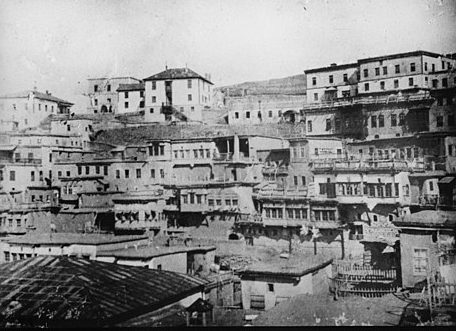

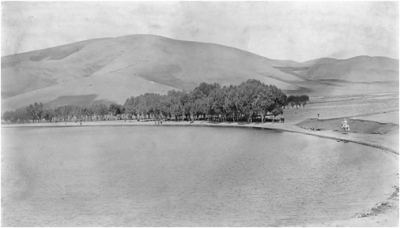

Surrounded by the mountain range of the Anti-Taurus, the Harput Plain is irrigated by the waters of the Euphrates and its tributary Aradzan (Trk.: Murat; Eastern Euhprates). At an altitude of 1,267 meters, the Harput Plain joins the Palu Plain to the east and the Malatya Plain to the west.

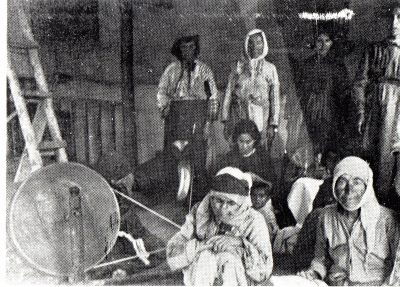

The city of Harput was surrounded by 365 villages and settlements, which were fed by the three fertile ‘golden’ valleys of the vast plain of Harput. Wheat, corn, cotton, a variety of vegetables and foodstuffs were produced. The hillsides were covered with orchards, walnut trees, and fruit trees. The region was famous for its wine, honey and mulberry trees. Thanks to the latter, the inhabitants were engaged in silviculture, silk production and export, and the production of natural dyes. And because of the many flocks of sheep, game-making and leather-making were developed.

Administration

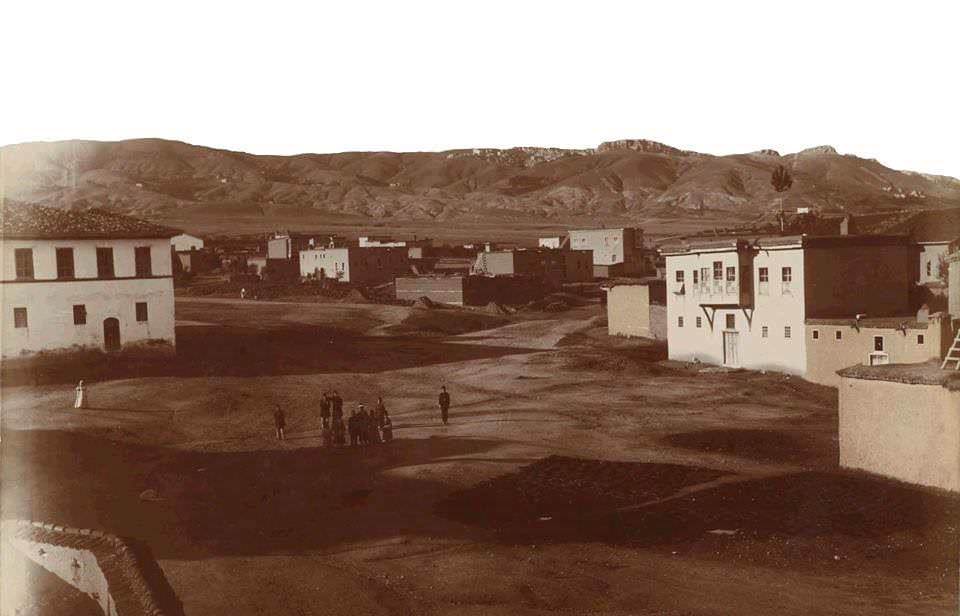

Mezre (also: Mezereh) is today’s Elazıg, which in Ottoman times formed the lower town of the double-provincial capital Harput-Mezre of the Mutesarriflik Mamuret-ül-Aziz (later Vilayet Harput). The much older Harput, an Armenian foundation (Kharberd) in the north-east of Elazıg, now forms an insignificant settlement.

