Toponym

Çeşme (or Cheshme) is originally a Persian placename since the first settlement 2 km south of the present-day center (Çeşmeköy) was founded by the Seljuk military commander Tzachas and pursued for some time by his brother Yalvaç before an interlude until the 14th century. The name Çeşme means ‘spring, fountain’ in Persian (چشمه) and possibly draws reference from the many Ottoman fountains scattered across the city.

Population

The Diocese of Çeşme comprised thirty-one communities with a total of 60,496 Greek Orthodox inhabitants.[1] Until 16 September 1922 Greeks consisted the majority of Çeşme and its environs.[2]

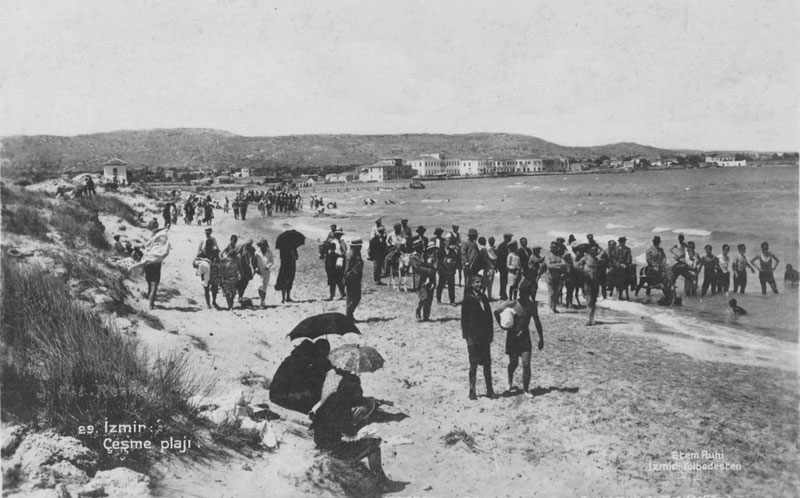

Çeşme regained some of its former lustre starting with the beginning of the 19th century, when its own products, notably grapes and mastic, found channels of export. The town population increased considerably until the early decades of the 20th century, with immigration from the islands of the Aegean and the novel dimension of a seasonal resort center becoming important factors in the increase. In 1924 with the forcible Population exchange Muslims from Greece mainly from Karaferye settled to the town.

History

The urban center and the port of the region in antiquity was at Erythrai (present-day Ildırı), in another bay to the north-east of Çeşme.

Most probably, the ancient Greek polis of Boutheia (Βούθεια or Βουθία in ancient Greek) was situated in Çeşme. In the 5th century B.C., Boutheia was a dependency of Erythrae and paid tribute to Athens as a member of the Delian League.

The town of Çeşme itself experienced its golden age in the Middle Ages, when a modus vivendi established in the 14th century between the Republic of Genoa, which held Chios (Scio), and the Beylik of Aydinids, which controlled the Anatolian mainland, was pursued under the Ottomans, and export and import products between western Europe and Asia were funneled via Çeşme and the ports of the island, only hours away and tributary to Ottomans but still autonomous after 1470. Chios became part of the Ottoman Empire in an easy campaign led by Piyale Pasha in 1566. In fact, the Pasha simply laid anchor in Çeşme and summoned the notables of the island to notify them of the change of authority. After the Ottoman capture and through preference shown by the foreign merchants, the trade hub gradually shifted to Smyrna, which until then was touched only tangentially by the caravan routes from the east, and the prominence of the present-day metropolis became more pronounced after the 17th century. In 1770, the Çeşme bay became the location of naval Battle of Chesma between Russian and Ottoman fleets during Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774). After the Balkan Wars, Bosniaks mainly from Montenegro settled in the environs of Çeşme such as Alaçatı and Çiflikköy.

Jakob Philipp Hackert: The destruction of the Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Cheshme, 1771 (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Chesma#/media/File:Hackert,_Die_Zerst%C3%B6rung_der_t%C3%BCrkischen_Flotte_in_der_Schlacht_von_Tschesme,_1771.jpg)

Destruction

Before the First World War: Expropriation, Terror, Murder, Rape, and Expulsion

Since May 1914, the kaza Çeşme was affected by the expulsions and persecutions of the Greek Orthodox inhabitants orchestrated by the provincial authorities. For this purpose, the authorities used, among other things, the settlement of Muslim refugees from the Balkans (muhacir; pl. muhacirler), who soon took part in acts of violence against the long-established Christian population.

