The region surrounding Sinop produced abundant agricultural products including wheat, corn, barley, legumes and fruit (especially pears). Apart from working in these fields, its residents were also good fishermen, ship builders and trade merchants.

Administration

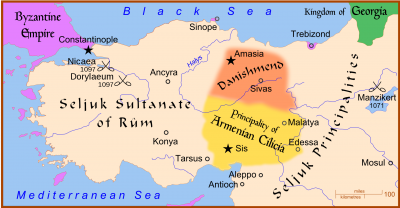

Sinop was annexed by the Ottoman State when the Jandarid (Candarid) principality was ended during the rule of Mehmed the Conqueror (May 1461). After it came under Ottoman domination, it was made a kaza (district) in the sancak of Kastamonu. Changes in the administration took place in later years. The sancaks belonged to larger administrative units, the eyalets, and Sinop was attached to the eyalet of Ankara and then to the eyalet of Bolu (Inebolu) between the years of 1840 and 1846, only to be subsequently re-attached to what became the Eyalet of Kastamonu.

In the period following the Tanzimat reform, Sinop was a sancak of Kastamonu, a vilayet in the north of Anatolia comprising the kazas of central Sinop, Boyabat and İstefan (Ayancık), and the nahiye of Gerze; the kaza of Boyabat included the nahiye of Durağan while the kaza of Ayancık included the nahiye of Çanlı.Including the central neighborhoods, Sinop consisted of one hundred and forty-four villages.[1]

Toponym

A myth associates the place name with that of the nymph Sinope, daughter of the river God Aesop (Grk: Ασωπού). According to another legend, Sinope was founded by the Amazons, who named it for their queen, Sinova.[2]

Konstantinos Fotiadis: The Greek Colonization of Pontos

“Greeks were present in the area from antiquity. Having conquered the shores of the Aegean from the Bronze Age, Greek seafarers dared to venture into the ‘man-eating’ waters of the Black Sea in their improved seagoing vessels, exploring its inaccessible beaches and mountain ranges. Researchers estimate that the first commercial voyages to the region began circa 1000 BCE, chiefly in search of gold and other ores. Jason’s organized mission to Colchis with the Argonauts, Orestes’ wanderings in Thoania, Odysseus’ adventures in the land of the Cimmerians, Prometheus’ exile to the Caucasus at Zeus’ command, Herakles’ journey to Pontos, and other seductive Greek myths that refer to this geographical region, confirm the existence of these most ancient of trade routes.

Two centuries later, these temporary trading posts had been transformed into permanent residential centres. Miletos was the first city to colonize Pontos, founding Sinope on a site which a fine harbours and unfettered communication with the surrounding area rendered especially advantageous. In its turn, Sinope founded Trebizond [Trk.: Trabzon] in 756 BCE, followed by Kromna, Pterion, Kytoros [Ordu] and other cities. Trapezounta remained a vassal state of Sinope, the metropolis, of its own volition until the time of Xenophon. For the first few centuries, the colonies remained copies of their respective metropolises. The Greek populations respectfully observed the traditions, mores, customs, building styles and deities they had brought with them from the metropolis. The cities remained on good terms, helping one another and multiplying, establishing new colonies in coastal regions, but also in the hinterland, close to waterways and usually at either the beginning or the end of a road.“[3]

Population

According to the 1871 Kastamonu yearbook a total of 2,955 Greeks lived in the sancak of Sinop, of these 2,545 in the kaza of Sinop. In addition, a total of 84 Greeks lived in the kaza of Boyabat and 1,213 Greeks in that of Ayancık. On the other hand, according to French Vital Cuinet’s book La Turquie d’Asie, 7,347Greeks, 314 Armenians and 46,291 Muslims resided in the kaza of Sinop in 1894. In 1903, there was a total of 6,894 Greeks in the Sinop sancak. Considering that this sancak’s total population was 144,064, Greeks made up 4,78% of the 1903 total population.[4]

In 1914, the total population of the sancak of Sinop was 160,401, of which 23,000 were Greek Orthodox Christians, according to D. Ikonomidis.[5] Living predominantly in the southeastern part of the sancak of Sinop, the Greeks were engaged in craftsmanship, shipping, fishing, tobacco farming and jewellery making.

