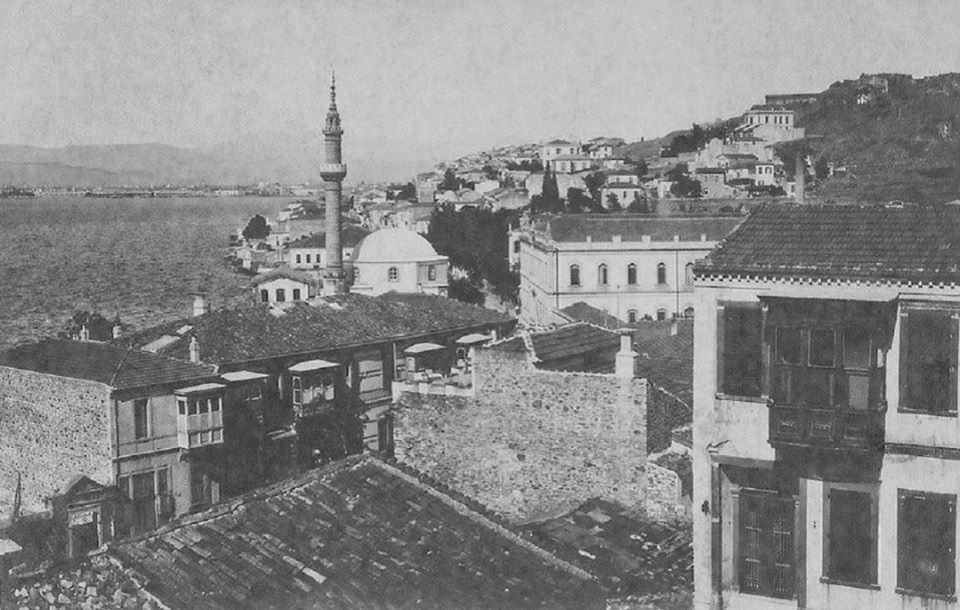

In April 1825, the Austrian general, diplomat and travel writer Anton Prokesch von Osten stayed in Urla. In his Mittheilungen aus Kleinasien (Notices from Asia Minor) he gave the following account:

“The bay of Vourla is not inferior to any other part of the beautiful gulf of Smyrna, especially in the present season, when the scent of sacrifice rises to the sky from all the mountains, and all the fields are adorned with wreaths. …In the hot season, the warships standing on the roadstead of Smyrna love to go to Vourla, as one goes from cities to country houses, to enjoy lighter, faster air, a purer sky and pleasant freshness…. The shore also offers many conveniences for bathing the crew, only they must not go too far from it, or if they swim by the ship, a circle should be drawn with boats beforehand, because there are a lot of shark fish in this bay. These abominable sea hyenas often follow the boats without shyness, like a dog running behind its master. … At this [bay] the land of Vourla, with a few coffee houses, a toll house and a mosque, is devastated by the pirates, who from time to time rob people and cattle even on this shore, and otherwise do mischief. … The nearest surroundings of Vourla are exceedingly prosperous. There is a great trade in dried figs and raisins; Chesme, Vourla and Smyrna supply the whole of Europe with these fruits.”[1]

Toponym

The city’s ancient predecessor settlement was called Klazomenai. The later Greek name of the city, which was also used in Turkish times, is Vourla (Βουρλά), meaning ‘marshlands’ and the town was cited as such in western sources until the 20th century. The Byzantinename Bryela means Woman of God, i. e. Holy Mary. It has been suggested that due to the transposition of vowels Bryela has become Vourla.

Population

The town’s population were mostly Greeks until the forcible population exchange of 1923.[2] The kaza of Vourla belonged to the Diocese of Ephesos, which comprised eighty-five communities with a total of 164,467 Greek Orthodox inhabitants.[3]

Notable Greeks born in the kaza of Vourla

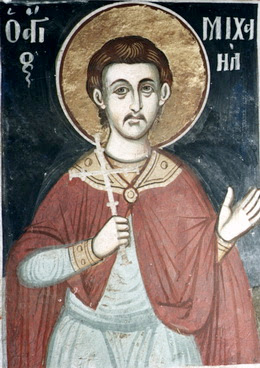

- Michael of Smyrna, or Michael of Bourla, or Michael Burlites (* ca 1754, Vourla; † 1772 in Smyrna), canonized neomartyr of the Greek Orthodox Church

- Georgios Afthonidis (Γεώργιος Αφθονίδης, 1789-1867, Athen) member of the Filiki Eteria and worker of the Ecumenical Patriarchate

- Giorgos Seferis (born Γεώργιος Σεφεριάδης – Georgios Seferiadis; 13 March [S. 29 February] 1900, Vourla – 20 September 1971, Athens), Greek writer and Nobel laureate in literature; diplomat.