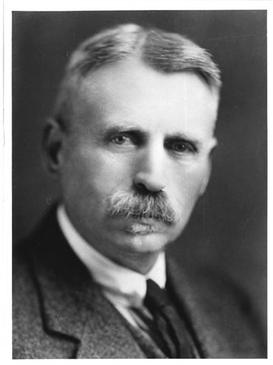

“The Greeks of Kato-Panaya [in the kaza of Çeşme] ran for Chios, gunfire at their heels. Villages in the Çeşme district, west of Smyrna, were almost entirely evacuated. [George] Horton, [U.S. consul general to Smyrna], reported some 23,000 Greeks ‘expelled.’ Many Greeks, he wrote, were now living ‘in the open air.’ (…) Horton recognized the authorities’ signature on the violence. ‘It is only when the Mussulmans are officially incited against the Christians that they resort to brutality,’ he wrote.”[3]

Therefore, during a parliamentary session, the deputy for Aydın, Emmanouil Emmanouilidis, asked the Ottoman Minister of the Interior, Mehmet Talat, why the refugees were being settled in Greek villages, of all places, when there was enough open land between Üsküdar to the Gulf of Bassora. Minister Talat gave the following answer:

„Indeed, there are enormous parcels of land there, but in order to settle them the way Emmanouilidis Efendi has said, we first need 15-20 million pounds, something which we do not have. If we had sent them and dispersed the muhacirs [who were a total of 270 thousand], they would all be dead of hunger, and Emmanouilidis Efendi would not be happy.”[4]

Less than a year after Talat explained why it was unacceptable to settle Muslim refugees in Mesopotamia, he had two million Ottoman Armenians deported to that region.

Documentation by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (1919):

“A ruthless persecution was started all over this Diocese (…) which began at an early date. Turkish immigrants from the territories occupied by Serbia established themselves in the various Greek communities, and took away the inhabitants’ houses and property by force; they also deprived them of their savings, the produce of many years’ hard labor, and terrorized the Greek population in general.

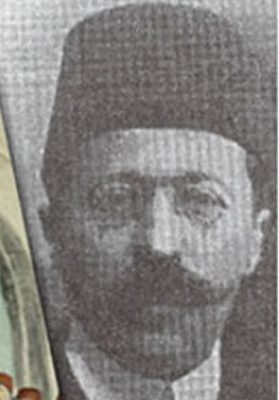

This hostile attitude of the immigrants and Turks was supported by the Government officials and is proved by a document bearing the signature of Karabina Zade All (a rich proprietor of the hotels and the hot baths of Chesme), in his official capacity as organizer of the bands of the peninsula of Erythrea, and addressed to the Chief of the Band, and the officers of the Gendarmerie. Moreover, the complicity of the Government officials in the destruction of this Diocese is revealed, beyond doubt, in a report of the Metropolitan of Chesme, under date of the 20th May, 1914, as follows : —

‘A few days ago the work of accommodating 1,300 Moslem immigrants in the Churches and 150 Christian houses had finished. The inhabitants now expected to be able to attend to their work of agriculture as before, earn a living and pay the Government taxes. But such was not the case, for the Government officials called the muhtars up and ordered them to prepare another hundred houses, as the above 150 were not sufficient to accommodate the Turkish immigrants. The muhtars and notables remarked that no empty houses were available, as already the largest of the houses had been requisitioned for that purpose. The authorities, however, persisted, and proceeded, assisted by armed gendarmes and tobacco-keepers, to enter the houses and shops occupied by the Christians, robbing them of every-thing they possessed, and ordering the tenants out under penalty of death, adding that there was no room any more for Christians by the side of the Moslems, and that therefore they should go to Salonica.

Accordingly, all the houses and shops of Chesme fell into the hands of the Turks, and the inhabitants were turned out into the streets in a shameful manner by the Government, with nothing else but the clothes they wore. Some few managed to take some coverings with them.

The inhabitants panic-stricken at the reports of massacre, were obliged to leave; some took refuge in the neighourhood with their families, others proceeded to the sea-shore village of Cato-Panayia to take the first ships available and expatriate.

