The Mush Plain is bordered to the south by the Taurus range. In the high valleys of the Taurus, south of this range lies the area of Sasun, which was the scene of the first massive massacres of Armenians under Sultan Abdül Hamid II in the 1890s.

Toponym

Both the Arabic form of the name Badlîs (Bidlîs) and the original Armenian form Baghaghesh (later shortened to Baghesh) probably go back to Aramaic ‘Balalêsh’. Bitlis is the Ottoman Turkish version of the toponym.[1]

Administration

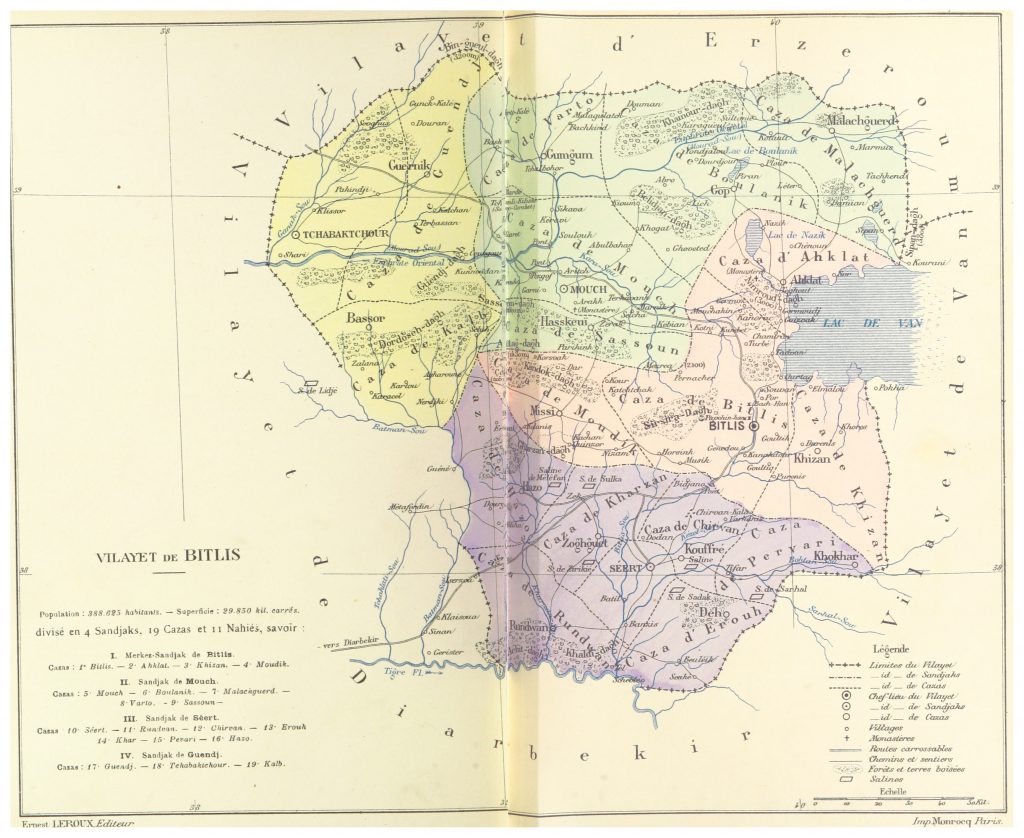

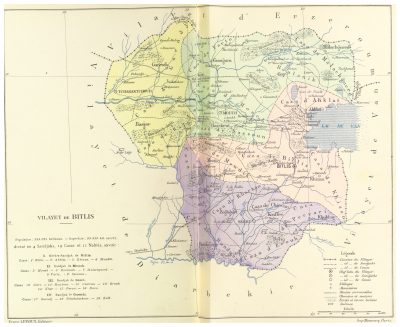

The Ottoman Province of Bitlis covered the larger part of the ancient provinces of Taron-Turuberan and Aghzniq (Aghznik) of Greater Armenia (Armenia Maior). The Vilayet Bitlis was formed as an administrative unit after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. Previously, it was part of the Muş sancak within the eyalet of Erzurum. In 1883/4, the sancak of Siirt was detached from the province of Diyarbekir, joining the Bitlis province. In the 1890s, the Bitlis province covered a territory of 29,800 square kilometers, consisting of the four sancaks of Bitlis, Muş, Siirt, and Genç, sub-divided into 19 kazas.

