The Ottoman province of Konya included the whole, or parts of, the ancient regions of Pamphylia, Pisidia, Phrygia, Lycaonia, Cilicia and Cappadocia. Konya province, the largest in Turkey, has important mineral resources.

Toponym

Under the ancient Greek name of Iconion (Latinized: Iconium), Konya is mentioned as one of the cities of ancient Phrygia in classical antiquity and during the medieval period. Ikónion is the Hellenization of an older Luwian name Ikkuwaniya.

Some explain the name Ikónion as a derivation from εἰκών (icon), as an ancient Greek legend ascribed its name to the ‘eikon’ (image), or the ‘gorgon’s (Medusa’s) head’, with which Perseus vanquished the native population before founding the city.

According to the Suda, Perseus after he married Andromeda founded the city and called it Amandra (Ἄμανδραν) and the city had a stele depicting the Gorgon. The city later changed the name to Ikonion because it had the depiction (ἀπεικόνισμα) of the Gorgon.

Once incorporated into the Roman Empire, under the rule of emperor Claudius, the name Iconium was changed to Claudioconium, and during the rule of emperor Hadrianus to Colonia Aelia Hadriana.

In some historic English texts, the city’s name appears as Konia or Koniah.

Administration

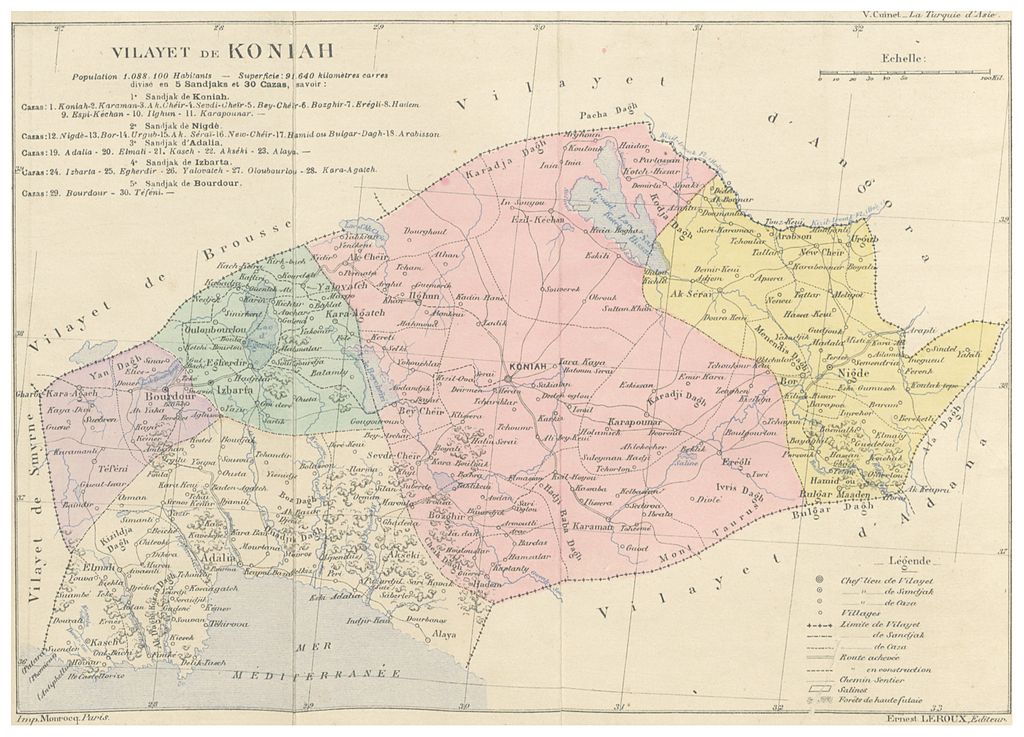

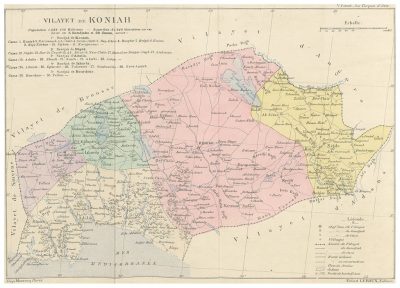

Between 1483 and 1864, Konya was the administrative capital of Karaman Eyalet. During the Tanzimat period, as part of the vilayet system introduced in 1864, Konya became the seat of the larger Vilayet of Konya which replaced Karaman Eyalet by adding the western half of Adana, and part of southeastern Anatolia.

