Toponym

Nusaybin (Akkadian: Naṣibina; Classical Greek: Νίσιβις – Nisibis; Arabic: نصيبين, Kurdish: Nisêbîn; Syriac: ܢܨܝܒܝܢ – Nṣībīn, Armenian: Մծբին – Mtsbin. The name of the city was Nisibis in ancient times.

History

The city of Nisibis (the later Nisibin) is documented since the 10th century B.C. In 901 B.C. the Assyrian king Adad-nirari II went to war against the Temanite Nūr-Adad of Nisibis. From the middle of the 9th century B.C. to 612 B.C. it is documented as an Assyrian provincial capital.

Under the Seleucids, Nisibis bore the name Antioch in Mygdonia, but this name fell into disuse when the city first became part of the kingdom of Adiabene under Parthian rule from 141 B.C. onwards, then became part of Armenia. From about 36/38 AD onwards, Nisibis belonged to the Parthian Empire.

The city came under Roman rule in the Parthian War of Septimius Severus at the end of the 2nd century A.D. and was fiercely contested between Rome and the Sassanid Empire in late antiquity due to its favorable location and its economic and military importance. The city changed hands repeatedly. In 298, in the first Peace of Nisibis, important parts of northern Mesopotamia became Roman, including Nisibis, and the city was designated as one of three locations where trade between the two great powers was to be conducted.

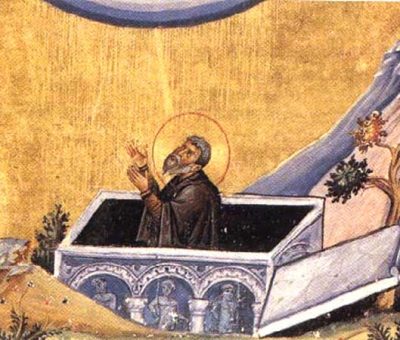

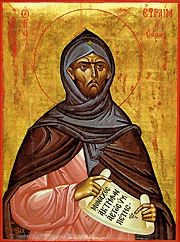

From 309 to 338, Jacob of Nisibis was bishop of the Christians of Nisibis. He had the church built, which was later named after him and in whose ruins his tomb is located. The Persian King Shapur II besieged the city three times in the fourth century in vain (338, 346 and 350), but after the failed Persian campaign of the Emperor Julian, his successor Jovian had to leave Nisibis to the Sassanids in the Persian-Roman Peace treaty of 363. Most of the Roman inhabitants had to leave the city, among them the ecclesiastical teacher Ephrem the Syrian, and were replaced by Persian families who settled in Nisibis; this disgrace remained unforgotten in Rome for a very long time. Even more than 120 years later, the Eastern Romans were to demand the return of the town, and in the 6th century, imperial troops tried in vain to conquer Nisibis at least twice (543 and 572).

The place was very close to the Roman territory, was one of the strongest, largest and most important Persian fortresses and housed a garrison of several thousand men. In the 6th century, in order to face the threat that emanated from Nisibis, the Eastern Romans expanded the town of Dara (Grk.: Daras)-Anastasiupolis, located not far from the city on the other side of the border, into a counter-fortress and also stationed strong troops there. With the peace treaty of 591, Nisibis came back under Roman control and was again heavily fought over at the time of Khosrov II.

Nisibis was already the seat of a metropolitan in the early 5th century; this became Nestorian a little later. Nestorian Christians and other religious minorities persecuted in the Imperium Romanum settled in Nisibis in large numbers. The city was thus also a highly important religious and – since the famous school moved from Edessa to Nisibis in 489 – academic center. It was probably conquered by the Arabs in 639/640 in the course of the Islamic expansion and was subsequently, apart from a few brief episodes, controlled by Muslims.

Probably Nisibis was one of the places where the knowledge of Greek-Roman antiquity was passed on particularly intensively to the Arab conquerors. Since a severe earthquake in 717, the city, which had already suffered from the loss of border trade between Romans and Persians, lost much of its importance. From 1515 the Ottomans ruled the city.