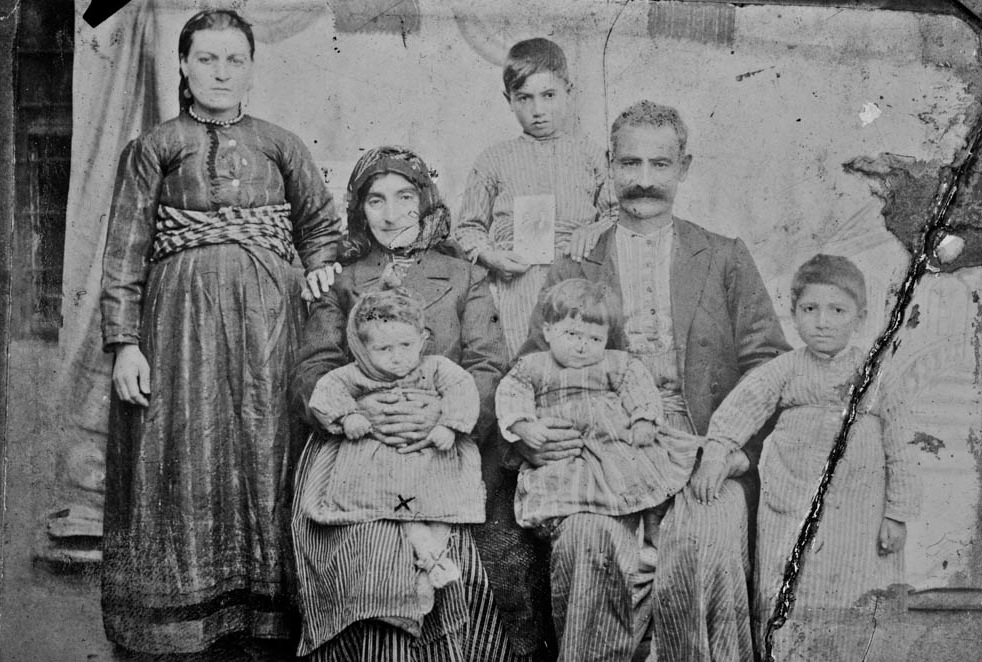

Armenian Population

According to the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, on the eve of the First World War there lived 39,788 Armenians in 57 localities of the kaza of Harput-Mezre, maintaining 67 churches, 9 monasteries, and 92 schools, attended by 8,660 children.[1] Most of the Armenians of the kaza lived in the plain of Harput: 20,590 peasants in 50 villages.[2]

78 Armenian Settlements in the kaza Harput

Harput (Kharberd; administrative seat), Alamilik (Elemlik), Akhor, Aghmezre, Aghndzi (Aghndzik, Aghnsi), Ayvos (Ayvaz), Ayubaghi, Andak (Endak), Ashvan, Arzruk (Erzruk), Arozik (Arosik), Arpavet (Alapaut), Bazmashen (Pizmishen), Barbach (Perchench), Boyraz (Poyraz), Gayli (Kayli), Garnkert, Geghavank, Gomk (Kunk), Gurbet Mezre, Datem, Yeghegi, Yenije, Erdmnik, Zardarij (Zardarich), Enkuzik (Enkezik), Tlantsik (Til-Andzit), Ibiz, Izolu (Izoglu), Ichme Lower (Small, New), Ichme Verin (Big, New), Khokh Verin, Khokh Lower, Khraj (Khrach), Khrkhik, Khulagyugh (Khulvenk), Khulyu (Kuyulu, Tlkatin), Tsaruk, Tsovk (Gölcük), Karmri, Kanepik (Kanfik), Konkalmaz, Habusi (Hapusi), Hakobigyugh (Yaghub Mezre), Havuk (Harik), Harsek (Harsik, Hersenk), Harsenk Mezre, Hatseli (Haci Seli), Huseynik (Hyusnyak), Hnagrak (Nagrak), Hndzor, Hoghe (Hoghi), Hoghe Mezre, Meghire, Mollagyugh (Mollakendi), Morenik, Munzur oghli (Muzur oghli), Muri, Shamushi (Shemsi), Shekhhaji (Shkhaji), Storin, Shentil (Shntil), Shushnas, Choteli, Chorgyugh (Chorchik), Djip’, Sarni, Saray, Sarbtsik (Sarpeli), Sarighamish, Sinan, Sursi (Sorsre), Vardatil (Vardetil), Vardenik, Verin Mezre, Pelte (Berdak), Kesirek (Gazrik), Korpe (Kyorpe).(3)

Destruction

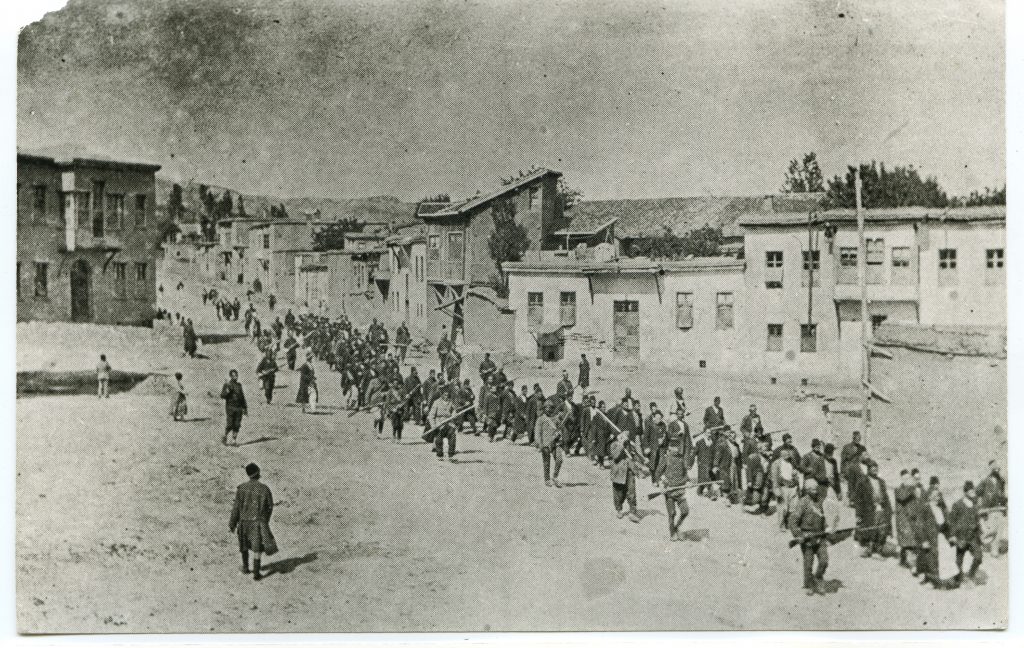

The first convoy, made up of Armenians from the three Mezre neighborhoods – Devriş, Nayil Beg and the markets – contained a total of 2,500 deportees; it set out on 1 July 1915. “The convoy was followed by a cart full of rope, which served its purpose shortly after the deportees left Mezreh, when the males were separated from the others and put under separate guard.”[4] After five weeks, they reached Deir ez-Zor via Arğana Maden, Diyarbekir, Mardin and Ras ul-Ayn, where only a handful arrived. All the others had been murdered on the way, had succumbed to exhaustion or – mostly young women and children – had been kidnapped by or sold to the local Muslim population.

