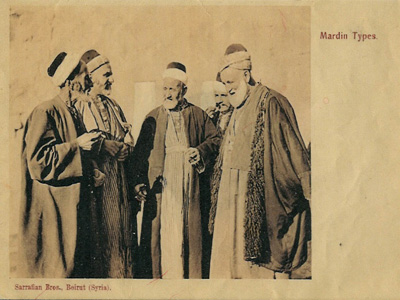

Toponym

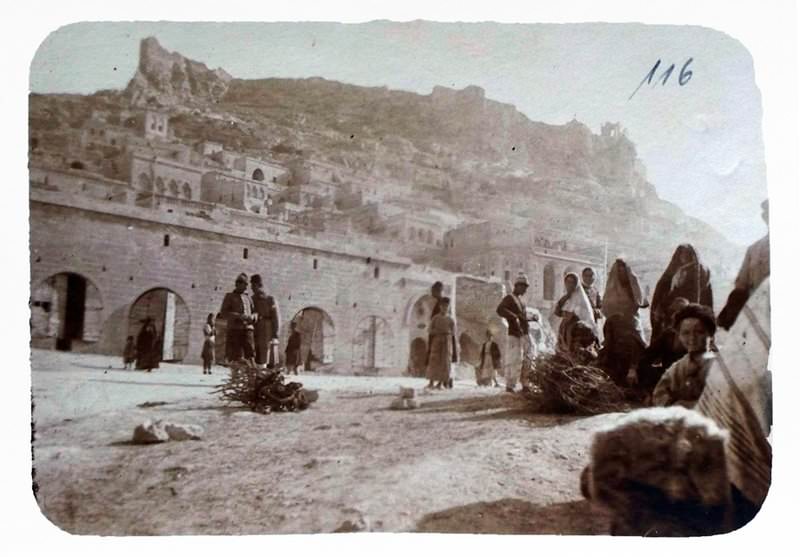

In Aramaic, the town or the Ottoman and Turkish administrative unit of the same name is called Marde or Merdo; in the Eastern Roman Empire, it was called Mardia or Margdis in Greek, then Mardin under the Arabs.

Population

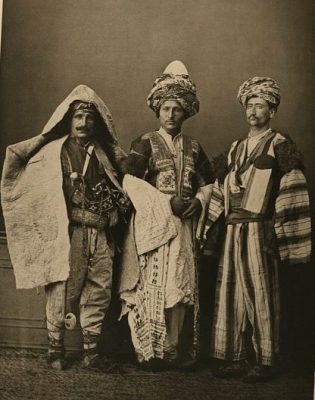

Lying in the heart of Syriac territory, the town of Mardin had a population of 12,609 Orthodox Syriacs and 7,692 Armenians, the vast majority of them Catholic. All were Arabic-speaking.[1] According to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, Armenians lived in two localities, where Armenian communities of the kaza Mardin maintained three churches and four schools with 800 students.[2]

The French scientist Sébastien de Courtois pointed out in his doctoral thesis that there were no firm ethno-religious boundaries between the Syriac and Armenian communities in Mardin: “It should be noted, that several Christian families from Mardin that were counted as belonging to the Catholic Armenians denomination do not automatically derive from the Armenian community in the ethnic sense of the word. Many Syriac families that wanted to convert to Catholicism during the 18th century turned to the Catholic Armenian church since there was no Syriac Catholic clergy in the city. In fact, the notion of ‘nationality’ did not exist between Armenians and Syriacs, since they were all speakers of Arabic, like the Armenians from Aleppo. An ‘Armenian’ could become a ‘Syriac’, and vice versa, by simply changing churches.”[3]

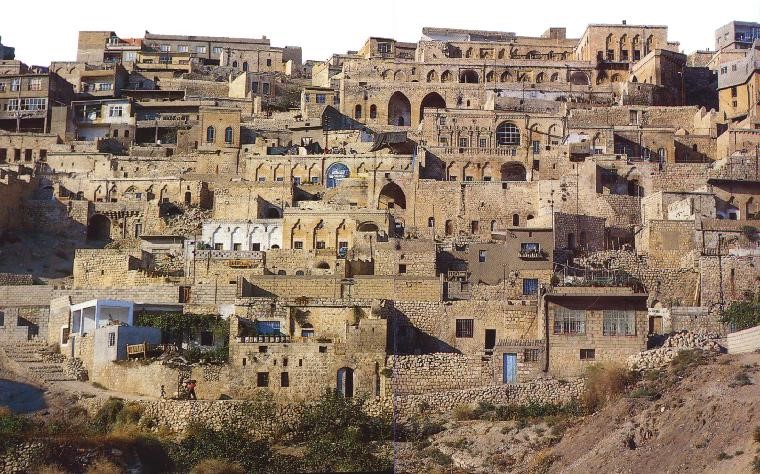

Today, the population of Mardin consists of Turks, Kurds and Arabs as well as the largest Aramaic minority on Turkish territory. In addition to Muslims and Aramaic Christians, several thousand Yazidis lived in Mardin province until a few decades ago. Most of them have now emigrated to Germany, but there is still a small Christian community in Mardin, which is also a bishop’s see. The bishop of Mardin is also the abbot of the monastery Deyrülzafarân.