Population

As late as 1878 to 1879, the Vilâyet Bitlis had an overall population of 400,000 inhabitants, of which 200,000 were Armenians.

Vital Casimir Cuinet estimated the population of the province in the late 19th century as 398,625: of these 125,600 were Armenian Apostolic Christians, 3,840 Armenian Catholics (Uniates), and 1,950 Armenian Protestants. Furthermore, and according to V. Cuinet, there were 210 Greek Orthodox Christians (most of them residing in the Ahlat kaza), 372 Copts, 254,000 Muslims and 3,869 Yazidis in the province. The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, however, gave the total figure of the Armenian population in 1914 as 218,404, residing in 681 localities and maintaining 510 churches, 161 monasteries and 207 schools for 9,309 students.[2] Furthermore, and again according to the Armenian Patriarchate, there lived 15,000 Syriacs (Nestorians, Chaldeans, Syriac Orthodox), predominantly in the sancaks of Bitlis and Siirt, 40,000 Turks, 77,000 Kurds, 10,000 Circassians, 8,000 Kizilbash, 5,000 Yazidis and 47,000 Zazas, Timbali and Çarikli.[3] Armenians are spread over all areas of the Vilayet Bitlis, but were particularly numerous around Bitlis and in the Euphrates plain of Mush, with 200 to 300 villages.[4]

The main occupations of the population of Bitlis province were agriculture, gardening in the mountains, and cattle breeding. At the end of the 19th century, trade and crafts developed.

During the massacres of 1895-96, all the Armenian-populated villages of the province were looted. Many Armenians were forcibly converted to Islam. Despite the losses suffered, Armenians up to 1914 continued to form the majority of the population.