Already the next day, 2 July 1915, a second convoy set out from Mezre, with roughly 3,000 deportees from the Karaçöl, Icadiye und Ambar neighborhoods, this time heading towards Malatya. “The deportees came from the most affluent families: the Fabrikatorians, Harputians, Kazanjians, Zarifians, Sarafians, Dingilians, Gurjians, Arparians, Totvians, Karaboghosians and Demirjians. Reverend Hovhan Sinapian was also in the convoy. The affluence of these Armenians doubtless explains why the caravan had a great many vehicles at its disposal and included many male family heads. It was not until Malatia that the men were separated from the others. We know nothing about how they died. The rest of the caravan continued on its way until Urfa. Some of those in it reached Der Zor several weeks later.”[5]

On 4 July 1915 the 4,500 Armenians of the large village of Hyuseinik were deported towards the direction of Malatya.

The inhabitants of the other Armenian villages of the Harput Plain were also deported in the course of July 1915, having suffered the conscription of men of draft age as well as arrests and the massacre of 3,000 labor soldiers in the months before. „(…) these 3,000 men were put on the road to Diyarbekir on 18 June and then slain in the defile of Deve Boynu or a place known as Güğen Boğazı, a few minutes distance from Maden. They were killed either by their own guards or by the çetes stationed there for the purpose.”[6]

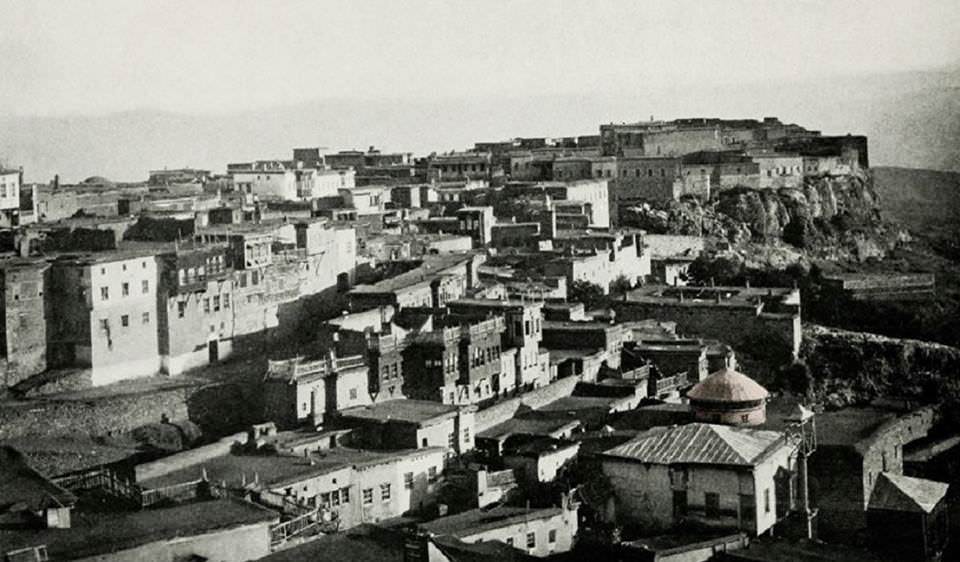

City of Kharberd / Harput

Harput (Armenian: Kharberd or Karberd; Syriac: Korberd) is located in the Harput plain, on the left bank of the Aradzan (Trk.: Murat; Eastern Euphrates) river. The lower stream of Aradzan is used as a waterway. In our time, Harput has preserved its role of a road junction.

The population of Harput was engaged in handicrafts, agriculture and trade. The Armenians were famous as skilled tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths, tinsmiths, linen makers, jewelers, tanners. At the end of the 19th century, they had established trade relations with Aleppo, Constantinople, Diyarbekir, Ayntap, Sivas, Malatya, Samsun, Tokat, Van, Adana, Arabkir, Palu, Bitlis and other places. The Gapamajian Trading Company of Van had a branch in Harput. There were about 100 shops in the city. In 1880-1890, Armenian merchants of Harput reached the foreign market: Russia, Iran, France, England, and even the US.

History

Harput’s settlement history dates back to the fourth millennium B.C. The oldest inhabitants were the Hurrians. The ancient tombs excavated in Harput date back to 20th – 18th B.C. centuries, when Hurrian tribes lived there. The Hurrians were soon replaced by the Hittites.

After the collapse of the Hittite Empire, Harput came under the rule of the Urartians. The fortress of Kharberd was first built by the Urartians in 9th – 8th B.C. centuries, then rebuilt in the 2nd century B.C. during the rule of the Armenian dynasty of Artashesians. The main wall was built with 1.5 m wide and 2 m high stone masses. The fortress had many rooms of different significance, and an underground road reached the nearby villages of Keorbe, Husenik and Mezre (also Mezire, Mezere(h)). In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Ottoman authorities used stones from the Kharberd Fortress to build a government building in Mezre.

Various empires and peoples settled in Harput over time, such as the Persians, the Romans, and the Byzantines. Built during the reign of Darius I (522-484 B.C.), the road connecting the Achaemenid capital Susa to the Mediterranean passed through the district of Harput, the historic Andzit.

Harput was developed as a military base during the second Byzantine occupation of the region, after 938. An imposing fortress was built on a wide rock outcropping overlooking the valley from the south. A town grew around the fortress, with a primarily Syriac and Armenian population that came from nearby villages as well as the city of Arsamosata further east. By the late 11th century, Harput had eclipsed Arsamosata to become the main settlement in the region. The commander of the Byzantine garrison in Harput was the distinguised general and warlord Pilartos Varajnuni (also Vahram Varajnuni; Grk.: Philaretos Brachamios; d. 1087) of Armenian descent. After the defeat of the Byzantines at the Battle of Manazkert (1071), the Armenian principalities of Kappadokia, Cilicia, Northern Syria, and Mesopotamia joined in one state, and Harput became its capital.

Around 1085, a Turkish warlord named Çubuk conquered Harput and was confirmed as its ruler by the Seljuk Sultan Malik-Shah I. The Great Mosque of Harput was built opposite the citadel by either Çubuk or his son (attested as the ruler here in 1107).

