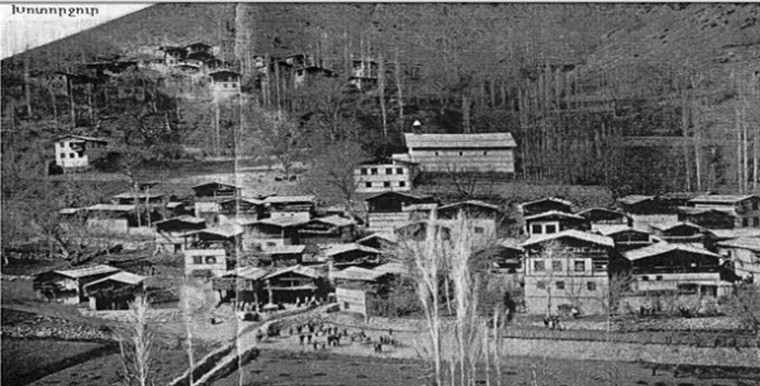

The administrative seat of the kaza, Khotorjur (Trk.: Sırakonak) is located at the foot of Kajkar mountain, on the left tributary (Mets River) of the Chorokh (Trk.: Çoruh) River in the Khotorjur basin. It was formerly known as Hodiçor, Xodiçur, Xodrçur and Xodorçur.

Toponym

The Armenian placename Khotorjur means ‘gras’ or ‘straw water’.

In 1912, the district and the city of Kiskim were named after the Ottoman prince Yusuf Izzettin.

Administration

Before the 1915 genocide the settlement of Khotorjur (Sırakonak today) was the centre of a group of thirteen villages populated mostly by Catholic Christian Armenians.

Khotorjur (also known as Khotojur, Khotayjur, Trk.: Hadiçorköyü, Hodiçor, Hodiçorköyü), was an autonomous community in the 16th-20th centuries. Situated in the district of Kiskim in the Erzurum Province, the Khotorjur community consisted of two village groups (nahiye) in the early 19th century: The first nahiye included nine villages: Chichapagh, Krman, Kisak, Mijintagh, Khandadzor, Sunints, Kaghmkhut, Vahna, and Geghut, the second the three villages Mokhruykut or Mokhurkut (Upper and Lower), Gorker, and Aregin. The village of Karmrik on the right bank of the Chorokh (Trk.: Çoruh) River also referred to Khotorjur.

Population

“The kaza of Kiskim, in which the 13 villages of Khodorchur were located, had an Armenian population of 8,136. Most of these Armenians were Catholics. Kiskim, a mountain district well suited for sheep breeding, was one of the most isolated areas in the vilayet of Erzurum. The villages of Khodorchur were rich and peacably inclinced.” [1] They maintained 14 churches and 5 schools.[2]

The Armenians of Khotorjur spoke a distinct dialect of Armenian. It belonged to the Western dialects of Armenian, but had features characteristic of the Eastern dialects as well as features unique to itself or shared only with the neighbouring Armenian dialect of Homshetsma. The Khotorjur dialect is now extinct, and no known vocal recordings of it survive. The forcibly Islamized Armenians in the villages around Khotorjur preserved their mother tongue or spoke ‘half-hearted’ (mixed Armenian-Turkish). Islamization was also a consequence of excessive tax increases in the mid-17th century.

The main branches of the economy were agriculture (grain processing), cattle breeding and handicrafts.

After the Armenians left territories, Hemşin people from Çamlıhemşin and Hemşin settled the district. They continue to keep alive their Black Sea cultures like tulum, which is a type of bagpipe (for more information about the relations between the Armenian Catholics of Khotorjur and Hemşin people cf. Kaza Hemşin).

History

Tayk

Tayk (Տայք – Taykʿ) was a historical province of the Kingdom of Armenia, one of its 15 ashkhars (‘worlds’; provinces).