According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 5,266 Armenians in six localities of the sancak of Sinope on the eve of the First World war; they maintained five churches and four monasteries.[6] Raymond Kévorkian mentions three “Armenian colonies” in the sancak in 1914: in Kuyluci, Ayancık and Göldağ “with a total population of 1,125, Gerze, on the Black Sea coast, had an Armenian population of 491. The densest Armenian population in the sancak, however, was to be found in the interior, in Boyabad and the surrounding villages: the total Armenian population was 3,650.”[7]

Greek Settlements[8]

Τμήμα Σινώπης – Section Sinope

Σινώπη – Sinope

Αγάτσολι – Agatsoli

Αγία Κυριακή – Ayia Kiriaki

Άγιος Δημήτριος – Agios Dimitrios

Γαρατζάκιοϊ – Garatsakioy (Trk.: Karatsaköy)

Καράσου – Karasu

Μουσουνού – Mousounou

Προφήτης Ηλίας – Profitis Ilias

Τσιφλίκ Προφήτη Ηλία – Tsiflik (Trk.: Çiflik) Profiti Ilia

Τσακίρογλου – Tsakiroglou

Τμήμα Αγιαντζίκ – Section Ayancık

Αγιαντζίκ – Ayiantzik (Trk.: Ayancık)

Γιοκαρίκιοϊ – Yiokarikioy

Στεφάνι – Stefani

Σίρνα – Sirna

Τμήμα Κέρτζε – Section Kertze (Gerze)

Κέρτζε – Kertze (Trk.: Gerze)

Κλησέκαριεσι (ή Τομούζαλαν) – Klisekariesi (or Tomouzalan)

Τζεβιζλίντερε – Tzevizlindere

Τμήμα Μποϊβάτ – Section Boyvat (Boyabad)

Μποϊβάτ – Boyvat (Boyabad)

Τμήμα Τσατάλζεϊντίν (Αγιαντών) – Section Tsatalzeintin

Αγιαντών – Ayianton

Γιάρνα – Yiarna

Μόρζα – Morza

Σεμιέ (ή Τόσος) – Semieh (or Tosos)

