Administration

The sancak comprised six kazas: Erzincan/Yerznka, Kemah/Gamakh, Kuruçay, Refahiye/Gerjanis, Bayburt/Baberd, and Ispir/Sper.

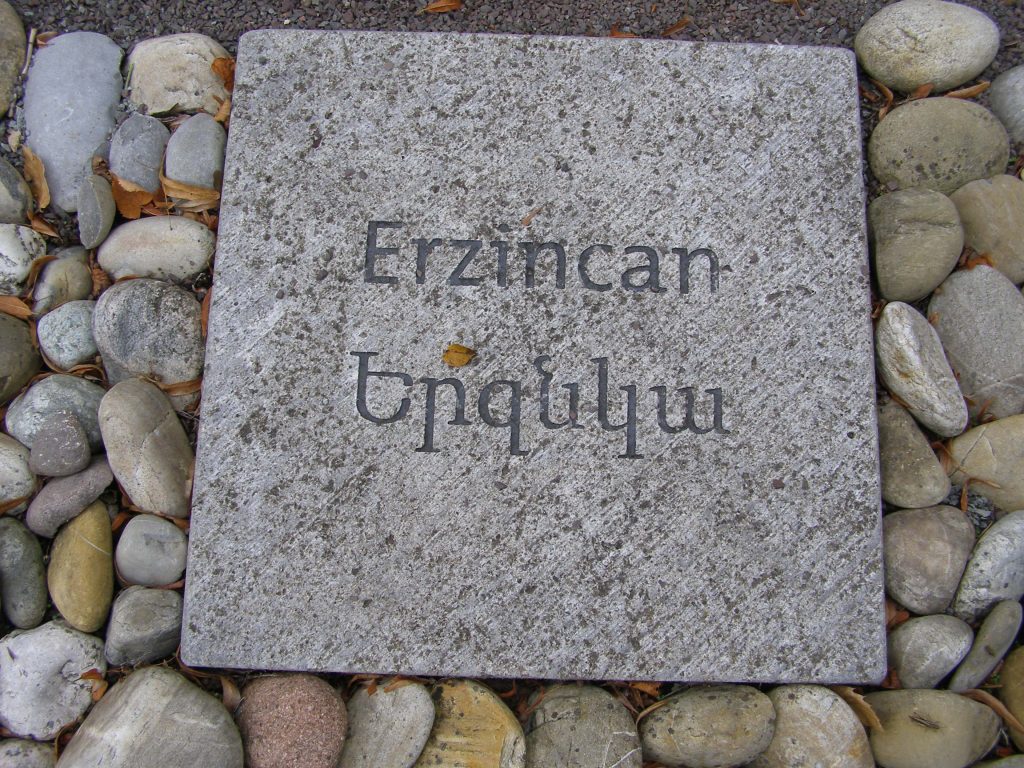

Toponym

Previously called Yerez or Yeriza, the city of Erzincan was known in ancient times as Acilisene (Grk.: Ἀκιλισηνή – Akilisini) and for a while Justinianoupolis in honour of Emperor Justinian I. In the Armenian language, the 5th-century Life of Mashtots called it Yekeghiats. In the more recent past it was known in Armenian as Երզնկա (Yerznka).

Population

According to the Ottoman census of 1893 the overall population of the sancak Erzincan was 107,100; of these, 85,900 were Muslims, 19,000 Armenian Apostolic, 200 Protestants and 2,000 Greek Orthodox.

According to the French-Armenian scholar Raymond Kévorkian, basing on the statistics of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, there lived 37,612 Armenians in 66 localities of the sancak of Erzincan before 1915. They had 103 churches, 35 monasteries, and 61 schools with more than 5.000 pupils.[1]

History

In the settlement of Erez, at a yet unidentified site, there was a pre-Christian shrine dedicated to the Armenian virgin goddess Anahit. A text of Agathangelos reports that during the first year of his reign, King Trdat of Armenia went to Erez and visited Anahit’s temple to offer sacrifice. He ordered Gregory the Illuminator (Grigor Lusavorich), who was secretly a Christian, to make an offering at its altar. When Gregory refused, he was taken captive and tortured, starting the events that would end with Trdat’s conversion to Christianity some 14 years later. After that conversion, during the Christianization of Armenia, the temple at Erez was destroyed and its property and lands were given to Grigor Lusavorich. It later became known for its extensive monasteries.