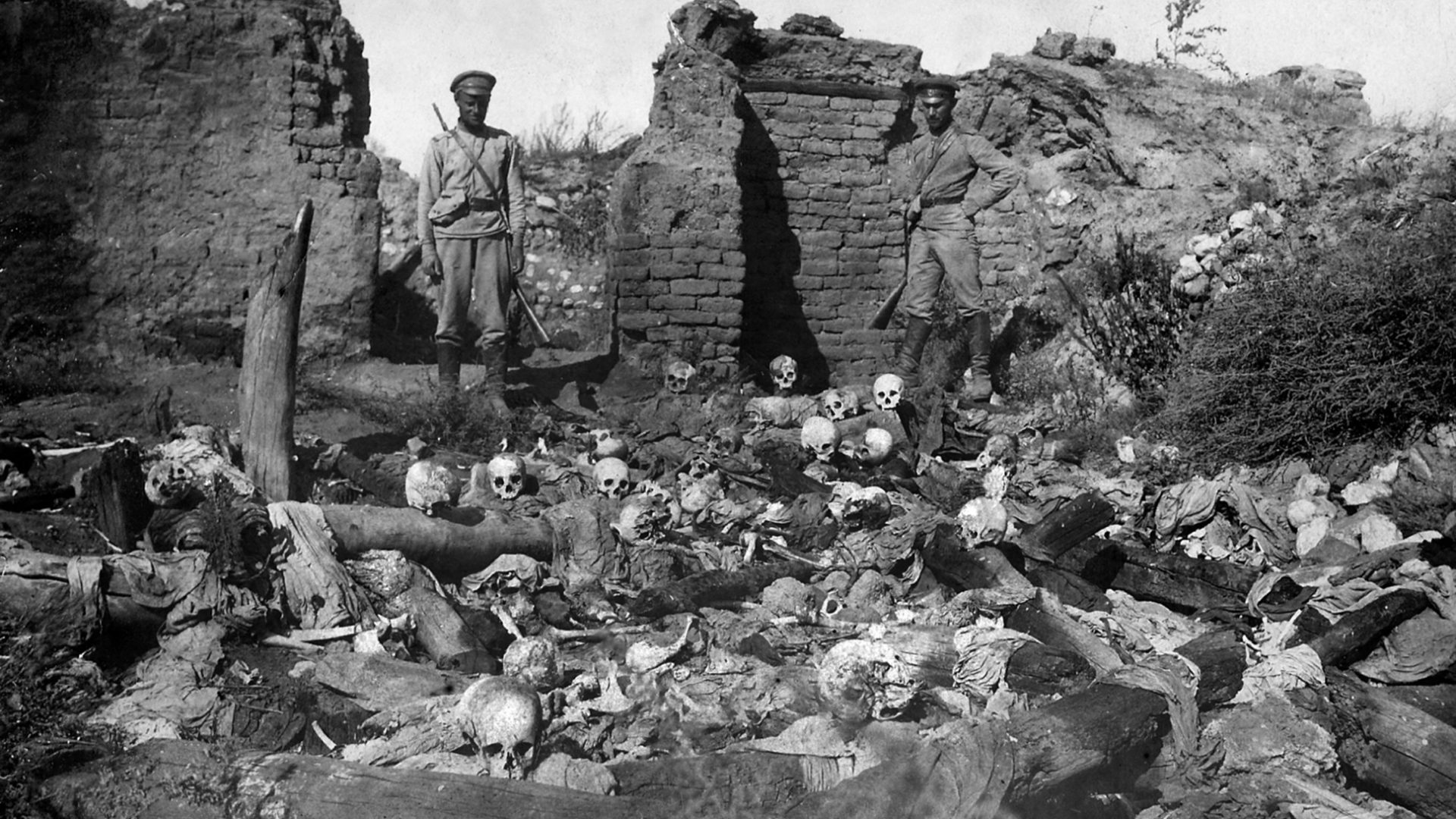

Of the approximately 200,000 Armenians of the province only 56,000 survived the massacres and deportations of 1915. Again, a part of these survivors was forcibly converted to Islam, or emigrated mainly to Eastern Armenia.

Christian Representation in Public Affairs

“The main fields of public life of Bitlis into which the Armenians entered were government politics, justice, finance and the secretariat. At the seats of the ‘sancaks’, Armenians were to be found in nearly every department (…) Two Armenians were usually elected to the administrative councils at the centres of the ‘sancaks’. Beside these the spiritual heads of the Apostolic communities were ex officio members, as were also the assistant governors who after 1896 were normally Armenian. In the councils of ‘kazas’ we find one, or more often, two Armenians who were at all times elected members. Two or three Armenians were also elected to the municipal councils at the central headquarters of the ‘sancaks’ of Bitlis, Muş and Siirt. (…)

In the judicature there were about as many Armenian judges as Turkish. The courts in the ‘kazas’ had one Armenian member. At the centres of the ‘sancaks’ there were usually two Armenians in the courts of first instance, and of appeal, one for the civil division, and the other for the criminal division, and either two or three in the commercial courts. (…)

The main function of the Armenians in the public administration of the province was the secretariat. They were clerks to the administrative councils, to banks, to land registries, to registrars of birth, to investigation committees for title-deeds, and to military transport committees. (…)

As there were only 210 Greeks living in the entire province, these being concentrated in the ‘kaza’ of Ahlat in the ‘sancak’ of Bitlis, very few of them were occupied in public affairs. Some however worked on the police, in political administration, in public health and in the post office. It is significant that they were appointed as superintendents of police, while the far more numerous Armenians were never selected. The Ottomans pursued this policy of appearing to patronize Christians while at the same time ensuring that the large Armenian community could not use this organization to exert their own independence.

The Syrian population, which was larger than the Greek, was concentrated in Bitlis and Siirt. So in these ‘sancaks’ especially several Syrian officials worked in public life, notably in the administrative councils.”

Excerpted from: Krikorian, Mesrop K.: Armenians in the Service of the Ottoman Empire: 1860-1908. London: Routledge, 2018, p. 29f.

Trades and Professions of Armenians

“Bitlis was a centre of commerce being on the intersection of the Tiflis-Trebizond route, and connected southward with route to Syria and Mosul. The Armenians in some parts of the province were occupied in agriculture and cattle, breeding, but their main employment was in trade and crafts. In the manufacture of carpets, cloth and domestic utensils the Armenian competed with Kurds and Turks, but the rest of commerce and handicrafts was largely in their hands. They were engaged in many trades; in the goldsmith’s art, sewing, painting, building, blacksmith’s craft, farriery, pottery, woodwork, shoe making and general trade. A. Dô [A-To, i.e. Hovhannes Ter Martirosian], an Armenian writer who visited Bitlis in 1909, recorded the occupation of Armenians thus:

‘The Armenians of Bitlis are skilled and have natural ability. They show a special flare for trade. In this district the commerce is for the major part in their hands, although disturbances and massacres have repeatedly come to disrupt the activities and production of this resilient people.`”[5]

History

In 640/1 the Arabs subdued the districts of Bitlis, Muş, and Siirt, but in 885 the Armenians threw off the yoke of Arab domination under the leadership of the princes of the Bagratid (Bagratuni) dynasty and established a kingdom, which lasted until 1054.