Population

About one third of the population of 8,000 of the town of Nisibin was Christian, mostly Armenian Catholics and Syriac Orthodox. According to Süleyman Hinno (Henno), there were 100 Syriac Orthodox families in the town of Nisibin.[1] The census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople gave the number of Armenians in the kaza on the eve of World War I with just 90 in one locality (the town of Nisibin), maintaining one church.[2] Among the other inhabitants were Kurds and some 600 Jews.[3]

David Gaunt: „A famous ancient town”

„Nisibin was a famous ancient town that is on the plain just to the

south of the slope up to Tur Abdin, and the river Harmas flows through it. Today it is on the border between Turkey and Syria. By World War I it was a small, rather forgotten place, but when the Baghdad railway made it a station in 1916, it had strategic importance. (…)

The town and its uplands are among the oldest Christian settlements in Mesopotamia, dating from the second century. Lying at the foot of a steep incline, the town of Nisibin was a caravan stop on the flattest and most abundantly watered trade route between Persia and the Mediterranean Sea. The river Jaq-jaq runs through it. In antiquity it was a fortress town that was once Roman and then, after 363, became Persian; the frontier went through the neighborhood until Muslim conquest. The pilgrimage church of Mar Ya’qub dates from the fourth century.

From about 300 A.D. it had been a bishopric in a diocese named Beth-‘Arbaye. After the Council of Ephesus in 431, Nisibin developed into a center for Nestorian Christianity, and it had a famous school of divinity. After the Ottoman conquest in 1515, it served for a period as provincial capital. (…)

During late Ottoman times, Nisibin was a garrison town for troops employed in stamping out Kurdish rebellions. By the start of the World War, Nisibin was planned to be a station on the railway to Baghdad. Here was the seat of the kaymakam. Many survivors of the 1915 massacres found work here finishing the railway line, cutting timber in the forested mountain slopes (the only wooded tract in the region), burning charcoal for the trains, and so on.”

Excerpted from: Gaunt, David: Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006, p. 241f.

Destruction

November 1895

“On November 10, 1895, one of the Hamidiye pogroms occurred here, but the Tayy Bedouin tribe protected the Christians then, as they continued to do in World War I.

The Syriac archbishop in Homs, Efrem Barsom, named 50 villages in Nisibin’s upland that were ruined. The affected Syriac Orthodox population was approximately 7,000, coming from about 1,000 families. The Syriac Orthodox farming population had recently migrated from Tur Abdin. Many of the villages in this district were on level ground and lacked the ability to defend themselves against outsiders. Therefore, those who could went to villages higher up in the nearby Izlo Mountain, which formed a steep slope up to the Tur Abdin plateau. Among those who fled from the town were about 30 youths.”[4]

June – August 1915

“At the start of the troubles, a committee was formed to organize the atrocities in the Nisibin region. It was headed by Refik Nizamettin Qaddur Bey and Süleyman Majar. Qaddur Bey held the rank of lieutenant and commanded the local Al-Khamsin militia units. According to Armalto [Ishaq Armale(t)], the committee sent letters to the rural Kurdish chiefs ordering them to get rid of their Christian tenants. Among the Kurdish leaders who obeyed this summons were Ibrahim, the Agha of Khezna, Ahmed Yousuf, Muhammed Abbas Agha of Dawkar, and Ali Isa. Gangs of ‘çete’ were organized by Qaddur Bey to crush the rural villages. At first, the local authorities and Kurdish tribal chiefs assured the Syriac Orthodox population that the massacres and deportations that affected the Armenians would not be done to them. Some Syriacs did not believe these promises and fled to the mountains. Many Christian villages were completely annihilated.

The first notable to be killed was Gorgi (Gewargi) Abrat, who was arrested on June 4 and sent to Mardin, where he was included among the several hundred who were executed on June 10. There is some confusion as to the chronology of events in Nisibin, as orders and counterorders were given to local authorities. On June 13, all of the Armenian and Syriac adult men, including some from the neighboring villages, were arrested and put in jail. All of them believed they would be executed, as they already knew about the recent death march at Mardin. They were accused of belonging to secret Armenian revolutionary societies. On the morning of June 14, the authorities released all of the imprisoned Syriac Orthodox men and told them to go home and be calm. The same afternoon, all of the other Christians were freed. A few immediately fled to Sinjar Mountain, which was only a few days’ journey south. However, on June 15, the just-released Armenian, Syriac Protestant, and Chaldean men were again imprisoned, and that night they were executed. They were assembled, marched out of town, and slain at a stone quarry. At the same time as these events were going on, the Syriac Orthodox priest Istayfanos was summoned to the town hall. An official pretended to send the priest to the countryside to deliver the important message that it was now safe for the Syriacs to come out of hiding and return to town. Soldiers escorted Istayfanos, but once outside the town, they tortured and murdered him. The next day, all the Syriacs – men, women, and children – that the militia could find were assembled at the town hall and told that they would be marched to Mardin. When they came to a place called Nirbo d Afrasto, they were surrounded by the militia and slaughtered. The bodies were thrown into a well. On June 28, some remaining Armenian women in Nisibin were arrested, brought to the stone quarry, and slaughtered.