Covering a territory of 91,620 sqkm, the Ottoman Vilayet of Konya comprised the five sancaks Konya, Niğde, Isparta, Burdur, and Adalya (Tekke/Elmalı), subdivided into 30 kazas.

Population

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the overall population of the province as 1,088,100. As of 1920, less than 10% of the population was described as being Christian, with majority of Christian populations – Greeks and Armenians – by the Mediterranean Sea. According to the statistics of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, in 1914 the Armenian population of the province was around 24,000 (nearly 14,000 according to the Ottoman statistics).[1] The Greek-Orthodox Diocese of Konya (Konia) consisted of 42 communities with 50,800 Greek Orthodox inhabitants.[2]

At an early date, daily increasing terrorism had become manifest in this Diocese, whose Government officials persecuted in divers manners the Christians, and excited the Moslem element against them.

The population of the province was for the most part agricultural and pastoral. The only industries were carpet-weaving and the manufacture of cotton and silk stuffs. There were mines of chrome, mercury, sulphur, cinnabar, argentiferous lead and rock salt. The principal exports were salt, minerals, opium, cotton, cereals, wool and livestock; and the imports cloth-goods, coffee, rice and petroleum. The vilayet was traversed by the Anatolian railway, and contained the railhead of the Ottoman line from Smyrna.

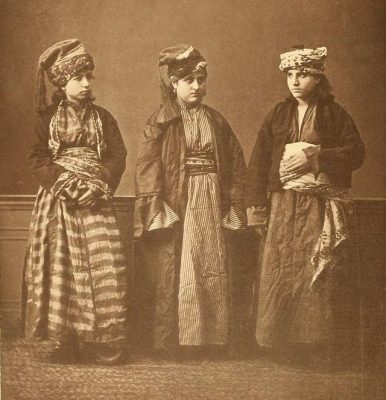

Karamanlides – Καραμανλήδες – Karamanlılar

“Ethnic identity can be a slippery fish! Take the case of the Karamanlides, whom everyone agrees were named after the town of Karaman, in what is now the country of Turkey. Karaman was the first Turkish kingdom to use Turkish as the official language. The Karamanids themselves, a Turkic tribe from the Azerbaijan area, overran the region in 1230. The region at that time had been part of the Greek Byzantine Empire, populated by Christians who spoke Greek and whose religion was Greek Orthodox. By 1300, various Turkic tribes had conquered most of the former Byzantine Anatolia. Each tribe had its little fiefdom.“[3]

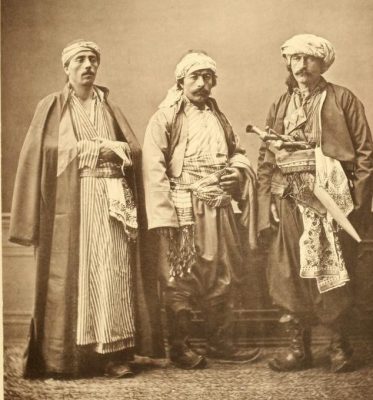

The Karamanlides (Grk.: Καραμανλήδες; Trk.: Karamanlılar), or simply Karamanlis, are a Greek Orthodox, Turkish-speaking people native to the Karaman and Cappadocia regions of Anatolia. Today, a majority of the population live in Greece, though there is a sizeable diaspora in Western Europe and North America.

The term Karamanlides is geographical, deriving from the 13th century Kingdom of Karaman. Originally the term would only refer to the inhabitants of the town of Karaman or from the region of Karaman.