The Kurdish Principality of Bitlis (Kurdish: Badlis) existed from 1182 to 1847 and emerged from the tribal federation of the Rojaki (Rozagi). The Rojaki defeated the Georgian king David III and conquered Bitlis and Sason in the 10th century. The principality occasionally came under the rule of the Turkmen Ak Koyunlu (1467-1495) and the Iranian Safavids (1507-1514). After the demise of the Ak Koyunlu, the Rojaki princes regained their independence. In 1531, Prince Sharaf Khān entered into an alliance with the Safavids and was assassinated by Olama Takkalu in 1532.

In the 11th century the Seljuks, and in the 14th the Mongols conquered Bitlis and its surroundings. Shortly afterwards came the Ottoman Turks, and as the Kurdish tribes, probably immigrating from Iran, had become a large element in Bitlis, Muş and Van, it was the Kurdish chief who ruled under the suzerainty of the Ottoman sultans. In 1846 the Ottomans broke the power of the Kurds and brought these territories under the direct subordination of their regular government.[6]

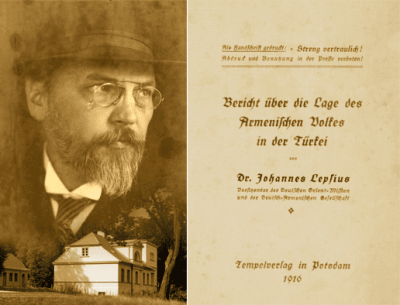

The reform attempts that the six European ‘Powers’ of the time, especially Russia, Germany and Great Britain, tried to impose on the Ottoman government in 1913 remained ineffective in the ‘Six Provinces’, and in particular in the provinces of Van and Bitlis. This is also evidenced by correspondence that the German theologian and chairman of the German Orient Mission, Dr. Johannes Lepsius, sent to the German Foreign Office on 18 April 1913; among other things, one document stated:

“But none of these promises could come true, despite our incessant efforts, and soon the situation became such that from Van, Ahtamar, Bitlis, Mouche [Mush] , Sghert [Siirt] began to arrive dispatches announcing new crimes and more than 30 Armenian victims. (…)

Unfortunately, we are forced to admit with pain that Van, Bitlis, Sghert, have sent us dispatches announcing that no measures had been applied, that the state of things continued to be the same and that the population was living in a state of terror.

Such was the situation when an official communiqué appeared, an attempt to refute the incriminated facts, based on the reports of the Governors-General of Van and Bitlis.”[7]