As a consequence of the government policy of divide and conquer, at first some of the large population of Jacobite [Syriac Orthodox] Christians had been spared, while the other Christians were exterminated. But on August 16, the Syriac Orthodox notables, including the bishop, were slain at a place outside the town. [The Catholic priest] Hyacinthe Simon records that it was a ‘massacre of all Christianity’, ‘more than 800 persons’. The important clan of Shouha was transferred to Mardin to be tried by a judge. According to one account, all of the Christians of Nisibin had been killed except the handful who escaped to Mount Sinjar.”

Excerpted from: Gaunt, David: Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2006, pp. 242-244

“In June 1915, the round-up of Christians from Nusaybin (about 400 families) and the surrounding villages began. After a brief release by a Turkish officer, they were imprisoned again and then murdered in a quarry near the town. First the Armenians, Catholics and Protestants were killed, then a little later the Arameans [Syriac Orthodox] were murdered. About 30 young Arameans managed to escape to the mountains and save themselves from the massacre. Some Christians from the surrounding villages were protected by the leader of the Tai clan, Mohammed, and his friend Hammo Sharo, and saved from being killed.

The monk and priest Stephen (Estiphanos) became a martyr. Accompanied by soldiers, he was supposed to deliver the message to the local Arameans that they were safe and protected by the government. However, during this action he was tortured by the soldiers, his hands and feet were cut off and finally he was beheaded.

Then Qaddur, the commander-in-chief, gathered all the women and children and locked them up in the church of Mor Yakub. Then he led the women to a place named Kharabe Kurt and murdered them after sorting out the pretty girls. He tied the children with ropes, led them to the field outside the village and let the horses trample them with their hooves.”

Excerpted and translated into English from: http://www.jahrestag.stiftung-aramaeisches-kulturerbe.de/nusaybin.html

The ancient town of Dara-Anastasioupolis (Grk.:Δαραί; ’Aναστασιούπολις; today the village Oğuz), in the northern part of the kaza Nisibin, was the scene of repeated slaughters; “this suggests that the ruins of the ancient city had been chosen as a killing field. In addition (…) let us mention, for example, the 11 July 1915 massacre of 7,000 [Armenian] deportees from Erzurum in Dara, whose bodies were thrown into the town’s immense Byzantine cisterns.”[5]

The massacres in Nisibin in the summer of 1915, which were directed against the entire Christian population, became the epitome of genocidal extermination for Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholic Christians. In 2015, the Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholic Churches recognized the 15th of June (1915) – the day of martyrdom of the monk priest Istayfanos and his community of about one hundred people – as a day of commemoration of the extermination of Aramean Christians. The monk priest was dismembered near the city of Nisibin (Nusaybin), which is a place of theological education, science and culture for all the Syriac Christians, in order to force him to accept Islam. The months of June to August 1915 marked the climax of the extermination of the Aramaic Christians in the Tur Abdin region (southeastern Turkey) and the cities of Mardin and Diyarbekir.

Kuru village, 2006/2007: Mass Grave Discovered in Cave and ‘Polluted’

As Turkish human rights defender Ayşe Günaysu reported in the Kurdish newspaper Ülkede Özgür Gündem on 30 October 2006, farmers from the village of Xirebebada (Harebe Baba, now Kuru) accidentally came across skulls and bones in a cave. When they reported their horrific find to the authorities, they were instructed to seal the cave entrance and maintain silence. The remains were believed to be those of massacred Armenians and Arameans/Chaldeans.

