle of a beautiful plain, surrounded by mountain slopes and hills”, wrote the French geographer Vital Cuinet in the late 19th century.[1] “There were at least six churches and two important monasteries in the vicinity, Mar Abraham [Mor Abrohom] and Mar Sharbel. Midyat was one of the symbols of the progress Christians had made thanks to the missionaries’ arrival. Whereas Taylor, in the middle of the 19th century, found nothing there but ‘a group of miserable hovels made of rough-hewn stone’, in 1906, Captain Mark Sykes was struck by the city’s prosperity and its beautifully decorated homes built with freestone, which even today gives the city its charme.”[2]

Toponym

It is possible that Midyat was the capital city of the Matiênê country, mentioned in an inscription of Assyrian king Aššur-nâṣir-apli I in 1043 B.C. In the 6th century B.C. it is mentioned as Matiati and Hekataios.[3] According to other sources the place name means ‘mirror’, which after many changes was formed from a mixture of Persian, Arabic and Aramaic. Another theory derives Midyat from the ancient Assyrian word ‘matiate’ (city of caves). This is suggested by an inscription on Assyrian tablets, which was created under King Aššur-nâṣir-apli II (ruled 883-859 B.C.). A third interpretation gives the word ‘matiate’ as Aramaic for ‘my neighborhood’ or ‘my homeland’.

Population

“When [Reverend George Percy] Badger visited [Midyat] in 1842, the city was still inhabited exclusively by Syriacs. The city’s climate seemed welcoming to him, despite the hidden struggle he could feel brewing with the neighboring Kurds.”[4] “(…) it is possible, that during the last quarter of the 19th century, an immigration of the Christian population into Midyat took place. According to several sources of information, the city’s Syriac population was constantly increasing. Badger gave the number of 450 ‘Jacobite’ families, or about 2,500 individuals. Following the 1882-1883 [Ottoman] statistics, K. Karpat said that there were 3,657 Syriacs living in the entire Midyat kaza (it is extremely unlikely that the kaza’s villages were counted), and finally Father Galland in 1889 did not hesitate to speak of ‘5,000 and more Jacobites who have remained attached to their schism’. Before the First World War, [the Chaldean] Father [Joseph] Tfinkdji counted 8,000 inhabitants for the city, of whom 6,000 were ‘Jacobites’. 450 Protestants (possible converted Syriacs), 100 Chaldeans and 1,300 Muslims, mostly Kurds. At almost the same time, S. Henno counted 1,400 Syriac households, which would make up o population of 8,400-9,800 individuals.

Such an increase in population was completely possible. Midyat experienced rapid economic expansion from the 1870s on, and had become attractive enough to appeal to the Tur Abdin Syriac population who were forced to abandon their land and villages.”[5]

In 1913, the Syriac Catholic scholar Isaac Armalet (Syriac: ܐܝܣܚܩ ܒܪ ܐܪܡܠܬܐ ʼIsḥoq Bar ʼArmalto, 1879-1954) reported in his travelogue that between 6,000 and 7,000 people lived in Midyat. The majority were Syriac-Orthodox Christians, plus 80 Protestant families, 30 Syriac-Catholic, Chaldean and Armenian, plus 50 Muslim families. According to the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople, 1,452 Armenians lived in the town of Midyat before the First World War.[6] They maintained a church and two schools for 210 students. According to the 1960 population census Midyat was home to 570 Christian households and only 30 Muslim households.[7]

History

The history of Midyat can be traced back to the Hurrians during the 3rd millennium B.C.. Midyat is already mentioned in writing in the Assyrian annals in the 13th century B.C. by the Assyrian king Aššur-nâṣir-apli I: “I have subjugated Matiate (= Midyat) and its villages; I took rich booty from there and imposed tribute and heavy taxes on them”.

In the 6th century B.C., Midyat belonged to the Achaemenid Empire; in 330 B.C., it was conquered by Alexander the Great. In 320 B.C. it belonged to the Seleucid Empire until the 2nd century B.C. After that it was the border region of the Parthian Empire and from 193 on, as the province of Mesopotamia, part of the Roman Empire. According to later traditions, the inhabitants are said to have been converted to Christianity by the apostles Thomas and Thaddeus as early as the 1st century.