Karamanlı writers and speakers were expelled from Turkey as part of the forcible Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923. Some speakers preserved their language in the diaspora. The writing form stopped being used immediately after the Turkish state adopted the Latin alphabet.

The origins of Karamanlides are debated and not conclusive. The historian Speros Vryonis gives two basic theories on the origins of the Karamanlides. According to the first, they are the remnants of the Greek-speaking Byzantine population which, though it remained Orthodox, was linguistically Turkified. The second theory holds that they were originally Turkish soldiers which the Byzantine emperors had settled in Anatolia in large numbers and who retained their language and Christian religion after the Turkish conquests.

The Karamanlides printed books, particularly the bible, in Turkish language and chanted hymens in Karamanlidika despite their neighbourhoods also having Greek-speaking communities. The distinct culture that developed among the Karamanlides blended elements of Orthodox Christianity with a Turkish-Anatolian culture that characterized their willingness to accept and immerse themselves in foreign customs. From the 14th to the 19th centuries, they enjoyed an explosion in literary refinement. Karamanli authors were especially productive in philosophy, religious writings, novels, and historical texts. Their lyrical poetry in the late 19th century describes their indifference to both Greek and Turkish governments, and the confusion which they felt as a Turkish-speaking people with a Greek Orthodox religion.

Upon seeing Karamanlides’ requests to stay in Turkey, the Turkish government tried to cut a deal for them to be exempt from the population exchange however this was not accepted.

Many Karamanlides were forced to leave their homes during the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. Early estimates placed the number of Turkish-speaking Orthodox Christians expelled from central and southern Anatolia at around 100,000. However, Stevan K. Pavlowitch says that the Karamanlides were numbered at around 400,000 at the time of the exchange.

Upon arrival in Greece, Karamanlides faced many instances of discrimination by the local Greek population. They were called ‘tourkosporos’, a slur meaning Turkish seed. During Metaxas’ rule, they were punished for speaking and identifying as Turkish, the use of languages other than Greek were banned. “Following this alienation, they went on to establish villages and neighborhoods named after places they came from in Anatolia, adding ‘nea’ (new) in front of them. Always considering Anatolia their homeland, the communities continued to preserve their language and culture without mixing with local Greeks.”[4]

History

Ancient history

Excavations have shown that the region was inhabited during the Late Copper Age, around 3000 B.C. The city came under the influence of the Hittites around 1500 B.C. Later it was overtaken by the Sea Peoples in around 1200 B.C.

The Phrygians established their kingdom in central Anatolia in the 8th century B.C. The region was overwhelmed by Cimmerian invaders c. 690 B.C. It later became part of the Persian Empire, until Darius III was defeated by Alexander the Great in 333 B.C. Alexander’s empire broke up shortly after his death and the town of Iconium came under the rule of Seleucus I Nicator. During the Hellenistic period the town was ruled by the kings of Pergamon. As Attalus III, the last king of Pergamon, was about to die without an heir, he bequeathed his kingdom to the Roman Republic.