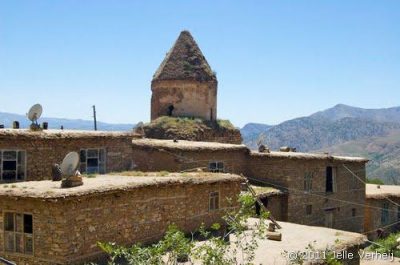

Richard Hovannisian: The City of Baghesh / Bitlis

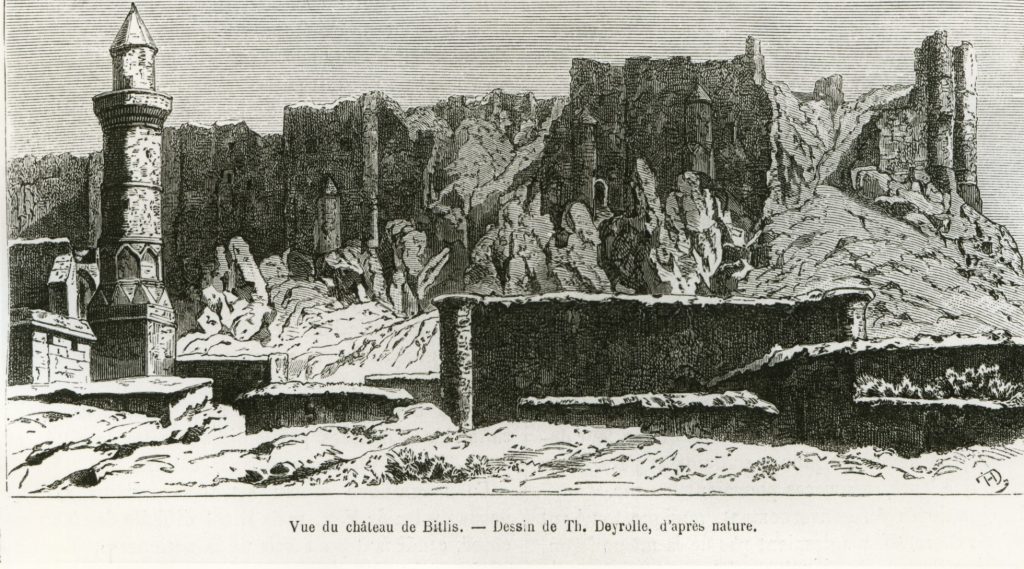

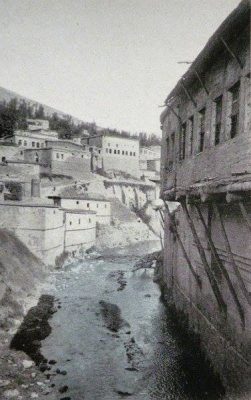

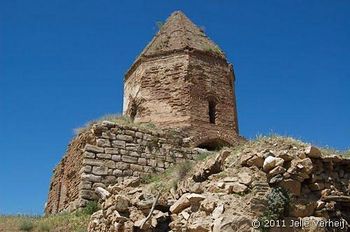

“Baghesh or Bitlis is located on the most important pass in the eastern (Armenian) Taurus Mountains, the city itself fanning upward like an amphitheater from the river vale. The abundance of water and natural springs keep Bitlis an evergreen city some 5,000 feet above sea level. The rich damp soil supports verdant, aromatic orchards of pears, apples, plums, apricots, grapes, quince, pomegranates, cherries, figs, mulberries, walnuts and filbert nuts. Historically an emporium of trade, the city of Bitlis at the core of the vale is where Armenian artisans engaged in the arts and crafts, especially in leather, lace and fabrics, painting, jewelry, and weaponry. Unlike dwellings in many other parts of historic Armenia, the homes here are made of stone, and many are multi-storied. Towering above the city is the medieval fortress, which for centuries was virtually impregnable, being protected by a series of trenches and drawbridges and a dominating position over the narrow, difficult pathway leading upward. Amrdolu Surb Hovhannes Mkrtich (Saint John the Baptist) or Surb Karapet (Holy Precursor) was the home of the most active scriptorium for the copying of manuscripts.

(..) The regions of Baghesh and Taron came under successive Arab ruling clans and were among the first areas of Greater Armenia to sustain permanent foreign immigrant populations—Arab and then Kurdish tribes. For several centuries, Baghesh/Bitlis was the center of a powerful Kurdish principality, in which the Armenian subjects had special taxes and duties imposed upon them yet maintained their vital roles in commerce and agriculture. Even in the harshness of daily existence, the Armenians continued to build churches and monasteries, apparently with the consent or at least tolerance of their Kurdish overlords.

The Baghesh/Bitlis region was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Selim the Grim (1512-20), who extended many privileges to the Kurdish notables in recognition of their assistance against Safavid Iran. The Kurdish emir or khan of Bitlis gradually extended his authority over the mountains of Sasun, the plain of Mush, and the eastern and northern shores of Lake Van. As the Ottoman sultanate declined, Kurdish power waxed strong and for a time extended all the way to Van and Diarbekir, the emirate virtually becoming a state within a state.

This relationship was finally broken in the mid-nineteenth century, when the Ottoman army occupied Bitlis and exiled the khan. Bitlis was then placed within the large province of Van and shortly thereafter in Erzerum until the breakup of these super provinces into smaller yet still sizeable vilayets. (…)”

Excerpted from: Hovannisian, Richard G.: Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush. In: Hovannisian, Richard G. (Ed.): Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush. Costa Meza, California: Mazda Publishers, 2001, p. 2f.