In 640 the Arabs under the Umayyads replaced the Byzantine Empire. 750 the Abbasids took over power. At the height of the Abbasid caliphate, under Caliph Harun ar-Rashid, Midyat and its surroundings underwent a major reconstruction of entire villages and buildings. In 1101, the area fell to the Seljuks under the Artuqid (Ortoqid) dynasty. Muin ad-Din Sökmen I also ruled over Midyat as Emir of Mardin. His successors ruled until 1409, when the Artuqid line died out. In 1402 the Mongols under Timur marched on their way to Ankara, plundering through the Tur Abdin. Between 1235 and 1243, the Seljuqs lost the area to the Mongols and the Artuqids became vassals of the Ilkhane. The successor of the Artuqids was the Turkmen tribal mess-federation Ak Koyunlu (‘white mutton’). In 1451, the Kara Koyunlu (‘black mutton’), the arch-enemies of the Ak Koyunlu, conquered Mardin and the surrounding area, including Midyat.

In 1478 Midyat became the bishopric of the Syriac Orthodox Church. In 1507, the Shah of Persia, Ismail I, conquered Midyat and Mardin, but had to withdraw from Anatolia as early as 1514 after losing the battle of Çaldiran against the Ottomans under Sultan Selim I. Since then, the Ottomans, who were replaced by the Republic of Turkey in 1923, have ruled.

In 1810, the kaza Midyat was formed, and in 1890 the town was elevated to the status of a city. Due to the discrimination of the Christian population (among other things prohibition of weapons, tax burden up to 60%) and the numerous plunderings by Mongolians, Turkish as well as Kurdish tribes in the Tur Abdin plateau, which reached their peak at the end of the 14th, 19th and beginning of the 20th century with massacres in the course of the genocide of 1915, the Christian population was decimated strongly.

In 1855 the Kurdish leader Êzdan Şêr ravaged Tur Abdin, burned the crops and robbed Aramaic women and children as slaves. The Kurdish raids continued until 1877, when the sons of the Kurdish leader Badr (Bedir) Khan (Bedirxan) conquered the cities of Mardin, Midyat and Nusaybin and proclaimed a Kurdish emirate. Only eight months later an Ottoman army together with the Aramaeans succeeded in defeating and driving out the Kurds. After the Ottoman massacres of Armenians and Syriacs from 1895 and 1896 (the so-called Hamidic massacres), repression against the non-Muslim population of Midyat intensified under Sultan Abdülhamid II. In order to control the non-Muslim areas in southeast Anatolia, Abdülhamid II set up an army of Kurdish volunteer units, the Hamidiye Alaylari (Hamidiye Cavalry). As this force was only under the control of the Sultan, it could harass the Christian population of the area indiscriminately and with impunity.

In July 1914, the Ottoman government decided to mobilize them. All Christian men in Midyat between 20 and 45 years old were taken away in chains to serve the army in building roads. None returned. On 6 July 1915, Kurdish cavalry units and the regular army attacked Midyat, murdering women and children and plundering the city. Only a few Christians found refuge in the neighboring Arab countries, mainly in Syria and Lebanon. After 1930 the city was rebuilt with houses and churches. The number of Christian inhabitants increased slightly.

Destruction

In an estimate presented at the Paris Peace Conference (1919), the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate put the number of massacred Syriac Orthodox Christians in the kaza Midyat at 25,830 and the number of destroyed villages at 47.[8]

Habib Maqsi-Musa: Infanticide in Midyat

“My uncle Musa was six years old in the ‘Year of the Sword’ [Sayfo]. As a boy, I heard his story about the Sayfo.

In the market of Midyat, there was a place called Shafqo, near the house of the [Protestant] Nateqo family. And there I observed Turkish soldiers killing little Christian boys. They threw the boys down [from the roof] from the high building so that they died immediately. Many Christian deportation convoys arrived in Midyat, and they consisted of women and children. These were taken to the courtyard of the mosque, which soon became crowded. To reduce the number of hostages, the Turkish forces gathered the boys, about 500-600 in number. They ordered them to lie face down. After that, they took some thick sticks and beat them on their heads. After that, 40 to 50 Turkish soldiers on horseback rode back and forth over the boys’ heads until they were dead.”

Account by Chaldean Habib Maqsi-Musa, b. 1948, interviewed August 2003; excerpted from: Gaunt, David: Massacres, Resistance, Protectors; Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia during World War I, 2006, p. 342.

Carl Friedrich Lehmann-Haupt: Matia(u)ti, the “City of Caves”

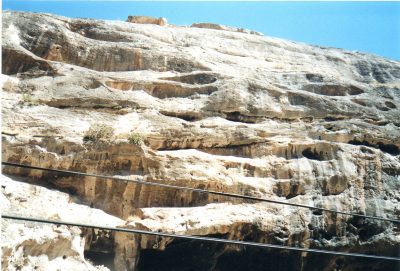

“Assurnassirabal III[9] [Ashur-nasir-pal II; Ašur-nāṣir-apli II] tells (…) in his annals that he conquered the city of Matia(u)ti ‘with its cave city’ – at least this is the most likely translation. While there were a large number of caves here, the old Matiati was found in Midyad, since its geographical location is approximately correct according to Assurnassirabal’s information.