The first Artukid ruler of Harput was Balak, who was related to the Artukid rulers of Mardin and Hisn Kayfa, but not directly part of either ruling family. Balak died young in 1124, and the Artukids of Hisn Kayfa took over. Later, Imad ad-Din Abu Bakr, an Artukid prince who had previously attempted to usurp the throne of Hisn Kayfa, gained control of Harput. Harput remained an independent Artukid principality until 1234, when it was conquered by the Seljuks. It was during the Artukid period that the former population of Arsamosata became fully absorbed by Harput. In the early 1200s, one of the Artukid princes may have entirely rebuilt the citadel. In the subsequent period of Seljuk rule, not much was built in Harput.

In 1236 Harput was conquered by the Mongols. Since then, it has often passed from hand to hand. From the mid-14th century until 1433, Harput became part of the Beylik of Dulkadir. It was one of the main cities in this beylik, and the citadel was again rebuilt during this period. Under the Ottomans, Harput remained a prosperous industrial center, with thriving silk-weaving and carpet-making industries and many medreses.

Harput was also ruled by Timur Lenk (Tamerlane), the Kara Koyunlu (Qoyunlu), and Ak Koyunlu. The Ak Koyunlu ruled Harput from 1433-1478; the Ak Qoyunlu ruler Uzun Hasan‘s wife, a Greek Christian from Trebizond, lived here with her Greek entourage.

In 1507 Harput was invaded by Shah Ishmael I (also Ismail) of Persia, who plundered and destroyed the city. In 1515 it came under the rule of Ottoman Sultan Selim I. During Ottoman rule, the oppression of the native Christians intensified. The situation was especially aggravated at the end of the 16th century, when the productive forces were destroyed by the arbitrariness of the ruling elite, the violence of the Janissaries, and religious persecution. In search of a livelihood, most of its population emigrated to the western borders of the empire.

In 1617, Harput was completely destroyed and the inhabitants were massacred by Çobanoghli Bey.

Population

In the 18th century, when it belonged to the Sivas province, Harput became a crowded city again, mainly thanks to the Armenians of the surrounding provinces. In 1800 8,000 families lived there, in 1850 – 6,000 families.

Along with economic and cultural growth, the population of Harput, most of whom were Armenians, grew rapidly in the 1880s. Turks, Syriacs and Kurds also lived there. At the same time, the trans-Atlantic emigration of the people of Harput intensified, first to Canada, then to the USA. Emigration increased especially during the Hamidian massacres of 1895-1896. In 1914, Harput had a population of 18-20,000, with about 10,000 Armenians.

‘Provincial Athens’

Harput has been a famous center of Armenian culture and education. It is mentioned in a manuscript of 1160 that it was written “in the capital Harput”.

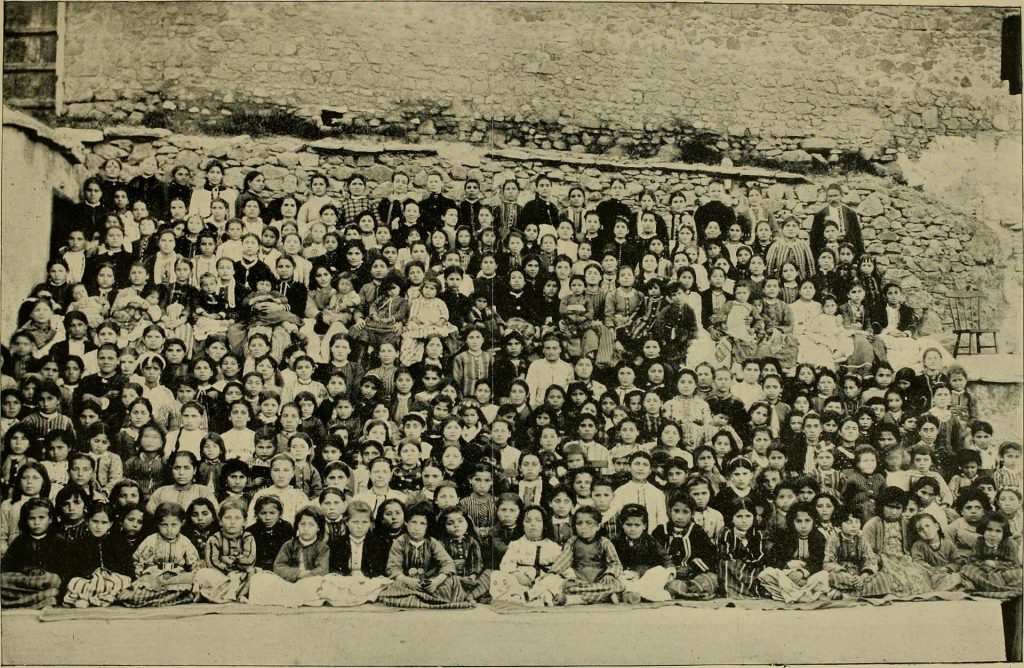

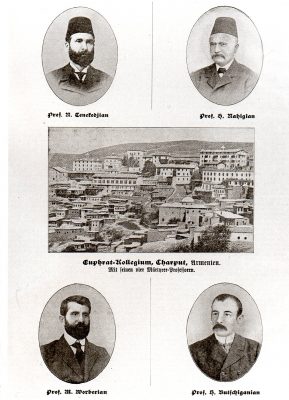

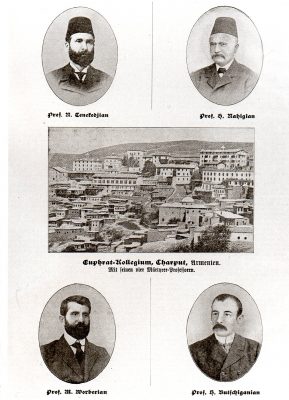

Among the prominent schools of Harput were Surp Hagop (Surb Hakob) Central School, Hripsimeants School for girls, the Smbatian Djemaran for boys and girls. Founded in 1892, the Mezire Central High School is the first modern school. French, German and American missionary institutions established three respectable colleges; of particular educational and cultural significance was the Armenia College, founded in 1878 and renamed Euphrates College in 1888 by the Turks. Euphrates College has produced more than 600 graduates. Thanks to this educational network, Harput was called the ‘provincial Athens’, and the advanced people of Harput reached high government positions.