The Syrian Orthodox Patriarch had his seat at Mardin from 1293. In 1924, he fled to the French mandated territory. From 1850 until the genocide of the Arameans, Mardin was also the seat of the head of the Syriac Catholic Church. After the genocide, the Patriarchate Church building was used by the military until 1988, when the Ministry of Culture bought the building from the Syriac Catholic Church and built the Mardin Museum there in 1995.

History

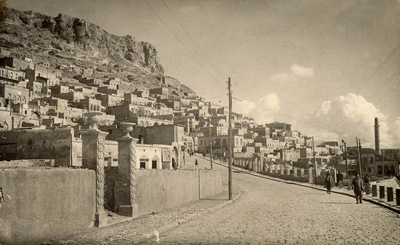

The town and the region were successively under the rule of Arameans, Hurrians, Hittites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Amorites, Persians, Parthians, Romans, Arabs, Kurds, Seljuks and Ottomans. In Assyrian times it was part of Izalla, which was still evident in the early Byzantine name Izala. The first mention under the present name comes from the fourth century A.D. by Ammianus Marcellinus, who refers to the two fortresses Maride and Lorne on the way from Amid (Diyarbekir) to Nisibin.

In 1915/16 most of the Arab, Aramaic and Armenian Christians of the city were indiscriminately killed in the course of the Armenian and Aramaic genocide. For the first time on 15 August 1915, a public trade with Armenian women took place.

Destruction

The Caravans of Death: 1915

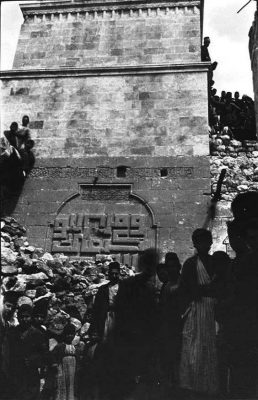

“The first massacre was reported in the beginning of March [1915] near Mardin. (…) A few days later, in Mardin, men belonging to all the Christian denominations, Armenians, Syriacs, Chaldeans and Protestants, were gathered in the town square by order of the governor, and then led to the ‘castle’, his place of residence. Without giving a precise date, Father Armalet mentions that during this pathetic procession through the winding city streets, they were insulted, spit on, and hit with stones by Muslim women and children. (…)

The authorities began to use more radical methods as of June 10, 1915. On that night, Father Armalet’s account speaks of the departure of one of the first convoys of deportees, made up of ‘martyrs’ of all Christian denominations, members of the clergy as well as young men. Where Father Armalet numbers them at 417, Patriarch Rahmani at 470, and Father Simon at 405, they were all murdered just after they left the city ‘through the west gate’ by the soldiers escorting them.

Earlier that evening, all other Christian families had been confined to their homes under orders not to come out for several days. Once the authorities had reached the decision to massacre them the men who had escaped inclusion in the first convoy were again rounded up in the town square amid the bloodthirsty screams of the populace, ‘You are going to die like your Christ!’ The tension reached its peak when other priests and bishops were added to their numbers. The convoy left the city on foot at the end of the day, after the authorities had informed them that they were to go to Diyarbakir for ‘judgment’, to use Father Armalet’s term. What were their crimes? No one ever returned from the convoy. (…)

The day after the first convoy, the Turks arrested Syriac Catholics to form ‘a second caravan of death’. ‘Now 370 Christians of different denominations were put in prison and mistreated.’ Several days later, on June 14, 70 of them were singled out, 75 according to Father Simon, and led on foot towards Diyarbakir, where they met their end along the way, in the village of ‘Setmane’. (…)

Father Armalet says that another convoy was formed on June 21, 1915. (…) The governor summoned the remaining priests as well as several notables of all denominations and accused them of ‘working against the government’. The non-Armenians were asked ‘to raise their hands’, so that they could be sent home. This third ‘caravan of death’ left the city in the same way as the earlier ones and was eliminated near the village of ‘Hafkur’. The number of victims was not recorded. Patriarch Rahmani also describes a convoy leaving around the same time, before June 29, made up of the prison populations ‘of different denominations. Then, one morning, they had them leave the city through the gate called ‘the wall gate’; some of them were massacred not far from the city, others met the same fate near the village of Dara [south west of Mardin].’