My researches were successful. The rocky plateau on which the monastery ‘Der’ of Midyad is located, and which is almost directly adjacent to the city, shows on its steep slopes a number of partly very well worked cave rooms, whose entrances are often covered with earth up to the full height of the rocky slope. Further evidence of ancient times is provided by the stairs or step-like workings I noticed on the rock near one of these caves; further excavations would undoubtedly reveal many more of these cave rooms. Before the monastery was built, these ancient caves may have been used by Christian anachoretes, here as elsewhere, so that the neighborhood between the caves and the monastery (…) is more than a mere outward appearance.

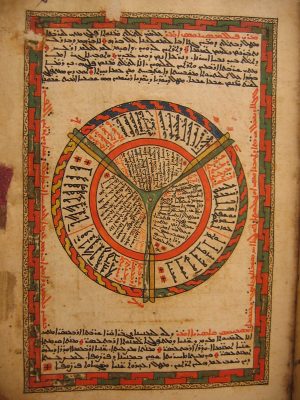

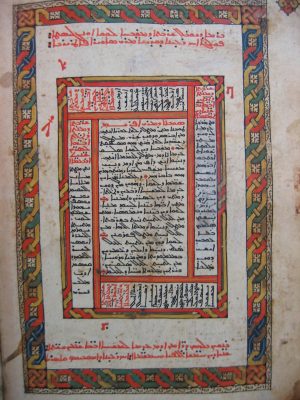

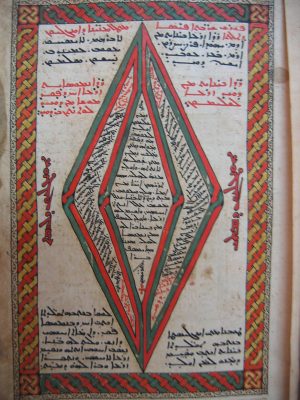

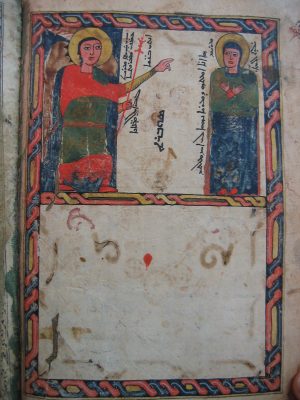

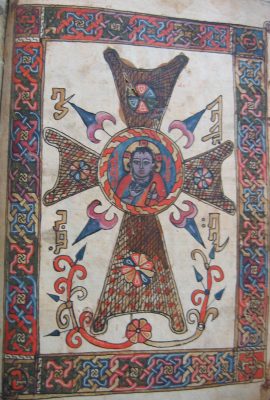

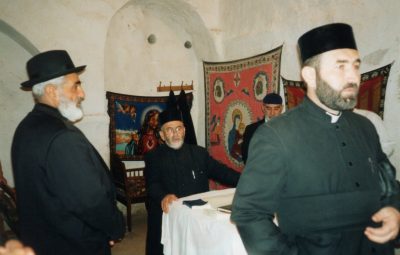

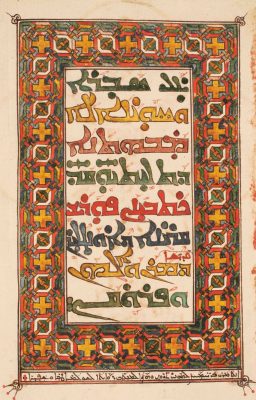

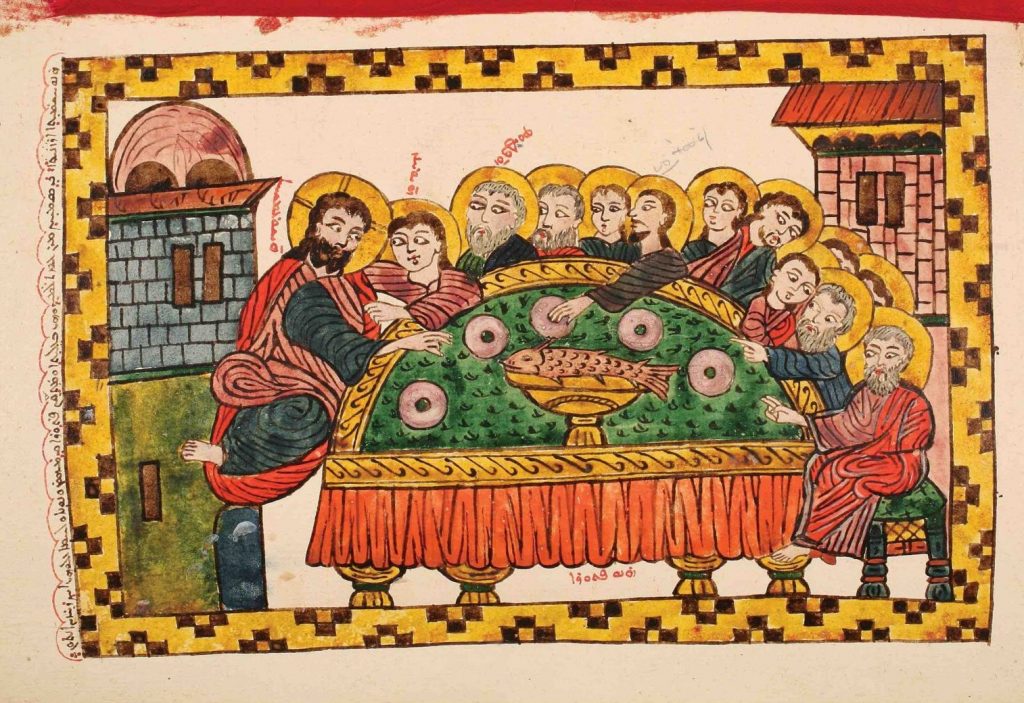