Giorgos Seferis: Two Poems

OUR LAND IS CLOSED

Our land is closed, nothing but mountains

on which day and night the low ceiling of the

of the sky.

We have no rivers we have no wells we

have no springs,

only a few cisterns, empty too, in which it resounds and

and to which we pray.

A stale echo, hollow, it resembles our loneliness

resembles our love, resembles our bodies.

It seems strange to us that once we could build

our houses our huts and pens.

And our weddings, the fresh wreaths and bread curls

become unsolvable riddles to our soul.

How did our children come to be? how did they grow up?

Our land is closed. The two black symplegades(4)

close it. When we walk on Sunday

we go down to the harbors to catch our breath

we see in the evening glow

Pieces of wood in splinters from a voyage they did not complete

Corpses that no longer know how to love.

The Last Day

The day was cloudy. No one could come to a decision;

a light wind was blowing. ‘Not a north-easter, the sirocco,’ someone said.

A few slender cypresses nailed to the slope, and, beyond, the sea

grey with shining pools.

The soldiers presented arms as it began to drizzle.

‘Not a north-easter, the sirocco,’ was the only decision heard.

And yet we knew that by the following dawn

nothing would be left to us, neither the woman drinking sleep at our side

nor the memory that we were once men,

nothing at all by the following dawn.

‘This wind reminds me of spring,’ said my friend

as she walked beside me gazing into the distance, ‘the spring

that came suddenly in the winter by the closed-in sea.

So unexpected. So many years have gone. How are we going to die?’

A funeral march meandered through the thin rain.

How does a man die? Strange no one’s thought about it.

And for those who thought about it, it was like a recollection from old chronicles

from the time of the Crusades or the battle of Salamis.

Yet death is something that happens: how does a man die?

Yet each of us earns his death, his own death, which belongs to no one else

and this game is life.

The light was fading from the clouded day, no one decided anything.

The following dawn nothing would be left to us, everything surrendered, even our hands,

and our women slaves at the springheads and our children in the quarries.

My friend, walking beside me, was singing a disjointed song:

‘In spring, in summer, slaves . . .’

One recalled old teachers who’d left us orphans.

A couple passed, talking:

‘I’m sick of the dusk, let’s go home,

let’s go home and turn on the light.’

History

Urla was the site of the Ionian city of Klazomenai and an important cultural center also in its Hellenistic period. Pieces of art and sculpture found during excavations are now exhibited in the Louvre, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens or in İzmir Archaeology Museum.

The oldest attested olive oil production facilities were recently discovered in Klazomenai. The traces indicate first exports of olive oil by way of sea.

Olive oil extraction installation dating back to the third quarter of the 6th century B.C. uncovered in Klazomenai is the only surviving example of a level and weights press from an ancient Greek city and precedes by at least two centuries the next securely datable earliest presses found in Greece.

In the summit of Ottoman power, during the 16th century, Urla was almost entirely incorporated into the pious foundation established by Ayşe Hafsa Sultan for the revenues and the maintenance of the complex she had had built in Manisa in the 1520s. With the decline of the Ottoman power, the town, placed along with the entire peninsula at the frontier of the Aegean Sea difficult to control, frequently saw itself at the mercy of plunderers. Smyrna’s rise as an international trade port partially relieved Urla from its security concerns, while it also gradually increased its dependency to the neighboring metropolis. A quarantine center was established in Urla in 1865 through French initiative, in the island opposite Urla quay that bears today the very name of Karantina, and where part of the site of ancient Klazomenai also extends.

Destruction

Massacres and Deportations during WW1

The Greek Orthodox population of the kaza was deported during the First World War, with the exeption of the kaza’s administrative center, the town of Vourla, itself.

“KOLIDJA-ORTADJA [Kolica-Ortaca], 31. MENTESSI, 32. DOCTOR’S ISLAND (latro-Nissi). These villages were also evacuated under the same conditions. The whole of the region including the town of Vourla suffered immensely, not only from the malefactors who openly terrorized the population, but also from the Moslems of the country, whom the Government armed. The shepherd, Lambros Stoupi, was murdered near Bournoussous, and so were also Dem. Kalpaxiotis and Argiris Demitriou, near Vourla, Manolis Kaelos Sariyannis in the village of Soghout, Georgios Fotinakis at Kiman-reiz, and Panayiotis Marketas.