It is hard to tell when Acilisene became a bishopric. The first whose name is known is of the mid-5th century: Ioannes, who in 459 signed the decree of Patriarch Gennadius I of Constantinople against the simoniacs. Georgius or Gregorius (both forms are found) was one of the Fathers of the Second Council of Constantinople (553), appearing as “bishop of Justinianopolis”. Until the 10th century, the diocese itself appears in none of the Notitiae Episcopatuum. At the end of that century, they present it as an autocephalous archdiocese, and those of the 11th century present it as a metropolitan see with 21 suffragans. This was the time of greatest splendor of Acilisene, which ended with the decisive defeat of the Byzantines by the Seljuk Turks at the Battle of Man(t)zikert in 1071.

In 1071 Erzincan was absorbed into the Mengüçoğlu under the Seljuk Sulëiman Kutalmish. Marco Polo, who wrote about his visit to Erzincan, said that the “people of the country are Armenians” and that Erzincan was the “noblest of cities” which contained the See of an Archbishop. In 1243 it was destroyed in fighting between the Seljuks under Kaykhusraw II and the Mongols. However, by 1254 its population had recovered enough that William of Rubruck was able to say an earthquake had killed more than 10,000 people. During this period, the city reached a level of semi-independence under the rule of Armenian princes. In the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries the Beylik of Erzincan was one of independent states emerging after the battle of Kösedağ (1243) and the disintegration of the state of the Ilkhanid Mongols.

Erzincan was one of the most pivotal towns in Safavid history. It was there, in the summer of 1500, that about 7,000 Qizilbash forces, consisting of the Ustaclu, Shamlu, Rumlu, Tekelu, Zhulkadir, Afshar, Qajar and Varsak tribes, responded to the invitation of Ismail I, who would aid in him establishing his dynasty.

Battle of Erzincan

The Battle of Erzincan took place during the Caucasus Campaign of the First World War. In 1916 Erzincan was the headquarters for the Ottoman Third Army commanded by Kerim Pasha. The Russian General Nikolai Yudenich led the Russian Caucasus Army who captured Mama Hatun (Tercan) on 12 July 1916. They then gained the heights of Naglika and took an Ottoman position on the banks of the Durum Durasi river, with their cavalry breaking through the Boz-Tapa-Meretkli line. They then advanced on Erzincan arriving by 25 June 1916 and taking the city in two days. The city was relatively untouched by battle and Yudenich seized large quantities of supplies. Despite the strategic advantages gained from this victory, Yudenich made no more significant advances and his forces were reduced due to Russian reverses further north.

Colonel Kâzım Karabekir was appointed the commander of the First Caucasian Army Corps. Aware of the withdrawal of the Russian Army following the Russian Revolution, they retook Erzincan in February 1918.

Destruction

“The sancak of Erzincan, which, with its 66 Armenian villages and a total Armenian population of 37,612,was rather sparsely settled, played an important role as a zone of transit for convoys of deportees from the vilayet, while the district’s Kemah gorge served as a killing field. The main organizers of the massacres here were the mutesarif of the sancak, Memduh Bey, and the parliamentary deputy from Kemah, Halet Bey. They were backed up by Muhtar Bey, the commander of the gendarmerie of Erzincan, Mecid Bey, the mutesarif’s secretary, and the commanders of the çetes of the Special Organization, Ziya Beg, Adıl Güzelzade Şerif, Nazıf Bey, Nazıf’s nephew Mazhar Bey, Eçzaci Mehmed, Kurd Arslan Bey, a cousin of Halet Bey’s, and Kemal Vanlı Bey. In a written deposition submitted to the Mazhar Commission, General Vehib Pasha, who succeeded Mahmud Kвmil at the head of the Third Army, stated that the officers of the gendarmerie received the order to deport the Armenians from ‘Memduh Bey, the former mutesarif of Erzincan,’ and that “those who committed the murders had received their instructions from Dr. Bahaeddin Şakir Bey.’