There was a proto-Armenian confederation, Hayasa-Azzi, in this area in the 2nd millennium B.C. It was probably the same as (and with a name likely related etymologically to) the Diasuni and Diauehi of Assyrian and Urartian sources. From the 2nd century B.C. to the 9th century A.D. Tayk was a part of Armenian kingdoms or ‘autonomies’: Greater Armenia, Marzpan Armenia and Bagratid Armenia.

According to Strabo, the area around Tayk was originally Iberian, but during the time of Artashes (Artaxias) I it was conquered by Armenia.

In 999 A.D., Tayk or Tao became part of the Georgian Bagratid principality of Tayk’-Kharjk’ or Tao-Klarjeti. The Tayk province covered the contemporary Turkish districts of Yusufeli (Kiskim) in Artvin Province and Oltu, Olur (Tavusker), Tortum and Çamlıkaya (Hunut) to the north of İspir in Erzurum Province. To its southwest is found the ancient region of Sper. After World War I, Armenia and Georgia contested the region, with particular conflict over Oltik (Armenian: Ողթիկ – Voght’ik). As a result, in 1920, after the Russo-Turkish attacks Armenia lost the region of Oltik, which become a part of Turkey.

Khotorjur, the ‘Little Rome’

In the early Middle Ages (3-8th centuries) the area of Khotorjur was the family property of the Mamikonian (in the province of Tayk). Among the old historical monuments, the Fortress of the Mother of God (in Mokhurkut / Mokhrgud) and the Jrarajur Fortress on the right bank of the Chorokh have been preserved. In the 17th century the population of Khotorjur converted to Catholicism. For this reason, Khotorjur was colloquially called ‘Little Rome’.

Each village in Khotorjur had an elected village council, which exercised autonomy under the leadership of the elder. In the village of Chichapagh, the congregation had a special meeting place.

Khotorjur paid an annual tax to the Ottoman authorities; Ottoman officials did not interfere in the internal affairs of the community. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, all the villages of Khotorjur had schools, where from the beginning, in addition to Armenian, French, Turkish and Russian were taught. Some sent their children to boarding schools and colleges in Erzurum and Trebizond, as well as to the Murat-Raphaelian school in Venice.

In 1914, the Aghavni Tayots (‘Dove of Tayk’) newspaper was published in the village of Krman. The scarcity of land forced the men of Khotorjur to emigrate from a young age. In the 19th century emigration became widespread. Migrants and emigrants from Khotorjur went to Erzurum, Trebizond, the Caucasus, Crimea, Ukraine, Southern Russia, where they were mainly engaged in baking (bakers).

Khotorjur fought a fierce battle against Muslim gangs (especially in the 1870s). The Armenians of Khotorjur were deported in early June 1915, many of them were massacred along the way. After Russian forces captured Erzurum and the surrounding settlements in February 1916, the survivors from Khotorjur returned to their homeland, and began to rebuild their settlements. But at the end of 1917, after the second retreat of the Russian army, the Ottoman army attacked Khotorjur, and the self-defense of Khotorjur started.(3)

R. Tatoyan: Massacre of Armenians and Self-Defense – Khotorjur and Neighboring Settlements in 1915

By the order of the Turkish government, the deportation of Armenians from Khotorjur and neighboring villages to Mesopotamia was carried out in May-June of 1915. The population was divided into five groups for the deportation.

Groups from Khotorjur were subjected to massacres throughout the deportation process. The first group was almost completely killed at the beginning of the road near Gasapa [Kasaba] and Baberd [Bayburt]. Turkish and Kurdish rioters threw the corpses of their victims into the Chorokh River.

The second group was slaughtered and thrown into the gorge on the road between Gasapa and Yerznka [Erzincan]. The third group set off on June 8, 1915, in the direction of Gasap [Kasaba] – Baberd [Baburt] – Yerznka [Erzincan] – Kemah – Malatia (where men were slaughtered) – Urfa – Aleppo.

The men of the fourth group were killed in the mountains on a route to Malatia. This was followed by the massacre of women, elderly, and children on the banks of the Euphrates River near the settlement of Samsat. Regular troops of the Turkish army took part in the massacre.