(…) When I returned the visit of the heads of the Jacobite clergy, I saw a number of interesting old manuscripts, including an old gospel book in a heavy wooden cover in beautiful Estrangeloscript (…), which dates back to the year 1200 since Alexander the Great, i.e. about 1000 years old. It was illustrated, the pictures protected by canvas. The manuscript came from the Monastery Mar Jaqūb (…).”

Excerpted from: Lehmann-Haupt, Carl Friedrich: Armenien Einst und Jetzt, Vol. 1: Vom Kaukasus zum Tigris und nach Tigranokerta (1910). Berlin: B. Behr’s Verlag, 1910, p. 370f.

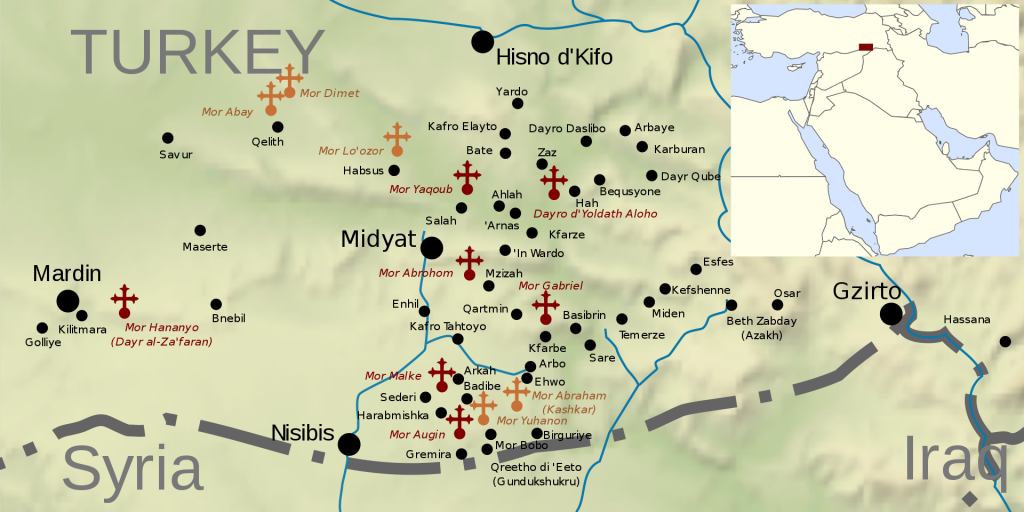

Map of Tur Abdin showing Syriac villages and monasteries. Operational monasteries are indicated by red crosses, and abandoned monasteries are indicated by orange crosses (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tur_Abdin#/media/File:Tur_Abdin.svg)

Tur Abdin

The landscape of Tur Abdin (Aramaic: mountain of the servants [of God]) is located in the southeast of today’s Turkey, north of Syria and northwest of Iraq. To the east of Tur Abdin is the city of Cizre, to the west the city of Mardin, to the south Dara and Nusaybin, to the north Siirt and B’sheriye. The west-east extension is about 200 km, the north-south extension about 150 km.