Both the general mobilization and requisitions were carried out with special rigor in this sancak. A witness reports that, when the requisitions were made in her village, which had 300 Armenian and 50 Turkish households, ‘it was plain that not much at all was taken from the Turks.’ As elsewhere, the April 1915 order to collect arms was executed with extreme violence and accompanied by torture, bastinados, and arrests. None of the villages on the plain of Erzincan were spared these operations.

On Sunday, 16 May, the last service was celebrated in the cathedral of Erzincan. In his sermon, Father Mesrob informed the population that the government had decided to deport it and that the most affluent 16 families had to go to Konya. On Tuesday, 18 May, the Der-Serian, Papazian, Boyitian, and Susigian families, among others, were deported. On 21 May, they were followed by 60 other families whose names figured on a list drawn up by the local authorities. A few days later, the Armenian bishopric of Erzincan received telegrams, sent from Eğin, announcing that these families had arrived there safe and sound.

In Erzincan, the authorities had confiscated three of the city’s four churches, leaving Surp Prgich [Surb Prkich – Holy Savior] Cathedral to the Armenians. According to Kurken Keserian, Erzincan’s Armenian quarter was now transformed into a veritable chaos; its schools and churches were systematically pillaged.

A week before the deportation of the Erzincan Armenians, Halet Bey had the city’s notables arrested; among them were Krikor Chayan and Apkar Tashjian. These notables were massacred in Kemah and Sansar Dere soon after their arrest.

On the evening of 23 May, the kaimakam of the kaza, Memduh, arrived on the plain of Erzincan at the head of a group of gendarmes, çetes, and Turkish peasants from the surrounding villages, a force of some 12,000 armed men. They surrounded the villages and monasteries. A few young men managed to flee to the mountains, but the men from the households on the plain were methodically killed on Sunday, 23 May, and Tuesday, 25 May, while the women and children were sent to Erzincan’s Armenian cemetery.

According to eyewitnesses, surprise attacks were launched on the villages after the forces that had been mobilized for this operation had carefully isolated them from each other. The men were then executed in small groups – they were either shot or had their throats cut in trenches that had been dug in advance.

Once this operation had been terminated, the authorities began, on Tuesday, 25 May, to concentrate the Armenian population of Erzincan in the Armenian cemetery of Kuyubaşi, a quarter of an hour from the city. By the evening of 27 May, the whole population of the city and nearby villages had been interned there, where they were guarded by çetes.

The Armenians of the Surmen neighborhood, who had a reputation for unruliness, were the only exception: they were to be dealt a special fate. The deportees were sorted into groups by neighborhood. Men between 40 and 50 were separated from the others and massacred by the gendarmes and çetes.

On 28 May, under the supervision of the parliamentary deputy Halet Bey, the remaining deportees were set marching at one-hour intervals in little groups down the road that led to Kemah; the aim was to prevent visual contact between the different groups. The caravan in which one survivor found himself got as far as the khan belonging to Halet’s brother Haci Bey; there the squadrons of çetes were reinforced by Kurds from seven villages in the Ceferli district.

Deportees from the villages of Karni, Tortan, and Komar were integrated into the convoy. Further on, this convoy, escorted by Captain Mustafa Bey, was attacked by a squadron of çetes under the command of Demal Vanlı Bey, Kürd Aslan Bey, and Mazhar Bey, a cousin of Halet’s; they extorted large sums from the deportees and carried off six of the prettiest young women.

The gorge that lay three hours distant from the city and extended as far as Kemah, eight hours away, became the graveyard of the deportees from Erzincan and its plain, who were thrown into it. Only a few women who had been abducted and taken to Turkish villages in the area temporarily cheated death.