Plundering by the authorities and immigrants lasted the whole night long. Those houses and shops that had been closed by their owners were broken into by means of hatchets, and everything they contained taken away. Money, jewelry, furniture, manufactured goods, all kinds of chattels and utensils fell into the hands of the robbers.

The whole property of a flourishing village, numbering 1000 Christian families, passed into their hands, and the loss is estimated at a considerable sum.

All this took place with the consent and assistance even of the authorities. During three whole days and nights, armed Turks from Chesme and Ovadjik [Ovacik] transported their booty from Cato-Panayia and this place to Ovadjik, at half an hour’s distance towards the interior. The Caimacham [kaymakam] pretended not to know either what had taken place, or declared himself incapable of maintaining order, even going so far as to own it to me when I remonstrated with him.

Moslem fanaticism, which the Turkish Press has recently done its best to excite, combined with the rapacious instinct of certain miscreants, are the main causes, I believe, that have encouraged the Turks of the neighborhood to oppress the Christians.

These malevolent instigations naturally gain ground as long as the authorities tolerate with impunity such acts, for the perpetrators knowing that no punishment awaits them, and profiting by the abnormal present conditions, will continue unconcerned their work of destruction. In conclusion, I have to remark that the Christian communities of Chesme and its surroundings are prepared to expatriate owing to the menacing attitude of the Moslem immigrants, and it is with great difficulty that I, together with some notables, have been able to prevent them so far from doing so. It may be considered certain, however, that a fresh immigration, even in small numbers, will take place, and a repetition of the outrages already perpetrated will have the effect of obliging the whole Diocese to expatriate although nothing short of ruin awaits them.’

What was foreseen by the foregoing communication, came to pass, and it is under the most tragic conditions that the following villages were evacuated, in a very short space of time :

- CATO-PANAYIA, 2. CHESME, 3. ALATSATA, 4. AYIA-PARASKEVI, 5. OVADJIK, 6. REIZ-DERE, 7 KEUMEYALESSI, 8. AGRIELIA, 9. SAIPI, 10. ERITHRE, 11. ZIGHOUI, 12. AHIRLI, 13. SAIPI, 14. ABAR-SEKI, 15-16 BIG AND SMALL MOLDOVANI 17. TEKKES, 18. MONASTIRI, 19. TEPEPOXI, 20. YENI- LIMAN, 21. HAS-SEKI, 22. SARPINDJIK, 23. SAZAKI, 24. VOINAKI, 25. SALMANI, 26. EGRI-LIMAN, 27. DENIZ- GUEREN, 28. KIOUTSOUK-BAKTCHE, 29. MELI and 30. AYIA-PARASKEVI.

In order to hasten the departure of the Christians and render it inevitable, the criminals started committing all kinds of acts of terrorism so as to scare the inhabitants. Two workmen, natives of Ahirli, were strangled in the mines of Monasteri. Soldiers and Turkish immigrants at Saipi wounded some of the Christian inhabitants and murdered Andrea Monastirli, Haralambos Roumeliotis, the wife of Petro Hadji Kyriakou, Yani Tchobani, Stamati and some others. Other fiends murdered Haralambos Panayirtou Ismirli, a citizen of Yeni-Liman; the keeper Arif beat two old women of Micro Moldovani, the paralytic wife of pope Stamati, and Chryssafi Diasouri, because they refused to be islamized. He then put them in a boat and paid out of his own pocket that they might be deported to the opposite island, Englezonissi, so that no Christian foot should any longer soil the peninsular of Erithrea.

Lately the village, on the island of Englezonissi, has been evacuated also. On the 27th June, 1914, regular troops landed at six different points of the island, occupied it, and blockaded the houses in search of arms. They killed fifteen Christians. The other inhabitants took refuge in Mr. Joreau’s house, a French citizen. The two daughters of Aspromati (fourteen and seventeen years old) were successively violated by twenty -five soldiers.

Following these incidents, the inhabitants of the Island, together with the Christians from the surrounding country who had taken refuge there, embarked for Greece, and especially to the isle of Chios where the inhabitants of this district also went.”[5]

The Greeks of the canton (kaza) of Çeşme were “deported in a body”, and “returned to their homes only after the liberation of the town by the Greek army.”[6] The returnees were expelled a second time after the retreat of the Greek forces in September 1922.