The Tur Abdin forms a plateau. At its borders (partly also in the interior) several mountain ranges are scattered, e.g. the so-called Mardin Mountains north of Mardin with an altitude up to 1300 m and north of Cizre the Judi (Trk.: Cudi Dağı; also Qardū, Aramaic: קרדו, Classical Syriac: ܩܪܕܘ) Mountain(s), which rise up to 1800 m. In the south, the high mountain range drops steeply and ruggedly to the Mesopotamian plateau. Tur Abdin consists almost entirely of limestone, often interspersed with marl layers. But the scree is also covered with sharp-edged basalt blocks of volcanic origin.

Tur Abdin is of great importance to the Syriac Orthodox, for whom the region used to be a monastic and cultural heartland. The Syriac community of Tur Abdin calls themselves Suryoye, and traditionally speak a central Neo-Aramaic dialect called Turoyo.

During the First World War, the Syriac population was exposed to two waves of attacks. The first took place at the beginning of summer 1915, at the same time as the events in Mardin and Diyarbekir. The villages Ma’asarte (800 inhabitants), Bafawȃ (600 inhabitants) and Al-Ibrahimiya (400 inhabitants) were completely wiped out at the end of June 1915, as was the village of Kelek, eight hours’ walk from Mardin, where all 2,000 Christians were killed.

A second wave of attacks followed in 1917, with some villages initially succeeding in defending themselves only to become main targets of the Ottoman army.[10] Especially well known is the self-defense of the villages Azakh (Hazakh, Idil), Iwardo (also In Wardo, Ayn Warda, Ain Wardo), and Basibrin.

About three thousand Christians were still living in Tur Abdin in 2014.

Julius Bittmann: In Tur Abdin, at the cradle of Christianity: The difficult situation of Christians in the East of Turkey (23 June 2001)

“In the very southeast of Turkey, between the Tigris in the north and east, Syria in the south and the city of Mardin in the west, lies the Tur Abdin. It is a hilly highland (800 to 1100 meters) of limestone and basalt rock. The main source of income is agriculture. The name Tur Abdin (‘mountain of the servants of God’) was given to the land with limited water resources by the about eighty monasteries, which are mostly located remote from the villages.

Tur Abdin is one of the oldest Christian areas where the language of Jesus, Aramaic, is still spoken as a colloquial language. The Christians there belong to the Syriac Orthodox tradition and derive from the early Christian community in Antioch, which was founded by St. Paul. From Antioch, today’s Antakya, the Gospel spread to the West and East. In the immediate vicinity of the Tur Abdin, in Edessa and Nisibin the two apostle disciples Addai and Mari are said to have preached.

The center of religious life in Tur Abdin is the Mar (Mor) Gabriel monastery. It was founded in 397 by the saints Samuel and Simeon and has been inhabited by monks ever since, except for two short periods when war and hunger made it impossible to stay. The monastery received numerous donations from the Eastern Roman emperors, for whom the fortress-like building not far from the border was a bulwark of the Roman Empire against the Persians. On the extensive fields the monks harvested fruit and vegetables, especially olives. St. Simeon [d. 734] himself had planted twelve thousand olive trees and therefore received the name ‘Simeon of the Olives’.

A hundred years ago, half a million Syriac Christians still lived in Tur Abdin, today their number has dropped to three thousand. In the final phase of the Ottoman Empire, Christians were also bloodily persecuted along with Armenians. Between 1926 and 1928, further mass executions and expulsions of Christians took place. And in the last decades the Christians of Tur Abdin were caught between all fronts in the fights between the Turkish military and the Kurdish PKK as well as Islamic fundamentalists and were wiped out. Many preferred to leave the country. Today there are about 40,000 Syriac Christians in Germany, 60,000 in Switzerland and Sweden, and about ten thousand in Istanbul.[11]

In Tur Abdin there are currently 32 villages with Christian inhabitants, seven monasteries are still inhabited, but only by very few monks or nuns, in 42 churches, which are looked after by 15 priests, services are still held. The human rights organization ‘Amnesty International‘ has repeatedly denounced attacks against Christians in Tur Abdin. In 1993, for example, the village of Zaz near Midyat was attacked and four Christian inhabitants were arrested and tortured. In June 1996, three Christians in Midyat experienced similar mistreatment or torture in police custody. A 60-year-old Syriac Orthodox priest was presumably kidnapped by village gunmen or by Islamic fundamentalists in January 1994 while on his way to a wedding ceremony. The district mayor of Midyat, Yakup Matte, and the last Christian doctor of Tur Abdin, Dr. Edward Tanriverdi, were murdered in 1994. In none of the cases of murder of Christians has any perpetrator ever been identified and brought to justice, which is why Christians in Tur Abdin feel defenselessly exposed to the attacks. Since 1980, a total of twenty girls have been abducted by Muslims in the surroundings of Diyarbakir and Mardin.” (…)

Tur Abdin: The Main Monasteries

The monasteries Mor Hananyo (Monastery of Saint Ananias; Trk.: Deyrüzzaferân Manastırı, Syriac: ܕܝܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܚܢܢܝܐ; Kurdish: Dêra Zehferanê; Saffron Monastery, Deir el-Zaferan) and Mor (Mar) Gabriel (Syriac: ܕܝܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܓܒܪܐܝܠ; Trk.: Deyrulumur Manastırı) are the most important of the region, existing along with six or seven other active monasteries.