One by one, the groups of deportees piled into the Kemah gorge, actually a series of gorges that extend over an area that it takes four hours to traverse on foot. It was as if the Armenians were caught in a trap from which there was no escape: on the one side was the turbulent Euphrates and, on the other, the cliffs of the Mt. Sebuh mountain chain.

As the deportees entered the gorge, they were stripped of their belongings by çetes under the command of Jafer [Cafer] Mustafa Effendi, who had squadrons of the Teşkilât-ı Mahsusa under his orders.

Deeper in the gorges, veritable slaughterhouses had been set up, in which some 25,000 people were exterminated in one day. Hundreds of young women and children joined hands and leaped into the void together. A few young women even dragged çetes who were trying to rape them down into the waters of the Euphrates with them.

At regular intervals, the butchers clambered down to the narrow banks of the river in order to finish off wounded people who had not been swept away by the current. Almost all the convoys of deportees from Ispir, Hınis, Erzerum, Tercan, and Pasin passed through these gorges, one of the main killing fields regularly used by the çetes of the Special Organization.

The fate of very young children seems to have differed from that of all the others. A conscript employed, along with his colleague Garabed Vartabedian, as the secretary of a captain in the army noticed that Turks were picking up ‘abandoned’ children in the streets of Erzincan and taking them home.

The next day, the same witness obtained permission to leave his barracks and go to his home in the city’s Armenian quarter. On the way, he passed by the Armenians’ municipal park, where 200 to 300 children between the ages of two and four had been gathered; they had been given neither food nor water, and some were already dead.

A pharmacist from Erzerum who was serving in the Erzincan garrison, Dikran Tertsagian, told our witness that six-month-old or seven-month-old babies were less fortunate: they were being collected in sacks in the villages of the plain and thrown into the Euphrates.

In the week following the massacres, policemen and gendarmes hunted down people hiding in the orchards and fields of the plain of Erzincan. In one house, two young men fought off 100 gendarmes, killing seven of them before being burned alive.

On Monday, 14 June, there were still 800 Armenians in Erzincan who were employed in the army workshop located in the outskirts of the city; another 150 Armenians were working as street sweepers, while three more were serving as nurses or nurses’ aids in the military hospital. They did not know what had become of their families. Other men from the region who had been arrested before the deportation were still rotting in jail; the authorities had led them to believe that the deportees had been transferred to Mosul in perfect safety.

It was on this day, 14 June, that Mamud Kâmil ordered that all Armenian conscripts working in the hospitals, military workshops, and street-sweeping brigades be confined in the Erzincan barracks, to be guarded by çetes. A few of these conscripts remained there; the others were gradually, day by day, tied together in small groups and led off. They were conducted eastwards to the Cerbeleg Bridge, where they were shot and thrown into trenches that had been dug in advance.

The conscripts from the region who were working in the amele taburis [labor battalions] were massacred in two different places. Approximately 5,000 of them were slaughtered in a plain lying a short distance to the east of Erzincan; their bodies were thrown into mass graves.

A second group of about the same size was slain in the Sansar gorge, located eight hours east of Erzerum on the boundary of the kaza of Tercan, at the mouth of the mountain pass. It seems that 15,000 old people from the vilayet were also put to death there.

According to a conscript who survived the massacre, when the Russians arrived in the area in spring 1916, there were only a few dozen women left; they had been taken into the households of the gendarmes and the dignitaries with the heaviest responsibility for the massacres, now having finally been given permission to ‘marry’ Armenian women.

Also left alive were some 300 indispensable craftsmen, such as Avedis Kuyumjian and the seven members of his family, and Nshan Buludian and the six members of his (the former was a goldsmith, the latter a tailor). These men directed state workshops. There were also some 50 doctors on the staff of the hospital in Erzincan, among them Sarkis Sertlian, an eye doctor from Constantinople, and Dr. Mikayel Aslanian of Harput. The authorities sent Aslanian on to Harput and Sivas just before Erzincan fell to the Russians.”[2]