They were then thrown into deep wells that had once been King Darius’ old prisons. (…)

The attacks intensified against Christian communities over the course of July 1915. Women who had until then escaped the raids were now the main victims.

On July 2, a new ‘caravan of death’ left Mardin. Numbering 600, they were killed just as they left the city. On July 15, all Christian homes were sacked. The soldiers extorted money from the richest families in exchange for promise of leniency. (…) The Syriac community was ordered to pay 2,000 Turkish pounds to the city’s governor. It seems that the promises of leniency were not respected, for the next day, the women, who Father Armalet said were of all denominations, were gathered in the public square in order to form a convoy. They left the city on foot during the night of July 16-17, 1915, ‘the soldiers undressed them outside the city and massacred them in small groups.’ (…)

The massacre continued until July 19, and was completed by the massacre of the victims of new convoys coming ‘from Diyarbakir’ and ‘from Armenia’, that were made up essentially of Armenians. On August 2, ‘a second caravan of women of all denominations is brought to Aleppo. A small number of them were killed along the way.’

The convoys of deportees coming from the Armenian plateau towards the Syrian desert, the location to which, in theory, the population was to be displaced, were forced to pass through the Mardin vicinity. On the evening of July 1, a convoy of Armenian women numbering more than 2,000 arrived at Mardin.

‘It was the first image of the transmigrations in our region. Thirty-five days of walking and starving, dressed in rags with messy hair, gloomy, numb, barefoot, tanned from the sun, eyes staring as if haunted by distant visions of recent carnage. On July 5th, another arrival, more than 3,000 Armenian women deported for the same reason, under the same conditions, and to the same destination.’

The convoys were then routed towards Ras-ul-Ain, 18 hours away by foot, near the new railroad, where the luckiest were boarded into a train for Aleppo. This city received a large number of Syriac families coming from Urfa who had no trouble integrating afterwards. Few Syriac families from Tur Abdin were able to seek refuge there because of its great distance. The Syrian city of Al-Qamishli played this role during the protective period of the French mandate.”

Excerpted from: Courtois, Sébastien de: The Forgotten Genocide: Eastern Christians, the Last Arameans. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2004, pp. 166-173

In an estimate presented at the Paris Peace Conference (1919), the Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate put the number of massacred Syriac Orthodox Christians in the kaza Mardin at 5,815 and the number of destroyed villages at 8.[4]

Bishop Ignatius Maloyan: Armenian Catholic Martyr and Blessed

Ignatius (Shourallah – Շուրալլահ), son of Melkon and Faridé, was born in 1869, in Mardin, Turkey. His parish priest, noticed in him signs of a priestly vocation, so he sent him to the convent of Bzommar-Lebanon; he was fourteen years old.

After finishing his superior studies in 1896, the day dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, he was ordained priest in the Church of Bzommar convent, became a member of the Bzommar Institute and adopted the name of Ignatius in remembrance of the famous martyr of Antioch. During the years 1897-1910, Father Ignatius was appointed as parish priest in Alexandria and Cairo, where his good reputation was wide-spread.

His Beatitude Patriarch Boghos Bedros XII appointed him as his assistant in 1904. Because of a disease that hit his eyes and suffocating difficulty in breathing, he returned to Egypt and stayed there till 1910.

The Diocese of Mardin was in a state of anarchy, so Patriarch Sabbaghian sent Father Ignatius Maloyan to restore order. On 22 October 1911 the Bishops’ Synod assembled in Rome elected Father Ignatius Archbishop of Mardin. He took over his new assignment and planned on renewing the wrecked Diocese, encouraging especially the devotion to the Sacred Heart.

Unfortunately, at the outbreak of the First World War, the Armenians resident in Turkey (which was allied with Germany) began to endure unspeakable sufferings. In fact, 24 April 1915 marked the beginning of a veritable campaign of extermination. On 30 April 1915, the Turkish soldiers surrounded the Armenian Catholic Bishopric and church in Mardin on the basis that they were hide-outs for arms.

At the beginning of May, the Bishop gathered his priests and informed them of the dangerous situation. On 3 June 1915 Turkish soldiers dragged Bishop Maloyan in chains to court with twenty seven other Armenian Catholic personalities. The next day, twenty five priests and eight hundred and sixty two believers were held in chains. During trial, the chief of the police, Mamdooh Bek, asked the Bishop to convert to Islam. The bishop answered that he would never betray Christ and His Church. The good shepherd told him that he was ready to suffer all kinds of ill-treatments and even death and in this will be his happiness.