However, the chairman of the Turkish Historical Society and supreme guardian of official historical doctrine, Dr. Yusuf Halacoğlu, soon intervened with the claim that these were far older bones from the Roman period. Prof. David Gaunt of Sweden’s Södertörns University College then proposed a joint investigation of the site. For such investigations, there exist internationally proven criminological rules, the most important of which is that only an untouched, i.e. neither intentionally manipulated nor unintentionally “polluted”, site or crime scene can be meaningfully investigated. When D. Gaunt had to realize on 23 April 2007 that obviously the cave at Kuru had been prepared according to the Halacoğlu’s Roman thesis, he had the international investigation aborted.

David Gaunt: Press release – Mardin Mass Graves Revisited

12 February 2006

“In the autumn of 2006 villagers in Kuru (previously known as Harabe Baba) between Mardin and Nusaybin discovered a mass grave in a cave. They identified the victims as “Armenians from 1915” and added that they had found similar mass graves previously. A few photographs were taken and Ülkede Özgür Gündem wrote an article as did the journal Nokta. Both interviewed me on my opinion as I had written a book about massacres in this region. I suggested that the mass grave might be that of the victims of one of several massacres documented by contemporaries. There was documentation of killings of people taken from nearby Dara, Nusaybin, and Mardin as well as of the last remnants of a deportation column that had started in Erzurum. The sparsely settled area where the mass grave had been discovered is on the line of ancient defence works and underground storage rooms dating back to Roman times. It was turned into a killing field during the summer of 1915. With great probability the cave should contain Armenian, but with some likelihood also Assyrian-Syriac and Chaldean victims. But only a site investigation could tell.

After the first news was spread, authorities cordoned off the cave and only some government agencies had access. Finally in December the site was closed off and the opening was buried. The head of the Turkish Historical Society (TKK), Professor Yusuf Halaçoglu challenged my suggestions and insisted that the bodies found were from Roman times. Thereafter he made many statements to the press challenging a Swedish delegation to investigate the site. This intensified after a debate in the Swedish parliament on December 12, 2006, which was based on reports in Turkish press (not upon my initiative, as some mistakenly believe).

In mid January 2007, I sent up a trial balloon to see if there was any substance to the TKK statements and I proposed to start negotiations on making a joint investigation. It was apparent that the only way any independent scientist would have to study the grave was through some sort of collaboration with the TKK. I am fully acquainted with its abysmal track record on the Armenian-Turkish issues and was, and still am, very hesitant. We had not progressed further than discussing the possible dates for an initial planning meeting, when Hrant Dink was assassinated. I immediately put these negotiations on ice. Apparently, however, the TTK is very hot to pursue this matter and today has gone to Hürriyet revealing the very small amount of progress we had up until the assassination and making some further provocative and totally inappropriate statements.

This investigation of the mass grave must be seriously planned. If the TTK wants to rush in and do an incomplete job in a hurry, there will be no reason for me to continue negotiations. For the sake of legitimacy alone, the TTK cannot expect to do the investigation all by itself and use the independent researchers only for PR-purposes in attempts to influence public opinion. Today I sent the following letter to Dr. Halaçoglu and proposed again a date for a meeting in Mardin. I envision a long scientific investigation with international co-operation. This first meeting can only begin the process of identifying the long lost victims in that mass grave.

Letter to Yusuf Halacoğlu

Türk Tarih Kurumu

Ankara, Turkey

Dear Prof. Halacoğlu,

Many thanks for your letter of January 17 to which I have not until now had opportunity to answer. I am sure that you realize that the assassination of Hrant Dink on January 19 made the situation for discussions about the mass grave difficult and most of our colleagues, including myself suddenly had many other things on our minds.

I was somewhat surprised to see from today’s Hürriyet and even from the TTK homepage last Friday, that you have begun to give information to the press even though we had only just started the preliminaries in what must be a long scientific investigation. I suggested a date for a meeting in Mardin to take the first steps and to make the first look at the mass grave. Unfortunately, these dates did not fit into your schedule, and you suggested some alternative dates. These proved impossible for me because of my teaching burden and prior engagements. May I propose a meeting in Mardin on 23-25 April?

What we still need to discuss are very heavy and difficult issues such as the budget, the size, qualifications and composition of the investigation team, the co-operation of local universities for offices and for adequate storage of the remains during the investigation, the organization for the search for DNA among people whose ancestors might be in the grave. Perhaps I overstate my position, but for clarity it will be impossible for us to call this a joint effort, and it risks the legitimacy of the whole enterprise, if the TTK takes on all responsibility for the investigative work and the independent researchers are kept at arms length, until there is a press conference.