The Theological Seminary, which operated from 1859 to 1915, enjoyed nation-wide fame. Armenian, classic Armenian (grabar), Armenian history, theology, anthropology, philosophy, and cosmology were taught here. Already in 1865, the educational and cultural Smbatian Society was organized, which founded the Smbatian Djemaran. The first theatre play, ‘Brave Vardan’, was staged in Harput in the 1880s. In 1889 Armenians established the printing business in Harput; since 1909 the ‘Euphrates’ newspaper was published. The Araks company expanded its activities among women.

Destruction

“The fate of a number of European-educated Armenian professors at the Missionary College in Harput, who had been serving for 15, 16, 25, 33 years, is shocking. Prof. N. Tenekedijan was thrown into prison, the hair of his head, mustache and chin was plucked out, then, after fasting day and night, he was hung up by his arms and beaten, deported on 20 June and murdered on the highway; Prof. H. Nahigian, deported on 5 June, was also murdered, and Prof. M. Vorberian witnessed the agony of a man who was beaten almost to death, and became insane as a result; after the deportation he was killed at the first stop. With him was killed his colleague Prof. H. Buchiganian, who had three fingernails torn out by the root, among other tortures. A Protestant clergyman, who two years before had warmly welcomed Dr. (Eduard) Graeter in Basle on his way through, also had his fingernails torn out.”

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 2. Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918

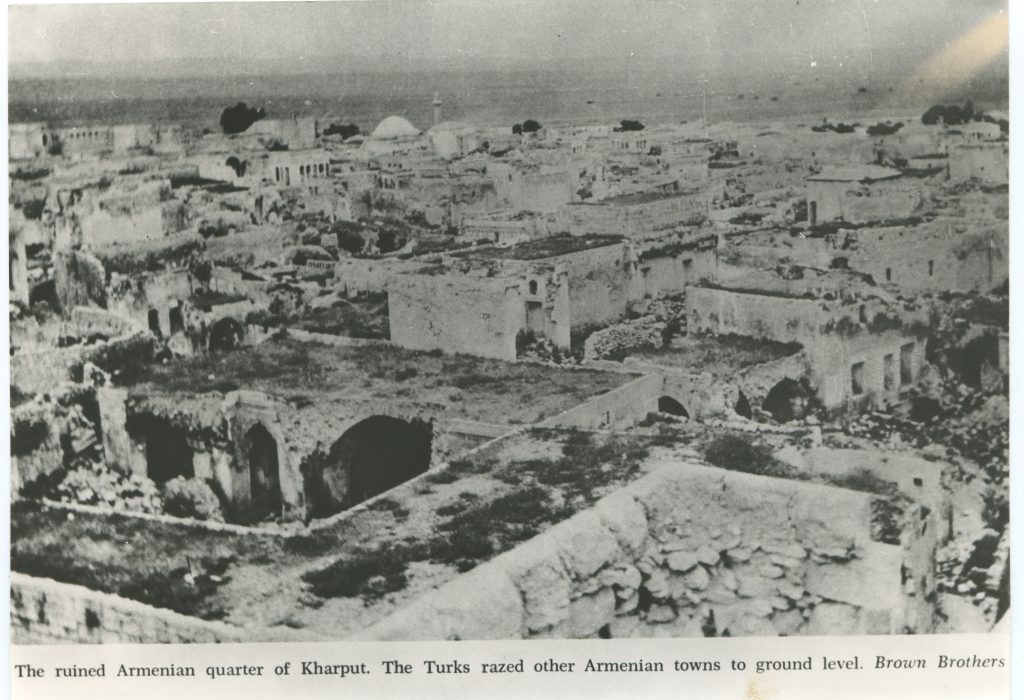

Beginning on 10 July 1915, the Armenian population of Harput was deported in several convoys. The first convoy included 150 families from the Vari Tagh (“Lower Quarter”) district and was guarded by Kurds and gendarmes. The former kaymakam of Harput, general practitioner Dr. Artin Bey Helvajian, was deported on 14 July 1915, along with several other leading personalities of the town, including the Catholic primate of the Harput diocese, Archbishop Stepan Israyelian, as well as Father Sarkis Khachaturian, Father Ghevont Minasian, and four nuns from the Order of the Immaculate Conception. With the exception of three women who managed to escape, all were massacred by the gendarmes the following day.

The third convoy from Harput consisted of about three thousand people and left for Malatya on 18 July. At dawn that day, the army surrounded the upper part of the city and expelled the Armenian population from their homes, with the exception of five Armenian artisan families and the Greeks and Syriacs. The men of the third convoy were separated from their families in Çiftlik, a three-hour walk from Malatya, locked up in nearby barracks and killed there. “In a 24 July report, Consul Davis indicates that 12,000-15,000 Armenians had already been deported from Mezreh and Harput by that date. Between 1,000 and 1,500 remained in the city with permission or through bribery or in hiding.”[7]

Among those remaining were the inmates of Mezre’s Central Prison, once the leading citizens of Harput, Mezre and Huseynik (Hyusnyak). When Dr. Nshan Nahigian refused to be deported to Urfa at night-time on 3/4 August, the prison was set on fire, and the political elite of Harput-Mezre died in the flames.[7]

Further Reading

Recollections of Khachadoor Pilibosian (born 1904, village of Ichme – 1989): They Called Me Mustafa. https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/ethnic-groups/armenians/they-called-me-mustafa/