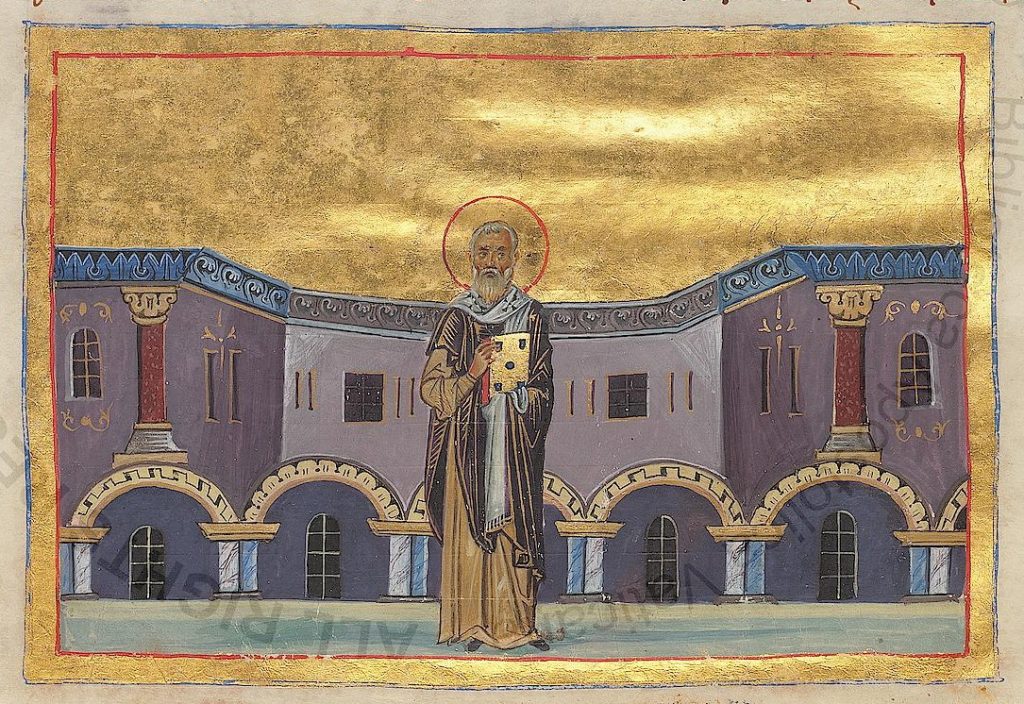

According to the Acts of the Apostles, the apostles Paul and Barnabas preached in Iconium during their first Missionary Journey in about 47–48 A.D., having been persecuted in Antioch, and Paul and Silas probably visited it again during Paul’s Second Missionary Journey in about 50. Their visit to the synagogue of the Jews in Iconium divided the Jewish and non-Jewish communities between those who believed Paul and Barnabas’ message and those who did not believe, provoking a disturbance during which attempts were made to stone the apostles. They fled to Lystra and Derbe, cities of Lycaonia. This experience is also mentioned in the Second Letter to Timothy. The city became the seat of a bishop, which in ca. 370 was raised to the status of a metropolitan see for Lycaonia, with Saint Amphilochios as the first metropolitan bishop.

In Christian legend, based on the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla, Iconium was also the birthplace of Saint Thecla, who saved the city from attack by the Isaurians.

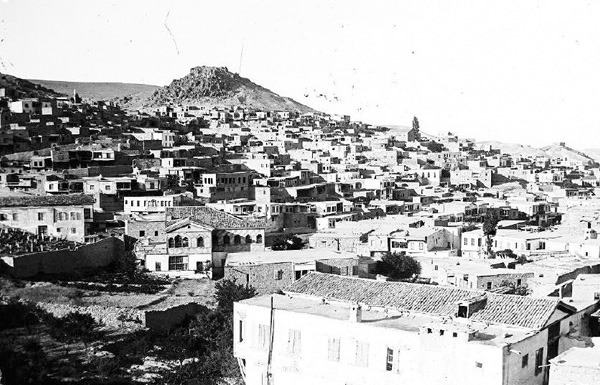

Under the Byzantine Empire, the city was part of the Anatolic Theme. During the 8th to 10th centuries, the town and the nearby (Caballa) Kaballah Fortress (Trk.: Gevale Kalesi) were a frequent target of Arab attacks as part of the Arab–Byzantine wars.

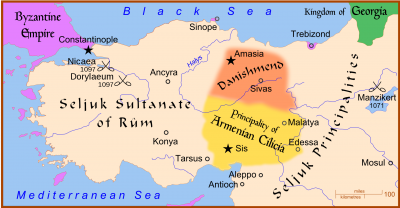

Seljuk and Karamanid eras

The Seljuk Turks first raided the area in 1069, but a period of chaos overwhelmed Anatolia after the Seljuk victory in the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and the Norman mercenary leader Roussel de Bailleul rose in revolt at Iconium. The city was finally conquered by the Seljuks in 1084. From 1097 to 1243 it was the capital of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. It was briefly occupied by the Crusaders Godfrey of Bouillon (August 1097), and Frederick Barbarossa (May 18, 1190) after the Battle of Iconium (1190). The area was re-occupied by the Turks after the crusaders left.