Manik Babasyan, a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, described the massacre of women and children of Khotorjur on the banks of the Euphrates as follows:

“The river became a grave for many. But the terrible was ahead. During the crossing of the Euphrates River, ferocious policemen threw the sick into the water, claiming that the ship allegedly could not take all of them.

In addition, many healthy survivors and children were hacked with swords and beat up to death with sticks. The caravan from Karin [Erzurum] and Khotorjur consisting of 30-35 thousand Armenians was destroyed. Only about 50 people were able to survive, hiding under the corpses…”

The fifth group was slaughtered in Diyarbekir near the village of Poshin of the province [district] of Severek. On the path leading to inevitable death, women from Khotorjur did not give up their faith. Survivor Verzhine Zarifyan testified:

“When the Turks and Kurds offered women to leave with them in order to save their lives, ignoring and despising Turks and Kurds, they said: ‘We would rather die for our people and sacred faith than go with a Turk or a Kurd’.”

The pastor of Khotorjur, Nazlyan, wrote in his memoirs: “Devout Catholics from Khotorjur together with their priests were examples of the righteousness of a long and painful way.

Every day, they came to receive holy communion until they lost their mass as a result of the painful death of many believers. And women, in spite of all kinds of cruel tortures to which they were subjected and thanks to their persistence and patience, simply remained heroines.

When they reached Kemakh-Pokhaz [Boğaz], they faced a choice: throw themselves into the abyss or change their faith. After crossing themselves, the group threw themselves down into the abyss.”

An excerpt from the report on the Khotorjur massacre:

“The population of Khotorjur has remained faithful to its faith and the national ideal…

On their way, they remained themselves without breaking their vow, denying their faith, and insulting the values of their ancestors. All the people passed away voluntarily, initially knowing that they were sacrificing themselves for their beliefs.

From the roots of Chorokh River to the deserts of Syria and Arabia, the smallest groups that managed to survive the previous weeks of the death march showed the greatest feats of courage and dedication.

A man or a woman, an adult or a child, a priest or a layman – all with enthusiastic zeal preferred death to life, melancholy to rowdiness, exile to slavery… Neither threats, nor hunger, nor temptation, nor treachery could defeat the will of the women from Khotorjur.

They were slaughtered, tortured, thrown into the water, but in exile, they preferred poverty, hunger, hard labor, rags, but they were in no way inferior to the executioners and deceivers.”

Of the thousands of inhabitants of Khotorjur who were exiled to Mesopotamia, about a hundred people survived the Great Massacre [Armenian: Mets Yeghern].

The Self Defense of Khotorjur

Before the war, the “Taik” alliance consisting of the residents of Khotorjur (there were about 1.500 in the alliance, mostly men), set off to the Caucasus and Russia to earn money. Thanks to this, they avoided the massacre.

In the spring of 1916, the “Taik” alliance organized and sent detachments of young men to Khotorjur to protect the country and prepare food supplies. They hoped that at least some of the deported residents of Khotorjur would return to their homes.

In early 1918, after the Russian troops retreated from Western Armenia, Turkish troops, violating the truce concluded in Yerznka [Erzincan] on December 5 [1917], proceeded on to occupying Armenian provinces. The inhabitants of Khotorjur – 110 people – decided to resist and began to prepare their self-defense. A Military Council headed by Ogostinos Mchanyan was organized.

On January 20, 1918, the Turkish army undertook their first attack that would last four days. Particularly stormy battles took place in Klahints in Handadzor where the Turkish army would be eventually defeated. Subsequently, the center of the resistance moved to the village of Verin Mokorkut [Mokhruykut or Mokhurkut] that had naturally strong defensive positions.

Having resumed their offensive, the Turkish army utilized artillery, which complicated the ammunition issue of the besieged Armenians. Nevertheless, they managed to destroy the artillery.