Mamdooh Bek hit him on the head with the rear of his pistol and ordered to put him in jail. The soldiers chained his feet and hands, threw him on the ground and hit him mercilessly. With each blow, the Bishop was heard saying “Oh Lord, have mercy on me, oh Lord, give me strength”, and asked the priests present for absolution. With that, the soldiers went back to hitting him and they extracted his toe nails.

On 9 June his mother visited him and cried for his state. But the valiant Bishop encouraged her. On the next day, the soldiers gathered four hundred and forty seven Armenians. The soldiers along with the convoys took the desert route.

The bishop encouraged his parishioners to remain firm in their faith. Then all knelt with him. He prayed to God that they accept martyrdom with patience and courage. The priests granted the believers absolution. The Bishop took out a piece of bread, blessed it, recited the words of the Eucharist and gave it to his priests to distribute among the people.

One of the soldiers, an eye witness, recounted this scene: “That hour, I saw a cloud covering the prisoners and from all emitted a perfumed scent. There was a look of joy and serenity on their faces”. As they were all going to die out of love for Jesus. After a two-hour walk, hungry, naked and chained, the soldiers attacked the prisoners and killed them before the Bishop’s eyes. After the massacre of the two convoys came the turn of Bishop Maloyan.

Mamdooh Bek then asked Maloyan again to convert to Islam. The soldier of Christ answered: “I’ve told you I shall live and die for the sake of my faith and religion. I take pride in the Cross of my God and Lord”. Mamdooh got very angry, he drew his pistol and shot Maloyan. Before he breathed his last breath he cried out loud: “My God, have mercy on me; into your hands I commend my spirit.”

Source: http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20011007_beat-maloyan_en.html

BEATIFICATION OF 7 SERVANTS OF GOD

HOMILY OF POPE JOHN PAUL II

Sunday 7 October 2001

(…)

2. Archbishop Ignatius Maloyan, who died a martyr when he was 46, reminds us of every Christian’s spiritual combat, whose faith is exposed to the attacks of evil. It is in the Eucharist that he drew, day by day, the force necessary to accomplish his priestly ministry with generosity and passion, dedicating himself to preaching, to a pastoral life connected with the celebration of the sacraments and to the service of the neediest. Throughout his existence, he fully lived the words of St Paul: “God has not given us a spirit of fear but a spirit of courage, of love and self control” (II Tim 1,14. 7). Before the dangers of persecution, Bl. Ignatius did not accept any compromise, declaring to those who were putting pressure on him, “It does not please God that I should deny Jesus my Saviour. To shed my blood for my faith is the strongest desire of my heart”. May his example enlighten all those who today wish to be witnesses of the Gospel for the glory of God and for the salvation of their neighbour. (…)

Christian Orphans in Mardin, 1915-1921

By order of the Minister of War, Ismail Enver, an orphanage was founded in mid-1916 because there are reported to have been countless orphans on the streets of the city. From Mardin the children were distributed to other institutions. This redistribution had a method and should serve to permanently uproot the children from their familiar surroundings.[5]

The German military doctor Theo Malade mentions in his war memoirs, published close to the event, the transport of 50 Armenian orphans to Mardin at the beginning of July 1917:

“Two of the lorries, which also transported me back from Diyarbekir, transported fifty emaciated Armenian children aged five to ten years to Mardin under the direction of a Yusbaşı, a captain. There they are passed on – somewhere where they perish from beatings, heat, hunger. The children received only a sip of milk at four o’clock in the morning when they left. They sit huddled and crouched on the floor of the wagon. As soon as one of them wants to get up, the Baş-Çavuş, the sergeant, taps more or less gently with a stick on the head. I take the stick from him and beat him with it. After a few hours we stop at a spring water. The shaken, glowing children are covered with dust as thick as a finger and are whining and asking: ‘Water!’ The Yusbaşı orders silence. Our soldiers grit their teeth with rage. I call him ‘cattle‘. I order as a doctor that the children dismount immediately and get watered. (…) My driver told me, gritting his teeth, that in winter he often had to do this kind of ‘corpse driving’ of children. I drove the last ten kilometers ahead in a passenger car and heard nothing more from the children. I just watched: when Mardin appeared in the distance with the torn castle and the rock walls, the silent crying stopped – this terrible, silent crying of children. They all rose and held on to the sides of the lorry, despite the violent knocks, and stared with a strange expression of expectation and horror at the place that was to receive them. I’ve seen it before with cattle driven to the slaughterhouse and smelling the blood.” [6]

After World War I, and according to contemporary eyewitness accounts, Mardin remained to be a place of horror where even foreign missionaries did not have the influence to protect orphans:

“A messenger from Mardin who reached Mosul reported that forty boys were taken forcibly, possibly to be slaughtered, from a missionary orphanage. Girls recovered from Muslim homes were carried off for a night from mission quarters and returned the next day.”[7]