Konya reached the height of its wealth and influence in the second half of the 12th century when the Seljuk sultans of Rum also subdued the Anatolian beyliks to their east, especially that of the Danishmends, thus establishing their rule over virtually all of eastern Anatolia, as well as acquiring several port towns along the Mediterranean (including Alanya) and the Black Sea (including Sinop) and even gaining a momentary foothold in Sudak, Crimea. This golden age lasted until the first decades of the 13th century.

Many Persians and Persianized Turks from Persia and Central Asia migrated to Anatolian cities either to flee the invading Mongols or to benefit from the opportunities for educated Muslims in a newly established kingdom.

Following the fall of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate in 1307, Konya became the capital of Karamanids, a Turkish beylik, which lasted until 1322 when the city was captured by the neighbouring Beylik of Karamanoğlu. In 1420, the Beylik of Karamanoğlu fell to the Ottoman Empire and, in 1453, Konya was made the provincial capital of Karaman Eyalet.

Destruction

Deportations of Armenians to and from the province of Konya

Early on, Konya province became a deportation area for Armenians of the mutesarriflik (sancak) of Izmit and the provinces of Edirne and Aydın. “During the deportations of summer and fall 1915, all the deportees from Thrace and western Anatolia who were following the Adapazar-Konya-Bozanti route to exile in Syria were concentrated in the province of Konya. Konya’s train station, which lay on the last trunk of the railway, also served as a transit or regrouping center for the deportees.”[5]

From 8-20 April 1915, 18,000 Armenians from Zeytun and nearby locales were deported in several convoys—6,000 towards Konya-Ereğli, then Sultaniye; 5,000 to Aleppo; and the remainder to Rakka.[6] In the beginning of May 1915, they were followed by 50 Armenian notables from the town of Adapazar (mutessarifat of Izmit), who were arrested and deported to Sultaniye (province of Konya) and Koçhisar.[7] On 18-19 July 1915 the Armenian village Arslanbeg in the same mutessarifat of Izmit was surrounded by 200 soldiers and gendarmes. The following morning the deportations started; over 2,000 people were deported via Eskişehir, Konya, and Bozantı, and were then dispersed to Rakka, Meskene, Der el-Zor, Mosul, or Baghdad.[8] In August 1915, 20,000 more Armenians from the kaza of Adapazar were set en route to Konya in several convoys.[9] On 13 to 15 August 1915, 8,000 Armenians from Bardizag/Bağçecik were deported, following those near Döngel and Ovacık, to Konya and Bozantı.[10] On 17 to 19 August 1915, nearly 9,000 Armenians of Bursa, were deported in three convoys to Syria via Konya and Bozantı, in animal wagons or on foot.[11]

In parallel, deportations of Armenians from Konya province were initiated on 11 August 1915: One thousand Armenians of the town of Karaman in the province of Konya were deported via the Ereğli-Tarse- Osmaniye-Katma-Aleppo route to Meskene in the Syrian Desert, in accordance with orders from the Mayor, Ahmedoğlu Rifat, seconded by Halvacızade Haci Bekir and Hadimlizade Enver.[12] In mid-August 1915, around 1,500 Armenians from the sancak of Burdur and around 4,500 from Niğde, Bor, and Nevşehir, all in the province of Konya, were deported to Rakka and Ras ul-Ayn, then Der el-Zor. 1,500 other Armenians, established at Aksaray, were executed at the end of August 1915 by Nazmi Bey, kaymakam of Niğde, and Lt.-Col. Abdül Fetah, the director of the office of deportations at Aksaray.[13] On 20 August 1915, the first convoy of deportees from Akşehir (province of Konya) was set en route to the Syrian Desert. Around 5,000 Armenians from the town are deported to the same destination in the following weeks.[14] The following day, 3,000 Armenians from the town of Konya were deported in a convoy to Syria under the order of Ferid Bey, a.k.a. Hamal Ferid, the Secretary-Responsible of the Committee of Union and Progress (C.U.P.) at Konya.[15]