Khotorjur resisted heroically and selflessly, but its forces and ammunition eventually ran out. The people of Khotorjur sent a messenger to Andranik Ozanian asking for help but were rejected. Andranik replied: “To free a hundred people, we have to sacrifice a thousand.”

The self-defense of Khotorjur against the superior Turkish forces continued until May 1918. Learning that the Turkish troops had captured Kars and that there was no hope for help, the Military Council decided to retreat in small groups.

The first group with great difficulty managed to reach Ardwin [Artvin] and then the Caucasus. The second group was captured by the Turks and imprisoned in Trabzon. After the defeat of Turkey [Armistice of Mudros, 30 October 1918], they were released.

The descendants of the survivors of the Khotorjur self-defense now live in Armenia, Tbilisi, and Abkhazia. Some families live in Iran, Italy, and the United States.[4]

Destruction

When the general mobilization of the Ottoman Empire was announced, the villagers of Khotorjur chose to pay the exemption tax (bedel) “for both themselves and the emigrants from the area working abroad, rather than serve in the Ottoman Army. From late August 1914 on, they also lodged and fed several battalions of the Ottoman Army – protesting mildly, and to no avail, when the army requisitioned all their horses and mules. In December 1914 the little town of Garmirk was also visited by some 30 çetes, who plundered and beat the villagers and imposed a tax of 300 Turkish pounds on them. (…) The house searches conducted in February 1915 by gendarmes looking for arms had been more alarming, especially because they were accompanied by acts of torture and the arrest of village notables, as in Mokhragud (Harutiun Dzarigian / Tsarikian) and Khodorchur (Joseph Mamulian).

Because the majority of Armenians in Khodorchur were Catholics, they had until then benefited from the protection of French and Austrian-Hungarian diplomats. Hence they were probably hoping when they received the deportation order that the ambassador of Austria-Hungary would see to it that they were not harmed. Interestingly, negotiations conducted by the German vice-consul [Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter] in Erzerum at the American ambassador’s request, though dragging on from June to September 1915, succeeded in saving only about a dozen Armenian Sisters of the Immaculate Conception and a few Mkhitarist monks; the Catholics of Khodorchur as a whole were not spared. Quite the contrary: in May 1915, the local authorities proceeded to arrest 27 priests who had been educated in Rome or at the seminary of Saint-Sulpice in Paris – among them the primate, Harutiun Turshian, as well as some 30 schoolteachers. Late in May, the kaymakam, Necate Bey, summoned the notables of Khodorchur and informed them of the deportation order, adding that they would not be allowed to sell their assets before setting out.”[5]

The first convoy of deportees from the kaza Kiskim started in early June 1915, comprising 300 families of the villages of Khotorjur (around 3,740 people), and the second convoy of 200 families (around 1,500 individuals) mostly from Kudraşen and Kiskim, were dispatched and entirely liquidated between Kasaba and Erzincan by Special Organization squadrons.

On 8 June 1915, the third convoy, made up of inhabitants of the villages of Garmirk (600 souls) and Hidgants, was dispatched and rejoined the second caravan of Erzurum, and the two suffered the same fate. After having passed through Bayburt, Erzincan, Kemah, Eğin, Malatya, Arapgir, Samsat, Suruc, Raffa, Birecik, and Urfa, only twenty survivors were counted at Aleppo on 22 December 1918. The fourth convoy, made up of villagers from Mokhrgud (350 people), Kotkan, Atik, Grman, Sunik, Gakhmukhud, Keğud, Cicaroz/Cicabağ, Gisag, Mitchin Tağ, and Khantadzor, followed a route similar to that of the third caravan as far as Samsat, but were then decimated on the banks of the Euphrates between Gantata and Gavanlug by regular troops and bandits commanded by Samsatlı Haci Şeyh İçko .