The inhabitants of Vourla, threatened by expulsion, were saved by Talaat, who ordered ‘Sindillk doursoun’ (they may remain for the present). Eleftherios Akritas of Gul-Baktche [Gül Bahçe], a peasant, Manolis, of Ipsili, and the shepherd Kyriakos Axiotou, a newly born babe, an old man, Tsemberlis, Costas Orphanos, and Basil Karadais of Kilizman, were also killed.”[5]

“Feb. 1915: E. Hadjiconstantinou and Manatas were imprisoned without any reason.

May 1915: Two shepherds, N. Chloros and I. Paraparis, were murdered. E. Vretos was severely wounded. S. Dimakis, M. Karakyriakos and M. Karankolis were murdered. Many were arrested, imprisoned and expelled to Van and Mosul, amongst them being the brothers Vati and G. Bogdanos.

June 1915. G. Niaos, V. Germanopoulos and I. Mitaghis were murdered near Tsirlidere. Twenty-six other Greeks were imprisoned, amongst them being G. Tzanetis, I. Koumassonis and the priests loannis Panteleimon and Varlaam.

July 1915. Eighteen (18) Greeks were butchered at Kiosteniou, amongst them being P. Xydias, S. Kapiris, A. Goutaris, N. Valachis, P. Sterghianou and the seventeen-year-old G.Valahis. Seventeen (17) other Greeks were arrested and eleven (11) Greek subjects were expelled.

Dec. 1915. The body of N. Tarnani was found near Kalambaka (of Vourla) horribly mutilated.”[6]

After the First World War: Bombardment of Vourla, 8 January 1919

“Want of security and order was noticeable in places inhabited by Christians. Fanatical Turks, particularly Turks from Crete, were terrorizing the Christians, violating their country houses, robbing or destroying the agricultural implements and other objects in the houses, and killing every Greek they happened to meet. (…)

On the 4th of January 1919, the chief of the police at Vourla, Hussein Effendi, a well know Christian-hater, on learning the hiding-place of H. Mytaras, a deserter from the army, took a policeman and 15 gendarmes, and hastened to catch him. When the accompanying policemen entered the hiding place, he was shot by the deserter, acting in self-defence, and feel dead. The local authorities then gave a political significance to a mere police incident, and besieged the town of Vourla with an important military force, asking that the deserter be given up in the course of half an hour. At the expiration of the appointed time, as the demand was not complied with, the town was bombarded, on the evening of January 8, from all sides by machine-guns and hand-bombs, both by soldiers and by irregulars. The bombardment lasted 24 hours, five innocent Christians were killed and six others were severely wounded. The destruction of the town was prevented through the efforts of the Metropolitain of Ephesus, for the bombardment was stopped on the arrival at the harbour of Vourla of two British torpedo-catchers. The chief of police was given a position in Smyrna, and promoted to the grade of first class officer. The deserter Mataras was killed on the 25th of the same month in the village of Gulbazi outside the town of Vourla.”[7]

Apostolos Anagnostou (b. 1910, Urla – d. 1990, Melbourne)

The following testimony was submitted through online questionnaire of the Greek Genocide Resource Center by Katy Anagnostou. Her father Apostolos was the last of 9 children of Dimitri and Eikaterina Anagnostou.

From which region of the Ottoman Empire were your ancestors from?:

My father was from Vourla (today Urla), near İzmir in Asia Minor.

How did their life change when the Neo-Turks and/or the Kemalists came to power? :

My father and his sister were smuggled [in 1922] by boat to Greece first. He was 12 and his sister 14. The family of 9 were separated, an older brother died in the massacres. This was around the time of the Smyrna fires. The family reunited eventually in Athens. They left with the clothes on their backs. Life in Athens and where they were housed was very basic and hard. They faced a lot of discrimination from the mainland Greeks who regarded them as Turks.

Did anyone within Turkey including Turks try to help them during the genocide?

Dad said there were never any quarrels with his Turkish neighbours, and they got on well. Greeks even respecting their fasting hours during Ramadam.

How did they cope emotionally with their genocide experience? Did it affect the remainder of their life? :

Oh, yes he carried this upheaval with him for the rest of his life.

Did the denial of the genocide by the perpetrator (the successor state of Turkey) affect their ability to form closure?:

They were young and did not understand.

How did they feel about Turkey after the genocide? :

My father always reminisced about the beauty and fertility of his village. He always spoke about the size and sweetness of the figs grown there.

Additional comments:

The stories and scars of my grandparents were left in part in me. That Genocide and aftermath, affected both sides of my family and I have very, very few tangible materials from that time, except that photo and their oral stories.

Excerpted from: http://greek-genocide.net/index.php/quotes/other-testimonies/338-apostolos-anagnostou-vourla?highlight=WyJ2b3VybGEiXQ==