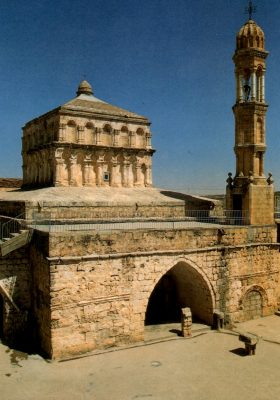

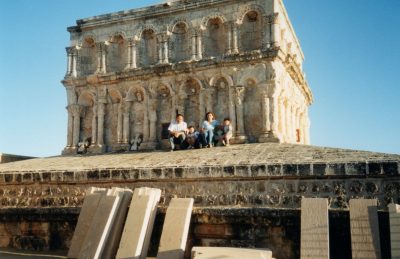

Dayro d-Mor (Mar) Hananyo –ܕܝܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܚܢܢܝܐ (Saffron Monastery)

The most important Syriac Orthodox center in Tur Abdin is the monastery of Dayro d-Mor Hananyo, just few kilometers south east of Mardin, in the west of Tur Abdin. Built from yellow rock, the Monastery is located on the site of a temple dedicated to the Mesopotamian sun god Shamash, which was then converted into a citadel by the Romans. After the Romans withdrew from the fortress, Mor Shlemon transformed it into a monastery in 493 AD. In 793 the monastery was renovated after a period of decline by the Bishop of Mardin and Kfartuta, Mor Hananyo, who gave the monastery its current name.

The monastery was later abandoned and re-founded by the bishop of Mardin, John, who carried out important renovations and moved the see of the Syriac Orthodox Church here before his death on 12 July 1165. From 1160 until 1923 it was the official seat of the patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church, after which it was moved first to Homs and in 1959 to Damascus. However, the Patriarchal throne and many relics are still located in the Monastery, as well as the tombs of various Patriarchs.

Today the monastery is led by a bishop and a monk and some lay assistants, and is a school for orphans. The bishop of Mor Hananyo is also the patriarchal vicar of Mardin. His goal is to rebuild the monastery and to preserve the history of the Syriac Orthodox church. The Dayro d-Mor Hananyo is part of the UNESCO world cultural heritage and was visited by numerous celebrities e.g. like Prince Charles (now King Charles III).

The monastery has 365 rooms – one for each day of the year. Services are held daily, led by one of the two remaining monks. To the right of the entrance, down a few steps is a prayer room originally used as a temple to Baal in 2000 B.C. Above it is an old mausoleum formerly used as a medical school; the wooden doors are inlaid with lions and serpents. The main chapel still retains patches of its original turquoise coat and houses a 300-year-old Bible, a 1000-year-old baptismal font, and a 1600-year-old mosaic floor.

Further Reading: http://syriacorthodoxresources.org/ChMon/MardinDKurkmo/index.html

William Dalrymple (1997): “A Remote Refuge”

“Until the First World War, Deir el-Zaferan was the headquarters of the Syrian Orthodox Church, the ancient Church of Antioch. The Syrian Orthodox split off from the Byzantine mainstream because they refused to accept the theological decisions of the Council of Chalcedon in 451 A.D. The divorce took place, however, along an already established linguistic fault-line, separating the Greek-speaking Byzantines of western Anatolia from those to the east who still spoke Aramaic, the language of Christ. Severely persecuted as heretical Monophysites by the Byzantine Emperors, the Syrian Orthodox Church hierarchy retreated into the inaccessible shelter of the barren hills of the Tur Abdin. There, far from the centres of power, three hundred Syrian Orthodox monasteries successfully maintained the ancient Antiochene liturgies in the original Aramaic. But remoteness led to marginalization, and the Church steadily dwindled both in numbers and in importance. By the end of the nineteenth century only 200,000 Suriani were left in the Middle East, most of them concentrated around the Patriarchal seat of Deir el-Zaferan.

The twentieth century proved as cataclysmic for the Suriani as it had been for the Armenians. During the First World War death throes of the Ottoman Empire, starvation, deportation and massacres decimated the already dwindling Suriani population. Then, in 1924, Atatürk decapitated the remnants of the community by expelling the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch: he took with him the ancient library of Deir el-Zaferan, and eventually settled with it in Damascus. Finally, in 1978, the Turkish authorities sealed the community’s fate by summarily closing the monastery’s Aramaic school.