Samuel Zurlinden: Massacres and Deportation from Harput

“From Harput the first transport left on the night of 23 June. There were several professors of the American College and other distinguished Armenians, as well as the prelate of the Armenian-Gregorian Church. They have disappeared. Now in Harput, too, the first batches of deportees were arriving from Erzincan and Erzurum, ragged, dirty, starving, sick. They had been on the road for two months, almost without food, without water. They were given hay, like animals; they were so starved that they threw themselves on it, but the zaptiyes drove them back with sticks and some were killed. On 6 July, 800 men from Harput had to leave the town. They were tied together in groups of fourteen (which was the length of the rope). The following day the convoy arrived in a secluded valley. The people were made to sit down and then fire was opened on them until no one moved. In a nearby village, another group was locked in the mosque and neighboring houses; they were left inside for three days without food or water, then led into a nearby valley, leaned against a rock wall and shot, the survivors massacred with bayonet and knife wounds. No charges were brought against any of them; nor was there even a semblance of a verdict. On 10 July, new massacre of several hundred at a distance of two hours from the city. The same executions in all Armenian villages in the area (…).”

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 2. Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1918

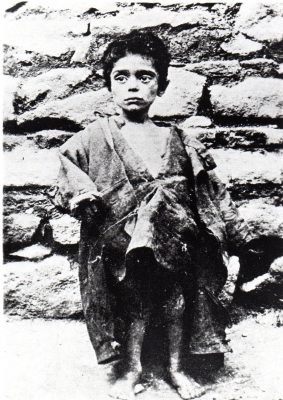

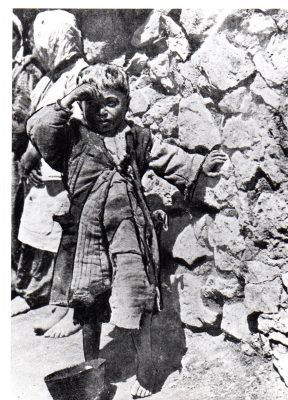

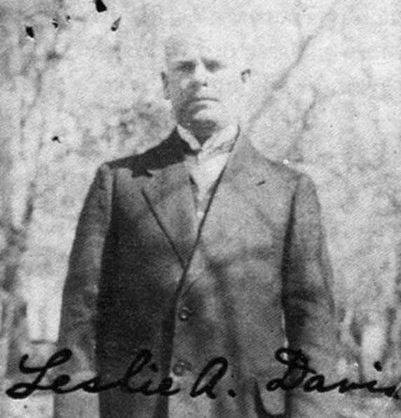

Leslie A. Davis: Armenian Deportees in Harput

«There were parties of exiles [deportees] arriving from time to time throughout the summer of 1915, some of them numbering several thousand. All of them were in rags and many of them were almost naked. They were emaciated, sick, diseased, filthy, covered with dirt and vermin, resembling animals far more than human beings. They had been driven along for many weeks like herds of cattle, with little to eat, and most of them had nothing except the rags on their backs. When the scant rations which the Government furnished were brought for distribution the guards were obliged to beat them back with clubs, so ravenous were they. There were few men among them, most of the men having been killed by the Kurds before their arrival at Harput. Many of the women and children also had been killed and very many others had died on the way from sickness and exhaustion. Of those who had starved, only a small portion were still alive and they were rapidly dying.

As one walked through the camp mothers held out their children, begging the visitor to take them and care for them or trying to sell them for a few piasters (a piaster is equivalent to about four cents). Many Turkish officers and other Turks visited the camps to select the prettiest girls and had their doctors present to examine them. I afterwards had occasion to try to help a little girl about twelve or thirteen years of age by the name of Siranous Hoghgroghian, who had come with a party from Erzincan. Her uncle in New York, Mr. Hrabad Hoghgroghian, sent a communication to me through the [State] Department and the Embassy, asking me to protect her and saying that he would send funds for her. After considerable search my cavasses found her living with a Turkish officer. She came to the Consulate and told me to inform her uncle that she was all right and needed no money. She was well developed for her age and was a comparatively good looking girl but was beginning to show the marks of the life that she was living. Young as she was, we noticed that she appeared to be pregnant and a month or two alter she did give birth to a child. I reported about her to her uncle in New York, but I think my report failed to reach him and perhaps it was just as well. This is only one of thousands of similar instances that occurred in a situation where no missionary or foreign official could do much to help these unfortunate people.”

Experted from: Davis, Leslie A.: The Slaughterhouse Province: An American Diplomat’s Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1915–1917, ed. by Susan X. Blair. New York, 1989, p. 75f.

Leslie A. Davis: Change of Population in the „Slaughterhouse Province” (Consular Dispatch of 30 December 1915)

Professor Laurence Howland MacDaniels. Papers 1915-1986. #21/25/815. Box 41)

“(…) The term of ‘Slaughterhouse Vilayet’ which I applied to this Vilayet in my last report upon this subject (that of September 7th) has been fully justified by what I have learned and actually seen since that time. It appears that all those in the parties mentioned on page 15 of that report, men, women and children, were massacred about five hours distance from here. In fact, it is almost certain that, with the exception of a very small number of those, who were deported during the first few days of July, all who have left here have been massacred before reaching the borders of the Vilayet. It is somewhat difficult to understand the plan by which people were brought all the way here from Trebizond, Urdu [Ordu], Kherassou [Giresun, Grk.: Kerasounta, Kerasous], Zara, Erzurum and Erzincan, only to be butchered in this Vilayet. During the second week of September several hundred Armenians who had been taken grain to Mush for the Government returned here with their ox-carts. Nearly all of them were then put in prison and a few days later were sent out and killed. During the last two months quite a number of Armenian soldiers have been brought back in group of two or three hundred from Erzurum. They have arrived in a most pitiable state due to their exposure on the way at this season of the year and the privations they had suffered.