Τάιστα – Taista

Χέλαλτου – Helaltou

History

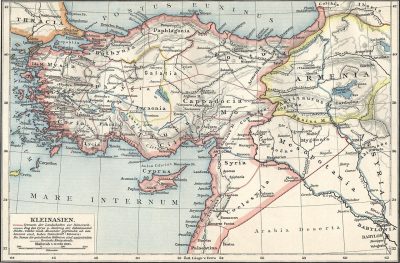

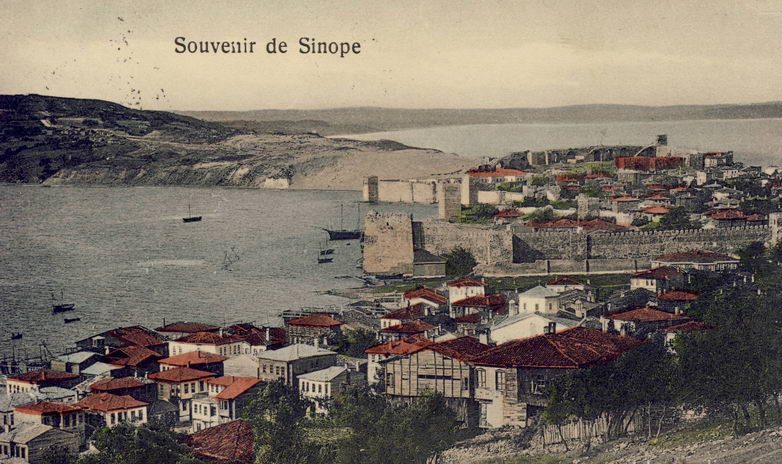

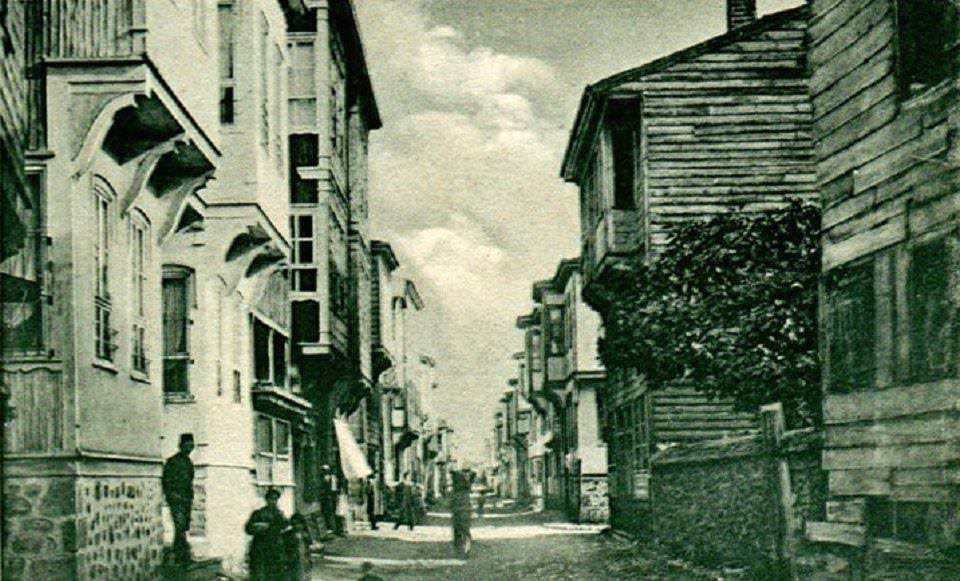

Sinope has played an important role as a cultural and trade center on the Black Sea for several millennia. The oldest traces of human settlement date back to the Bronze Age. Sinope was an early Black Sea colony of the Greek city of Miletus, located on the west coast of Asia Minor. The oldest archaeological evidence of Greek settlement dates from the late 7th century B.C., which fits the foundation year of 631 B.C. as reported by Eusebius of Cesarea. The historicity of an even significantly earlier first foundation before the mid-8th century B.C., mentioned by some ancient authors (Pseudo-Skymnos, indirectly Strabon), is disputed in modern research.

According to these accounts, the Thessalians Autolykos, Deileon, and Phlogios would have settled there after taking part in a campaign against the Amazons. A little later, before the arrival of the Cimmerians, there had been a new foundation by the Milesian Abrondas. A very early first foundation could be deduced from a passage in Strabon, in which it is said that in Sinope Autolykos was worshipped as the founder of the city and only later a new foundation by Miletus took place. If the early first foundation date is correct, Sinope would be the oldest Greek colony in the Black Sea area. In the 7th century B.C., Cimmerians who had invaded Asia Minor around 700 B.C. settled, among other places, “in the area around Sinope.” In the process, they are said to have driven out the early Greek colonists. A Cimmerian tomb attesting to the presence of the Cimmerians in this area was discovered a few years ago south of Sinope. After the expulsion of the Cimmerians by the Lydians in the last third of the 7th century, settlement by Milesians would have followed.

Sinope became one of the most important colonies, and many other colonies along the Black Sea coast – namely Amisos (today’s Samsun), Kerasous (Giresun) and Trapezous (Trabzon; Trebizond) – were founded from Sinope, which itself became very important. Sinope frequently minted on its coins the nymph Sinope on the obverse and a sea eagle above a dolphin on the reverse.

In 183 B.C., Pharnakes I conquered Sinope and made it the capital of the Kingdom of Pontos. After the defeat of the Pontic king Mithridates VI in 64 B.C. by the Roman general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, the Romans incorporated Pontos into their empire, and Sinope’s influence declined. Gaius Iulius Caesar founded a colony in Sinope in 46 B.C.

After the Seljuks captured the city in 1214, the city regained its importance and became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1458. After the devastating naval battle of Lepanto in 1571, the Ottoman Sultan Selim II had several hundred ships built in Sinope for the Empire’s fleet. For this purpose, workers from all over the Ottoman Empire were brought to Sinope, many of whom settled in the region. They contributed to the cultural diversity, as did Greeks (Pontos Greeks), Circassians, Georgians, Bulgarians and Turks.

On November 30, 1853, shortly after the outbreak of the Crimean War, the Russian Black Sea Fleet under Vice-Admiral Pavel Nakhimov attacked the Ottoman port of Sinope with explosive shells and set fire to all the ships lying there. In the process, large parts of the city burned to the ground. The event has become known as the Naval Battle of Sinope.

Destruction

The Russian vice-consul to Sinope described the situation of Christians one month after the Ottoman general mobilization of 2 August 1914 as follows: “Christians up to the age of 45 have been called to arms. Of the Christians from the cities, 400 registered in the labor battalions were sent to Taşköprü; Muslims of the same category remained in the city. As is known to all, at the initiative of the CUP [Committee for Union and Progress, alias Young Turks], the unfortunate Christian population of the Ottoman Empire is being oppressed in every possible way. Several Christian families of the city have remained without the protection of their men and are in a pathetic situation. The day before yesterday, women and children gathered in front of the konak [seat of city administration; governmental seat] weeping for their impasse they find themselves in and asking for help.”[9]

Aware of the disastrous consequences on the Christians of his vicinity, the Russian vice-consul of Sinope kept the Imperial Embassy of Constantinople up to date with new reports: “The persecution of Christians is continuing in both this area and the Empire in general. A few days ago, a group of local Greek family men were sent to Taşköprü as laborers, for the construction of the Boyabat-Kastamonu road. The local Christian families of the city are in a sorry state.”[10]

During the First World War, deportations both of Armenians and Greek Orthodox Christians followed. The town of Boyabad and the surrounding villages, where the Armenian population was densest, “constituted [vali; governor] Atıf’s first targets. As soon as he was appointed in early October 1915, he had 800 men arrested and interned in the mosque. Officially, some of them were sent to Angora [Ankara] to face court-martial. They disappeared on the way there. The rest of the population was deported by way to Çanğırı [Çankırı] , where prisoners from Istanbul saw it passing by in mid-October [1915]. These people were probably massacred near Yozgat, as were many other deportees from these areas near the Black Sea.