In the end of December 1919, 10,000 Armenian escapees were found in the province of Konya.[16]

Persecution, imprisonment and deportations of Greek-Orthodox Christian in the province of Konya

“At an early date, daily increasing terrorism had become manifest in this Diocese [of Konya] (…) whose Goverment officials persecuted in divers manners the Christians [i.e. Greek Orthodox Christians], and excited the Moslem element against them.

The attorney -general of Ak-Shehir [Ak-Şehir], Ismail Hakki, openly accused the Greeks of having Philhellenic sentiments, and called upon the Moslems to expel the Christians from their homes. A truly fanatic official, the Hussein Bey, Vali of Konia, and his famous successor, Azmi Bey, officially proclaimed that the only means of saving Turkey from the danger that menaced her was to exterminate the non-Moslem element. The situation of this diocese became still more critical owing to the disarmament of the Christians, and the arming of the Moslem population.

Procope, Metropolitan of Konia, wrote under the date of the 2nd February, 1915:

‘It is no exaggeration to say that the sufferings of the Christians here surpass those of the Hebrews in Egypt, whom those in power had condemned to annihilation. The Greeks of the Diocese have been absolutely passed over in business; their goods have been systematically requisitioned; no end of difficulties created for them in the transport of other goods to replace them, imported articles as well as local products do not escape being requisitioned; taxes without end, and numerous subscriptions are imposed on the Christians. Hundreds of these unfortunate creatures are forced to hard labour in the open air, exposed in the winter season to privations and sufferings, and lacking the strictest necessaries for the maintenance of their families.

**As if this was not sufficient oppression for the Christians, the Authorities have inaugurated a new system of persecution started a few days ago.

‘A number of persons, bearing the vilest character, bring false accusations against peaceful and hard-working Christians, who are arrested and brought up before the Court Martial of Konia. There, without any previous examination, they are either condemned to imprisonment, fined, or given supplementary hard labour. This procedure resulted in the prisons of Konia, Sylle [Sille], Karaman, etc., being full of Christians. Until lately the province of Nigde [Niğde] has been spared, thanks to the good intentions of its Governor. Unfortunately the system of denunciation was introduced into this region also, a number of Christians became the victims of calumny at Nigde, Poro, Kuldjouk, Hassa-keuy [Hasaköy] and other places, and it is reported that still greater calamities will befall the Greeks in the near future, for the Vali of Konia, whose hatred against the Christians knows no bounds, accuses the latter openly of malevolence and treachery, and declares that it becomes imperative for the security of the State that this element be expelled from this territory, abandoning the fortunes they acquired by taking advantage, as the Vali pretended, of the simplicity of the Moslem element.

This is now the situation created for the Christians, which does away with the privileges they enjoyed hitherto, and making the position of our educational institutions intolerable. Our priests are dragged by force and without any reason before the authorities, with the object of intimidating the community. The inspectors of public instruction, transmit direct to the professor, and without the knowlegde of the Bishopric, orders as to the programme and mode of teaching to be followed as well as the things to be taught. My verbal and written protestations are taken no notices of, or mere promise? are given, and the professors whose diplomas have not been confirmed by the Ministry or some other institutions are threatened by dismissal. Latterly, NIDGE has served as a centre through which drilled troops coming from Constantinople are sent to Erzeroum, and recruits coming from Cesaria are sent to Constantinople, lender pre- text, therefore, of accommodating the soldiers, the military authorities have now requisitioned the schools of Nidge which have cost so much in money and trouble.’”[17]

In 1923 in the frame of the forcible population exchange between Greece and Turkey, the Greek inhabitants of the village of Sille (near the city of Konya), left as refugees and settled in Greece.