From 200,000 in the last century, the size of the community fell to around seventy thousand by 1920. By 1990 there were barely four thousand Suriani left in the whole region; now there are around nine hundred, plus a dozen monks and nuns, spread over the five extant monasteries. One village with an astonishing seventeen churches now only has one inhabitant, its elderly priest. In Deir el-Zaferan two monks rattle around in the echoing expanse of sixth-century buildings, more caretakers of a religious relic than fragments of a living monastic community.”

Quoted from: Dalrymple, William: From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium. Hammersmith, London: Flamingo, 1997, p. 90f.

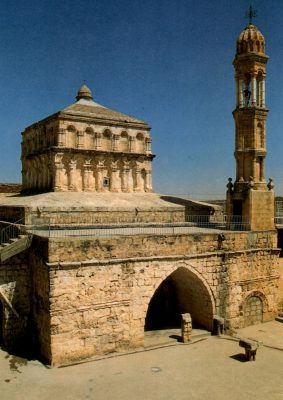

Dayro d-Mor (Mar) Gabriel – ܕܝܪܐ ܕܡܪܝ ܓܒܪܐܝܠ (Deyrulumur Manastırı)

In the center of the Tur Abdin region, 20 kilometers southeast of Midyat, is Dayro d-Mor Gabriel. Founded in 397 A.D. by the ascetic Mor Shmue’el (Samuel) and his student Mor Shem’un (Simon), Mor Gabriel is the oldest Syriac Orthodox church in the world. According to tradition, Shem’un had a dream in which an Angel commanded him to build a House of Prayer in a location marked with three large stone blocks. When Shem’un awoke, he took his teacher to the place and found the stone the angel had placed. At this spot Mor Gabriel Monastery was built.

The monastery’s importance grew and by the 6th century there were over 1000 local and Coptic monks there. The monastery became so famous that it received contributions from Roman Emperors, such as Arcadios, Honorios, Theodosios II and Anastasios. The dome of the monastery, erected at the beginning of the 6th century, is made of radially layered bricks and rests on walls of ashlar and mortar core. The inner diameter of the dome is 11.50 m. It is probably a foundation of the Roman Emperor Anastasius, who after 506 donated to numerous Christian churches and monasteries in this region.

Between 615 and 1049 the Episcopal seat of Tur Abdin was based here and from 1049 until 1915 the monastery had its own diocese. The monastery owes its name to one of the bishops, Mor Gabriel of Beth Qustan (in office from 634 to †667/8). It was named after him in the 7th century.

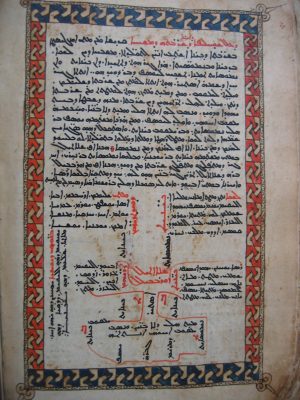

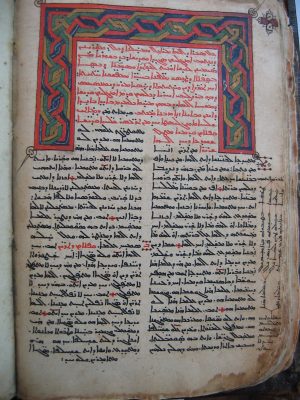

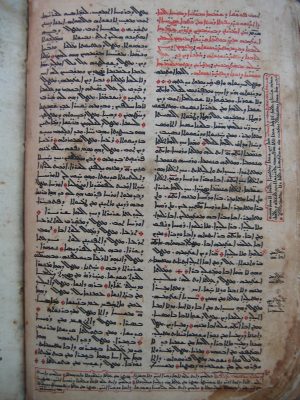

19th-c. Syriac liturgical-manuscript from Dayro-d-Mor Gabriel near Midyat (MGMT-52; source: http://hmml.org/about/global-operations/turkey/)

The monastery was an important center for the Syriac Christians of Tur Abdin. It maintained a highly important library, of which almost nothing remains today (some manuscripts are kept in the British Library, among other places); the monastic school played an important role in theological education in the region and in the whole Syriac church. It also educated many high-ranking clerics and scholars, including four patriarchs, a Catholicos and 84 bishops. Mor Philoxenos of Mabbug († 523) became widely known as prominent opponent of Chalcedonism. A quotation from him describes the importance of the monastery at that time: “Whoever visits the monastery founded by the angel seven times with honor and fear, acquires the same merit as if he were visiting Jerusalem.”