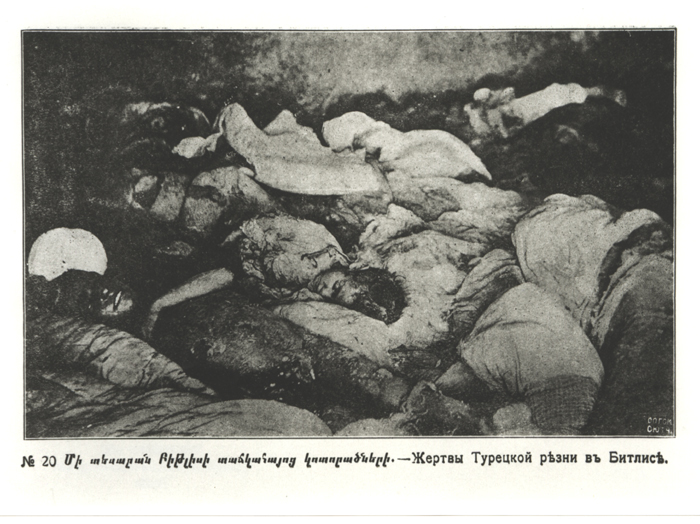

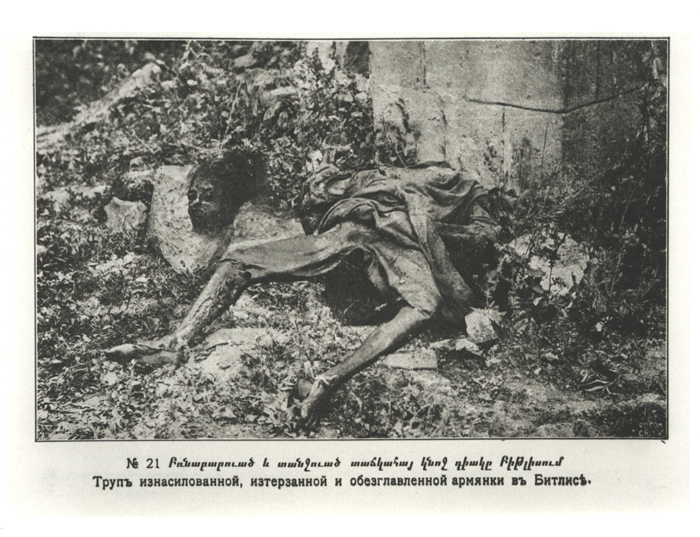

Deportations and massacres in the Vilayet of Bitlis:

In the Vilayet Bitlis, the deportations (…) did not last long, but the inhabitants of the towns and villages were massacred on the spot in order to leave their homes to the waiting muhacirler [Muslim refugees]. Men and women were tied together by the dozen and thrown into Lake Van. Cevded Bey, on his way marked with blood and horrors of all kinds, came from Van via Sairt [Siirt, Srerd] to Bitlis in June. There he first collected a tribute of 5000 Turkish pounds from the Armenians. He then hanged Hokhingian and twenty other leaders, most of whom had been nursing the wounded in the military hospitals. On June 25, the whole town was surrounded; then all men fit for military service were taken from their homes and shot outside the village. The young women and children were distributed, and the ‘worthless rest’ were driven away southward and, as it was said afterwards, drowned in the Tigris.”

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 2. Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918

“A Pre-Established Plan”

“The massacres of the Armenian population of the vilayet of Bitlis are generally presented as the direct effect of the ‘events’ in the neighboring region of Van, as an act of revenge for the military defeat suffered by the Turkish forces in Persian Azerbaijan and during the subsequent retreat of Halil’s Expeditionary Corps. However, the fragmentary information available to us indicated that, from 25 to 27 April 1915, a long meeting took place halfway between Siirt and Bitlis between Dr. Nazim and the vali of Bitlis, Mustafa Abdülhalik [8]. This provides grounds for supposing that the order to extirpate the Armenian population of the region, as well as the methods to be used in doing so, were discussed much earlier.

In Bitlis, late in April, Vali Andülhalik had three local Armenian leaders arrested and hanged. This was no longer the harassment or violence that typically accompanied the military requisitions or general mobilization, but a move designed to condition the population psychologically. The Dashnaks were the direct target, although curiously they were still being treated respectfully in Mush. The authorities probably posed the problem in terms of power relations. After deciding to eradicate the Armenians, they had to find the necessary means to carry out the operation. There was a tremendous difference between what was required in Bitlis and on the plain of Mush. In Bitlis, there was practically no danger that the Armenians would react if they were attacked, because there the ARF [Armenian Revolutionary Federation; Dashnaktsutiun] did not have a network worthy of the name. The plain of Mush, in contrast, was almost entirely Armenian and a Dashnak stronghold. Abdülhalik could do practically whatever he wanted with the forces at his command in Bitlis; he knew that he would have to mobilize a much stronger force to liquidate the Armenians in the plain of Mush. In other words, the retreat of the Fifth Expeditionary Corps under Halil (Kut) and the 8,000 men in Cevdet’s ‘butchers’ battalions’ (kasab taburis) (…) may be regarded as the result of a decision taken in consultation with Istanbul; it made it possible seriously to envisage translating plans into action in the vilayet of Bitlis. (…)