Cornell University Archives, Professor Laurence Howland MacDaniels. Papers 1915-1986. #21/25/815. Box 41)

After all they had endured and after having been brought this far it appears that nearly all of them were killed a few hours after leaving here. A few have escaped and have related how the gendarmes tied them together a short distance out of town. The significance of that was apparent and some resisted. Their dead bodies may be seen alongside of the road. The rest of them are said to have been taken a little farther and killed in the mountains. One of the sad sights of this town now is to see companies of these soldiers being brought here every little while when we know that they are to be butchered like animals. We are all wondering why this Vilayet is chosen as the slaughterhouse.

A striking feature of the present situation in this vicinity is the large number of immigrants who have arrived from the direction of Van, Mush, and Bitlis. Many of the Armenian villages that were entirely depopulated during the summer are now filled with these Moslem immigrants. It is thought by some that one reason for destroying the Armenians was to make room for them. At any rate, there seems to be enough of them to fill the vacant places. As they appear to be a very poor class of people, it remains to be seen what the effect will be industrially of this change in the population of the region.”

Experted from: Davis, Leslie A.: The Slaughterhouse Province: An American Diplomat’s Report on the Armenian Genocide, 1915–1917, ed. by Susan X. Blair. New York, 1989, p.181f.

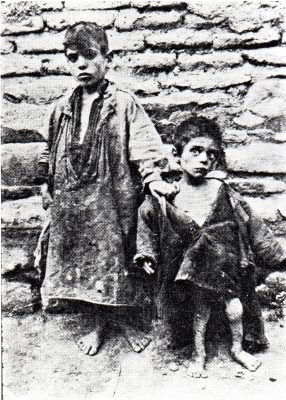

Burnt alive or drowned: The Plight of Armenian and Greek Orphans

1915

In the capital Mezre of the Central Anatolian province of Mamuret ül-Aziz there was a US consulate as well as orphanages and schools run by the German Hilfsbund für Christliches Liebeswerk im Orient and the American missions. This was the largest German mission run in the Ottoman Empire.[9] Hans Bauernfeind, brother-in-law of the missionary Ernst Christoffel and head of the Bethesda mission station in Malatya, noted in his diary on 31 July 1915 the refusal of the Hilfsbund station in Harput-Mezre run by Pastor Johannes Ehmann to host missionaries from the Bethesda station who were leaving Malatya via Mezre:

“(…) From Mezereh came the telegraphic answer to our Turkish letter: ‘Unfortunately I cannot receive you under these conditions.’ This means that the German orphanage in Mezereh will also not remain. (…) We immediately registered with the Mutessarif in order to discuss with him what was necessary (…). We showed him our telegram from Mezereh and asked for advice. He said, he would have known that beforehand, but he wouldn’t have wanted to keep us from asking ourselves. Since the strict order had been given not to leave a single Armenian in the six Vilayets in question, the orphanage in Mezereh could not stand still. Because if the government would not close the orphanages, if children under the age of 15 would be allowed to stay here, the Germans would be forced to close their own institutions, because all helpers would have to leave. (…)“[10]

From Bauernfeind’s diary entry it becomes apparent that in order to hinder foreign charitable activities, basically nothing more was necessary than to deport all Armenian employees and staff of the mission stations.

Pastor Johannes Ehmann as the director of the Mezre mission, on the other hand, telegraphed more optimistically to the German Embassy in Constantinople about the situation under 10 September 1915:

“Widows and orphans work with over 450 fosterlings has continued without serious disruption to date. All school buildings and an orphanage have been occupied by the military for six months and therefore school operations have been suspended. More than half of the teaching staff here; day students with families mostly accounted for. The reopening of our schools in the previous scope with Turkish and German teaching languages is desired.”[11]

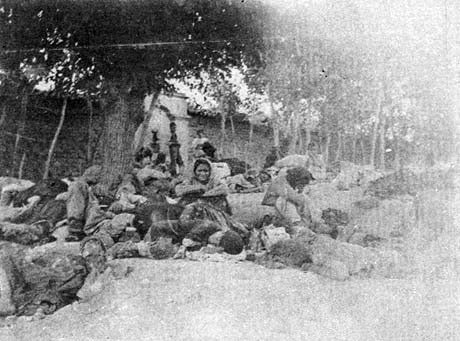

As a rule, Ottoman officials rejected offers of humanitarian aid from foreigners. Leslie Davis, in 1915 the only US consul remaining in the interior of Anatolia, asked the provincial governor for permission to open an orphanage in view of the numerous orphans in the deportee convoys. But Governor Sabit Cemal Sağiroğlu refused to do so on the grounds that the government wanted to take care of the Armenian orphans itself. Shortly afterwards Sabit ordered the deportation of the women and children first from Mezre and later from Harput as well. Consul Davis noted in his diary: “It is true that the Turkish government did establish some orphanages for the Armenian children and left them there for a short time. Then the children disappeared and it was reported that they had all been taken to a lake about twenty miles from Harput and drowned.”[12]

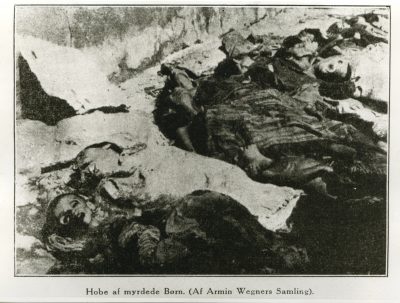

He found the rumor confirmed during a later exploratory trip to the crater lake Gölcük (today: Hazar Gölü), where he found the bodies of at least ten thousand Armenians, all with bayonet wounds in chest or stomach and mutilated. The shocked diplomate wrote: “That which took place around beautiful Lake Goeljuk in the summer of 1915 is almost inconceivable. Thousands and thousands of Armenians, mostly innocent and helpless women and children, were butchered on its shores and barbarously mutilated.”[13]

According to the French Armenian scholar Raymond Kévorkian, the orphans both in the German and the American orphanages of Mezre were exterminated either by drowning or burning them alive in late 1915:

“After the early November deportations of 1,000 Armenians who had been left in Mezre and Harput there remained only 150 girls in the custody of the American missionaries, 300 to 500 children in Mezre’s German orphanage (…).