To my pleasure, I see that we are agreed that there should be complete media transparency. While I am on the subject of transparency, please correct me if I am wrong, but I have reason to believe that there have been several Turkish government delegations that have already inspected the grave. You made statements yourself, so I assume the TTK participated. It would be very useful for our common planning if you could send over copies of whatever material there is in whatever form, which has already been assembled. I would take this as a sign of good collegial relations between professional historians who are about to begin a joint venture and, of course, it would greatly speed up the process of negotiations.

The Hürriyet article does contain a misunderstanding. I did not take any initiative to the Swedish parliament discussion of the mass grave. But some of the parliamentarians did read articles in the Turkish press in which I was interviewed and they used that information. I am sure you know that only a member of parliament can introduce a debate.

I see from the Hürriyet article that you have publicly offered to apologize to me in case your conviction about the mass grave is proved wrong. Please, you do not need to do this for me and I don’t understand the necessity of your odd promise, which seems more suited for film-version samurai warriors than down-to-earth researchers. In scientific circles we are daily confronted with new interpretations, new facts, new materials, new techniques and unexpected results – and as scientists we learn from them and are not embarrassed by new knowledge. As fellow historians, I believe that our first priority must be to pay our respect to the past and honor the memory by identifying whoever is enclosed in these long lost graves whatever ethnicity they happen to have had.

Stockholm 2007-02-12

David Gaunt, Professor of History

Södertörns University College

SE-14189 Huddinge

SWEDEN

Letter to Turkish-Armenian Weblist, 26 April 2007

Dear All

As you know by now I was at the mass-grave sıte on Aprıl 23 wıth Yusuf Halacoglu the presıdent of the Turkish Historical Society. For me thıs was a pilot case for the degree to which it was possible to do an international co-operation on a strictly scientific no-nonsense basis.

We were to make a preliminary survey of the grave in Kuru village, Nusaybin district, Mardin province, in order to see if a later scientific investigation could be made by archaeologists, forensic medical experts, physical anthropologists, historians and others. My role was simply to determine if this was a suitable site for a full-scale interdisciplinary research. The first task was to determine if the findings were intact according to the photographs published in October and November 2006 – which I had with me. I had asked also for the archaeological report from the Mardin museum that was dated December 1, 2006 but was not given because it would cause “complications”. I did get this report on the day after the visit to the grave.

Based on newspaper articles I expected to see the remains of 38 persons lying more or less on a pile on top of the floor of a cave with masses of skulls, fragments of skulls, leg bones and so on. The skulls were not blackened. Analysis of the photos had been done by forensic medical experts and they said it ındicated that someone had been arrangıng the skulls for the photos, so we already expected a certain degree of contamination to the site.

But I was thouroughly unprepared to discover that there were no skulls, skull fragments or large leg bones lying visible. To one side there were some very blackened rib-bones and few large pieces of Roman perıod pottery. When I protested, showed the photos, the Turkish side argued that it had been raining hard durıng the winter and maybe all of the bones had been covered in mud and that we could begın digging to find them. This in itself was an admission that the site was heavily contaminated since it meant that the opening had been left uncovered and unprotected. But why should the Roman pottery be lying neatly and cleanly exposed while all of the major bones had sunk into the mud. (I had previously heard from many sources living ın many countries that the bones had been removed at an early stage – obviously before the Mardin museum report of December 1. But I had belıeved that they would have been transported back for the sake of our scıentıfıc ınvestıgatıon.) I refused outright to do anythıng more in the grave site and left while professor Halacoglu made a statement ın the pouring rain for the medium size press group that was assembled there.

This was a very diısappointing result of an attempt to do some serious scientific work. The Physicians for Human Rıghts had agreed to do the forensic medical investigation and the Instıtute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation was to assist in the historical documentation. My task was to give a green light for a later full scale investigation with all necessary permits. I had to report back that this site was too contaminated, but there might of course be some evidence remaining for a painstaking undertaking.

I have not broken off dialogue wıth the Turkish Historical Society because of the grave fiasco as there are other seriously scientific things that we found worthwhile discussing. Only time will tell if this initiative is more fruitful.

Sincerely yours

David Gaunt