We have no reports about the fate of the Armenian men of Sinop and Bartın. We do know, however, that the rest of the population of these two localities was deportation by way of Sivas and, consequently must have endured the hell of Fırıncilar.”[11]

On 16 July 1916, Kuckhoff, the German vice-consul in Samsun, informed the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Berlin that he had “valid information that the entire Greek population of Sinope and the coast of Kastamoni [Kastamonu] province have been sent into exile. According to the Turks, exile equals extermination, because even those who escape being murdered will die, mostly of disease and starvation.”[12]

The 1919 documentation The Black Book of the Ecumenical Patriarchate at Constantinople mentions for this period: “The projected annihilation of the Greek element was put off, but in 1916, the Turks had recourse to other methods. Towards the end of July, 1916, an order was issued that the Greeks should deport. As a consequence, Sinope, Kerze [Trk: Gerze] with its neighbouring villages, up to Aladjam [Alacam], Ayadjik [Ayacık] with its villages, and Ayadin were evacuated. When the notables and merchants of Sinope asked why they were expelled, no reply was given to them. After eight days’ march, the inhabitants of Sinope and the remaining region reached Castambol [Kastamonu], where they received the order to immediately proceed to Tache-Keupru [Taşköprü], Poivat [Boyabad] and Saframbol. Their petition to the Vali Atif Bey to be allowed to remain at Castambol was rejected. A fire broke out at Sinope, destroying 400 Greek houses and shops. What little furniture was saved was stolen by the Turkish officials.”(13)

On 16 March 1917, the Greek-Orthodox Metropolitan of Amasia wrote about the situation of the deportees:

“After the houses were burnt down, and the plundering of their wealth and furniture had been affected, they went away [12]penniless and deprived of everything. The Turkish villages, in which they are penned up like cattle, are poor, and the inhabitants will not consent to give anything to the ghiavous (infidels). On the other hand, the Government have not taken any care of them, so that the programme of extermination succeeds marvellously. Now, on the basis of good and positive information, I inform you that two-thirds of the Christians expelled have perished in the Turkish villages of Angora. The remaining third are rapidly following the rest. The same fate applies to the Christians in the vilayet of Sivas, who had been expelled from the regions of Tripoli, Kerassounde [Giresun], Sinope, and Ineboli [Inebolu], to the vilayet of Castambol [Kastamonu]. It is impossible for me to describe the tortures to which these unfortunate people have been exposed, only because they are Christians and Greeks, during the days of expulsion. I should possibly be accused of exaggerating were I to relate only part of the atrocities committed, such as the abduction of young girls and the massacre of women and children, especially around Erekli [Ereğli], Kourou-kedje, etc.”[14]

In most cases, the deportees and expulsed Christians could not return to their destroyed homes. In his report on the situation in Pontos, the Greek Major G. Leontopoulos, who had also escorted the Greek Red Cross, mentioned in May 1919: “In Sinope, residents found their houses burnt down following their return from exil and are now living in fear. The fact that no-one has been murdered can be attributed to the fact that the majority are in a state of abject penury……”[15]

The mass Islamization of entire villages is confirmed by a report by Samsun’s Greek Orthodox metropolitan, Germanos Karavangelis, to the Patriarchate. In his report, a complaint is lodged about two villages in the Sinope area, Yukariköy and Serna, which were forced to convert to Islam in order to escape annihilation. A document of 25 January 1925 from the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs to the Mixed Committee for population exchange confirms these events. According to this document, the Turkish authorities refused the villagers of Serna the right to seek refuge in Greece, because they had converted to Islam and were registered as Muslims: “In response to your document Nr. 2153, I have the honour of informing you that the Sinope authorities, to which the village of Serna is subject (Ayiandon province), have declined permission for the departure of the villagers of Greek descent, in view of the fact that they converted to Islam several years ago.”[16]

After the First World war, Mustafa Kemal’s supporters have been perpetrating multiple acts of arbitrariness in the areas of Sinope and Inebolu.[17] On 15 May 1921, the armed bands of Arnavut Hüsein Bey and Tiriloğlu Mehmet Bey gathered 365 men, women and children from the Greek villages of Ekiztepe, Eltavut, Muamli and Karaşeyh, led them to the house of notable Savvas Tsigaloglou in the village of Muamli, and burnt them alive. Those who tried to escape were shot by the [irregulars], who had surrounded the house. “Following this atrocious and murderous act, all the houses were looted and set ablaze to wipe out all trace of the villages in the event of a future inquiry by international organisations.”[18]

On 12 July 1924, the Athens newspaper Pamprosfygiki reported the arrival of the last shipment of Greeks from Sinope, which numbered 1,411 persons. “Officially, no Greeks remained in the city. Unofficially though, there were still thousands wandering in the mountains or confined in harems and Turkish orphanages.“[19]