Rather than an act of vengeance, then, what was involved was the implementation of a pre-established plan. It was made possible by the arrival of Halil’s and Cevdet’s forces, whose connections with the Special Organization [Trk.: Teşkilat-i Mahsusa] was no secret.”

Excerpted from: Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011, pp. 337f.

Johannes Lepsius: Requisitions, Desertion and Forced Recruitments in the Vilayet Bitlis

“(…) The events in Vilayet Bitlis are related to the events in Vilayet Van. The final catastrophe took place only after the Russians had cleared Van. (…)

Since the outbreak of the war, the towns and Armenian villages were filled with Turkish and Kurdish gangs, who were recruited as militias into the army. The gendarmes were engaged in robbery and looting under the pretext of requisitions. The Armenians were deprived of all the food they had saved for the winter, and they feared a famine in the spring. In addition to the Armenians who had been drafted into the army, Armenians of all ages were requisitioned in any number to build roads and carry loads. The porters had to carry heavy loads of up to 70 pounds [35 kilograms] through the snow-covered mountains to the Caucasus front throughout the winter. Poorly fed and without protection against Kurdish raids, half of them perished on the way, often only a quarter returned. After the battles of Sarıkamiş and Ardahan, when the Caucasian army was quartered in snow and ice, many soldiers deserted. But for every five Turkish deserters there was at most one Armenian.

Individual deserters returned to their villages. The gendarmes went from village to village with lists of deserters to demand their extradition. At the same time, they searched houses for weapons. If the deserters were not found, their houses were burned down and their fields confiscated. These raids, which the gendarmes organized, occasionally led to clashes. Thus, in early March [1915], Commissar Nazim Bey and Mülasim Cevded Bey came to the Armenian village of Tsronk with 40 Zaptiehs. During an exchange of bullets with a fugitive, a gendarme’s horse is shot from under his body. He returns to the village, takes a good horse from the peasants, gets paid 40 Turkish pounds as a substitute for the dead horse, sets fire to 25 houses, kills the men of the village and confiscates the fields. In Armedan, Turkish volunteers are quartered in Armenian houses. In return for the food, the leader rapes the daughter-in-law of his landlord. Similar things were repeated in other villages.

The Kurds in the mountains had no desire to go to war. They preferred to plunder Armenian villages. This was less arduous and more profitable. (…) The Kurdish tribe Abdul Mecid of Melasgert [Manazkert, Mantsikert] occupied the mountains of Chur, plundered the Armenian villages and massacred the inhabitants. (…)

Despite all the harassment, the Armenians remained calm, endured the assaults and were not tempted to resist. (…)

At the end of April, probably due to the events in Van, the Vali changed his apparently benevolent attitude towards the Armenians. On May 1, three Armenians were hanged in Mush and the Armenian quarter was surrounded by military without instigation. The Vali publicly threatened a massacre. At the same time, all Armenian men who were still somehow fit were conscripted to the road-building and load-bearing columns (Hamalar-Taburi) and without regard to whether the families remained without breadwinners. For example, the headman of the village of Goms in the Mush Plain was ordered to provide 50 oxen and 50 men for transportation purposes. Despite the fact that the village had only 70 men, the old men included, he brought together 50 oxen and 45 men and offered the military exemption tax for the five missing men. The Müdir of Akcemak, who had come to Goms, wanted to be satisfied with this, but his companion, the Kurd Mehmed Amin, an enemy of the village chief, took the absence of the five men as an opportunity to whip the village chief and shoot seven Armenians. A clash ensued in which seven gendarmes and another 20 Armenians were killed. (…)”

Excerpted from: Lepsius, Johannes: Der Todesgang des Armenischen Volkes: Bericht über das Schicksal des Armenischen Volkes in der Türkei während des Weltkrieges. Reprint der Ausgabe Potsdam 1930, Heidelberg 1980, p. 112-115