In the 7th century, the monastery became known as Monastery of St Gabriel, who was famous for his ascetic life. In the fourteenth century four hundred and forty monks were killed by invading Mongols. In 1991, the remains of monks killed by Timur (Tamerlane) were found in caves underneath the monastery, dated to the year 1401. 1915, during the Ottoman genocide the monks were massacred by Kurds and the monastery was occupied for four years until returned to the church in 1919. The fRench scholar Sébastien de Courtois summarized the genocidal events in the following way:

“The monastery of Mar Gabriel, where 70 inhabitants of the nearby village of Kfarbe had taken refuge, was attacked in the fall of 1917. All the monastery’s occupants were massacred together, with the monks and two priests. The bishopric as such had ceased to exist in 1915, when the last bishop, Philoxenos ‘Abd al-Ahad Misti from Kafra, abandoned the monastery. Only two young boys managed to run away to safety, one to the village of Bȃ Sabrinȃ, the other to Ain Wardo.”[12]

The monastery is an important center for the Syriac Christians of Tur Abdin with seven nuns and four monks occupying separate wings, as well as a fluctuating number of local lay workers, guests from overseas and around 40 students with their teachers. It maintained a significant library, however, almost nothing remains. The monastery is currently the seat of the metropolitan bishop of Tur Abdin. In its history the monastery has produced many high-ranking clerics and scholars, among them, four patriarchs, a Maphrian and 84 bishops.

Dayro d-Mor Gabriel is a working community set amongst gardens and orchards, and somewhat disfigured by 1960s residential accommodation. The monastery’s primary purpose is to keep Syriac Orthodox Christianity alive in the land of its birth by providing schooling, ordination of native-born monks. On occasions it has provided physical protection to the Christian population.

Dayro d-Mor Gabriel is open to visitors, and it is possible to stay with permission, but is closed after dark.

Legal disputes

In the last decades the monastery has been involved in a land dispute with the Turkish government and Kurdish village leaders, particularly those linked to the Çelebi tribe, backed by local representatives of the ruling Justice and Development Party. In 2008 the villages Eğlence, Çandarlı and Yayvantepe as well as the Turkish Land Registry and the Office Forestry Ministry filed legal proceeding disputing the territory of the monastery. The monastery won the legal dispute against the villages but lost to the Turkish authorities which resulted in a loss of territory ownership of 60%, which led the monastery to take the case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). On 10 May 2019, the ECHR has rejected a claim by the foundation of Mor Gabriel for the retransfer of church properties because of ‘missing documents’; the monastery’s foundation then announced further appeals. The transfer of all confiscated church property has not yet been completed. Many Suryoye fear that their millennia-old cultural heritage, churches and monasteries from early Christian times, will be sold or converted into mosques.

Turkish government assistance to the Kurds is seen as retaliation against the Syriac diaspora for lobbying for international recognition of the killings of tens of thousands of Syriacs during World War I as genocide. Their attempts to confiscate land owned by the monastery has garnered attention from many European governments and gathered opposition to Turkey’s EU bid, and could be the basis of a case by the monastery at the ECHR. Otmar Oehring from Missio, a German Catholic charity, has said that the cases mean that “the state’s actions suggest it wishes that the monastery no longer existed.”

There have also been claims that the monastery was built on the grounds of a previous mosque, regardless of the fact that the monastery was founded over 170 years prior to the birth of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

On 26 January 2011, the Turkish supreme court granted substantial parts of the Monastery to the Turkish Treasury. The ruling was that land inside and adjacent to the monastery, which the monastery has owned for decades and has paid taxes for, belongs to the State. On June 13, 2012 the Turkish supreme court of appeals upheld this decision, which Syriacs continued to protest.

The then Turkish prime minister Erdoğan announced on 30 September 2013 that the land would be returned to the Syriac community in Turkey. This decision was approved a week later (7 October) by the Prime Ministry Directorate General of Foundations. A land registration process of two months would begin and was subject to approval.

The head of the Monastery of Mor Gabriel Foundation was handed the deeds of 12 parcels of the immovable property belonged to the Foundation of the Monastery of Mor Gabriel on 25 February 2014. This was based on the decision taken on 7 October 2013 by the Council of Foundations of the General Directorate of the Foundations. The legal process for taking the remaining 18 parcels of the monastery property continues.

A news report in June 2018 stated that the Turkish Parliament had passed an omnibus bill which was then signed into law by the President to return historic Syriac properties. The government returned the title deeds which had been confiscated from Mor Gabriel Monastery.

Further Reading: http://syriacorthodoxresources.org/ChMon/MidyatDGabriel/index.html