With the departure of a number of American missionaries on 15 November, the authorities stepped up their harassment, demanding that the Americans hand over the girls in their institution. As for the wards of the German orphanage, its Danish director, Genny Jansen, informs us that, in January 1916, the authorities officially requested that Reverend Ehmann hand the children over to them, so that they could ‘be sent to the places where their parents are’. After obtaining ‘solemn assurances that these children would be delivered to their destination safe and sound’, the orphanage’s German staff entrusted the 300 boys to the ‘special agents’ come to take them away. Two days later, two of the orphans arrived at the German orphanage ‘covered with sweat from running so long’ and informed their former protectors that ‘their comrades [were] being burned alive’ at two hours’ distance from Mezre. Jansen confesses that she did not believe a word of this ‘very incredible story’ at first, but that, when she went the next day with the German nuns to the place that the orphans had described, she saw a ‘still smoldering heap’ and the ‘poor children’s charred skeletons.’ Inexorably, the authorities were eliminating the last traces of an Armenian presence in the region.”[14]

“The 500 boys between four and eight, who had been rounded up in the countryside or the city’s deserted neighborhoods in July after the deportation and placed in what the authorities called ‘orphanages’, had in fact been cramped into abandoned houses in Mezre and left without food and water. In three days, 200 of them perished. The missionaries (…) were not allowed to visit these ‘institutions’. The odor of the children’s rotting corpses led to protests from the Turkish population, which demanded that the authorities bring this experiment to an end. The surviving children were ultimately deported to the southwest on 22 October. Those who did not die on the road were thrown into the Euphrates at Izoli, a short distance from Malatya.”[15]

In 1917, the Swiss historian and journalist Samuel Zurlinden summarized the fate of the Armenian children in Harput as follows: “The Armenian children in the German orphanage in H… [Harput] were sent into exile with the rest. ‘My order,’ said the Vali, ‘is to expel all Armenians. I cannot make an exception with these.‘ Meanwhile, he announced that an orphanage would be set up by the government to take in all the children left behind, and soon after he approached Sister D. A. and asked her to visit this orphanage with him. The sister came with him and found about 700 Armenian children in a purpose-built building. Each twelve to fifteen children had an Armenian attendant, and they were well dressed and well fed. The Vali said, ‘See how the government cares for the Armenians,’ and she returned to the mission house, happily surprised; but when she paid a second visit to the orphanage a few days later, only thirteen of the 700 children remained; the others had disappeared. She heard that they had been taken to a lake [Gölcük Gölü, today Hazar Gölü] six hours away from the city and drowned there. Later, another 300 children who had recently been placed in the orphanage were taken away, and Sister D.A. believes that they met the same fate as the others. These were the last Armenian children in H. The most handsome boys and the prettiest girls had been picked out first, and the Turks and Kurds living in the vicinity had taken them away; the rest, which had remained in the hands of the government, were disposed of in this way.”

Excerpted and translated from: Zurlinden, Samuel: Der Weltkrieg. Vorläufige Orientierung von einem schweizerischen Standpunkt aus. Vol. 1.: Zürich: Art. Institut Orell Füssli, 1917

1917

The director of the German Hilfsbund mission, Friedrich Schuchardt, informed the German Foreign Office on 23 May 1917 about the situation of the orphanage in Mezre:

“To explain, we would like to point out that in Mamouret-ul-Aziz, among other things, we do a large orphanage work with over 600 children. Soon after Turkey entered the World War, the Turkish military authorities seized four houses, including a larger house that served as an orphanage, and in January of this year they demanded that all other houses be surrendered. After lengthy negotiations, the Turkish military authorities agreed to limit their demand to one more house, the inhabitants of which were accommodated in various smaller houses. The director of our work, Mr. Ehmann, the preacher, had sent two telegrams to the embassy on this matter, but apparently these telegrams were not promoted.

Since all the respected Armenians – and there were a large number of them in Mamouret-ul-Aziz – have been away from there for almost two years, it would have been easy for the military authorities to find suitable houses if they had shown some goodwill.

We therefore ask you to make an effort to ensure that the last house of our work that was taken down is returned and that the Turkish local command is satisfied with the four houses it already owns.”[16]

Schuchardt attached a letter from the wife of Pastor Johannes Ehmann, in which she reports on the return of Armenian women and children to the provincial capital:

“(…) Again, we have quite a lot of Armenians up here in the city, i.e. women and children; they come from all over the area around here, most of them had been with Turks for field work or as wives, and then were simply thrown out when they were no longer wanted. Some of them live here in the most miserable huts, in half-destroyed houses, because a large part of the Armenian houses was simply torn down by the population after the expulsion, first windows, doors, stairs etc. were dragged away, later the walls were torn down and all the wood that was inside torn out was used for burning. To this day, such wood is still brought from the villages for sale.”[17]

1922

As in other places, the Kemalist nationalists in Harput-Mezre also pursued a similarly restrictive policy towards foreign charities as their Young Turkish predecessors:

“In most locations, officials quickly drove deportees back onto the roads. Here and there NER [Near East Relief] orphanages were allowed to take in deportees; elsewhere, this was forbidden. At one point, NER in Harput was given an old German missionary building and allowed to take in a number of Greek children. ‘But in a very few days the building was empty,’ American Missionary Ethel Thompson reported. ‘The Turks had driven the children over the mountain.’ Ill- treatment of children was common. On February 5, 1922, Thompson ventured out on horseback to visit an outlying Christian orphanage. Five minutes outside of Mezre, she reached a watershed where some ‘300 small children who had been driven together in a circle’ were being ‘cruelly’ beaten by twenty gendarmes wielding heavy swords. When a mother rushed in to save a child, she was also beaten. ‘The children were cowering down or holding up their little arms to ward off the blows,’ Thompson reported. ‘We did not linger.’ She pointed out that the missionaries appealed to be allowed to take in Greek children whose mothers had died, but the missionaries were almost ‘always refused.’”[18]