On 18 June 1915, the second convoy of deportees from Erzurum was set off in the direction of Bayburt. This convoy was made up of 1,300 middle-class families, who were joined en route by 370 families of the town of Garmirk (kaza of Kiskim), for a total of approximately 10,000 people. They were escorted by gendarmes commanded by captains Muçtağ and Nuri and supervised by two leaders of the Special Organization, the kaymakam of Kemah and Kozukçioğlu Münir.[6]

Dual Victimization: The Story of The Gevorgyan Family From Khotorjur

“The Gevorgyan family was one of the prominent families living in the Khotorjur village group in the Kiskim district of Erzurum province.

On the eve of the Armenian Genocide there were 978 Armenian houses in 9 quarters of Khotorjur, with a population of 6,906 mostly Catholic Armenians. The Gevorgyans’ grandfather, Serob (born in 1824, in Mijintagh, a village in the Khotorjur group), married Almas Kuroghlyan from Khotorjur and they had six children: two daughters, Maruz and Saner and four sons, Harutyun (1860-?), Galust (1865-1926), Hovhannes (1870-1934) and Ispiridon (1874-1939).

Galust Gevorgyan, marrying Vergine, the daughter of brother of the famous Ter Karapet Chakhalyan from Mijintagh, had six sons: Serob (1891-1948), Artashes (1894-1937), Torgom (1898-1982), Yervand (1903-1986), Manas (1903-1964) and Alexan.

The Armenian Genocide wave reached Khotorjur in May-June 1915. Of the thousands of people from Khotorjur who were driven to the deserts of Mesopotamia, only about a hundred survived. A few other people from Khotorjur also survived as they were working abroad. Among them were some members of the Gevorgyan family, who were famous bakers working in Tbilisi at that time.

Some members of the Gevorgyan family, including Maruz, Saner, Artashes’ maternal grandmother Nanoz and five of uncle Ispiridon’s six children were killed during the deportation on the road from Khotorjur to Hunur.

People from Khotorjur who survived the genocide returned to their homes in 1916 with the advance of the Russian army. With the Russian army’s retreat following the Russian revolution in October 1917 however, the people of Khotorjur were forced to emigrate for the second time.

Artashes Gevorgyan later moved to Tbilisi with his parents in July 1922. Jemal Pasha, one of the main organizers of the Armenian Genocide, also arrived in the city at about the same time. He was assassinated there by Artashes Gevorgyan and his friends Petros Ter-Poghosyan and Stepan Tsaghikyan on July 21, 1922, at about 22:00 hours.

Some of the Gevorgyans, including Hakob, Artashes, Serob and Torgom, who had migrated to Tbilisi, were repatriated to Soviet Armenia in 1924.

Artashes Gevorgyan managed, in 1925, to get the consent of the government of Soviet Armenia to establish a village called Nor Khotorjur in the motherland for the people of Khotorjur living in the Donbas. It was created in a half-ruined place called Gorukh-Gyune, on a 720 hectares area near Nerkin Akhta (currently in the Kotayk region, near the village of Hankavan in the Republic of Armenia).

The Khotorjur community formed the first collective farm in Armenia. Deportees from Khotorjur, settled there from different places, elected Artashes Gevorgyan as the chairman of the community during their first meeting.

Axel Bakunts, the famous prose writer, literary critic, screenwriter, translator and agriculturist, who was a devoted friend of the community, spent many days there giving them encouragement. One of Bakunts’ works, ‘The Community of Khotorjur’ was dedicated to this community.

Artashes Gevorgyan, however, like many others, fell victim to Stalinist repression in 1936. He was arrested and was shot on the night of August 14, 1937. He was posthumously rehabilitated in 1956. The book ‘The Assassination of Jemal Pasha’ was written by Artashes’ brother Torgom Gevorgyan (Azvin).

Yervand Gevorgyan wrote the story of his family at a mature age, in the 1970s. This narrative was handed over to the Armenian Genocide Museum-Institute by his granddaughter Vergine Gevorgyan. (…)

The descendants of the Gevorgyans family currently live in the Republic of Armenia, in the Russian Federation and in the United States.”

Source: www.genocide-museum.am; https://allinnet.info/history/the-story-of-the-gevorgyan-family-from-khotorjur/